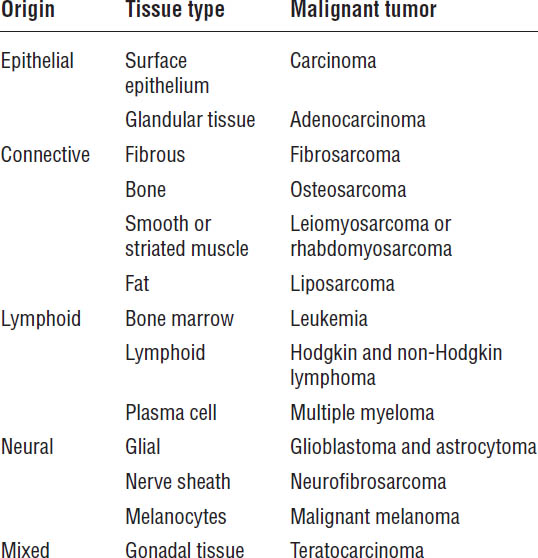

Table 23-1. Tissue Origin of Malignant Tumor Types

Adapted from Shord, Medina, 2014.

Clinical Presentation

The first signs and symptoms of cancer (solid tumors) develop when the tumor has grown to approximately 109 cells (1 cm in diameter or 1 g mass). The type of cancer determines the presentation of signs and symptoms, which vary widely across tumor types.

Positive screening tests (see Table 23-11 in Section 23-5) or generalized signs of anorexia, fatigue, fever, weight loss, and anemia must also be evaluated. Box 23-1 shows the American Cancer Society’s warning signs of cancer.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

The following factors promote cancer:

■ External factors: Tobacco, chemicals, radiation, infectious organisms, and diet

■ Internal factors: Genetics, hormones, and immune conditions

Development of cancer is genetically regulated and is a multistage process:

■ Initiation: Normal cells are exposed to chemical, physical, or biological carcinogens. Such exposure results in irreversible damage, genetic mutations, and selective growth advantages.

Box 23-1. Warning Signs of Cancer

Unexplained weight loss

Fever

Fatigue

Pain

Skin changes

Change in bowel habits or bladder function

Sores that do not heal

White patches inside the mouth or white spots on the tongue

Unusual bleeding or discharge

Thickening or lump in the breast or other parts of the body

Indigestion or trouble swallowing

Recent change in a wart or mole or any new skin change

Nagging cough or hoarseness

American Cancer Society, 2014

■ Promotion: Reversible environmental changes favor the growth of the mutated cells.

■ Transformation: The cells become cancerous.

■ Progression: Additional genetic changes occur, resulting in increased cancerous proliferation. Tumors invade local tissues, and metastasis occurs.

Genetic alterations are necessary for the development and growth of cancer. Some of the most common are the following:

■ Oncogenes promote growth advantages in mutated cells and cause excessive proliferation (e.g., ras, c-myc).

■ Inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) results in inappropriate cell growth, because TSGs normally regulate the cell cycle (e.g., p53).

• Anti-apoptotic genes are activated (e.g., bcl-2).

• DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) repair genes experience reduced activity.

Malignant tumor cells do not resemble their tissue of origin (in contrast to benign tumors). They are unstable and are incapable of performing normal cell functions.

Diagnostic Criteria

A sample of suspected malignant tissues or cells is needed for a definitive diagnosis. Sampling can be done with a biopsy, fine-needle aspiration, or exfoliative cytology. This tissue sample is examined by a pathologist, who assigns a stage to the cancer. This process is called pathological staging.

Radiation or chemotherapy should not begin without proper clinical and pathological staging. Clinical staging can be accomplished by imaging studies, which may include x-rays, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and bone scans. Laboratory work may include complete blood counts (CBCs), blood chemistries, and tumor markers.

If a diagnosis of cancer is made, the malignancy will need to be staged or categorized on the basis of severity of the disease and the results of the pathological staging tests. Staging guides the oncology practitioner in determining the prognosis and the treatment regimen for the patient.

The tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system is the most commonly used tool for solid tumors. Tumors are scored numerically on the basis of the size of the tumor, the extent of lymph node involvement, and the presence or absence of metastases. This score allows classification of tumors by stage, from 0 to IV, with stage IV denoting the presence of metastasis (e.g., most severe disease). A stage 0 tumor is called a carcinoma in situ, where the malignancy has not yet invaded the basement membrane of the epithelial surface.

Lymphoid tumors are staged differently and are beyond the scope of this review. Refer to Chan and Yee (2014) for more information.

Treatment Principles and Goals

Treatment regimens are based on the type of cancer, stage, age of the patient, and other prognostic factors (e.g., presence of a tumor marker, poor performance status, and ethnicity, among others).

Primary therapy is the initial and mainstay approach to treat cancer. It usually consists of removal of the tumor or debulking through surgery but may also include chemotherapy, radiation, or both.

Neoadjuvant therapy is given prior to the primary therapy. The goal is to reduce the size of the tumor, thereby increasing the efficacy of the primary treatment. Examples include chemotherapy or radiation.

Adjuvant therapy is additional therapy given after the main treatment, which is usually surgery. The goal is to ensure that all the residual disease has been eradicated. Adjuvant therapy usually consists of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both.

The four main cancer treatments are surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and biologic therapy. Most regimens are a combination of these modalities:

■ Surgery alone is reserved for solid localized tumors, where the entire cancer can be resected. It may also be combined with other modalities in later stages of the disease. It is not an option for patients with lymphoid-based disease (e.g., Hodgkin lymphoma).

■ Radiation alone is also reserved for curing localized tumors because it treats a very focused area. It also can be combined with other treatments as neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy to reduce disease-related symptoms or to reduce the incidence of disease recurrence.

■ Chemotherapy is a means of systemic treatment, in contrast to the two types of local treatment just described. It can be used to treat the primary tumor as well as metastases. Chemotherapy is generally not administered to patients with local disease that can be fully resected.

■ Biologic therapy is another systemic treatment and includes agents such as monoclonal antibodies, interferons, interleukins, and tumor vaccines. It is a relatively new type of treatment and acts by stimulating the host immune system.

The goals of cancer therapy are based on the type and stage of cancer, as well as on patient characteristics (e.g., an older patient with a short life expectancy may not be offered intense treatment that may impair quality of life). Goals may be as follows:

■ Localized or regional disease (i.e., stages 0, I, II, and early III): Provide curative intent, and inhibit recurrence of disease. Stage 0 diseases are often not treated but monitored until clinically apparent.

■ Advanced or metastasized disease (i.e., advanced stage III and all stage IV): Palliate symptoms, reduce tumor load, prolong survival, and increase quality of life.

Survival and response to treatment

In 2014, more than 1,600 people per day in the United States will die of a cancer-related cause, which accounts for about one in four deaths. Survival depends on patient characteristics, type of disease, stage of disease, and treatment regimen. Older patients with more severe disease, poor performance status, and faster-growing tumors have a poor prognosis.

Responses to treatment modalities for solid tumors are classified as follows:

■ Cure: 5 years of cancer-free survival for most tumor types

■ Complete response: Absence of all neoplastic disease for a minimum of 1 month after cessation of treatment

■ Partial response: ≥ 50% decrease in tumor size or other disease markers for a minimum of 1 month

■ Stable disease: No change or no meeting of criteria for partial response or progression

■ Progression: ≥ 25% increase in tumor size or new lesion

Response to treatment for hematologic cancers is measured by the elimination of abnormal cells, a decrease in tumor markers to normal, and the improved function of affected cells.

23-4. Drug Therapy

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapeutic agents have a very narrow therapeutic index and a toxic side-effect profile. They are generally more effective in combination because of synergism through biochemical interactions. It is important to choose drugs with different mechanisms of action, resistance, and toxicity profiles to get the full benefit of combination therapy.

Chemotherapy has the greatest effect on rapidly dividing cells, because most of the potent chemotherapy drugs act by damaging DNA. These agents are more active in different phases of the cell cycle. A therapeutic effect is seen on cancer cells, but adverse effects are also seen on human cells that rapidly divide (e.g., hair follicles, gastrointestinal [GI] tract, and blood cells). Agents can be phase specific or phase nonspecific. Nonspecific agents are effective in all phases.

Cell Cycle Phases

■ G0 = resting phase: No cell division occurs, and cancer cells are generally not susceptible to chemotherapy. This lack of susceptibility is problematic for slow-growing tumors that exist primarily in this phase.

■ G1 = postmitotic phase: Enzymes for DNA synthesis are manufactured, lasting 18–30 hours.

■ S = DNA synthesis phase: DNA separation and replication occur, lasting 16–20 hours.

■ G2 = premitotic phase: Specialized proteins and RNA (ribonucleic acid) are made, lasting 2–10 hours.

■ M = mitosis: Actual cell division occurs, lasting 30–60 minutes.

Drug Classes

There are numerous chemotherapy agents. Drugs are grouped by class. Refer to the corresponding table for each class of drugs.

Alkylating agents

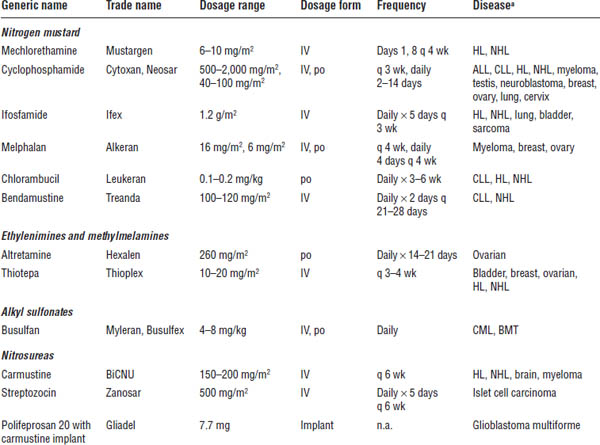

Table 23-2 provides summary information about alkylating agents.

Mechanism of action

Alkylating agents cause covalent bond formation of drugs to nucleic acids and proteins, which results in the cross-linking of one or two DNA strands and inhibition of DNA replication. These agents are not phase specific. The most commonly used agents include cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, carmustine, dacarbazine, and temozolomide.

Patient instructions and counseling

■ All drugs are carcinogenic, teratogenic, and mutagenic.

■ Medications may cause sterility.

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; BMT, bone marrow transplant; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; n.a., not applicable; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

a. Appearance of a disease in the list does not indicate U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the drug’s use in treatment of that disease, but does indicate use of that drug in that disease in clinical practice.

■ Let your dentist know you are on chemotherapy because of an increased risk of bleeding and infections.

■ Hydration and mesna therapy are recommended for cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide.

■ Let your health care provider know if you have burning when urinating.

Adverse drug events

The following adverse events may occur: myelosuppression, primarily leukopenia; mucosal ulceration; pulmonary fibrosis (carmustine) and interstitial pneumonitis; pyrexia and fatigue (bendamustine); alopecia; nausea and vomiting; amenorrhea and azoospermia; hemorrhagic cystitis (cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide); encephalopathy (ifosfamide); and seizures (polifeprosan and carmustine).

Drug interactions

Drugs with specific interactions of moderate to major severity include the following:

■ Altretamine: Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors

■ Bendamustine: Strong cytochrome P450 (CYP450) 1A2 inhibitors

■ Busulfan: Itraconazole, phenytoin, and acetaminophen

■ Carmustine: Cimetidine, ethyl alcohol, phenytoin, and amphotericin B

■ Cyclophosphamide: Allopurinol, barbiturates, digoxin, phenytoin, and warfarin

■ Ifosfamide: Allopurinol, phenytoin, and warfarin

■ Streptozocin: Nephrotoxic agents

Monitoring parameters

Monitor pulmonary function tests, renal and hepatic tests, chest x-rays, CBC with differential (baseline and expected nadir prior to next cycle) and electrolytes, urinalysis for red blood count detection from hemorrhagic cystitis, signs of bleeding (bruising and melena), infection (sore throat and fever), and nausea or vomiting.

Antimetabolites: S-phase specific

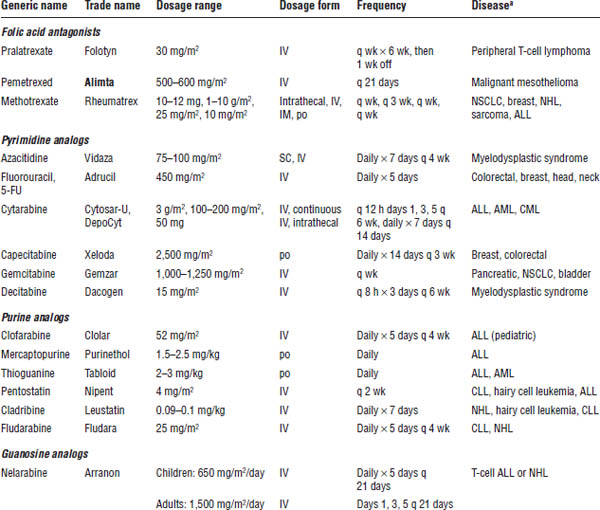

See Table 23-3 for general information about antimetabolites.

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer.

Boldface indicates one of top 100 drugs for 2012 by units sold at retail outlets, www.drugs.com/stats/top100/2012/units.

a. Appearance of a disease in the list does not indicate U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the drug’s use in treatment of that disease, but does indicate use of that drug in that disease in clinical practice.

Mechanism of action

These agents are structural analogues of natural metabolites and act by falsely inserting themselves in place of a pyrimidine or purine ring, causing interference in nucleic acid synthesis. Phase-specific agents are most active in the S phase and in tumors with a high growth fraction. They are subdivided into three groups: folate, purine, and pyrimidine antagonists.

Patient instructions and counseling

■ Avoid crowds and sick people.

■ If receiving fluorouracil (5-FU), you may be asked to chew ice to reduce damage to the mucosal lining in your mouth.

■ Contact your health care provider if you have uncontrollable nausea or vomiting; excessive diarrhea; or pain, swelling, or tingling in palms of hands and soles of feet (hand-foot syndrome).

■ Call your health care provider if you feel dizzy or lightheaded or have trouble urinating (clofarabine).

■ You should be receiving folic acid and vitamin B12 injections if you are receiving pemetrexed.

■ Nelarabine may cause sleepiness and dizziness.

Adverse drug events

Adverse events include hand-foot syndrome and stomatitis (5-FU and capecitabine); severe diarrhea, GI mucosal damage, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, myelosuppression, alopecia, and neurotoxicity (nelarabine, cytarabine, fludarabine, and methotrexate); rash, fever, and flu-like symptoms (gemcitabine); renal toxicity and mucositis (5-FU and methotrexate); conjunctivitis (cytarabine, especially in high doses); hemolytic uremic syndrome (gemcitabine); opportunistic infections (cladribine and fludarabine); and tumor lysis syndrome, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or capillary leak (clofarabine).

Drug interactions

Drugs with specific interactions include the following:

■ Capecitabine: Warfarin and phenytoin

■ Cytarabine: Digoxin

■ Fluorouracil: Warfarin

■ Mercaptopurine: Warfarin and allopurinol

■ Methotrexate: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), amiodarone, amoxicillin, sulfasalazine, doxycycline, erythromycin, hydrochlorothiazide, mercaptopurine, omeprazole, phenytoin, and folic acid

■ Pentostatin: Cyclophosphamide and fludarabine

Monitoring parameters

Note any complaints of mucositis or mouth soreness; monitor for neurotoxicity (e.g., ask the patient to write his or her name), CBC with differential prior to each dose of drug, and hepatic and renal function; and monitor for tingling or swelling of palms of hands and soles of feet, bruising or bleeding, and international normalized ratio (capecitabine). Monitor weight, and question patient about diarrhea, jaundice, and hepatomegaly (mercaptopurine). Continuous intravenous (IV) fluids and allopurinol for prevention of tumor lysis syndrome should be administered to patients taking clofarabine, and those patients should also receive prophylactic corticosteroids for systemic inflammatory response syndrome and capillary leak. Pemetrexed toxicities are reduced by lowering plasma homocysteine levels with concomitant folic acid and vitamin B12. Dexamethasone should be given to prevent cutaneous reactions caused by pemetrexed.

Antitumor antibiotics

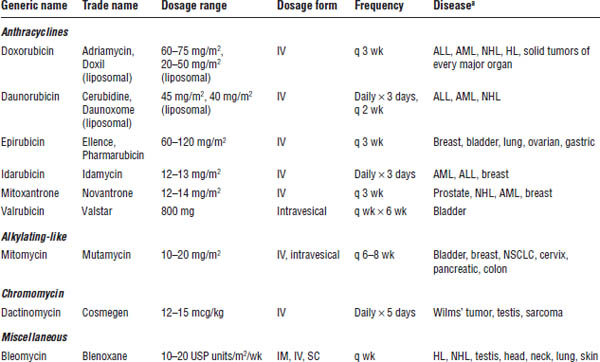

For additional information about antitumor antibiotics, consult Table 23-4.

Mechanism of action

Anthracyclines block DNA and RNA transcription through the intercalation (insertion) of adjoining nucleic acid pairs in DNA, which results in DNA strand breakage. They also inhibit the topoisomerase II enzyme. Mitomycin is an alkylating-like agent that cross-links DNA. Dactinomycin blocks RNA synthesis. Bleomycin inhibits DNA synthesis in mitosis and G2 stages of growth. Bleomycin is the only cell cycle–specific agent.

Patient instructions and counseling

■ Contact your health care provider if you have fast, slow, or irregular heartbeats or breathing difficulties.

■ Anthracyclines may cause a change of urine color or change the whites of eyes to a blue-green or orange-red color.

■ Bleomycin may cause a change in skin color or nail growth.

Adverse drug events

Events include severe nausea and vomiting, alopecia, and stomatitis. Anthracyclines may cause cardiac toxicity, acute or chronic (doxorubicin = daunorubicin > idarubicin > epirubicin > mitoxantrone). All anthracyclines have limits on cumulative lifetime dosing, are vesicants, and are associated with secondary acute myelogenous leukemia (AML); avoid in patients with a cardiac history. Myelosuppression risk exists with all agents, although mitomycin demonstrates a delayed effect. Dactinomycin may cause renal toxicity, leukopenia, and increased pigmentation of previously radiated skin. Bleomycin may cause pulmonary fibrosis and interstitial pneumonitis. Mitomycin may cause hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Table 23-4. Antitumor Antibiotics

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer.

a. Appearance of a disease in the list does not indicate U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the drug’s use in treatment of that disease, but does indicate use of that drug in that disease in clinical practice.

Drug interactions

Drugs with specific interactions include the following:

■ Bleomycin: Phenytoin and digoxin

■ Doxorubicin: Cisplatin, digoxin, paclitaxel, phenytoin, phenobarbital, trastuzumab, and zidovudine

■ Epirubicin: Cimetidine and trastuzumab

■ Idarubicin: Probenecid and trastuzumab

Monitoring parameters

Monitor hepatic and renal function, CBC with differential, and pulmonary function tests before and after treatment with bleomycin. Provide cardiac monitoring through left ventricular ejection fraction measurements for anthracyclines as well as monitoring of the cumulative lifetime dose, and be alert for extravasation and necrosis with anthracyclines. Adjust anthracycline dosing on the basis of elevated total bilirubin.

Pharmacokinetics

Anthracyclines are extensively bound in the tissue, have large volumes of distribution and long half-lives, and are excreted in the bile. Dosing adjustments are necessary in patients with hepatic impairment. Bleomycin is renally excreted and requires dosing adjustments in impaired patients.

Other factors

Lifetime doses of doxorubicin should not exceed 450–550 mg/m2, taking into account other anthracycline agents received. The lifetime maximum for epirubicin is 900 mg/m2; for idarubicin, it is 150 mg/m2.

Hormones and antagonists

Table 23-5 provides information about hormones and antagonists.

Mechanism of action

This diverse group of compounds acts on hormone-dependent tumors by inhibiting or decreasing the production of the disease-causing hormone.

Patient instructions and counseling

■ Avoid use in pregnant women; several agents may cause weight gain and menstrual irregularities in women.

■ Be aware of leg swelling or tenderness (e.g., signs of a deep-vein thrombosis), breathing problems, and sweating.

■ Transient muscle or bone pain, problems urinating, and spinal cord compression may occur initially in patients receiving luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists.

■ Take exemestane after meals.

Adverse drug events

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree