![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, the pharmacy student, community practice resident, or pharmacist should be able to:

1. List three variables contributing to the increased prevalence of obesity.

2. Calculate a patient’s body mass index (BMI) when given a patient’s height and weight.

3. Assess a patient’s risk for other comorbid disease states.

4. Compare nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment options/alternatives for patients, including contraindications and side effects, and formulate a treatment plan.

5. Identify various roles community pharmacists can have in weight management as well as the benefits and barriers for patients who want to participate in a community pharmacist managed weight management clinic.

6. Develop a business plan for implementing a weight management service.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The problem of obesity is a nationwide crisis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that in 2009–2010, 35.7% or over 78 million adults were classified as obese.1–5 This is a problem that extends into the pediatric/adolescent population with the 2004 overweight prevalence ranging from 5% for children aged 2–5 and 17.4% for adolescents up to 19 years of age and obese prevalence for 2009–2010 for adolescents aged 2–19 at 16.9%.1,5 The prevalence of obesity is higher among certain ethnic groups. Figure 14–1 highlights some ethnic groups and their incidence of obesity.3 Native American and Alaska natives are also ethnic groups that tend to have high obesity prevalence (32.4%).3

Figure 14–1. Incidence of Obesity by Ethnic Group/Gender

The economic impact of obesity is staggering. The CDC reported that the total medical costs of obesity in adults reached $147 billion in 2008 with people who are obese paying 42% more in health-care costs than normal-weight individuals.1,3,6 These costs are attributed to the conditions and health risks associated with obesity and not the medications used for treating obesity.7 Both Medicare and Medicaid pay about $1000–1700 more for obese patients than normal-weight patients.3 In children, the costs are estimated to be $14.3 billion.8 Other areas of impact include productivity, transportation, and human capital costs.8Studies have demonstrated the productivity loss for obesity-related “absenteeism” and “presenteeism” to be as high as $11 billion annually.8 Productivity costs are also increased due to higher rates of disability costs and premature mortality.8 Transportation costs are increased due to higher weight-based fuel needs. It is estimated that in 2000, the extra fuel costs for airlines due to higher numbers of obese passengers were about $275 million.8 Major airlines such as Southwest Airlines and American Airlines now request customers of “certain size” to purchase two seats on the airplane. Studies have also shown that there is a link between education experience and obesity with obese students having increased absenteeism and in the end, lower income or education attainment.8

This problem is so severe and widespread that the CDC’s Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity Program to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Disease States allots millions of dollars to assist states with funding to address this epidemic at the state and community level.1,4 Their mission is to “lead strategic public health efforts to prevent and control obesity, chronic disease, and other health conditions through regular physical activity and good nutrition.”4 Target areas include increase in physical activity, increase in consumption of fruits and vegetables, decrease in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, increase in breastfeeding, and decrease in television viewing.1

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is designed to assess the health and nutritional status of the United States. Data from the 1976–1980 and 2005–2006 surveys demonstrate a shift in BMI distribution from peaking around 20–25 to 24–30, respectively.2 This shift implies that the population, as a whole, is heavier. In fact, in 1990, the majority of the states had a population in which 10–14% were in the obese category.9 In 8 years, the majority of the states had populations in which >15% were obese.9 Jumping to 2007, the majority of the states (36) had a population in which >25% were obese.9 Now, all states have a >20% obesity prevalence.9 Twelve states have a prevalence of 30% or more including Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia.4 The state with the highest prevalence in 2010 was Mississippi at 34%.9 Oklahoma is expected to have the highest rate of obesity by 2018.10

Etiology

There are several factors that have contributed to the prevalence of obesity. The CDC summed it up well when they stated that “American society (is) ‘obesogenic’ characterized by environments that promote increased food intake, nonhealthful foods, and physical inactivity.”10 Some of these risk factors are easier to control than others. Genetics, for example, is a risk factor that one may find challenging.11 Research has shown that there are genetic defects related to the development of obesity.11 The cultural environment is a modifiable risk factor. In a society that is so focused on convenience and super-sized fast-food items, we have, essentially, put ourselves in this epidemic. It can be also argued that the economic state has a direct relationship with the prevalence of obesity. When families experience financial constraints, expensive and nutritious product is often replaced with unhealthy, high-calorie, cheaper fast-food alternatives. Time constraints also encourage fast-food alternatives.12 These fast-food alternatives have a poor satiety value encouraging overconsumption.12 Interestingly, the prices of several commodity-driven products has decreased from 1982 to 2008.12 Sugar and sweets have decreased by 15%, fats and oil by 10%, and carbonated drinks by 34%.12 The price of fresh fruits and vegetables increased by over 50%.12 To add to this, energy consumption has increased by about 300 kcal/day during this same time while physical activity levels declined.12 People are more sedentary now with televisions, computers, office jobs, and electronic games to keep them stationary and not moving.12 Lack of physical inactivity is one of the biggest contributing factors to the obese state of our nation. Only 31% of US adults report routine physical activity (defined as at least 3 sessions/week lasting at least 20 minutes/session).3

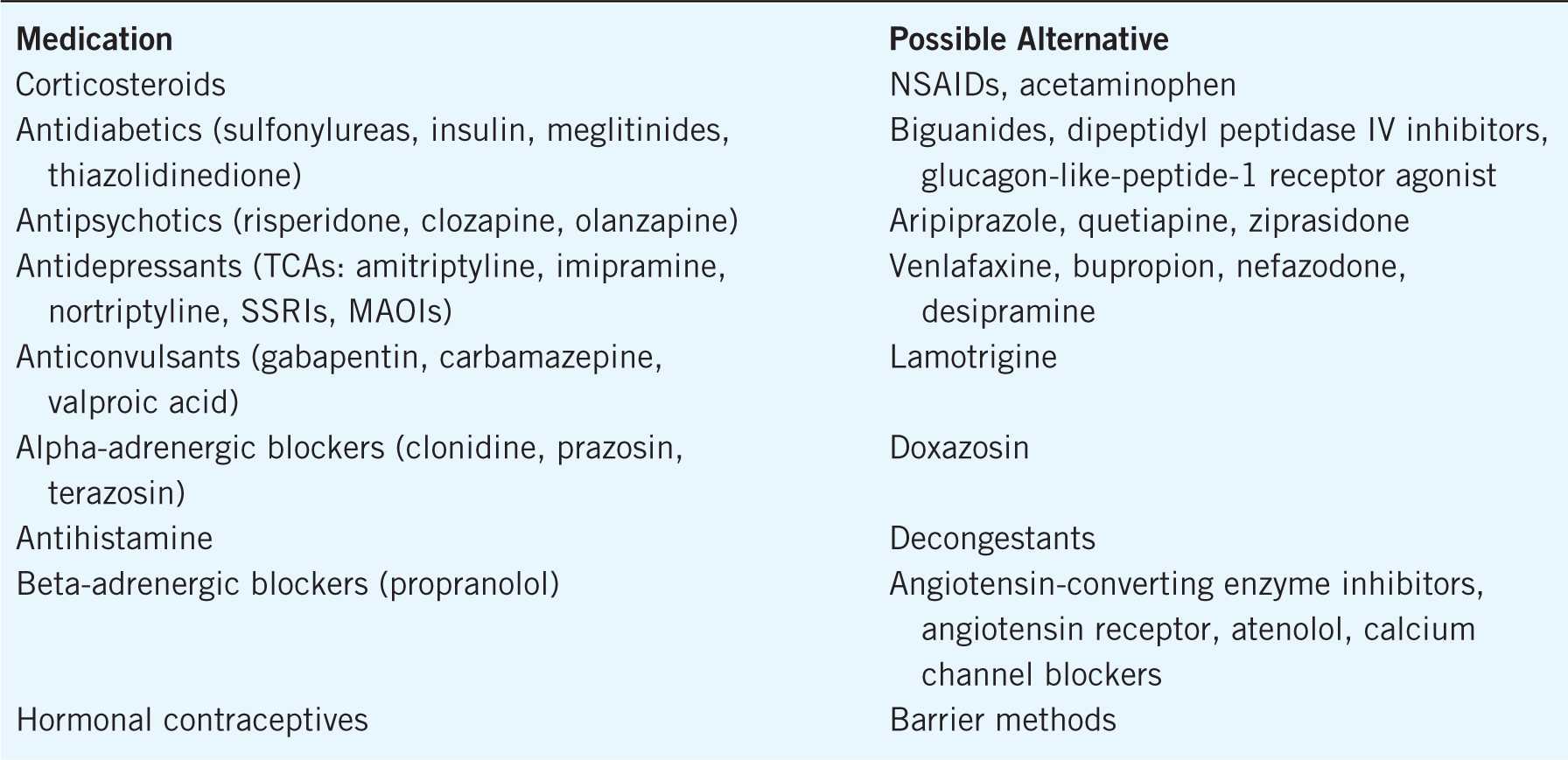

Certain medications put a patient at risk of gaining weight.13 Many antipsychotics and antidepressants have significant weight gain associated with them. Table 14–1 lists some common prescription medications and possible alternative choices that do not have weight gain associated with them or if they do, not as significant as the original medication prescribed.

Table 14–1. Medications that Can Cause Weight Gain

In addition to medications, there are certain disease states that put a patient at increased risk of weight gain. These include hypothyroid, congestive heart failure, and Cushing syndrome.

Classification

Table 14–2 outlines the classifications of obesity.14

Table 14–2. Classification of Overweight and Obesity

BMI is calculated by total body weight (kg)/height squared (m2) or as weight (lbs)/height (in2) × 703. It is the most common screening test for obesity and describes weight as a function of height and is strongly correlated with total body fat content.14,15Confounding factors can affect weight and the applicability of BMI classifications. These include edematous stages (e.g., congestive heart failure and pregnancy), extreme muscularity commonly seen in athletes, muscle wasting, short-stature, and Asian-Pacific ethnic background.16 BMI does not distinguish between lean muscle and fat tissue. As a result, athletes may have a higher BMI.16

Increased Health Risks

Waist circumference is an independent predictor of cardiovascular risk factors and morbidity.14 Studies have shown that people with larger waist circumferences are at increased cardiovascular risk.16 In men, the cutoff is >40 inches and in women >35 inches.14 Waist circumference is measured by

“locating the upper hip bone and the top of the right iliac crest. Place a measuring tape in a horizontal plane around the abdomen at the level of the iliac crest. Before reading the tape measure, ensure that the tape is snug, but does not compress the skin, and is parallel to the floor. The measurement is made at the end of a normal expiration”16 (see Fig. 14–2).

Figure 14–2. Waist circumference measurement.

The corresponding diseased risk in obese patients can be seen in Table 14–3. Waist-to-hip ratio can also identify cardiovascular risk (normal ratio for women ≤0.8 and men ≤0.9).15 People that are overweight or obese have increased risk of certain disease states and health risks. Table 14–3 lists several of these disease states.3,8,11,12,14,16

Table 14–3. Disease States and Health Risks Associated with Obesity

Having existing comorbid diseases puts overweight and obese patients at increased risk of overall mortality and for further complications associated with their disease states.14,17

There are numerous examples in the literature demonstrating the health risk associated with obesity as well as the positive effects of weight loss on comorbid disease states. With diabetes, for example, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes increases as BMI increases and is three to seven times more prevalent in people with BMI >35 kg/m2. However, it has been demonstrated that a 5% weight loss can improve insulin action and decrease fasting blood glucose levels.18 Intentional weight loss (reducing BMI from 33.5 to 27.7 kg/m2) has been associated with a 25% reduction in mortality rates in overweight patients with diabetes.11

The risk of hypertension is 40% higher in obese individuals.19 A 10-kg higher weight is associated with 3 mm Hg higher systolic and 2.3 mm Hg higher diastolic blood pressure.11 Hypertension increases the risk of stroke and coronary heart disease.11 The Trials of Hypertension Prevention Phase II study demonstrated that long-term reductions in blood pressure and reduced risk of hypertension can be achieved with weight loss.20 The largest reductions in blood pressure were 7 mm Hg diastolic and 5 mm Hg systolic.20 Weight reduction can lead to significant decreases in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides and an increase in high-density lipoprotein.21

There is evidence that obesity also greatly increases the risk of various cancers. There is a 55% increased risk of colon cancer in men and 19% increased risk of pancreatic cancer in those with a higher BMI.22 Obesity increases the risk of chronic kidney disease, which in turn, increases the risk of cardiovascular disease.23

It is also well documented that obesity negatively affects general quality of life and has increased generalized health complaints such as headaches, indigestion, constipation, joint pain, chronic fatigue, and bladder infections associated with it.24,25

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Goals of Treatment

The general goals for weight loss and management are (1) to prevent further weight gain, (2) to reduce body weight, and (3) to maintain a lower body weight over the long term.14 The guidelines recommend targeting a weight-loss goal of 10% over 6 months or a weight loss of about 1—2 pounds/week.14

Initial assessment of a patient should include a thorough workup including history of weight gain, prescription and nonprescription medications, coexisting disease states, labs, previous approaches to weight loss, dietary habits, physical activity, readiness to change, goals, and available support system.26 Patients are advised to weigh themselves on a weekly basis. However, this is controversial. Some studies promote daily weighing.27,28 Other studies have found daily weighing can negate patient’s motivation and self-confidence as daily weights will normally fluctuate.29

Treatment—Therapeutic Lifestyle and Behavioral Changes

The Health Belief Model and the Transtheoretical Model of Change provide the basis for lifestyle and behavioral counseling associated with successful weight management programs.29 The Health Belief Model states that patients’ willingness to adopt, change, or maintain a health-related behavior depends on whether they:

![]() Perceive themselves as susceptible to a particular health problem

Perceive themselves as susceptible to a particular health problem

![]() View the problem or its consequences as serious

View the problem or its consequences as serious

![]() Are convinced that the recommended treatment or behavior will be effective, yet not be overly costly, inconvenient, or painful

Are convinced that the recommended treatment or behavior will be effective, yet not be overly costly, inconvenient, or painful

![]() Are exposed to a cue to take a health action29–32

Are exposed to a cue to take a health action29–32

In other words, patients will be more likely to be successful with weight management programs if they have a coexisting condition exacerbated by obesity or at increased risk of other health conditions related to obesity. The Transtheoretical Model of Change involves five stages of progression that identify how ready a patient is to change.29–32 These stages of change are precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Patients will go through each stage several times before they succeed in their long-term goals.29–32 Identifying which stage the patient is in can be helpful in forming the appropriate approach to their plan.

When initiated together, therapeutic lifestyle changes and behavioral counseling increase the chances of successful treatment. However, before any counseling takes place, it is important to assess why the patient wants to lose weight, what their goals are, and how confident they are.16 The answers to these questions will help formulate the overall treatment plan. Their reasoning in starting a weight-loss program may be their motivating factor; this reason as well as new motivators that might be discovered throughout the course of the program should be visited continuously as a consistent reminder to the patient as to why they are doing this. The patient’s goal may not be realistic, which can lead to overall frustration, drop in confidence and motivation, and ultimately, giving up on the program. Most patients have a dramatic difference between expectations and realistic goals;29 therefore, it is important to address this from the very beginning. Key features of programs addressing behavioral changes include goal setting, self-monitoring, environmental modifications, cognitive restructuring, and prevention of relapse.26

Addressing barriers and learning about resources and basics of nutrition are critical components. These strategies provide patients with the skills and motivation it takes to succeed. This strategy is what Dr. Terry Forshee (see section “Expert Interview”) follows in his weight management clinic, “Real change comes from the information the patient gets during the program combined with a readiness to change.”

A recommended method to identify barriers or triggers for weight gain is to have the patient draw out a time line of their weights over the years and then identify major life events that correspond to the various weights; these weight-changing events would vary for each person. Fig. 14–3 provides a fictional example.

Figure 14–3. Weight time line.

Commonly, patterns will emerge that correlate periods of weight gain to major life events or stressors.16 A method to evaluate physical activity is having the patient keep an activity journal similar in concept to blood sugar diaries for patients with diabetes or headache diaries for migraineurs.16 It allows the patients to become more aware of their own habits and perhaps, barriers. Or, a straightforward question “what gets in the way or interferes with you consistently engaging in physical activity?” can help identify barriers that should be addressed.16 On the opposite end of the spectrum, patients can identify activities they engage in that promote physical activity. Examples of additional assessment questions that can be asked to evaluate physical activity include:

![]() What is the most active thing you do in a typical day?

What is the most active thing you do in a typical day?

![]() What types of activities do you enjoy and how often do you engage in them?

What types of activities do you enjoy and how often do you engage in them?

![]() Do you enjoy doing activities alone/in private or with others/in public?

Do you enjoy doing activities alone/in private or with others/in public?

![]() How many hours each day do you spend in front of a television or computer?

How many hours each day do you spend in front of a television or computer?

![]() What types of exercise equipment or videos/DVD do you have at home?

What types of exercise equipment or videos/DVD do you have at home?

![]() What is your attitude about exercise?

What is your attitude about exercise?

![]() What types of activities have you done in the past that you do not currently do?

What types of activities have you done in the past that you do not currently do?

![]() What hurts/aches during or after exercising?

What hurts/aches during or after exercising?

![]() What type of gym shoes do you wear and how often do you replace them?

What type of gym shoes do you wear and how often do you replace them?

![]() What types of exercises would you like to learn how to do?

What types of exercises would you like to learn how to do?

![]() When in your day do you have time to add in exercise?

When in your day do you have time to add in exercise?

![]() If you belonged to a health club, how many days per week did you go and what did you do when you were there?14

If you belonged to a health club, how many days per week did you go and what did you do when you were there?14

This same concept can be utilized with a food diary to evaluate food habits and behaviors. There are many approaches to keeping a food diary. Food diaries, at a minimum, should include information on all food eaten, including snacks, beverages consumes, serving sizes, and calorie total.29 It is important to record every single food item eaten no matter how small the serving appears or how little the calories are. When calculating energy input, output, and deficit, unrecorded calories add up quickly.29 Other items that should be recorded include the time of day the food was eaten; the location; whether the meal was eaten alone or with other people; and any emotions felt before, during, or after eating. This information is helpful in evaluating emotional, social, and environmental triggers to eating.29 Studies have shown that the number of food records kept per week was the best predictor of weight loss during a weight management program.29 Patients who kept food diaries with at least five entries lost twice as much weight as those who kept fewer records or no food diary at all.29

Dietary habits should be reviewed with the assistance of food logs, daily recall, or questionnaires.16 Daily intake should be modified to create a daily caloric deficit of about 500–1000 kcal/day.14 A 500 kcal deficit/day equates to about a 1 pound weight loss/week. In addition, education should be focused on making healthier food choices and reducing total fat intake to <30% of total daily calories.14 Achieving caloric deficit can be obtained by a true low-calorie diet but can also be manageable with accompanying physical activity. The National Institutes of Health recommend 1000–1200 calories for women trying to lose weight and 1200–1800 for men.14 A patient should always check with their primary care provider before starting an exercise routine or before limiting caloric intake. It is recommended that exercise should take place most days of the week for at least 30 minutes/day. Patients should be advised to start slow and gradually increase the duration and intensity of their exercise to achieve the goal of 30 minutes most days of the week.

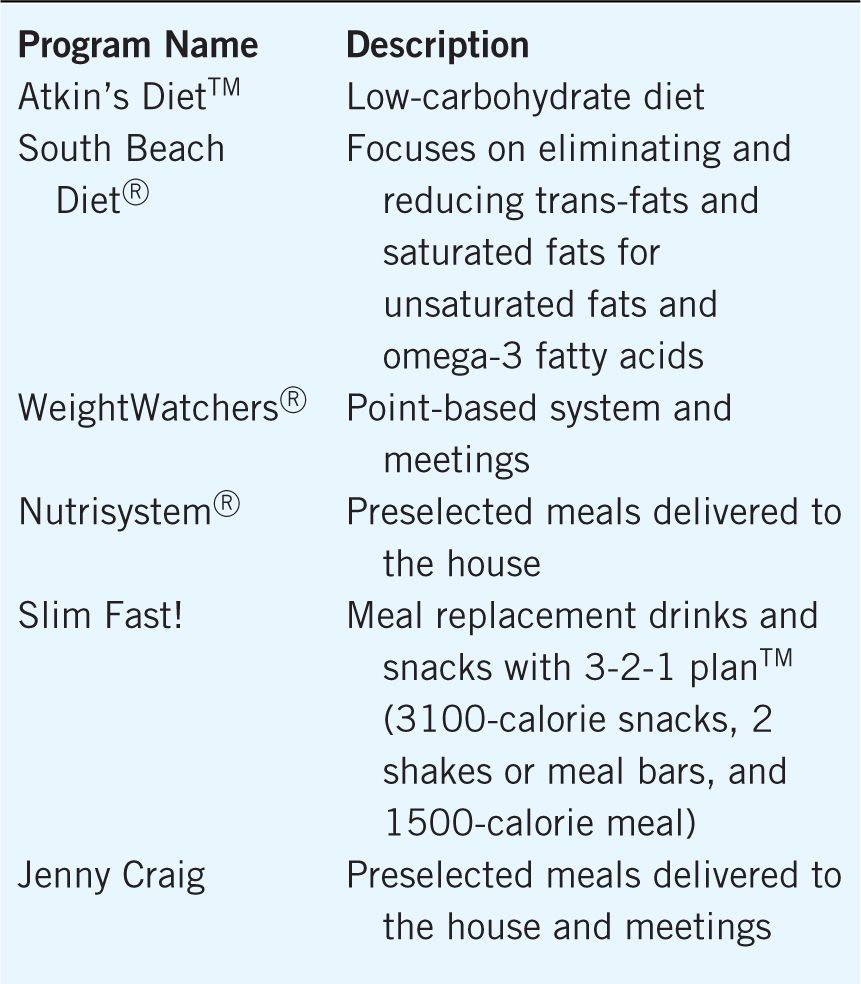

If patients have tried other weight-loss programs, the patient should be probed for further information (e.g., how much weight was lost, reasons for stopping, and advantages/disadvantages of the program) to identify further barriers.16 Some popular weight-loss programs are listed in Table 14–4. The patient’s baseline knowledge of obesity, contributing factors and health risks associated with obesity, can also be used as a motivating factor once the patient is made aware of them.

Table 14–4. Popular Weight-Loss Programs

There are special considerations for certain patient populations including geriatrics, pediatrics, and tobacco smokers. Assessing physical activity levels or barriers in the geriatric population should include questions addressing daily functioning skills to assess appropriateness of physical activity recommendations.16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree