O

Ocular deviation

Ocular deviation refers to abnormal eye movement that may be conjugate (both eyes move together) or disconjugate (one eye moves separately from the other). This common sign may result from ocular, neurologic, endocrine, and systemic disorders that interfere with the muscles, nerves, or brain centers governing eye movement. Occasionally, it signals a life-threatening disorder such as a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. (See Ocular deviation: Its characteristics and causes in cranial nerve damage, page 494.)

Normally, eye movement is directly controlled by the extraocular muscles innervated by the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerves (cranial nerves III, IV, and VI). Together, these muscles and nerves direct a visual stimulus to fall on corresponding parts of the retina. Disconjugate ocular deviation may result from unequal muscle tone (nonparalytic strabismus) or from muscle paralysis associated with cranial nerve damage (paralytic strabismus). Conjugate ocular deviation may result from disorders that affect the centers in the cerebral cortex and brain stem responsible for conjugate eye movement. Typically, such disorders cause gaze palsy— difficulty moving the eyes in one or more directions.

If the patient displays ocular deviation, take his vital signs immediately and assess him for altered level of consciousness (LOC), pupil changes, motor or sensory dysfunction, and severe headache. If possible, ask the patient’s family about behavioral changes. Is there a history of recent head trauma? Respiratory support may be necessary. Also, prepare the patient for emergency neurologic tests such as a computed tomography scan.

If the patient displays ocular deviation, take his vital signs immediately and assess him for altered level of consciousness (LOC), pupil changes, motor or sensory dysfunction, and severe headache. If possible, ask the patient’s family about behavioral changes. Is there a history of recent head trauma? Respiratory support may be necessary. Also, prepare the patient for emergency neurologic tests such as a computed tomography scan.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient isn’t in distress, find out how long he has had the ocular deviation. Is it accompanied by double vision, eye pain, or headache? Also, ask if he has noticed any associated motor or sensory changes, or fever.

Check for a history of hypertension, diabetes, allergies, and thyroid, neurologic, or muscular disorders. Then obtain a thorough ocular history. Has the patient ever had extraocular muscle imbalance, eye or head trauma, or eye surgery?

During the physical examination, observe the patient for partial or complete ptosis. Does he spontaneously tilt his head or turn his face to compensate for ocular deviation? Check for eye redness or periorbital edema. Assess visual acuity, then evaluate extraocular muscle function by testing the six cardinal fields of gaze.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Brain tumor. The nature of ocular deviation depends on the site and extent of the tumor. Associated signs and symptoms include headaches that are most severe in the morning, behavioral changes, memory loss, dizziness, confusion, vision loss, motor and sensory dysfunction, aphasia and, possibly, signs of hormonal imbalance. The patient’s LOC may slowly deteriorate from lethargy to coma. Late signs

include papilledema, vomiting, increased systolic blood pressure, widening pulse pressure, and decorticate posture.

include papilledema, vomiting, increased systolic blood pressure, widening pulse pressure, and decorticate posture.

Ocular deviation: Its characteristics and causes in cranial nerve damage

Characteristics | Cranial nerve and extraocular muscles involved | Probable causes |

Inability to move the eye upward, downward, inward, and outward; drooping eyelid; and, except in diabetes, adilated pupil in the affected eye | Oculomotor nerve (III); medial rectus, superior rectus, inferior rectus, and inferior oblique muscles | Cerebral aneurysm, diabetes, temporal lobe herniation from increased intracranial pressure, brain tumor |

Loss of downward and outward movement in the affected eye | Trochlear nerve (IV); superior oblique muscle | Head trauma |

Loss of outward movement in the affected eye | Abducens nerve (VI); lateral rectus muscle | Brain tumor |

♦ Cavernous sinus thrombosis. In this disorder, ocular deviation may be accompanied by diplopia, photophobia, exophthalmos, orbital and eyelid edema, corneal haziness, diminished or absent pupillary reflexes, and impaired visual acuity. Other features include high fever, headache, malaise, nausea and vomiting, seizures, and tachycardia. Retinal hemorrhages and papilledema are late signs.

♦ Cerebral aneurysm. When an aneurysm near the internal carotid artery compresses the oculomotor nerve, it may produce features that resemble third cranial nerve palsy. Typically, ocular deviation and diplopia are the presenting signs. Other cardinal findings include ptosis, a dilated pupil on the affected side, and a severe, unilateral headache, usually in the frontal area. Rupture of the aneurysm abruptly intensifies the pain, which may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Bleeding from the site causes meningeal irritation, resulting in nuchal rigidity, back and leg pain, fever, irritability, occasional seizures, and blurred vision. Other signs and symptoms associated with intracranial bleeding include hemiparesis, dysphagia, and visual defects.

♦ Diabetes mellitus. A leading cause of isolated third cranial nerve palsy, especially in the middleage patient with long-standing mild diabetes, this disorder may cause ocular deviation and ptosis. Typically, the patient also complains of sudden onset of diplopia and pain.

♦ Encephalitis. This infection causes ocular deviation and diplopia in some patients. Typically, it begins abruptly with fever, headache, and vomiting, followed by signs of meningeal irritation (for example, nuchal rigidity) and of neuronal damage (for example, seizures, aphasia, ataxia, hemiparesis, cranial nerve palsies, and photophobia). The patient’s LOC may rapidly deteriorate from lethargy to coma within 24 to 48 hours after onset.

♦ Head trauma. The nature of ocular deviation depends on the site and extent of head trauma. The patient may have visible soft-tissue injury, bony deformity, facial edema, and clear or bloody otorrhea or rhinorrhea. Besides these obvious signs of trauma, he may also develop blurred vision, diplopia, nystagmus, behavioral changes, headache, motor and sensory dysfunction, and a decreased LOC that may progress to coma. Signs of increased intracranial pressure— such as bradycardia, increased systolic pressure, and widening pulse pressure—may also occur.

♦ Multiple sclerosis. Ocular deviation may be an early sign of this disorder. Accompanying it are diplopia, blurred vision, and sensory dysfunction, such as paresthesia. Other signs and symptoms include nystagmus, constipation, muscle weakness, paralysis, spasticity, hyperreflexia, intention tremor, gait ataxia, dysphagia, dysarthria, impotence, and emotional instability. In addition, the patient may experience urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence.

♦ Myasthenia gravis. Ocular deviation may accompany the more common presenting signs

of diplopia and ptosis. This disorder may affect only the eye muscles, or it may progress to other muscle groups, causing altered facial expression, difficulty chewing, dysphagia, weakened voice, and impaired fine hand movements. Signs of respiratory distress reflect weakness of the diaphragm and other respiratory muscles.

of diplopia and ptosis. This disorder may affect only the eye muscles, or it may progress to other muscle groups, causing altered facial expression, difficulty chewing, dysphagia, weakened voice, and impaired fine hand movements. Signs of respiratory distress reflect weakness of the diaphragm and other respiratory muscles.

♦ Ophthalmoplegic migraine. Most common in young adults, this disorder produces ocular deviation and diplopia that persist for days after the pain subsides. Associated signs and symptoms include unilateral headache, possibly with ptosis on the same side; temporary hemiplegia; and sensory deficits. Irritability, depression, or slight confusion may also occur.

♦ Orbital blowout fracture. In this fracture, the inferior rectus muscle may become entrapped, resulting in limited extraocular movement and ocular deviation. Typically, the patient’s upward gaze is absent; other directions of gaze may be affected if edema is dramatic. The globe may also be displaced downward and inward. Associated signs and symptoms include pain, diplopia, nausea, periorbital edema, and ecchymosis.

♦ Orbital cellulitis. This disorder may cause sudden onset of ocular deviation and diplopia. Other signs and symptoms include unilateral eyelid edema and erythema, hyperemia, chemosis, and extreme orbital pain. Purulent discharge makes eyelashes matted and sticky. Proptosis is a late sign.

♦ Orbital tumor. Ocular deviation occurs as the tumor gradually enlarges. Associated findings include proptosis, diplopia and, possibly, blurred vision.

♦ Stroke. This life-threatening disorder may cause ocular deviation, depending on the site and extent of the stroke. Accompanying features are also variable and include altered LOC, contralateral hemiplegia and sensory loss, dysarthria, dysphagia, homonymous hemianopsia, blurred vision, and diplopia. In addition, the patient may develop urine retention or incontinence or both, constipation, behavioral changes, headache, vomiting, and seizures.

♦ Thyrotoxicosis. This disorder may produce exophthalmos—proptotic or protruding eyes— which, in turn, causes limited extraocular movement and ocular deviation. Usually, the patient’s upward gaze weakens first, followed by diplopia. Other features are lid retraction, a wide-eyed staring gaze, excessive tearing, edematous eyelids and, sometimes, inability to close the eyes. Cardinal features of thyrotoxicosis include tachycardia, palpitations, weight loss despite increased appetite, diarrhea, tremors, an enlarged thyroid, dyspnea, nervousness, diaphoresis, heat intolerance, and an atrial or ventricular gallop.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs and neurologic status if you suspect an acute neurologic disorder. Take seizure precautions, if necessary. Also, prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as blood studies, orbital and skull X-rays, and computed tomography scan.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

In children, the most common cause of ocular deviation is nonparalytic strabismus. Normally, children achieve binocular vision by age 3 to 4 months. Although severe strabismus is readily apparent, mild strabismus must be confirmed by tests for misalignment, such as the corneal light reflex test and the cover test. Testing is crucial— early corrective measures help preserve binocular vision and cosmetic appearance. Also, mild strabismus may indicate retinoblastoma, a tumor that may be asymptomatic before age 2 except for a characteristic whitish reflex in the pupil.

Oligomenorrhea

In most women, menstrual bleeding occurs every 28 days plus or minus 4 days. Although some variation is normal, menstrual bleeding at intervals of greater than 36 days may indicate oligomenorrhea—abnormally infrequent menstrual bleeding characterized by three to six menstrual cycles per year. When menstrual bleeding does occur, it’s usually profuse, prolonged (up to 10 days), and laden with clots and tissue. Occasionally, scant bleeding or spotting occurs between these heavy menses.

Oligomenorrhea may develop suddenly or it may follow a period of gradually lengthening cycles. Although oligomenorrhea may alternate with normal menstrual bleeding, it can progress to secondary amenorrhea.

Because oligomenorrhea is commonly associated with anovulation, it’s common in infertile, early postmenarchal, and perimenopausal women. This sign usually reflects abnormalities of the hormones that govern normal endometrial function. It may result from ovarian, hypothalamic, pituitary, and other metabolic

disorders, and from the effects of certain drugs. It may also result from emotional or physical stress, such as sudden weight change, debilitating illness, or rigorous physical training.

disorders, and from the effects of certain drugs. It may also result from emotional or physical stress, such as sudden weight change, debilitating illness, or rigorous physical training.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

After asking the patient’s age, find out when menarche occurred. Has the patient ever experienced normal menstrual cycles? When did she begin having abnormal cycles? Ask her to describe the pattern of bleeding. How many days does the bleeding last, and how frequently does it occur? Are there clots and tissue fragments in her menstrual flow? Note when she last had menstrual bleeding.

Next, determine if she’s having symptoms of ovulatory bleeding. Does she experience mild, cramping abdominal pain 14 days before she bleeds? Is the bleeding accompanied by premenstrual symptoms, such as breast tenderness, irritability, bloating, weight gain, nausea, and diarrhea? Does she have cramping or pain with bleeding? Also, check for a history of infertility. Does the patient have any children? Is she trying to conceive? Ask if she’s currently using hormonal contraceptives or if she’s ever used them in the past. If she has, find out when she stopped taking them.

Then ask about previous gynecologic disorders such as ovarian cysts. If the patient is breast-feeding, has she experienced any problems with milk production? If she hasn’t been breast-feeding recently, has she noticed milk leaking from her breasts? Ask about recent weight gain or loss. Is the patient less than 80% of her ideal weight? If so, does she claim that she’s overweight? Ask if she’s exercising more vigorously than usual.

Screen for metabolic disorders by asking about excessive thirst, frequent urination, or fatigue. Has the patient been jittery or had palpitations? Ask about headache, dizziness, and impaired peripheral vision. Complete the history by finding out what drugs the patient is taking.

Begin the physical examination by taking the patient’s vital signs and weighing her. Inspect for increased facial hair growth, sparse body hair, male distribution of fat and muscle, acne, and clitoral enlargement. Note if the skin is abnormally dry or moist, and check hair texture. Also, be alert for signs of psychological or physical stress. Rule out pregnancy by a blood or urine pregnancy test.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Adrenal hyperplasia. In this disorder, oligomenorrhea may occur with signs of androgen excess, such as clitoral enlargement and male distribution of hair, fat, and muscle mass.

♦ Anorexia nervosa. Anorexia nervosa may cause sporadic oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea. Its cardinal symptom, however, is a morbid fear of being fat associated with weight loss of more than 20% of ideal body weight. Typically, the patient displays dramatic skeletal muscle atrophy and loss of fatty tissue; dry or sparse scalp hair; lanugo on the face and body; and blotchy or sallow, dry skin. Other symptoms include constipation, decreased libido, and sleep disturbances.

♦ Diabetes mellitus. Oligomenorrhea may be an early sign in this disorder. In juvenile-onset diabetes, the patient may have never had normal menses. Associated findings include excessive hunger, polydipsia, polyuria, weakness, fatigue, dry mucous membranes, poor skin turgor, irritability and emotional lability, and weight loss.

♦ Hypothyroidism. Besides oligomenorrhea, this disorder may result in fatigue; forgetfulness; cold intolerance; unexplained weight gain; constipation; bradycardia; decreased mental acuity; dry, flaky, inelastic skin; puffy face, hands, and feet; hoarseness; periorbital edema; ptosis; dry, sparse hair; and thick, brittle nails.

♦ Polycystic ovary disease. About 25% of women with polycystic ovary disease have oligomenorrhea; but some may have amenorrhea, menometrorrhagia, or irregular menses. Infertility, anovulation, and enlarged, palpable ovaries are also common. Other features vary but may include signs of androgen excess— male distribution of body hair and muscle mass, facial hair growth, acne and, occasionally, obesity.

♦ Prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor. Oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea may be the first sign of a prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor. Accompanying findings include unilateral or bilateral galactorrhea, infertility, loss of libido, and sparse pubic hair. Headache and visual field disturbances—such as diminished peripheral vision, blurred vision, diplopia, and hemianopsia —signal tumor expansion.

♦ Sheehan’s syndrome. This pituitary necrosis usually follows severe obstetric hemorrhage. Oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea may occur with failure to lactate, sparse pubic and axillary hair, decreased libido, and fatigue.

♦ Thyrotoxicosis. This disorder may produce oligomenorrhea along with reduced fertility. Cardinal findings include irritability, weight loss despite increased appetite, dyspnea, tachycardia, palpitations, diarrhea, tremors, diaphoresis, heat intolerance, an enlarged thyroid and, possibly, exophthalmos.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Drugs that increase androgen levels— such as corticosteroids, corticotropin, anabolic steroids, danocrine, and injectable and implanted contraceptives—may cause oligomenorrhea. Hormonal contraceptives may be associated with delayed resumption of normal menses when their use is discontinued; however, 95% of women resume normal menses within 3 months. Other drugs that may cause oligomenorrhea include phenothiazine derivatives and amphetamines, and antihypertensive drugs, which increase prolactin levels.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as blood hormone levels, thyroid studies, or pelvic imaging studies.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Teenage girls may experience oligomenorrhea associated with immature hormonal function. However, prolonged oligomenorrhea or the development of amenorrhea may signal congenital adrenal hyperplasia or Turner’s syndrome.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Oligomenorrhea in the perimenopausal woman usually indicates impending onset of menopause.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Ask the patient to record her basal body temperature to determine if she’s having ovulatory cycles. Provide her with blank charts, and teach her how to keep them accurately. Have the patient use a home ovulation testing or urine luteinizing hormone kit to provide evidence of ovulation. Remind the patient that she may become pregnant since ovulation may still occur even though she isn’t menstruating normally. Discuss contraceptive measures, as appropriate.

Oliguria

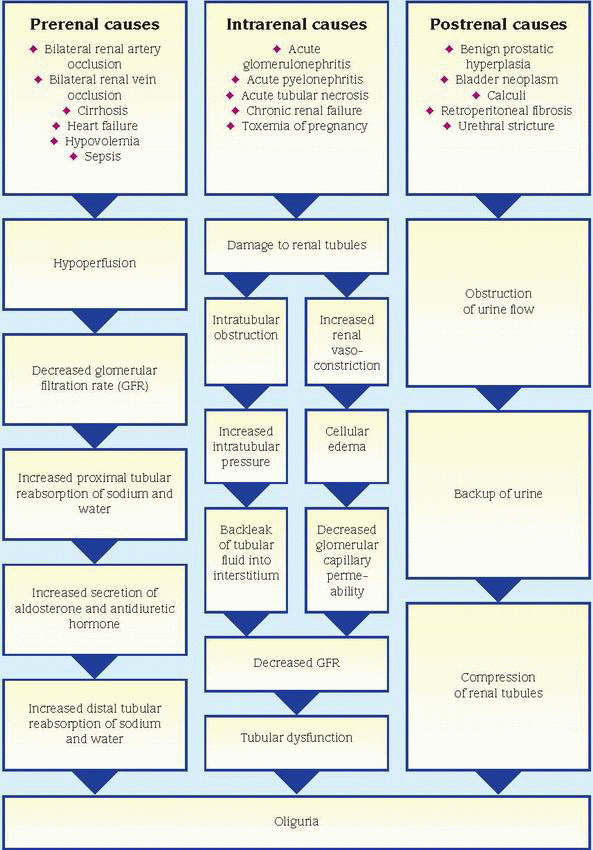

A cardinal sign of renal and urinary tract disorders, oliguria is clinically defined as urine output of less than 400 ml/24 hours. Typically, this sign occurs abruptly and may herald serious—possibly life-threatening—hemodynamic instability. Its causes can be classified as prerenal (decreased renal blood flow), intrarenal (intrinsic renal damage), or postrenal (urinary tract obstruction); the pathophysiology differs for each classification. (See How oliguria develops, page 498.) Oliguria associated with a prerenal or postrenal cause is usually promptly reversible with treatment, although it may lead to intrarenal damage if untreated. However, oliguria associated with an intrarenal cause is usually more persistent and may be irreversible.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Begin by asking the patient about his usual daily voiding pattern, including frequency and amount. When did he first notice changes in this pattern and in the color, odor, or consistency of his urine? Ask about pain or burning on urination. Has the patient had a fever? Note his normal daily fluid intake. Has he recently been drinking more or less than usual? Has his intake of caffeine or alcohol changed drastically? Has he had recent episodes of diarrhea or vomiting that might cause fluid loss? Next, explore associated complaints, especially fatigue, loss of appetite, thirst, dyspnea, chest pain, or recent weight gain or loss (in dehydration).

Check for a history of renal, urinary tract, or cardiovascular disorders. Note recent traumatic injury or surgery associated with significant blood loss, as well as recent blood transfusions. Was the patient exposed to nephrotoxic agents, such as heavy metals, organic solvents, anesthetics, or radiographic contrast media? Next, obtain a drug history.

Begin the physical examination by taking the patient’s vital signs and weighing him. Assess his overall appearance for edema. Palpate both kidneys for tenderness and enlargement, and percuss for costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness. Also, inspect the flank area for edema or erythema. Auscultate the heart and lungs for abnormal sounds, and the flank area for renal artery bruits. Assess the patient for edema or signs of dehydration such as dry mucous membranes.

Obtain a urine sample and inspect it for abnormal color, odor, or sediment. Use reagent strips to test for glucose, protein, and blood. Also, use a urinometer to measure specific gravity.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Acute tubular necrosis (ATN). An early sign of ATN, oliguria may occur abruptly (in shock) or gradually (in nephrotoxicity). Usually, it persists for about 2 weeks, followed by polyuria. Related features include signs of hyperkalemia (muscle weakness and cardiac arrhythmias); uremia (anorexia, confusion, lethargy, twitching, seizures, pruritus, and Kussmaul’s respirations); and heart failure (edema, jugular vein distention, crackles, and dyspnea).

♦ Benign prostatic hyperplasia. This disorder, which is common in men older than age 50, in rare cases may cause oliguria resulting from bladder outlet obstruction. More common symptoms include urinary frequency or hesitancy, urge or overflow incontinence, decrease in the force of the urine stream or inability to stop the stream, nocturia and, possibly, hematuria.

♦ Bladder neoplasm. Uncommonly, this disorder may produce oliguria if the tumor obstructs the bladder outlet. The cardinal signs of such obstruction include urinary frequency and urgency, as well as gross hematuria, which may lead to clot retention and flank pain.

♦ Calculi. Oliguria or anuria may result from stones lodging in the kidneys, ureters, bladder outlet, or urethra. Associated signs and symptoms include urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, and hematuria or pyuria. Usually, the patient experiences renal colic—excruciating pain that radiates from the CVA to the flank, the suprapubic region, and the external genitalia. This pain may be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, abdominal distention and, occasionally, fever and chills.

♦ Cholera. In this bacterial infection, severe water and electrolyte loss lead to oliguria, thirst, weakness, muscle cramps, decreased skin turgor, tachycardia, hypotension, and abrupt watery diarrhea and vomiting. Death may occur in hours without treatment.

♦ Cirrhosis. In severe cirrhosis, hepatorenal syndrome may develop with oliguria, in addition to ascites, edema, fatigue, weakness, jaundice, hypotension, tachycardia, gynecomastia, testicular atrophy, and signs of GI bleeding such as hematemesis.

♦ Glomerulonephritis (acute). This disorder produces oliguria or anuria. Other features are mild fever, fatigue, gross hematuria, proteinuria, generalized edema, elevated blood pressure, headache, nausea and vomiting, flank and abdominal pain, and signs of pulmonary congestion (dyspnea and productive cough).

♦ Heart failure. Oliguria may occur in left ventricular failure as a result of low cardiac output and decreased renal perfusion. Accompanying signs and symptoms include dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, peripheral edema, distended jugular veins, tachycardia, tachypnea, crackles, and a dry or productive cough. In advanced heart failure, the patient may also develop orthopnea, cyanosis, clubbing, ventricular gallop, diastolic hypertension, cardiomegaly, and hemoptysis.

♦ Hypovolemia. Any disorder that decreases circulating fluid volume can produce oliguria. Associated findings include orthostatic hypotension, apathy, lethargy, fatigue, gross muscle weakness, anorexia, nausea, profound thirst, dizziness, sunken eyeballs, poor skin turgor, and dry mucous membranes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree