Transcription

Transcription of protein-coding genes by RNA polymerase II (one of several classes of RNA polymerases) is initiated at the transcriptional start site, the point in the 5′ UTR that corresponds to the 5′ end of the final RNA product (see Figs. 3-4 and 3-5). Synthesis of the primary RNA transcript proceeds in a 5′ to 3′ direction, whereas the strand of the gene that is transcribed and that serves as the template for RNA synthesis is actually read in a 3′ to 5′ direction with respect to the direction of the deoxyribose phosphodiester backbone (see Fig. 2-3). Because the RNA synthesized corresponds both in polarity and in base sequence (substituting U for T) to the 5′ to 3′ strand of DNA, this 5′ to 3′ strand of nontranscribed DNA is sometimes called the coding, or sense, DNA strand. The 3′ to 5′ strand of DNA that is used as a template for transcription is then referred to as the noncoding, or antisense, strand. Transcription continues through both intronic and exonic portions of the gene, beyond the position on the chromosome that eventually corresponds to the 3′ end of the mature mRNA. Whether transcription ends at a predetermined 3′ termination point is unknown.

The primary RNA transcript is processed by addition of a chemical “cap” structure to the 5′ end of the RNA and cleavage of the 3′ end at a specific point downstream from the end of the coding information. This cleavage is followed by addition of a polyA tail to the 3′ end of the RNA; the polyA tail appears to increase the stability of the resulting polyadenylated RNA. The location of the polyadenylation point is specified in part by the sequence AAUAAA (or a variant of this), usually found in the 3′ untranslated portion of the RNA transcript. All of these post-transcriptional modifications take place in the nucleus, as does the process of RNA splicing. The fully processed RNA, now called mRNA, is then transported to the cytoplasm, where translation takes place (see Fig. 3-5).

Translation and the Genetic Code

In the cytoplasm, mRNA is translated into protein by the action of a variety of short RNA adaptor molecules, the tRNAs, each specific for a particular amino acid. These remarkable molecules, each only 70 to 100 nucleotides long, have the job of bringing the correct amino acids into position along the mRNA template, to be added to the growing polypeptide chain. Protein synthesis occurs on ribosomes, macromolecular complexes made up of rRNA (encoded by the 18S and 28S rRNA genes), and several dozen ribosomal proteins (see Fig. 3-5).

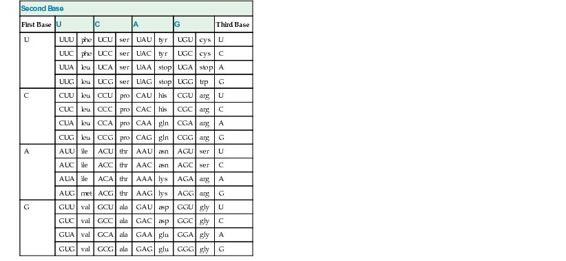

The key to translation is a code that relates specific amino acids to combinations of three adjacent bases along the mRNA. Each set of three bases constitutes a codon, specific for a particular amino acid (Table 3-1). In theory, almost infinite variations are possible in the arrangement of the bases along a polynucleotide chain. At any one position, there are four possibilities (A, T, C, or G); thus, for three bases, there are 43, or 64, possible triplet combinations. These 64 codons constitute the genetic code.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree