Operative Management of Choledochal Cyst

Charles S. Cox Jr.

Robert Hetz

DEFINITION

Choledochal cyst represents a spectrum of cystic abnormalities of the extrahepatic biliary tree. It is not an isolated defect of the choledochus, rather, it also includes a constellation of abnormalities of the pancreaticobiliary system/junction.

The classification of the cystic structural abnormalities (types I to V) as originally described by Alonso-Lej1 and modified by Todani2 is typically used (FIG 1).

Type I is the predominant type of cyst (90% to 95% of cases) and is a fusiform, solitary dilation of the common bile duct (CBD) and hepatic duct. Type I is further subdivided into a, b, and c subtypes.

Type II is a cystic diverticulum of the CBD.

Type III (subtypes 1 and 2) is called a choledochocele and is a cystic dilation of the duct at the junction with the duodenum (intraduodenal subtype 1), with the CBD and pancreatic duct entering the intraduodenal choledochocele separately and draining into the duodenum via a stenotic/inflamed opening; and rarely, the intrapancreatic subtype 2, the choledochocele, is a diverticulum off the CBD at the level of the ampulla of Vater.

Type IV is a combined dilation of the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tree and is the second most common type of cyst.

Type V is also known as Caroli’s disease and is single or multiple intrahepatic cyst(s).

In terms of anatomy of the distal CBD, symptomatic infants often have a stenotic opening, and older patients have a patent communication. The types II, III, and V are all very rare, representing only a few percent of the total number of cysts.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of choledochal cyst is age-dependent.

In infants, the differential of most concern is cystic variants of biliary atresia; other abdominal cysts, including renal, are in the infant differential.

For older children, cystic lesions of the pancreas, hepatic tumors, rhabdomyosarcoma of the biliary tree, and cystic neuroblastoma are considerations. Most of these are distinguished on more advanced imaging, once the issue is raised with ultrasound.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with choledochal cysts are usually characterized as either infantile (now includes fetal or in utero diagnoses) or noninfantile forms.

Infantile (in utero): The infantile patient with an in utero diagnosis is an increasing cohort of patients; the cystic mass adjacent to the liver is usually noted on prenatal ultrasound in midgestation. There have been reports of cystic lesions visualized as early as 15 weeks, but most are in the 20 to 24 weeks of gestation range. The antenatal abnormality should be confirmed by ultrasound postnatally. The issue that arises is timing of surgical intervention, as even the infantile forms are often asymptomatic for months.

Infantile forms that are not in utero diagnoses are by definition symptomatic—abdominal pain/mass, jaundicemixed hyperbilirubinemia, acholic stools, and/or signs and symptoms of pancreatitis or cholangitis. In general terms, the infantile forms do not present with an abdominal mass or other signs of inflammation, rather, these patients are increasingly identified in utero with prenatal ultrasound and/or on postnatal ultrasound as part of the initial evaluation for mixed hyperbilirubinemia. Other presentations include failure to thrive and vomiting with mixed hyperbilirubinemia.

Noninfantile forms: Symptoms and signs of the noninfantile forms of choledochal cyst are classically described as right upper quadrant pain, jaundice (direct hyperbilirubinemia), and a mass. Pain and jaundice are the major symptoms, and it is rare that a right upper quadrant mass is palpable. The triad is present in fewer than 10% of patients. A bigger issue is the cause for delayed diagnosis/referral. The principal cause is either misdiagnosis of mixed hyperbilirubinemia as hepatitis and an incomplete evaluation of an episode of pancreatitis or hyperamylasemia with abdominal pain. Rarely, children can present with cyst rupture; there is no correlation between cyst size and risk of rupture.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Ultrasound is the initial imaging study of choice. Ultrasound is the least invasive and most cost-effective method of investigating the biliary tree after an episode of pancreatitis or abnormal elevations in liver enzymes in association with abdominal pain (with or without jaundice). This modality will suffice in the setting of calculus disease, but additional imaging with greater resolution is required when dilation of the biliary tree is identified.

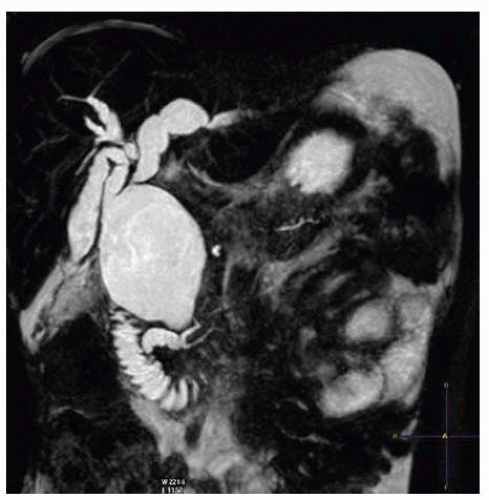

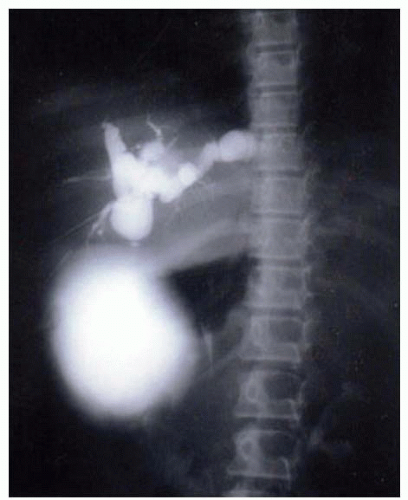

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) versus magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (FIGS 2 and 3): Both types of imaging of the biliary tree can be useful. ERCP was more frequently used in older children to obtain direct contrast injection into the extrahepatic biliary tree under fluoroscopic guidance. It provides excellent detail of the structural anatomy of the cyst but very

little input into the relationship to structures other than the pancreatic duct. ERCP has the advantage over MRCP in that it can also be therapeutic in the setting of obstructive jaundice. MRCP provides a similar level of detailed imaging of the ductal relationships with 3-D reconstruction of the anatomy of adjacent structures as well. MRCP also has the advantage of being noninvasive and thus is associated with less risk. FIG 4 shows an intraoperative cholangiogram of a type IV cyst that can be an adjunct to the other imaging modalities.

FIG 2 ERCP in an older child demonstrating a type I cyst with fusiform morphology and moderately dilated right and left hepatic ducts.

FIG 4 Intraoperative cholangiogram demonstrating a type IV cyst with multiple proximal ductal cysts that have areas of narrowing between the dilated regions (as opposed to the type I cyst).

Computed tomography (CT): CT imaging is most commonly used when investigating abdominal pain of an undetermined etiology and when the findings suggest a choledochal cyst. With the more advanced CT imaging and 3-D reconstruction /multiplanar imaging now available, MRCP or ERCP is rarely required if a CT has been obtained.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The technique described in the following text represents the principal management of types I and IV cysts, which represents over 95% of choledochal cyst cases. Timing of intervention: The debate surrounding immediate (first 2 weeks of life) versus delayed (6 weeks to 3 months of age) surgical intervention hinges on whether there is a risk for progressive liver dysfunction developing in the interim time of waiting. There are no solid data to support either approach. The rationale for not waiting indefinitely is due to the fact that it can be somewhat difficult to distinguish the cystic variant of biliary atresia from a choledochal cyst in infancy. Missing the window to surgically correct a patient with biliary atresia is a potentially devastating complication that is avoidable. A reasonable intermediate approach is to follow the asymptomatic, anicteric patient serially with serum biochemical studies and ultrasound with a planned operation at 6 weeks of age to earlier if worsening. Symptomatic patients or patients with a mixed hyperbilirubinemia undergo early operation if other comorbidities are manageable. Older patients can undergo operation when physiologically stable. If these patients present with cholangitis/pancreatitis, they can typically be managed akin to an adult with gallstone pancreatitis. Once the acute inflammatory response has subsided, an operation is performed during that admission, as early recurrent pancreatitis is the norm.

Preoperative Planning

We advise the use of an epidural catheter for perioperative pain management, and this is placed after the induction of anesthesia. Two peripheral intravenous lines, radial arterial line, Foley catheter, and nasogastric tubes are routinely inserted under aseptic conditions. Any coagulopathy is corrected preoperatively (unusual), and 20 mL/kg body weight of packed red blood cell (PRBC) are crossmatched and available for the procedure. Preoperative cefoxitin (40 mg/kg body weight) is used as antibiotic prophylaxis and redosed at 4 hours if needed.

Positioning

The patient is placed supine on the operating room table such that fluoroscopic cholangiography can be performed if needed. A small towel “bump” is placed under the right flank. The right arm is on an armboard at 90 degrees (FIG 5).