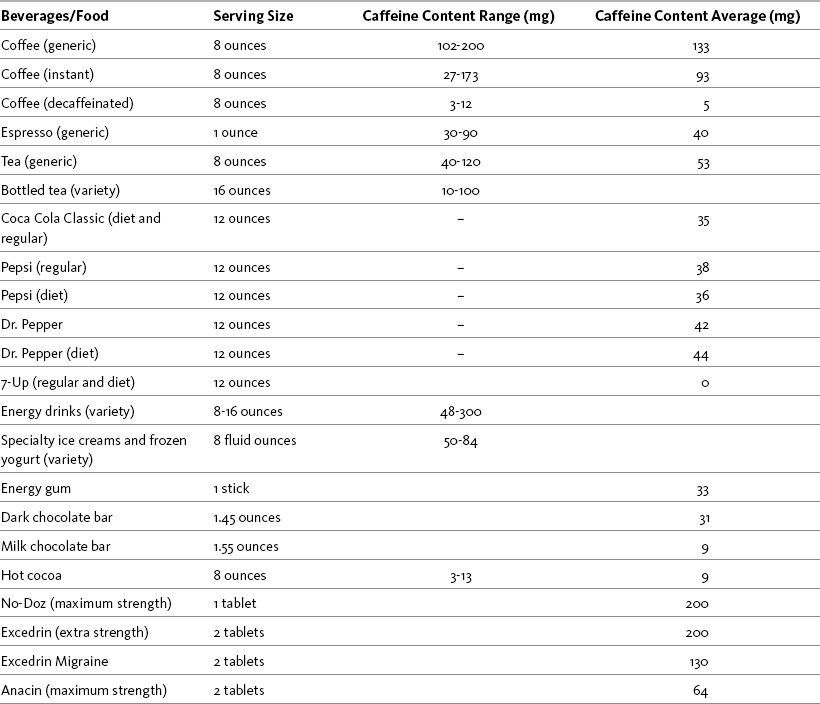

Chapter 9 Many nonprescription pain relievers are merely different doses of either acetaminophen or aspirin. Quite a few contain both aspirin and acetaminophen. The combination of acetaminophen and aspirin has raised concern about enhanced renal toxicity, and some find this combination questionable. Other common ingredients in nonprescription pain relievers are buffering agents, caffeine, and antihistamines. (See Patient Medication Information Forms III-4 and III-5 on pp. 256-259). Caffeine has been used to augment pain relief since research in the early 1980s showed that it produced a 40% acetaminophen dose-sparing effect (Zhang, 2001). Other research found that caffeine in combination with acetaminophen (but not alone) produced a significant enhanced and prolonged analgesic effect with onset of analgesia within 30 minutes and lasting for up to 3 hours (Renner, Clarke, Grattan, et al., 2007). Caffeine produces a synergistic effect with a variety of other analgesics as well, including opioids and NSAIDs (Diamond, Freitag, 2001; Mitchell, van Zanten, Inglis, et al., 2008). Consumption of caffeinated coffee has even been found to enhance the analgesic effect of nicotine (Nastase, Ioan, Braga, et al., 2007) (see Section V for more on nicotine analgesia). The underlying mechanisms of caffeine’s action are unclear, but theories include that it blocks adenosine receptors, inhibits COX-2, or simply changes emotional state (Zhang, 2001). A randomized controlled study found that a single dose (2 tablets) of the combination of aspirin (250 mg), acetaminophen (250 mg), and caffeine (65 mg) produced significantly better and faster pain relief than a single dose of ibuprofen (200 mg) or placebo for acute migraine (Goldstein, Silberstein, Saper, et al., 2006). In contrast, a study of patients following outpatient general surgery found that acetaminophen plus ibuprofen produced fewer adverse effects and higher patient satisfaction than the combination of acetaminophen, codeine, and caffeine (Mitchell, van Zanten, Inglis, et al., 2008). However, the difference in findings in this study may have been due to codeine, which is associated with a relatively high incidence of adverse effects and wide variability in efficacy due to dependence on CYP2D6 metabolism; 10% of Caucasians are poor metabolizers and derive little or no analgesia from codeine (Stamer, Stuber, 2006) (see Chapter 13 for more on codeine). Other research supports the use of caffeine in the postoperative setting; randomized-controlled trials and an extensive meta-analysis of 30 trials concluded that caffeine significantly enhanced postoperative pain relief when combined with other analgesics (Fitzgerald, Buggy, 2006). Despite this evidence, caffeine is rarely prescribed as a component of a postoperative multimodal analgesic regimen. IV caffeine has been researched in advanced cancer patients experiencing adverse psychomotor effects associated with high doses of opioids and found to have little effect (Mercandante, Serretta, Casuccio, 2001). Pain significantly decreased, but this was not statistically superior to placebo. Caffeine produced improvements in speed of finger tapping, but there was no improvement in cognitive outcomes as measured by testing of visual memory and number and digit recall. (See Section V for use of caffeine to counteract opioid-induced sedation.) A variety of food products contain caffeine. Chocolate lovers may be dismayed to learn that most chocolate contains very little caffeine (e.g., 9 mg). However, 1.45 ounces of dark, semisweet chocolate contains 31 mg, requiring at least 3 ounces to obtain the desired analgesic effect. The popularity of energy drinks, which contain large amounts of caffeine (e.g., 300 mg), has prompted calls for changes in labeling to include stronger warnings of the dangers of excessive caffeine intake (Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2008). See Table 9-1 for the caffeine content of common beverages, food, and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. Table 9-1 Content of Caffeine in Selected Beverages, Food, and OTC Drugs From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 241, St. Louis, Mosby. Data from Center for Science in the Public Interest. Available at http://www.cspinet.org/new/cafchart.htm. Accessed December 24, 2008; Energy fiend. Available at http://www.energyfiend.com/the-caffeine-database. Accessed December 24, 2008. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

Nonprescription Nonopioids

Caffeine

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree