Chapter 32 Oesophagus, stomach and duodenum

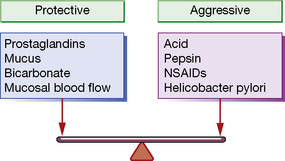

Gastric acid secretion and mucosal protection

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori): an occasionally silent killer

It is now known that a large majority of benign gastric and duodenal ulceration is due to H. pylori infection (following Marshall and Warren’s Nobel prize-winning experiments1,2); most of the remainder can be attributed to NSAID use. Colonisation of the stomach with H. pylori is seen in virtually all patients with a duodenal ulcer and in 70–80% of those with gastric ulcers. H. pylori appears to stimulate increased acid secretion. All patients colonised with H. pylori develop gastritis, but only about 20% have ulcers or other lesions. As yet incompletely understood host factors and differences in strain of the organism are likely to explain this discrepancy.

NSAIDs: enemies of the gut

Aspirin and the other NSAIDs inhibit cyclo-oxygenase (COX) (see Ch. 16). In the stomach, the constitutively expressed COX-1 isoform is responsible for the production of the gastroprotective prostaglandins E2 and I2 (see above). Inhibition of the inducible COX-2 isoform (which is normally up-regulated in activated inflammatory cells) is responsible for NSAIDs’ anti-inflammatory properties. Most NSAIDs inhibit both isoforms unselectively, so the beneficial anti-inflammatory effect is offset by the potential for mucosal injury by depletion of protective prostaglandins. Aspirin is particularly potent in this respect, perhaps because it inhibits COX irreversibly, unlike the other NSAIDs where inhibition is reversible and concentration dependent.

Drugs affecting oesophageal motility and the lower oesophageal sphincter

Newer therapies being explored in the treatment of GORD include GABA inhibition to reduce transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations. Baclofen (see p. 304) is clinically effective but has limiting CNS unwanted effects, and more tolerable compounds are being investigated. Other pharmacological targets which are showing potential in early clinical research include cannabinoid agonists.

Drugs to reduce or neutralise gastric acid

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

Pharmacology

As can be deduced from the above, the most effective site of action for antisecretory drugs is the proton pump. Proton pump inhibitors are taken up by parietal cells from the portal circulation and are then excreted into the acid milieu around the secretory canaliculus. The resulting ionised form binds irreversibly to the proton pump, resulting in virtual total inhibition of acid secretion (Fig 32.1).