Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Lymphadenitis

A. Atypical Mycobacterial Lymphadenitides

Definition

Lymphadenitides caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria.

Synonym

Nontuberculous mycobacterial lymphadenitides.

Etiology

A variety of mycobacteria, referred to as nontuberculous or atypical, are widely spread in nature, associated with water, soil, and vegetation. Usually, they are opportunistic pathogens with variable degrees of virulence. The outbreak of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) has changed their epidemiology. Between 25% and 50% of AIDS patients in Europe are infected with atypical mycobacteria resulting in disseminated disease (1).These organisms are acid-fast, like other mycobacteria, but their culture characteristics are different and many are resistant to streptomycin and isoniazid (2,3). They may not induce formation of granulomas and, under normal conditions, are not pathogenic for humans. Runyon’s detailed classification, according to growth rate and pigment production, includes such types as Mycobacterium marinum, M. fortuitum, M. kansasii, M. scrofulaceum, and others (4). Mycobacterium fortuitum has emerged lately as an associated pathogen in AIDS patients (5,6). It is a thin, branching bacillus seen in areas of suppuration and staining variably with Gram, auramine, Ziehl-Neelsen and, Fite stains (5). To date, about 80 mycobacterial species have been described (1). Mycobacterium avium and M. intracellulare have emerged as major pathogens for persons with AIDS and are described separately in Chapter 23, Part B.

Pathogenesis

In contrast to tuberculosis, the atypical mycobacteria, although infectious, are not communicable (4). They have been recognized as a cause of chronic lymphadenitis in children. In a study of 36 lymph node biopsies in children, atypical mycobacteria were recovered by culture, and bacilli were identified in tissues through acid-fast staining (7). A review of 30 cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections showed that 18 involved children and 10 cases involved patients with immunosuppression or hematologic diseases (8). Swimming-pool granulomas caused by M. marinum and localized cervical lymphadenopathies caused by various other atypical mycobacteria have been reported in children (9). Mycobacterium kansasii is known to cause cervical lymph node infections in children. These are more often submandibular, unilateral, and associated with erythema and abscess formation (3). In adults, nontuberculous mycobacterial infections have occurred in patients whose immunity has been iatrogenically suppressed for the treatment of malignant disease or the prevention of organ transplant rejection (8). Infections due to nontuberculous mycobacteria have been reported in kidney, heart, and liver transplant recipients (10). Mycobacterium kansasii, M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, and M. marinum produced nodular lesions more often in the skin and the lung, which more often remained localized, involving lymph nodes when the infection was able to disseminate. In patients with hairy cell leukemia, atypical mycobacterial infections have been reported in 9% to 25% of cases; the prevalence is higher than that for any other malignancy, possibly because of the monocyte deficiency associated with this neoplasm (11). The mycobacterium most often reported in infections complicating hairy cell leukemia is M. kansasii involving the lymph nodes and the lungs (12). In a report from Galveston, Texas, lymphadenitis with M. fortuitum was diagnosed in 11 AIDS patients: nine had cervical lymphadenitis and two disseminated lymph node lesions (5).

Histopathology

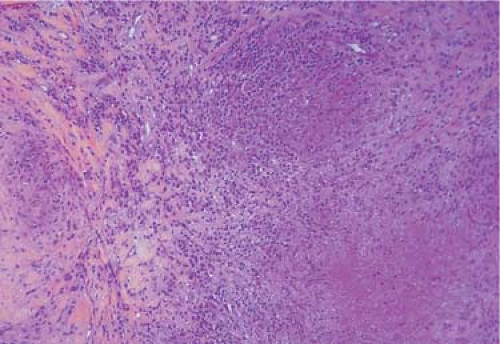

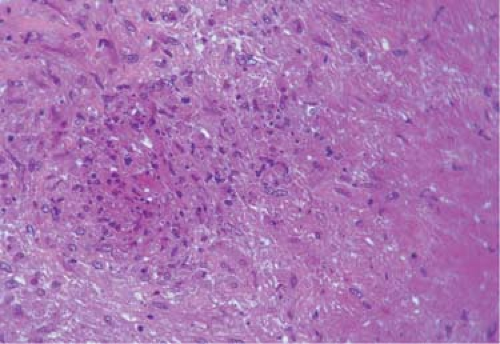

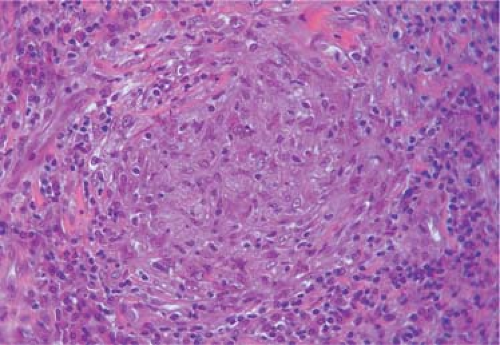

The lymph node lesions caused by atypical mycobacteria tend to be highly suppurative, particularly in children (3). In some cases, the histologic changes may be indistinguishable from those of tuberculosis, but in others a dimorphic pattern, composed of coexistent suppurative and granulomatous inflammation without caseation, was described (7). (Figs. 23A.1,23A.2,23A.3). It is generally believed that lesions are more acute and more exudative and contain larger amounts of acid-fast bacilli in atypical than in typical tuberculosis. This probably reflects the immunodeficiency of the host rather than the virulence of the pathogens. The presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the necrotic tissues does not indicate a secondary infection and appears to be part of the inflammatory response (7). Mycobacterium scrofulaceum in children or immunocompetent hosts causes mainly cervical lymphadenitis (1). In AIDS patients, it may produce lymphadenitis with large histiocytes filled with bacilli similar to lepromatous leprosy, indicative in both diseases of deficiencies in the T cell–macrophage interaction (13). Mycobacterium fortuitum in AIDS patients results in suppurative lymphadenitis with necrosis or mixed suppurative-granulomatous lymphadenitis (5).

Differential Diagnosis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis lymphadenitis exhibits fewer organisms, more organized granulomas. Definitive diagnosis is possible only by culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Figure 23A.1. Paratuberculosis lymphadenitis. Cervical lymph node in a 6-year-old child. Loose granuloma with necrosis. Hematoxylin, phloxine, and saffron stain. |

Figure 23A.2. Same section. Poorly formed granuloma with spindle-shaped histiocytes, lymphocytes and few neutrophiles. Hematoxylin, phloxine, and saffron stain. |

Figure 23A.3. Same section. Granuloma poorly formed, lack of typical epithelioid cells and giant cells. Hematoxylin, phloxine, and saffron stain. |

Checklist

Atypical Mycobacterial Lymphadenitides

Children or immunosuppressed adults

Acute exudative inflammation

Necrosis

Dimorphic (suppurative + granulomatous) pattern

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes in areas of necrosis

Abundant acid-fast bacilli

References

1. Adle-Biasette H, Huerre M, Breton G, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Ann Pathol 2003;23:216–235.

2. Karlson AG. Mycobacteria of surgical interest. Surg Clin North Am 1973;53:905–917.

3. Milliard M. Tuberculosis. In: Anderson WAD, Kissane JM, eds. Pathology, vol. 2. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1977;1107–1124.

4. Wolinsky E. Nontuberculous mycobacteria and associated diseases. Am Rev Respir Dis 1979;119:107.

5. Smith MB, Schnadig VJ, Boyars MC, et al. Clinical and pathologic features with Mycobacterium fortuitum infections. An emerging pathogen in patients with AIDS. Am J Clin Pathol 2001;16:225–232.

6. Mederos LM, Gonzalez D, Banderas F, et al. Ulcerative lymphadenitis due to Mycobacterium fortuitum in an AIDS patient. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2005;23:573–574.

7. Reid JD, Wolinsky E. Histopathology of lymphadenitis caused by atypical mycobacteria. Am Rev Respir Dis 1969;99:8–12.

8. Chester AC, Winn WC Jr. Unusual and newly recognized patterns of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection with emphasis on the immunocompromised host. Pathol Annu 1986;21:251–271.

9. Lincoln EM, Gilbert LA. Disease in children due to mycobacterium other than Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1972;105:683.

10. Patel R, Roberts GD, Keating MR, et al. Infections due to nontuberculous mycobacteria in kidney, heart and liver transplant recipients. CID 1994;19:263–273.

11. Weinstein RA, Golomb HM, Grumet G. Hairy cell leukemia: association with disseminated atypical mycobacterial infection. Cancer 1981;48:380–383.

12. McLoud TC, Harris NL. Case record 52. 1982. N Engl J Med 1982;307:1693–1700.

13. Delabie J. De Wolf-Peeters C, Bobbaers H, et al. Immunotypic analysis of histiocytes involved in AIDS-associated mycobacterium scrofulaceum infection: similarities with lepromatous lepra. Clin Exp Immunol 1991;85:214–218.

B. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare Lymphadenitis

Definition

Lymphadenitis caused by Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAI).

Synonym

MAI lymphadenitis.

Epidemiology

Mycobacteriosis, the disseminated MAI infection, is very rarely seen in normal people. In transplant patients, although the incidence is low, it far exceeds that in the healthy population. In transplant recipients, 25% to 40% of mycobacterial infections are caused by nontuberculous strains, as compared with 5% to 10% of these infections in the general population. These

patients also experience a greater proportion of extrapulmonary disease (1). In patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), mycobacteriosis has emerged as one of the most critical life-threatening opportunistic infections, with high morbidity and mortality (2,3). In the United States, in the early 1990s, MAI was the most commonly reported bacterial infection in people with AIDS and could be isolated from the blood in 40% to 60% of those who had survived 2 years (4,5). Since the introduction of the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of MAI has markedly fallen among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected people (5). Decreases of MAI in HIV+ individuals from 11.6% to 4.4% in a French study (6) and from 30% to 2% in an American study (7) were recorded after the introduction of protease inhibitor treatment in 1996. Children with AIDS are particularly susceptible to MAI infection and lymphadenitis, from the report of an 8-month-old infant in India to a series of 56 pediatric patients studied in Boston (8,9).

patients also experience a greater proportion of extrapulmonary disease (1). In patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), mycobacteriosis has emerged as one of the most critical life-threatening opportunistic infections, with high morbidity and mortality (2,3). In the United States, in the early 1990s, MAI was the most commonly reported bacterial infection in people with AIDS and could be isolated from the blood in 40% to 60% of those who had survived 2 years (4,5). Since the introduction of the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of MAI has markedly fallen among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected people (5). Decreases of MAI in HIV+ individuals from 11.6% to 4.4% in a French study (6) and from 30% to 2% in an American study (7) were recorded after the introduction of protease inhibitor treatment in 1996. Children with AIDS are particularly susceptible to MAI infection and lymphadenitis, from the report of an 8-month-old infant in India to a series of 56 pediatric patients studied in Boston (8,9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree