(1)

Department of Pathology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Keywords

JawNeoplasmsOdontogenic tumors6.1 Introduction

Both odontogenic epithelium as well as odontogenic mesenchyme may show malignant neoplastic degeneration, causing either odontogenic carcinomas or odontogenic sarcomas [1–3]. With the exception of the malignant ameloblastoma, all entities to be mentioned show the clinical presentation and course as well as the radiographic appearance of an intraosseous malignant tumor.

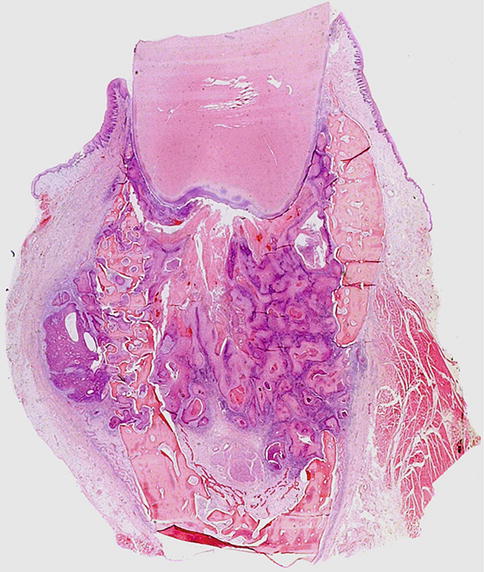

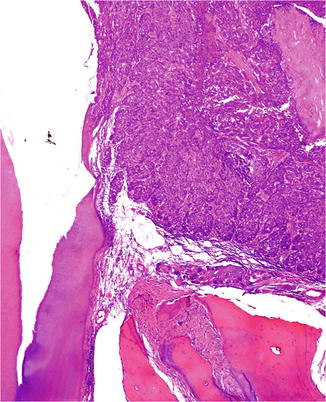

6.2 Malignant Ameloblastoma

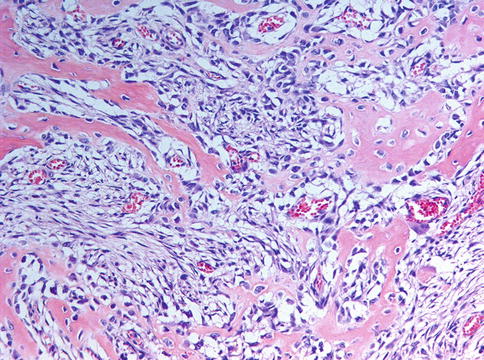

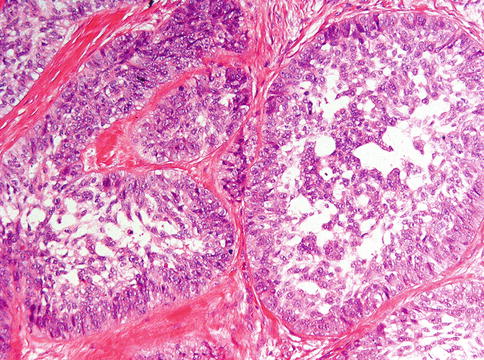

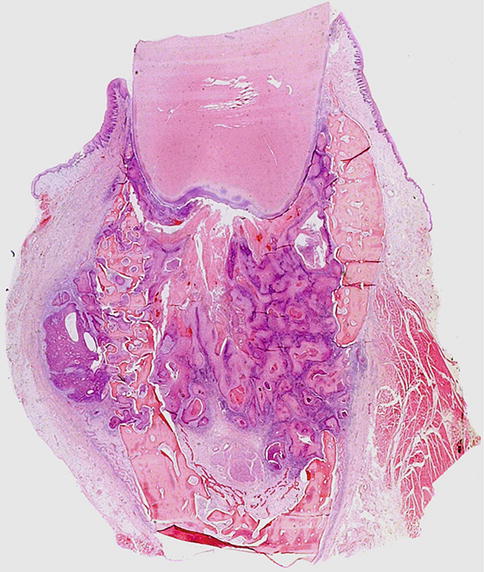

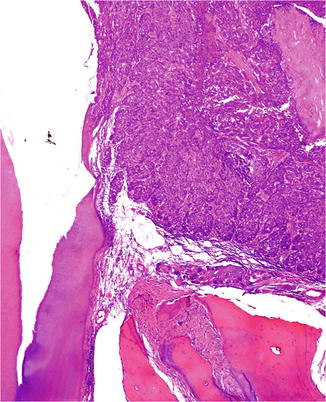

Malignant (metastasising) ameloblastoma is an ameloblastoma that metastasizes in spite of an innocuous histologic appearance. The primary tumor does not show any specific features different from conventional ameloblastomas that could predict metastatic potential (Fig. 6.1) [4–6].

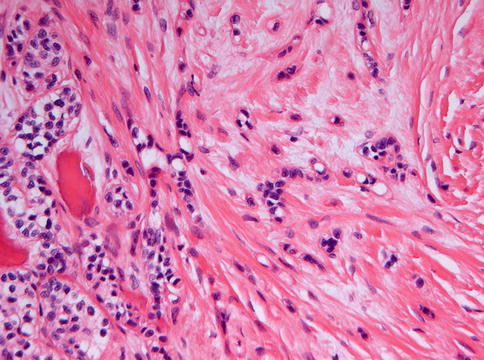

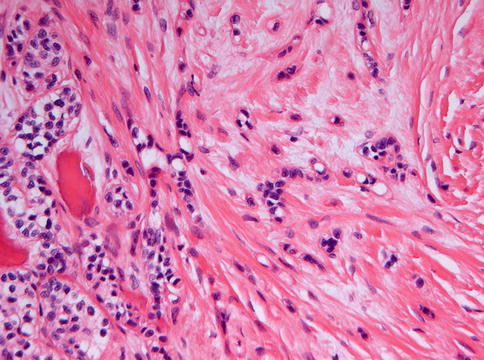

Fig. 6.1

Ameloblastoma metastatic to the liver

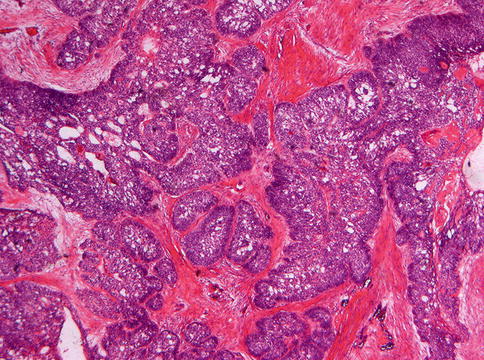

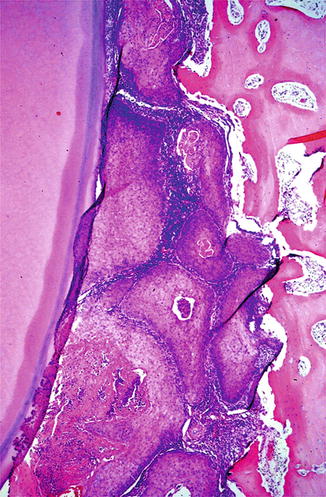

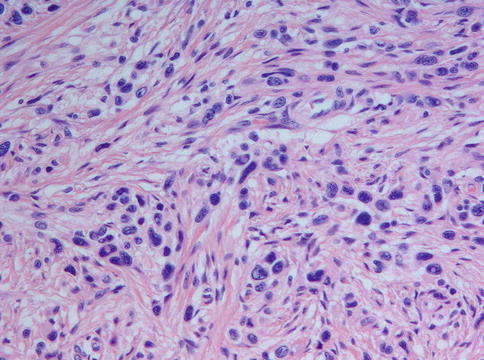

6.3 Ameloblastic Carcinoma

Ameloblastic carcinoma shows combined histologic features of both ameloblastoma and squamous cell carcinoma [1, 8]. Most cases occur in the mandible as asymptomatic swellings and, radiographically, perforation of the cortical bone plate and extension into the adjacent soft tissues are non uncommon and may lead to the suspicion of a malignant lesion.

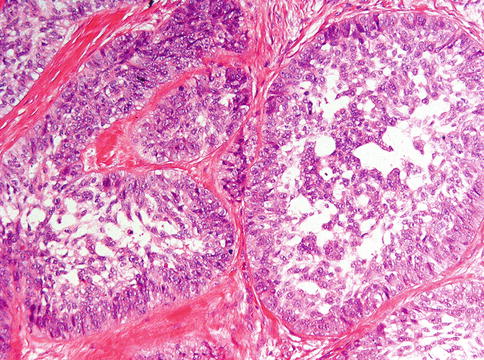

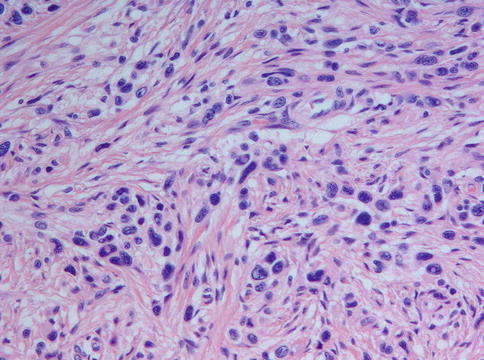

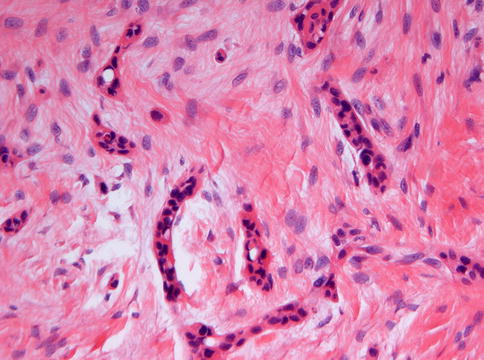

The tumor resembles ameloblastoma by the presence of epithelial islands with peripheral columnar cells that show palisading at the border with the stroma but also exhibits pronounced cytological atypia and mitotic activity, thus allowing the separation from ameloblastoma (Figs. 6.2 and 6.3).

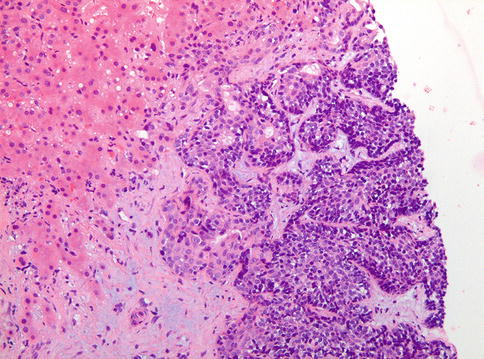

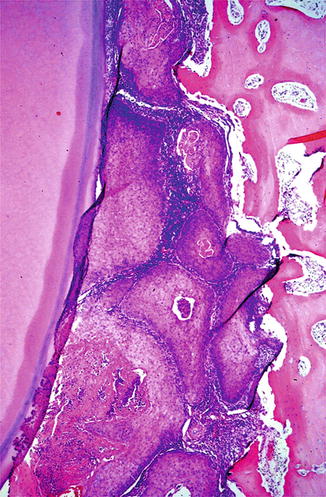

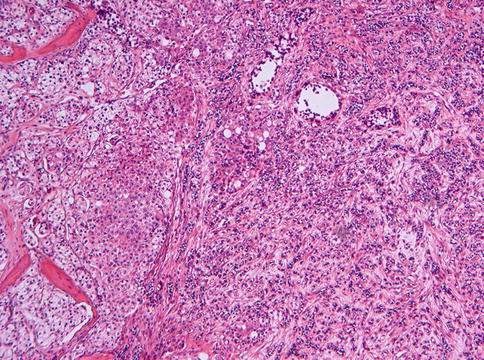

Fig. 6.2

Low power view of ameloblastic carcinoma to show the architecture of an ameloblastoma with peripheral columnar cells and more loosely arranged spindle cells centrally

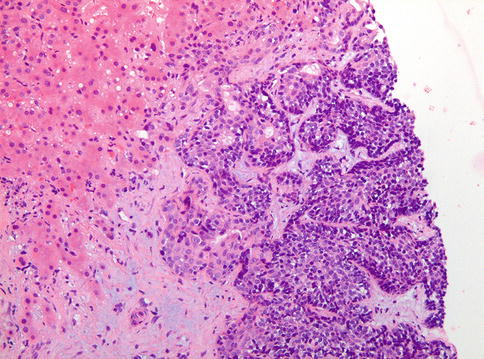

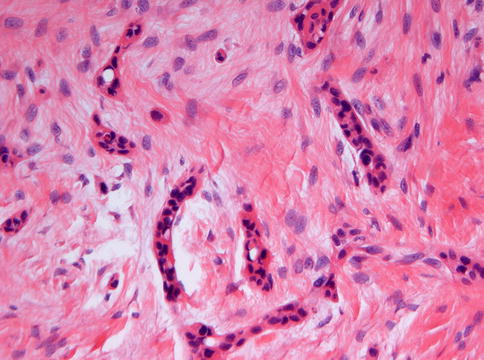

Fig. 6.3

At higher magnification, it is seen that ameloblastic carcinoma shows cytonuclear atypia and mitotic activity

6.4 Primary Intraosseous Carcinoma

Primary intraosseous carcinoma is a squamous cell carcinoma arising within the jaws, having no initial connection with the oral mucosa, and presumably developing from residues of the odontogenic epithelium [1]. Swelling of the jaw and pain most often are the presenting signs and radiologically, bone loss is present (Fig. 6.4).

Fig. 6.4

Radiograph showing radiolucent lesion in right mandible; case of a primary intraosseous carcinoma masquerading as a radicular cyst

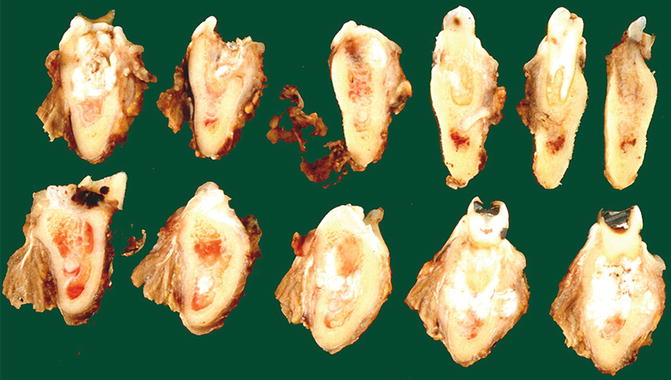

Gross examination reveals a tumor that is not confined to the jaw bone but spreads into adjacent soft tissues after perforating though the cortical bone (Figs. 6.5 and 6.6) and within the jaw there is extension through the periodontal ligament (Fig. 6.7). The tumor is composed by atypical squamous cells, ranging from well to poorly differentiated [6, 8], similar to squamous cell carcinoma occurring at other body sites including the oral mucosa. Therefore, one has to be sure that the tumor indeed is purely intraosseous, excluding that it is a mucosal squamous cell carcinoma that has invaded the underlying jaw bone (Fig. 6.8). In practice, this means that any connection of the lesion with the oral mucosa refutes a diagnosis of intraosseous carcinoma. Moreover, one has to exclude the possibility that the intraosseous lesion represents a metastastis from a primary squamous cell carcinoma elsewhere.

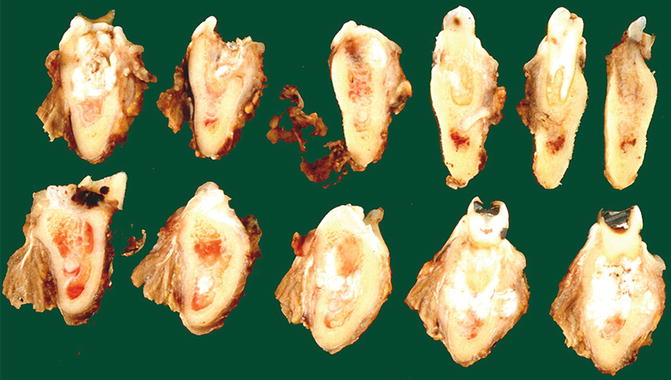

Fig. 6.5

Mandibular slices of a primary intraosseous carcinoma. Tumor surrounds roots and shows extension in soft tissue. Same case as shown in Fig. 6.4

Fig. 6.7

Higher magnification of primary intraosseous carcinoma to illustrate tumor growth between jaw bone and tooth surface

Fig. 6.8

Massive involvement of mandible by keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma also surrounding impacted tooth. This could also be due to deep bony invasion from a mucosal squamous cell carcinoma. It has to be emphasized that a diagnosis of primary intraosseous carcinoma requires exclusion of any mucosal involvement

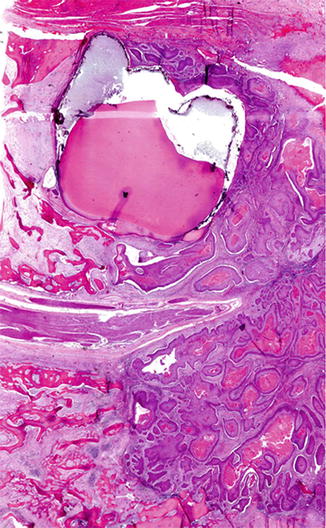

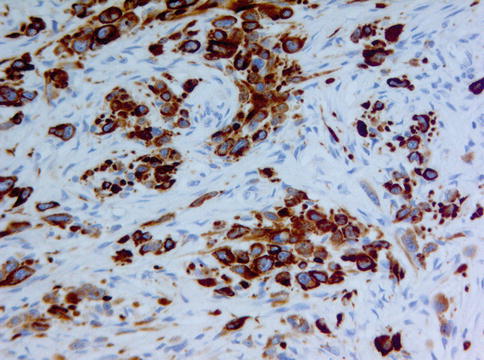

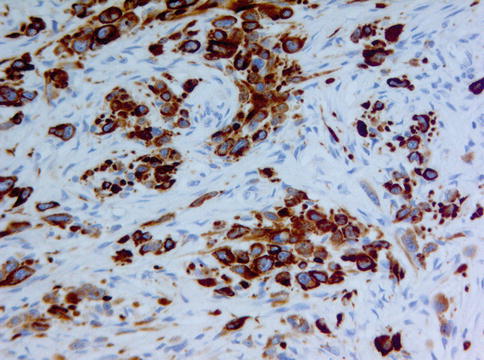

Rarely, intraosseous carcinoma is connected with another jaw lesion, such as the epithelial lining of an odontogenic cyst [11, 12], or with the enamel epithelium that lines the tooth crown before eruption (Figs. 6.9 and 6.10) [13]; they could represent the tissue from which the tumor has arisen but a collision phenomenon cannot be excluded. Occasionally, primary intraosseous carcinoma may show the appearance of a spindle cell carcinoma, immunohistochemistry needed to reveal the epithelial nature of the tumor cells (Figs. 6.11 and 6.12). If there is also extensive bone remodeling, such cases may be mistaken for osteosarcoma (Fig. 6.13).

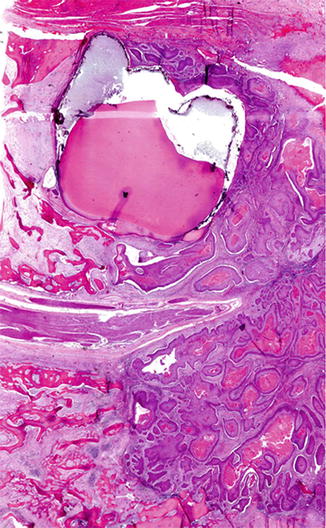

Fig. 6.9

Primary intraosseous carcinoma surrounding the crown of an impacted tooth

Fig. 6.10

Higher magnification of Fig. 6.9 to illustrate the continuity of the tumor with the tooth crown (empty space due to loss of the enamel due to decalcification)

Fig. 6.11

Intraosseous spindle cell carcinoma showing aggregates of atypical cells. Immunohistochemistry (see Fig. 6.12) showed an epithelial component expressing keratin revealing the nature of this spindle cell neoplasm

Fig. 6.12

Spindle cell carcinoma: atypical cells expressing keratin forming nests and lying single

Resection and postoperative radiotherapy seem to provide the best treatment results. However, the prognosis is poor because of frequent metastases to regional lymph nodes and lungs, with almost 50 % of the patients failing loco-regionally within the first 2 years of follow-up [14].

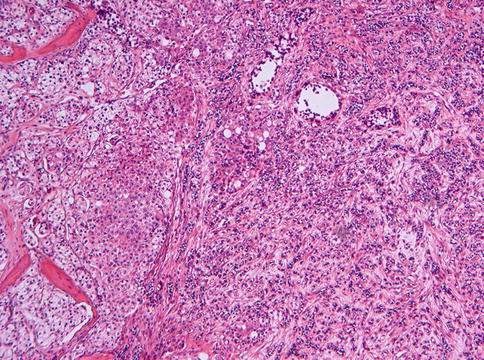

6.5 Clear Cell Odontogenic Carcinoma

Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma was initially reported as clear cell odontogenic tumor [15] , the latter designation being dropped as this lesion has shown a metastatic potential [16].

Usually, the lesion shows progressive jaw expansion with teeth loosening as the most frequent presentation, the anterior mandible being the preferred localisation [17–19]. Radiologically, it appears as an ill-defined radiolucency and gross examination reveals spread beyond the confines of the jaw (Figs. 6.14 and 6.15).

Fig. 6.14

Radiograph of clear cell odontogenic carcinoma presenting itself as an ill-defined radiolucency in the right mandible

Fig. 6.15

Gross view of mandibular clear cell odontogenic carcinoma to illustrate the extension into perimandibular soft tissues, remnants of the original cortical bone still discernable

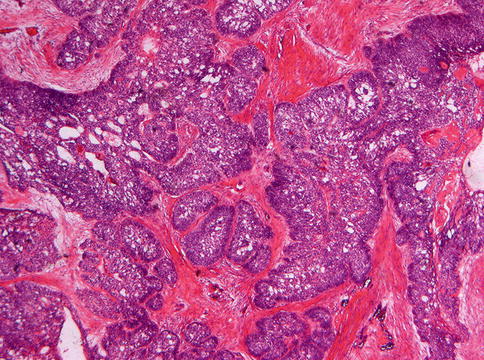

Histologically, the tumor is more frequently composed of cells with clear cytoplasm, hyperchromatic nuclei and well-defined borders, arranged in strands or large nests (Fig. 6.16) [17]. These cells coexist with variable proportions of smaller polygonal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and dark nuclei (Figs. 6.17 and 6.18). In rarer instances, the tumor may be exclusively composed by a clear cell population and, occasionally, focal squamous cell differentiation has also been reported [18].

Fig. 6.16

Histological picture of clear cell odontogenic carcinoma composed of cells with clear cytoplasm, hyperchromatic nuclei and well-defined borders, arranged in strands or large nests. There is no peripheral palisading

Fig. 6.17

Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma may also contain smaller cells with compact nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm

Fig. 6.18

Sometimes, the tiny strands in clear cell odontogenic carcinoma may be composed exclusively of cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm

The clear cells stain variably positive for glycogen with PAS, this staining disappearing after diastase-pretreatment and mucin stains are negative. Immunohistochemically, there is expression of epithelial markers such as keratin AE1/AE3, cytokeratins 8–18, cytokeratin 19 and Epithelial Membrane Antigen [19].

Clear cell odontogenic carcinoma has to be distinguished from other lesions that have clear cells as their main morphology. This includes metastatic renal cell carcinoma as the most likely alternative, the clear cell variant of mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and ameloblastoma with clear cells being rare. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma mainly can be ruled out by an appropriate diagnostic work-up of the patient. The clear cell variant of muco-epidermoid carcinoma can be properly identified with stains for mucin production. Differentiation from ameloblastoma with clear cells may be problematic and it has been proposed that these lesions may be histogenetically related, as previously mentioned [20] but this diagnostic dilemma has little clinical significance as both ameloblastoma and clear cell odontogenic carcinoma require excision with a margin including healthy tissue. Furthermore, the recently identified odontogenic carcinoma with dentinoid enters the differential diagnosis as the majority of them also contain clear cells [21].

Whether the genetic changes recently found in clear cell odontogenic carcinoma will be diagnostically useful, has yet to be determined [22].

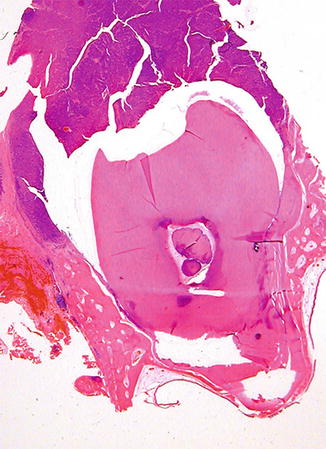

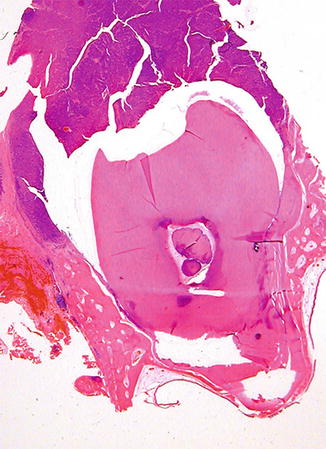

6.6 Malignant Epithelial Odontogenic Ghost Cell Tumor

Malignant epithelial odontogenic ghost cell tumor, also called ghost cell odontogenic carcinoma according to the latest WHO classification [1], is a tumor that combines the characteristics of a calcifying cystic odontogenic tumor with cytonuclear atypia indicating malignancy and that often arises through malignant transformation of a pre-existing benign calcifying cystic odontogenic tumor [23].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree