3 Nutritional support in surgical patients

Introduction

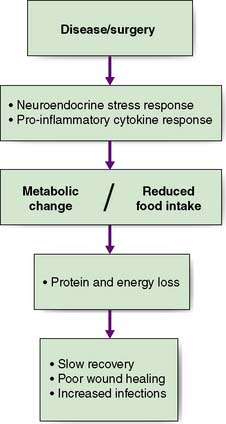

Nutritional disorders in surgical practice have two principal components. First, starvation can be initiated by the effects of the disease, by restriction of oral intake, or both. Simple starvation results in progressive loss of the body’s energy and protein reserves (i.e. subcutaneous fat and skeletal muscle). Second, there are the metabolic effects of stress/inflammation; namely, increased catabolism and reduced anabolism. These result in a variety of changes, including a low serum albumin concentration, accelerated muscle wasting and water retention. Although malnutrition may be the result of starvation, in most surgical patients it results from a combination of reduced food intake and metabolic change (Fig. 3.1).

Assessment of nutritional status

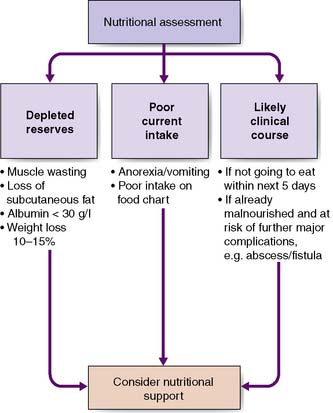

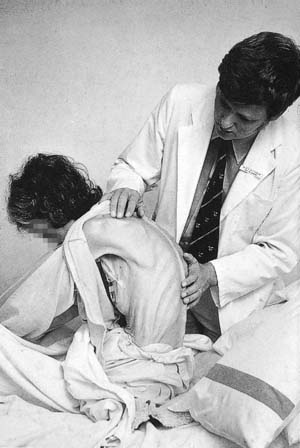

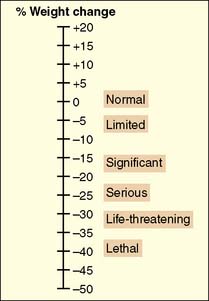

The key elements of nutritional assessment include current food intake, levels of energy and protein reserves, and the patient’s likely clinical course (Fig. 3.2). Patients who have not eaten for 5 days or more require nutritional support, and those with symptoms such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting or early satiety are at risk of a reduced food intake and hence undernutrition. Levels of energy reserves are most easily assessed by examining for loss of subcutaneous fat (skinfolds), whereas protein depletion is most commonly manifest as skeletal muscle wasting (Fig. 3.3). A history of weight loss of more than 10–15% is highly significant. Patients can also be assessed according to their body mass index – BMI = weight (kg)/height (m2). The normal BMI is 18.5–24.9. A value less than 18 is suggestive of significant protein-calorie undernutrition. Finally, it is important to recognize that in assessing the nutritional status of patients, knowledge of their likely clinical course is vital (Fig. 3.4). For example, if patients are well nourished, they should be able to withstand the brief period of fasting associated with major surgery. However, if patients are severely malnourished (e.g. weight loss of 15%, BMI 17), then even a short further period of starvation or catabolism may make them so critically undernourished that this may become life-threatening in itself. Taken together, a patient’s food intake, level of reserve and likely clinical course should alert the astute clinician to the need for nutritional support and should be part of the routine daily appraisal of every patient during a surgical ward round.

Summary Box 3.1 Body mass index (BMI)

18.5–24.9Ideal weight for height

25–29.9Over ideal weight for height

Summary Box 3.2 Nutritional status

• Nutritional status in surgical patients may be adversely affected by starvation (effects of disease such as oesophageal cancer, restricted intake), the effects of inflammation (increased catabolism) and the effects of the operation itself (stress/inflammatory response)

• Nutritional status is assessed by current food intake, levels of reserves and likely clinical course.

Assessment of nutritional requirements

Energy and protein/nitrogen requirements vary, depending on weight, body composition, clinical status, mobility and dietary intake. For most patients, an approximation based on weight and clinical status is sufficient. Relevant values are given in Table 3.1. Few adult patients require more than 25–30 kcal/kg/day (approximately 1800–2200 kcal in an adult of average body mass). Additional calories are unlikely to be used effectively and may even constitute a metabolic stress. Particular caution must be exercised when refeeding the chronically starved patient because of the dangers of hypokalaemia and hypophosphataemia (notably cardiac dysrhythmias).

Table 3.1 Estimation of energy and protein requirements in adult surgical patients

| Uncomplicated | Complicated/stressed | |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal/kg/day) | 25 | 30–35 |

| Protein (g/kg/day)* | 1.0 | 1.3–1.5 |

* Grams of protein can be converted to the equivalent amount of nitrogen by dividing by 6.25.

The most common method for assessing protein/nitrogen requirement is based on body weight (Table 3.1). Although more accurate assessment for patients receiving nutritional support can be derived from measurement of 24-hour urinary urea excretion, which can be converted to an estimate of 24-hour urinary nitrogen loss, this is seldom necessary in routine clinical practice.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree