Hepatotropic viruses

Nonhepatotropic viruses

Viruses that preferentially and predominantly infect liver

Viruses that involve the liver as part of systemic or multiorgan infection

Hepatitis viruses A, B, C, E, and delta agent

Cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, herpes virus, adenovirus, human immunodeficiency virus

Can cause acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, or acute liver failure

Usually cause acute hepatitis or acute liver failure

Affect immunocompetent individuals

Usually affect immunocompromised individuals

Hepatotropic viruses preferentially and predominantly affect the liver, while nonhepatotropic viruses affect the liver as part of a systemic or multiorgan infection

The hepatotropic viruses include hepatitis A, B, C, E, and the delta agent

The most common nonhepatotropic viruses affecting the liver are cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), herpesvirus, and adenovirus

♦

The clinical syndromes caused by viral hepatitis include acute viral hepatitis, acute liver failure also known as fulminant hepatic failure, and chronic hepatitis

♦

Acute hepatitis may resolve spontaneously (self-limited hepatitis) or progress to chronic liver disease

In a minority of cases, acute viral hepatitis may progress to acute liver failure

Progression of acute to chronic hepatitis occurs with infection by hepatotropic viruses and is not seen with infection by nonhepatotropic viruses

♦

Chronic liver disease is progressive, but the rate of progression is variable

♦

The factors underlying this variability are not accurately defined but include both host and viral factors

♦

Acute hepatitis is characterized microscopically by lobular changes that overshadow the changes in the portal tracts or are at least as severe as those in the portal tracts

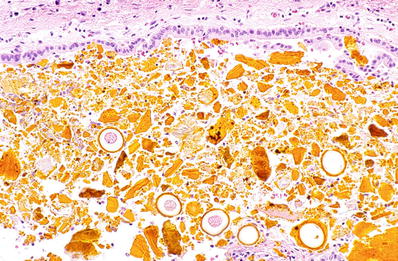

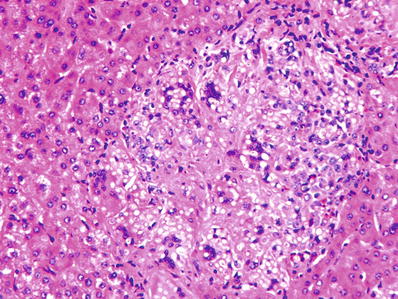

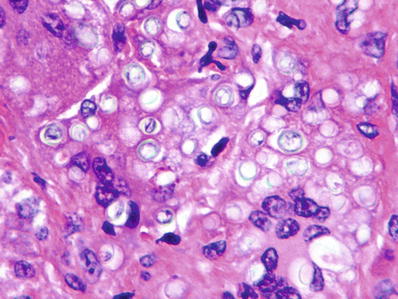

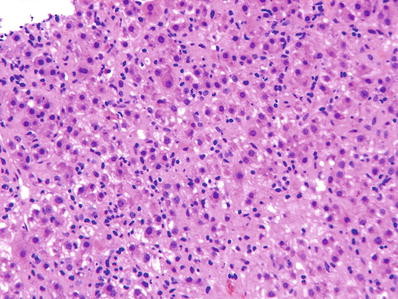

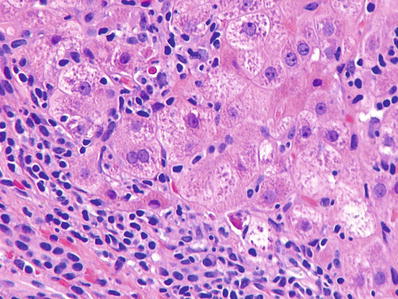

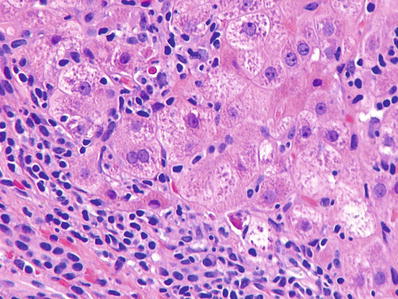

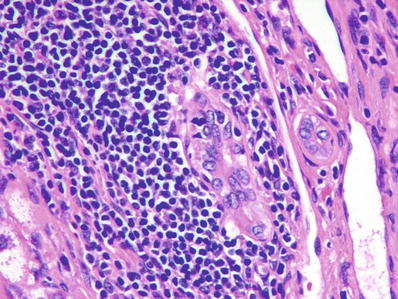

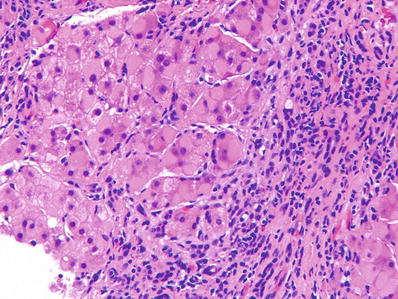

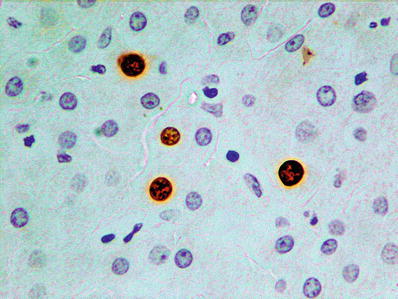

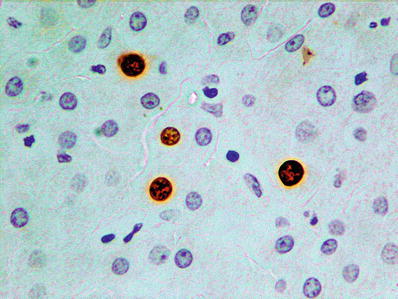

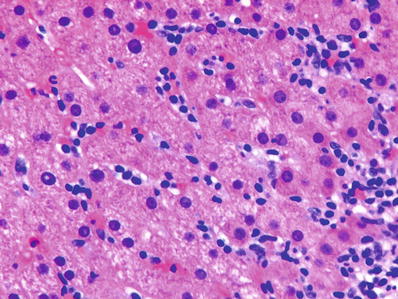

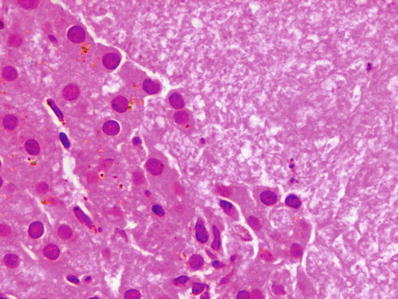

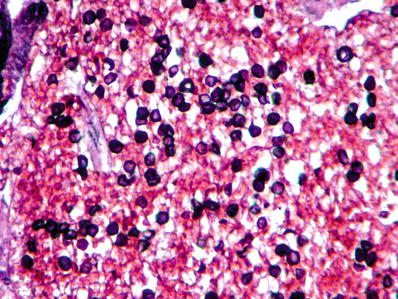

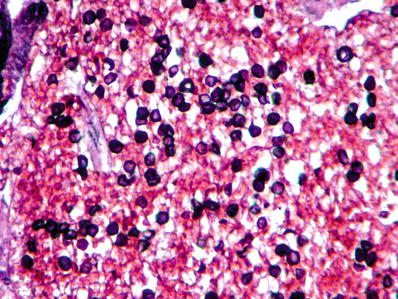

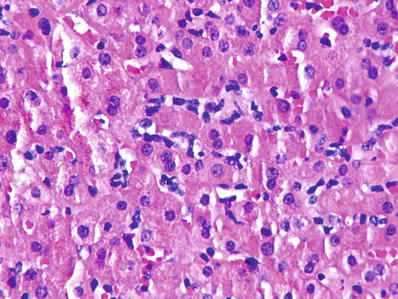

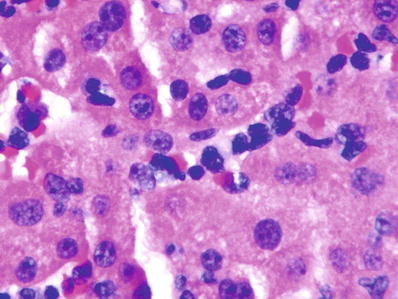

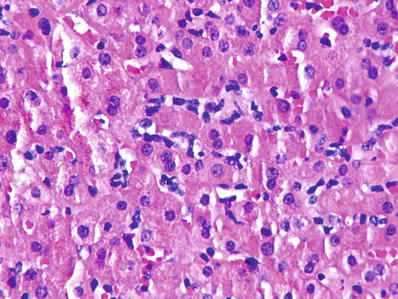

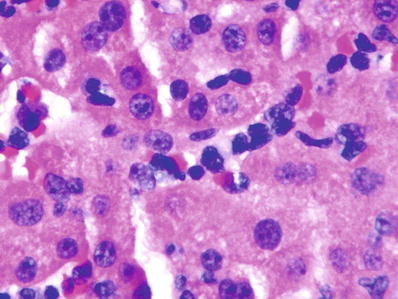

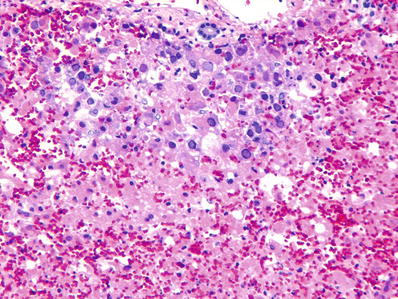

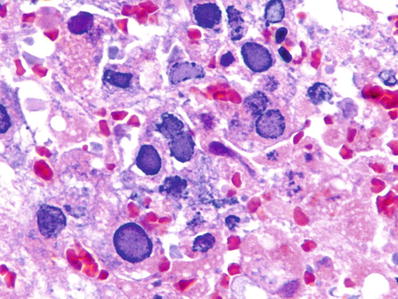

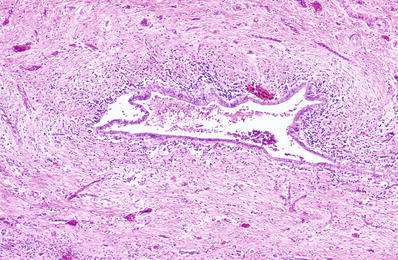

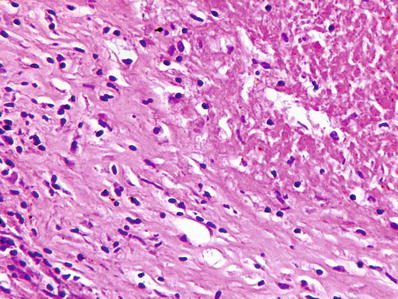

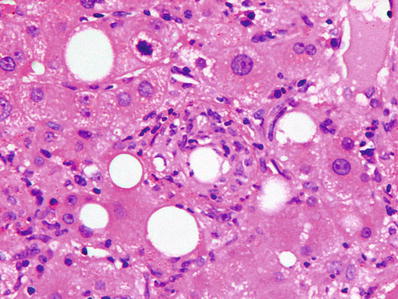

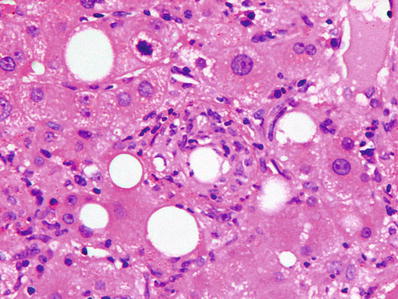

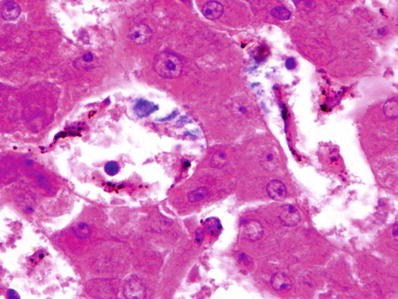

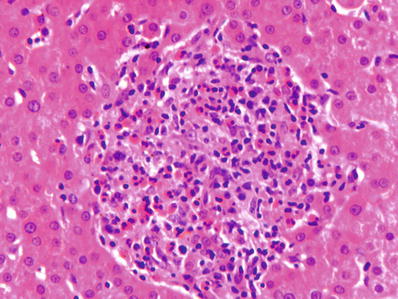

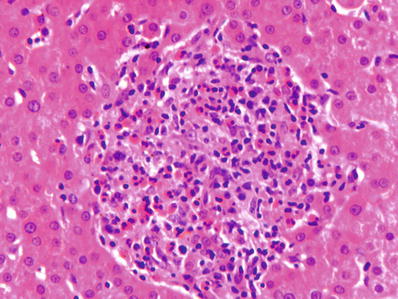

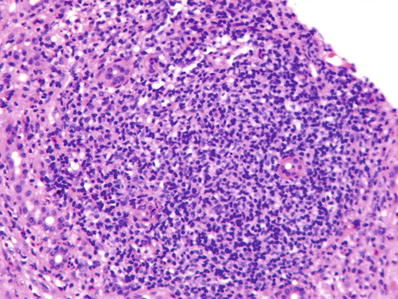

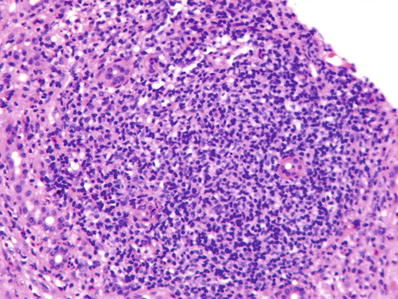

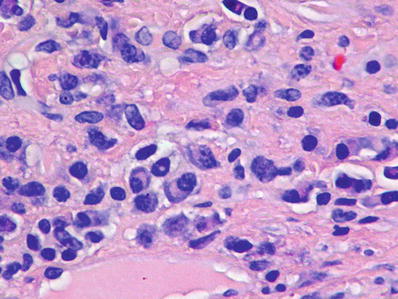

The lobular changes in acute hepatitis are characterized by lobular inflammation, necrosis, apoptotic bodies, hepatocyte degeneration, and Kupffer cell prominence giving an appearance of “lobular disarray” (Figs. 44.1, 44.2, 44.3, and 44.4)

Fig. 44.1.

Acute hepatitis showing “lobular disarray” caused by lobular inflammation, Kupffer cell prominence, cell degeneration, and necrosis.

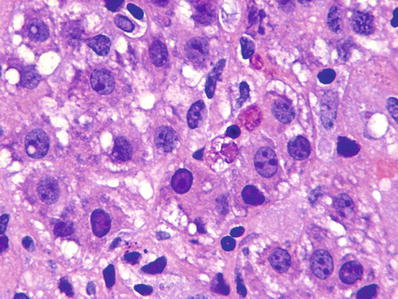

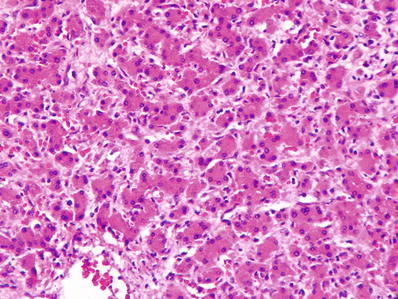

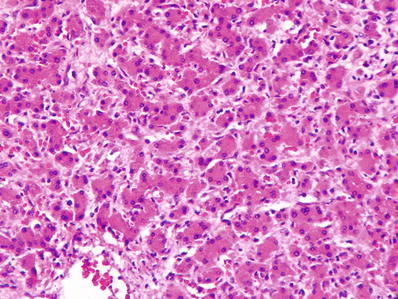

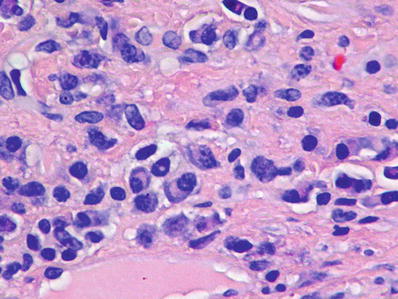

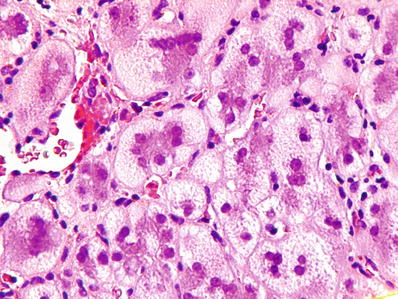

Fig. 44.2.

Acute hepatitis showing cellular degeneration and apoptotic bodies.

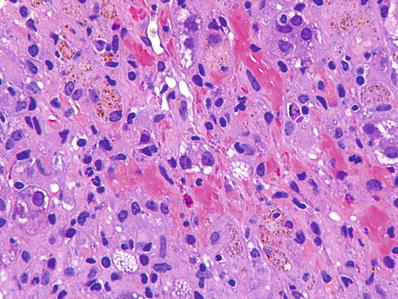

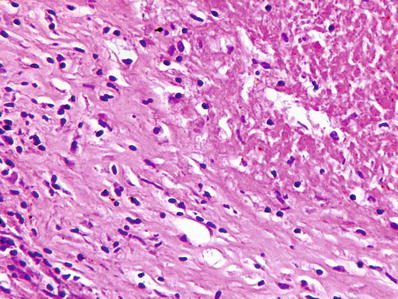

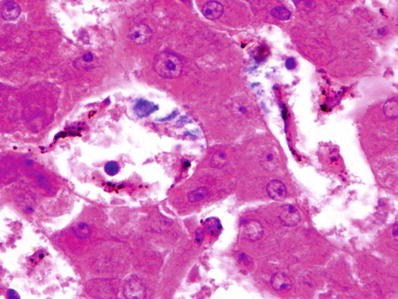

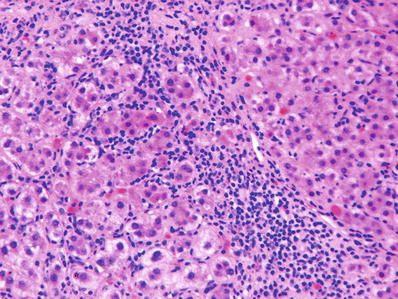

Fig. 44.3.

Acute hepatitis with areas of parenchymal collapse containing pigment-laden macrophages.

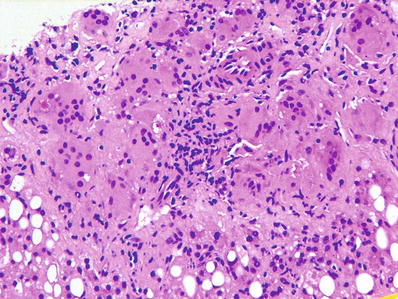

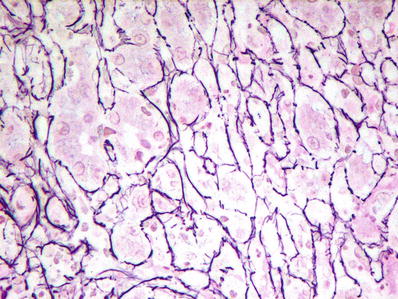

Fig. 44.4.

Reticulin stain in acute hepatitis showing collapse of hepatic plates.

Portal inflammation may be present to a variable degree but is overshadowed by lobular changes

All causes of acute hepatitis show similar features

Therefore, the differential diagnosis of acute viral hepatitis includes other causes of acute hepatitis such as drug-induced hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis

Diagnosis is established by correlation with serological and clinical findings

♦

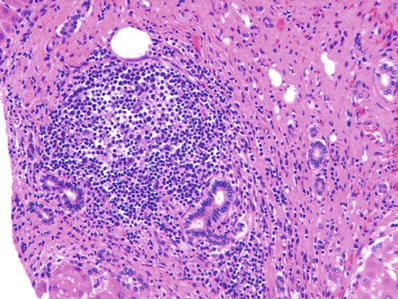

Chronic hepatitis is characterized by portal inflammation and progressive destruction of hepatocytes present at the interface with portal tracts. This is also called interface hepatitis or piecemeal necrosis; the former term is preferred (Fig. 44.5)

Fig. 44.5.

Chronic hepatitis showing interface hepatitis (piecemeal necrosis) with a mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate destroying hepatocytes at the limiting plate. Several necrotic hepatocytes are seen surrounded by lymphocytes.

Lobular inflammation and damage are present in variable degrees but are not the predominant finding

Determination of the cause of chronic hepatitis requires knowledge of clinical and serological data as all hepatotropic viruses show similar histological findings; the exceptions to this are as follows:

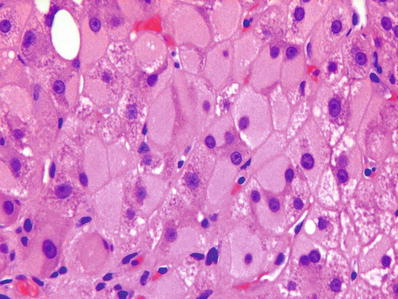

The presence of ground glass cells in hepatitis B (Fig. 44.6)

Immunohistochemical positivity with specific antibodies against the hepatitis B surface and core antigens or the delta agent

Fig. 44.6.

Ground glass hepatocytes in chronic hepatitis B infection. The ground glass appearance results from the accumulation of surface antigen in endoplasmic reticulum.

♦

The presence of a triad of mild bile duct destruction, mild fatty change, and portal lymphoid follicles/aggregates in chronic hepatitis C infection (Figs. 44.7 and 44.8)

Portal lymphoid aggregates may also be present in a host of other chronic liver diseases such as autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and chronic hepatitis B infection

No specific immunohistochemical stains are available for the diagnosis of hepatitis C infection

Fig. 44.7.

Chronic hepatitis C infection showing a portal lymphoid follicle.

Fig. 44.8.

Chronic hepatitis C infection showing epithelial damage of bile duct, which is surrounded by lymphoid aggregate.

Grading and Staging of Viral Hepatitis (Table 44.2)

Table 44.2.

Grading and Staging of Chronic Viral Hepatitis

Grading | Staging |

|---|---|

Determines aggressiveness of hepatitis | Determines the progression of hepatitis along the path to cirrhosis |

Assessed by: | Assessed by degree of fibrosis |

Lobular inflammation and damage Inflammation and damage at interface of portal tracts with hepatocytes (“limiting plate”) | |

Systems with numeric values: | Systems with numeric values: |

Semiquantitative | Four-stage systems (commonly used; see Table 44.3) Six-stage system of Ishak |

Systems with descriptive terms (none, minimal, mild, moderate, severe) |

♦

The grade of hepatitis indicates the “aggressiveness” of the disease process which is reflected by the degree of inflammatory activity, whereas the stage of hepatitis refers to the “progression” of disease as determined by the degree of fibrosis

Stage indicates how far the disease has progressed along the path to cirrhosis

♦

The grade of hepatitis, i.e., inflammatory activity, is determined by:

The degree of lobular inflammation and damage

The degree of interface hepatitis which is inflammation and damage of hepatocytes at the interface with portal tracts (Fig. 44.9)

Fig. 44.9.

Severe interface hepatitis in chronic hepatitis B infection; interface hepatitis was seen around the entire circumference of all portal tracts. Note the ground glass cells.

The synonymous term “piecemeal necrosis” is no longer favored

♦

Several semiquantitative, numeric grading systems exist, but the most practical one is a grading system using descriptive terms such as “none, minimal, mild, moderate, and severe”

The older system of chronic persistent hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis, and chronic lobular hepatitis is no longer in use

♦

A more detailed system called the histological activity index (HAI) was devised by Knodell et al

A numerical and highly complex schema, the Knodell score is best suited for clinical trials, which require statistical analysis of complex data in large cohorts of patients

♦

Stage of chronic hepatitis is determined by the degree of fibrosis

Accurate staging requires a connective tissue stain such as the Masson trichrome stain

There are several staging systems; all but the Ishak system comprise four stages

The Ishak system comprises six stages and provides greater discriminatory value

The four staging systems currently used in clinical practice are shown in Table 44.3. The Batts and Ludwig is a modification of the Scheuer system. The Ishak system is a modification of the HAI

Table 44.3

Commonly Used Staging Systems

Stage 0

Stage 1

Stage 2

Stage 3

Stage 4

Scheuer

No fibrosis

Enlarged portal tracts

Periportal fibrosis or portal–portal septa

Fibrosis with architectural distortion but no cirrhosis

Cirrhosis

Batts and Ludwig

No fibrosis

Portal fibrosis distortion

Portal fibrosis with rare portal–portal septa

Septal fibrosis with architectural distortion

Cirrhosis

Bedossa and Poynard (METAVIR)

No fibrosis

Portal fibrosis

Portal fibrosis with rare septa

Numerous septa without cirrhosis

Cirrhosis

Stage 0

Stage 1

Stage 2

Stage 3

Stage 4

Stage 5

Stage 6

Ishak

No fibrosis

Some enlarged portal tracts with or without short septa

Many enlarged portal tracts with or without short septa

Many enlarged portal tracts with occasional portal–portal bridging

Marked bridging fibrosis

Incomplete cirrhosis

Cirrhosis

Hepatitis A

Clinical

♦

Hepatitis A virus is a 27 nm icosahedral, nonenveloped, single-stranded RNA picornavirus that is transmitted by the fecal–oral route

♦

Hepatitis A infection is endemic in hot, tropical countries with poor sanitation and overcrowding

♦

The incubation period of the virus is approximately 4–6 weeks

♦

Most patients develop an acute, self-limited hepatitis

The virus may rarely cause acute liver failure and is responsible for fatality in <0.1% of cases

The virus does not cause a chronic carrier state or chronic liver disease

♦

Antibodies appear in serum following the incubation period

The first to appear is anti-HAV IgM followed by anti-HAV IgG

Anti-HAV IgM may persist in serum for as long as 1 year, and its presence indicates recent infection

Anti-HAV IgG imparts lifelong immunity against reinfection, and its presence indicates remote exposure

Microscopic

♦

The microscopic features are as those described for acute hepatitis

♦

Plasma cells predominate in the inflammatory infiltrate, which involves portal, periportal, and lobular areas

♦

Some cases show a predominantly cholestatic clinical picture with marked centrilobular cholestasis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

All causes of acute hepatitis including autoimmune and drug-induced hepatitis

♦

Hepatitis E infection has a clinical profile and endemicity similar to hepatitis A infection

Hepatitis B

Clinical

♦

Hepatitis B virus is a 42 nm enveloped particle with an inner hexagonal core containing a circular double-stranded DNA genome

♦

Hepatitis B is the most common viral hepatitis worldwide

It is endemic in parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America

♦

The virus is transmitted by exposure to contaminated blood and body fluids

The modes of transmission include transfusions, sexual contact, and the use of contaminated needles and syringes

In highly endemic areas, such as parts of Asia, the virus is transmitted through the placenta from mother to fetus. This is called vertical transmission

Infection acquired vertically from mother to fetus usually leads to a chronic carrier state

♦

Active immunization is successful in preventing the disease

♦

Most cases of hepatitis B infection are subclinical

Approximately 10% progress to acute liver failure or chronic liver disease

The risk factors for progression to chronic liver disease are not entirely known, but host factors appear to play a major role

♦

Following infection, t he hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) appears first in serum, followed by HBeAg

These are followed by the appearance of anti-HBc IgM and anti-HBe

The HBsAg is lost after approximately 2 months, and anti-HBs appears in the blood after a 1- to 4-month window period

Persistence of HBeAg indicates persistent infection and the likelihood of progression to chronic hepatitis

♦

The virus is not directly cytopathic but causes liver damage secondary to immune-mediated injury

An exception is fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis, a rapidly progressive form of recurrent hepatitis B which occurs following transplantation

Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis is a direct cytopathic effect of rapid intracellular proliferation of the virus in these immunosuppressed patients

Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis has been virtually eliminated by the routine administration of hepatitis B immune globulin and lamivudine in patients transplanted for hepatitis B infection

♦

There is a high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma even in the absence of significant inflammation or fibrosis

Microscopic (Acute Hepatitis B)

♦

Acute hepatitis B is marked by lobular-predominant inflammation with varying degrees of hepatocellular degeneration, ballooning, necrosis, and regenerative changes

♦

A mononuclear portal inflammatory infiltrate is also present

♦

The number of ground glass hepatoc ytes is inversely proportional to the degree of inflammation

Ground glass cells represent an admixture of cytoplasmic aggregates of HBsAg and smooth endoplasmic reticulin, which distend the cytoplasm and displace the nucleus to the periphery

The ground glass change appears as a cytoplasmic inclusion and is usually surrounded by a clear halo

Microscopic (Chronic Hepatitis B)

♦

The microscopic appearance of chronic hepatitis B shows varying degrees of portal mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate accompanied by varying degrees of periportal inflammation with destruction of the limiting plate

This is accompanied by variable lobular inflammation and damage, which is inversely proportional to the number of ground glass hepatocytes

♦

Carriers of the disease show numerous ground glass hepatocytes without any accompanying inflammation

♦

In contrast to hepatitis C, steatosis is not a feature of chronic hepatitis B infection

When present, alcoholic or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease should be ruled out

♦

Varying degrees of portal-based fibrosis are present

Special Studies

♦

Immunohistochemical stains for HBsAg and hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) are not uncommonly negative in acute hepatitis B especially in patients with an active hepatitis

These markers are often positive in chronic hepatitis B

The extent of positivity is inversely proportional to the degree of inflammation

♦

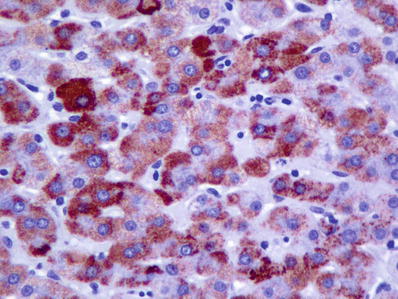

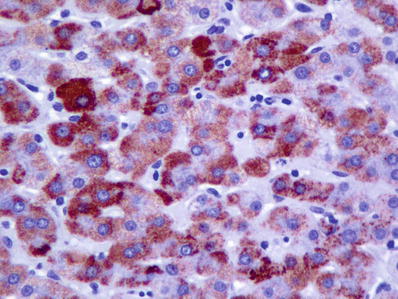

Immunohistochemical staining for HBsAg shows cytoplasmic positivity with or without HBcAg positivity (Fig. 44.10)

Fig. 44.10.

Immunohistochemical stain for hepatitis B surface antigen showing extensive cytoplasmic positivity.

The presence of membranous staining for HBsAg is an indirect evidence of active viral replication

♦

Immunohistochemical staining for HBcAg shows nuclear positivity and is indicative of active viral replication (Fig. 44.11)

Fig. 44.11.

Immunohistochemical stain for hepatitis B core antigen shows nuclear positivity and indicates active viral replication.

The presence of additional cytoplasmic positivity for core antigen indicates replication so active that excess core antigen spills from the nucleus into the cytoplasm

♦

Membranous positivity for HBsAg and cytoplasmic positivity for HBcAg are characteristic features of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis indicating brisk and unopposed viral replication in immunocompromised individuals

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other viral hepatitis

♦

Drug-induced hepatitis

♦

Autoimmune hepatitis

Hepatitis C

Clinical

♦

Hepatitis C virus is an enveloped single-stranded RNA flavivirus which is related to the viruses that cause dengue fever and yellow fever

♦

Hepatitis C viral infection is a global disease, albeit one with a wide range of prevalence rates

The prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies is 1.8% in the USA and 22% in Egypt

No effective v accine exists against hepatitis C infection

♦

The mode of transmission is blood-borne

Before its identification and initiation of routine screening of blood donors in 1991, hepatitis C virus was the major cause of posttransfusion non-A, non-B hepatitis

New infections in developed countries are now acquired through contaminated needles in intravenous drug abusers

Other means of transmission include acupuncture, tattooing, sharing razors, and needlestick injuries in healthcare workers

Less stringent precautions in t he healthcare setting may be responsible for infections

Sexual and transplacental infections are responsible for a minority of cases

♦

Six major genotypes with 40 subtypes are known to exist

An individual patient may harbor several subtypes (quasispecies)

Genotypes 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, and 3a are common in Western Europe and the USA

Genotype 4 is common in Africa and the Middle East

♦

The incubation period is 6–7 weeks; acute infection is subclinical and asymptomatic in 90% of cases

T he majority of infected individuals are, however, unable to clear the virus due to the rapid generation of quasispecies, which escape the body’s immune responses

♦

Most patients pursue a relatively indolent course over many years

The major clinical manifestations include significant fatigue (50% at 10 years), cirrhosis (25% at 20 years), and hepatocellular carcinoma (5% at 30 years)

♦

Diagnosis of hepatitis C infection is established by detecting antibodies by an enzyme immunoassay with subsequent confirmation by recombinant immunoblot assay

♦

Treatment of HCV infection has evolved very rapidly in recent years from pegylated interferon and ribavirin based therapy to combination therapy with oral direct-acting agents (DAA)

The first FDA-approved DAAs (telaprevir and boceprevir) were first introduced in 2011 and had to be combined with interferon and ribavirin

They increased sustained virologic response (SVR) rates from 30–40% to approximately 75% in genotype 1 disease

♦

Subsequent FDA-approved agents included sofosbuvir (a nucleoside NS5B inhibitor with pan-genotypic efficacy) and simeprevir (an NS3/NS4A protease inhibitor for genotype 1 disease), which were recommended for combination use with interferon and ribavirin in genotype 1 disease

Sofosbuvir could be used with ribavirin alone in genotype 2 and 3 or in genotype 1 cases with contraindication/intolerance to interferon

These two agents also offered the first interferon- and ribavirin-free option for oral-only therapy of HCV with SVR rates >90% in clinical trials and >80% in clinical experience

♦

Most recently, oral-only therapy, with or without ribavirin, has been FDA approved for pan-genotypic infection (single combination pill of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir) or genotype 1 disease (combo pack of ombitasvir/ritonivir/ paritaprevir/dasabuvir)

These therapies have been associated with 90–100% SVR rates and have been shown to be highly effective even in patients with cirrhotic stage disease, with only limited data in patients with compensated cirrhosis

These therapies are also effective in the treatment of HCV recurrence following liver transplantation

♦

Cirrhosis due to chronic HCV infection is the leading cause for liver transplantation in the USA

Hepatitis C infection rec urs in the allograft

The rate of progression is highly variable

The factors underlying this variability are poorly understood

Microscopic (Acute Hepatitis C)

♦

Acute hepatitis C is rarely biopsied

The histology of acute hepatitis C is best seen when the liver allograft is biopsied for the diagnosis of recurrent hepatitis C infection

♦

The features are those of acute hepatitis with lobular inflammation, hepatocyte damage, and disarray

Confluent and bridging necrosis is rare

♦

Significant portal inflammation and lymphoid aggregates are common

♦

The overall picture is similar to chronic hepatitis C; however, fibrosis is absent

Microscopic (Chronic Hepatitis C)

♦

There is prominent portal and periportal inflammation consisting mainly of lymphocytes

♦

Lymphoid aggregates and follicles are typically present

These are not specific for hepatitis C infection and also occur in hepatitis B infection, autoimmune hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis

♦

Mild and focal bile duct damage is seen in a significant number of cases

Progressive bile duct damage a nd ductopenia do not occur

♦

Macrovesicular steatosis usually occurs and is generally mild and nonzonal

♦

Lymphocytic interface hepatitis, lobular inflammation, and hepatocellular necrosis define disease activity (grade)

These changes are common but usually mild

A distinctive pattern is the presence of sinusoidal lymphocytes and macrophages (“string of beads”) (Fig. 44.12)

Fig. 44.12.

Chronic hepatitis C infection showing sinusoidal lymphocytosis, the so-called “string of beads” appearance.

♦

Grading continues to be important in assessing disease activit y because other reliable surrogate markers are not available

Grading also plays a role in the assessment of prognosis and predicting response to therapy

♦

Stage predicts time to the development of cirrhosis, response to medical therapy, rate of disease progression in untreated patients, and efficacy of therapy

Special Studies

♦

Reliable immunohistochemical and/or in situ hybridization methods are not available for tissue diagnosis of HCV

♦

HCV RNA levels and HCV genotype help predict and assess response to therapy

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other viral hepatitis

♦

Drug-induced hepatitis

♦

Autoimmune hepa titis

Hepatitis D

♦

Hepatitis D virus, also called the delta agent , is a small RNA virus that requires the presence of the hepatitis B virus for replication and infection

Approximately 5% of patients with hepatitis B virus infection are also infected with the hepatitis delta agent

♦

Hepatitis D infection increases the severity of acute and chronic HBV infection and decreases the likelihood of becoming an HBV carrier

♦

The virus has a worldwide distribution, albeit one with significant geographic variation in prevalence

The prevalence is highest in South America

High prevalence is also present in southern Italy, North Africa, Middle East, and the American South Pacific islands

♦

The virus is transmitted parenterally through contaminated needles and blood transfusions

Sexual and vertical transmissions also occur but are less common than for hepatitis B virus

♦

HDV infection may occur simultaneously with hepatitis B infection (coinfection) or sequentially in a patient who is already infected with the hepatitis B virus (superinfection)

♦

Coinfection results in clearance of both viruses in the majority of patients

Fulminant hepatic failure occurs in 1% and chronic hepatitis B and D in 5% of coinfected individuals

♦

Superinfection of hepatitis B infection with hepatitis D virus results in fulminant liver failure in 5% of individuals

80–90% of individuals develop chronic hepatitis D infection

These patients progress faster to cirrhosis

♦

Microscopic features are similar to those of hepatitis B viral infection

♦

Diagnosis is made by serologic testing or RT-PCR which is the method of choice

♦

Treatment is based on interferon but is of uncertain benefit

Antiviral drugs used for the treatment of hepatitis B infection are not effective

♦

Liver transplantation is a valid treatment option; the risk of allograft reinfection is much less than that for chronic hepatitis B infection

Hepatitis E

Clinical

♦

Hepatitis E is a single-stranded RNA virus (family, Hepeviridae; genus, Hepevirus)

♦

Genotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4 infect humans

♦

Genotypes 1 and 2 are transmitted by the fecal–oral route through contaminated water

Genotype 1 is endemic in Asia and genotype 2 in Africa and Mexico

♦

Genotypes 3 and 4 are transmitted by eating undercooked or raw meats, mainly pork and wild game

These are zoonotic infections; animal reservoirs include pigs, deer, and wild boar

Genotype 3 is endemic in the USA and Europe, whereas genotype 4 is endemic in Asia

There is higher incidence of seropositivity in individuals who work in the pork processing industry

♦

Genotypes 1 and 2 infect children and young adults, whereas genotypes 3 and 4 infect older individuals (especially men over 50–60 years of age) and individuals immunocompromised due to solid organ transplantation, infection due to HIV, or chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies

♦

HEV causes an acute hepatitis in the majority of individuals which is clinically indistinguishable from hepatitis A

The incubation period is 15–60 days

A prodromal phase is followed by an icteric phase

The infection is self-limited in the majority of patients

The overall fatality rate is approximately 3–4%

The fatality rate in pregnant women is 20% and is associated with encephalopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation

♦

There is higher risk of prematurity and perinatal mortality

♦

HEV infection with genotype 3 in immunocompromised hosts may cause chronic hepatitis leading to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis

Extrahepatic manifestations including neuromuscular, kidney, and hematologic involvement may occur in immunosuppressed individuals infected with HEV

♦

HEV may cause acute hepatitis in patients with preexisting chronic liver disease

Patients with alcoholic liver disease are especially susceptible

This may lead to decompensation of cirrhosis and liver failure

♦

Microscopically, the features resemble acute hepatitis from other causes

Centrilobular cholestasis and gland-like transformation of hepatocytes (rosettes) may be seen

♦

Diagnosis is made by serologic testing for antibodies to HEV or by PCR for HEV RNA

Antibodies to HEV may be absent in immunocompromised hosts

♦

Treatment consists of ribavirin and reducing immuno-suppression

♦

Vaccines have been developed; one has been licensed for use in China

Vaccines may have a role for travelers to endemic areas and before solid organ transplantation

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

Clinical

♦

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a single-stranded RNA virus and a member of lentivirus (a subgroup of retrovirus)

♦

Liver function tests are abnormal in the majority of patients with HIV infection

This does not always correspond to liver disease

The liver may, however, be involved in patients infected with HIV through a variety of mechanisms, which include infection by HIV virus itself, secondary infections, neoplasms, and toxicity of drugs that are used to treat the HIV infection or associated infections and comorbidities

♦

As patients with HIV and AIDS live longer due to the efficacy of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), coinfections with hepatitis B and C viruses have emerged as major long-term hepatic comorbidities

Microscopic

♦

Infection of the liver by the HIV virus produces a pattern of reactivity characterized by minimal to mild portal inflammatory infiltrate, marked prominence of Kupffer cells, foci of lobular inflammation, and minimal degree of steatosis

The Kupffer cells show PAS-positive granules, which are resistant to enzyme digestion

♦

Ductular reaction, portal edema, and fibrosis may be seen in patients with end-stage AIDS who have infection of the biliary tree by cryptosporidium

Imaging in these cases shows features of sclerosing cholangitis

♦

Steatosis is a common finding in livers of patients with HIV infection

Steatosis may be due to a variety of underlying causes such as drug toxicity and comorbidities such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and chronic viral hepatitis

♦

Patients who are coinfected with hepatitis B or hepatitis C viruses show pathologic features characteristic of these hepatotropic viruses

♦

Patients with superimposed infections such as CMV, herpes, or toxoplasmosis show viral inclusions characteristic of these viruses

Herpes infections and toxoplasmosis produce punched-out areas of necrosis

♦

Granuloma s may be seen in patients who are infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. avium–intracellulare (MAI), histoplasmosis, or other fungal infections

Patients who are severely immunosuppressed may not show well-formed granulomas; instead organisms may be seen in Kupffer cells and within loose aggregates of macrophages (Fig. 44.13 )

Fig. 44.13.

Pneumocystis infection in a patient with HIV showing the typical pink frothy material characteristic of this infection.

♦

AIDS-complicating or AIDS-defining neoplasms such as Kaposi sarcoma or lymphoma may be present in the liver

Special Stains

♦

Ziehl–Neelsen stain d emonstrates acid-fast alcohol-resistant bacilli such as M. tuberculosis and M. avium– intracellulare

♦

Methenamine silver stain demonstrates fungal organisms (Fig. 44.14)

Fig. 44.14.

Methenamine silver stain showing round and semilunar yeast forms of Pneumocystis in a patient with HIV infection.

♦

Trichrome stain demonstrates the degree of fibrosis, especially in patients who are coinfected with hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other viral infections of the liver

Herpes Virus Infections

Epstein–Barr Virus Infection

Clinical

♦

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is an encapsulated double-stranded DNA virus

It is also known as human herpesvirus 4

♦

EBV causes an acute infection called infectious mononucleosis

♦

The incubation period is 5 weeks and 50% of patients are clinically asymptomatic

♦

The liver is involved in 90% of patients who show elevated liver function tests

However, jaundice is seen in only 5% of patients

Microscopic

♦

Microscopic features of infectious mononucleosis include a marked lymphocytic infiltration of the liver by large, atypical-appearing lymphocytes

♦

The inflammatory infiltrate is present in portal tracts as well as the lobules

♦

The latter show a typical sinusoidal pattern of infiltration (sinusoidal lymphocytosis) (Figs. 44.15 and 44.16)

Fig. 44.15.

Involvement of the liver by Epstein–Barr virus showing sinusoidal lymphocytosis without hepatocyte damage, necrosis, or fibrosis.

Fig. 44.16.

Involvement of the liver by Epstein–Barr virus showing large atypical lymphocytes in hepatic sinusoids.

Special Studies

♦

The monospot test is sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis infection

♦

The virus can be demonstrated in liver biopsy specimens by in situ hybridization, which demonstrates a positive reaction in the lymphoid infiltrate

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and hepatitis C may cause a similar pattern of sinusoidal lymphocytosis

♦

Drug-induced hepatitis

♦

Low-grade lymphoproliferative diseases, such as lymphocytic leukemia and gamma delta T-cell lymphoma

Cytomegalovirus Infection

Clinical

♦

CMV infection is clinically mild and self-limiting in most cases

Significant liver disease including acute liver failure occurs due to reactivation of latent infection in patients who are immunosuppressed

♦

This is usually associated with multiorgan damage

♦

CMV infection may be congenital or acquired by blood transfusions

Microscopic

♦

Neonatal infection is typified by giant cell hepatitis with portal and lobular inflammation, giant cell transformation of hepatocytes, and severe cholestasis

♦

CMV infection may mimic the histological features of infectious mononucleosis with sinusoidal lymphocytosis

♦

CMV infection may show randomly distributed punched-out areas of necrosis, which usually contain typical CMV inclusions

♦

Infection occurring in the liver allograft following transplantation may present as small microabscesses scattered in the liver parenchyma

These microabscesses usually surround infected cells and typical CMV inclusions may be seen in their center

♦

Typical CMV inclusions consist of large intranuclear amphophilic bodies with a surrounding halo, often referred to as “owl eye” inclusions

CMV inclusions are usually present in endothelial cells but may also be seen within hepatocytes and bile duct epithelium

Special Studies

♦

The diagnosis can be confirmed by CMV-specific serum antibodies

♦

A sensitive and specific immunohistochemical stain is available, which highlights the CMV antigen in nuclei

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other forms of acute viral hepatitis

♦

Drug-induced hepatitis

♦

EBV infection if there is a pattern of sinusoidal lymphocytosis

Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

Clinical

♦

Liver infection by the herpes simplex virus affects patients who have been immunocompromised due to solid organ transplantation and various immunodeficiency states or who have HIV infection

♦

Both type 1 and type 2 herpes simplex viruses may infect the liver

♦

Patients present with acute hepatitis or acute liver failure

There is marked elevation of LFTs, and disseminated intravascular coagulation is common

Herpes liver infections are associated with a high rate of mortality

Microscopic

♦

Herpes simplex virus typically causes punched-out areas of necrosis within the hepatic parenchyma

These areas are random in distribution and may appear intensely hemorrhagic on both gross and microscopic examinations (Fig. 44.17 )

Fig. 44.17.

Herpes simplex hepatitis showing areas of hemorrhagic necrosis .

♦

Viral inclusions are present at the edge of these areas at their interface with viable liver parenchyma

Typical inclusions are intranuclear and amphophilic with a ground glass appearance (Fig. 44.18 )

Fig. 44.18.

Herpes simplex hepatitis showing amphophilic ground glass intranuclear inclusions of herpes simplex virus.

♦

Cells containing these inclusions often show multinucleation

Special Studies

♦

Sensitive and specific immunohistochemical stains are available for the diagnosis of herpes simplex 1 and herpes simplex 2 viruses

♦

PCR amplification and genome sequencing help to distinguish between type 1 and 2 herpes simplex virus infections

Differential Diagnosis

♦

CMV infection

♦

Toxoplasmosis

Herpes Virus 6 Infection

♦

Herpes virus 6 is a T-cell lymphotropic virus with affinity for CD4 lymphocytes

♦

Primary infection usually occurs in infants, leading to transient cutaneous rash with fever

Herpes virus 6 may rarely cause acute hepatitis and fulminant hepatitis

Herpes Zoster Infection

♦

Herpes zoster almost never affects immunocompetent hosts

Fulminant hepatitis has been reported in immunocompromised patients

Adenovirus Infection

Clinical

♦

Adenovirus is a nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus that causes respiratory tract infection in children

♦

Adenovirus rarely causes hepatitis in immunocompetent individuals. However, severe hepatitis may occur in immunocompromised hosts, progressing rapidly to hepatic failure if not managed urgently

Microscopic

♦

Punched-out areas of necrosis are randomly scattered in the hepatic parenchyma

♦

Viral inclusions are present in hepatocytes at the periphery of these necrotic areas which appear as smudgy nuclei with basophilic “ground glass” appearance

Cytoplasmic aggregates of basophilic viral products may also be present

♦

Areas of necrosis may be accompanied by lymphohistiocytic infiltrates

Special Studies

♦

Immunohistochemistry with specific antibodies aids in the detection of virus

♦

Because a majority of individuals are seropositive for the virus, demonstration of a rising titer over 2–4 weeks is necessary to establish the diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Herpes virus infection

♦

CMV

♦

Toxoplasmosis

Nonviral Infections

Bacterial Infections

Pyogenic Bacterial Infection

Clinical

♦

A wide variety of bacterial organisms may gain access to the liver through the arterial or venous vascular supply or from the biliary tree

♦

Clinical manifestations may be nonspecific such as malaise and fever or specific to the liver such as hepatomegaly and right upper quadrant pain

♦

Prognosis is related to the underlying condition giving rise to the bacterial infection

Microscopic

♦

The findings may be nonspecific in patients who have liver disease due to underlying sepsis

♦

There may be portal edema, ductular reaction, and inflammatory infiltrate

♦

The lobules show varying degrees of canalicular cholestasis and sinusoidal infiltration by neutrophils

♦

Microabscesses may be present which may coalesce to give larger macroscopic abscesses

Special Stains

♦

Gram stain demonstrates bacteria and bacterial colonies

♦

PAS stain demonstrates Entamoeba histolytica, a diagnostic consideration for large abscesses

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Amebic abscess

♦

Extrahepatic biliary obstruction

Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis

Clinical

♦

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, a disease seen in Far Eastern countries , is associated with Clonorchis sinensis infection in about 50% of cases

♦

The main clinical manifestations consist of recurrent symptoms of acute cholangitis

Complications include pancreatitis, liver abscesses, septicemia, cholangiocarcinoma, and portal vein thrombosis

The prognosis is related to complications associated with the recurrent cholangitis

Microscopic

♦

Dilated intrahepatic ducts surrounded by an acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate are seen

There may be biliary epithelial damage (Fig. 44.19 )

Fig. 44.19.

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis showing periductal inflammation, fibrosis, and epithelial damage .

Scarring of the bile ducts might lead to features that resemble sclerosing cholangitis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Extrahepatic obstruction from other causes

♦

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

♦

Caroli disease

Bacillary Angiomatosis

Clinical

♦

Bacillary angiomatosis is a vascular proliferative lesion caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana

♦

Bacillary angiomatosis occurs primarily in immunocompromised patients, such as those with advanced HIV infection

Microscopic

♦

The lesion consists of proliferation of capillaries lined by plump epithelioid-appearing endothelial cells along with a heavy inflammatory cell infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils

♦

The lesion contains numerous organisms that appear as clumps of amphophilic granular material

Special Studies

♦

The bacilli can be demonstrated by the Warthin–Starry stain and immunohistochemistry

♦

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used to identify the causative organisms

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Peliosis hepatis

Brucellosis

Clinical

♦

Brucellosis is caused by the Gram-negative bacilli of Brucella species (B. melitensis, B. abortus, B. suis)

♦

The bacillus is transmitted to humans through ingestion of infected milk products, direct contact with an infected animal, or inhalation of aerosols

Zookeepers or veterinarians occupationally exposed to placental tissues or vaginal secretions of infected animals are most at risk

Human-to-human transmission is not known to occur except in very rare cases

♦

The liver is involved in about 10–15% of cases by hematogenous transmission of the bacilli

♦

The disease is characterized by intermittent fever, which explains its alternative name, “undulant fever”

Brucellosis is also known as Malta fever and Mediterranean fever

♦

The fever is accompanied by headaches, chills, profound weakness, myalgia, and depression

Microscopic

♦

The liver may show a picture of nonspecific reactive hepatitis with prominence of Kupffer cells, a mild inflammatory infiltrate in portal tracts, and portal lobular inflammation

♦

Varying numbers of microgranuloma s consisting of small, tight clusters of epithelioid cells are found scattered in the lobules

Rarely, microabscesses may be present

Special Studies

♦

The diagnosis is made by culturing the organism from the blood or bone marrow

♦

Specific antibodies against Brucella can be detected in serum

Demonstration of a rising titer over 2 weeks is necessary to establish the diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Typhoid fever

♦

Tularemia

♦

Other granulomatous inflammations

Salmonellosis

Clinical

♦

Salmonellosis is caused by the Gram-negative bacilli, Salmonella typhi or Salmonella paratyphi, which are acquired by ingesting infected animal products and, less commonly, infected vegetables

♦

Clinical manifestations of suspected salmonellosis include high fever and relative bradycardia

The liver is almost always involved, but clinical hepatitis is present in 25% of cases

The bacillus can infect the biliary tract

♦

The gallbladder serves as a reservoir for a chronic carrier state which occurs in about 3% of individuals

♦

Diagnosis is made by culturing the bacilli from stool or blood

Microscopic

♦

The main microscopic feature is marked hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the Kupffer cells

♦

Typhoid nodules, which are aggregates of macrophages with focal necrosis, may be randomly scattered in the parenchyma

Mild portal inflammation may be present

Special Studies

♦

The diagnosis is established by culture the bacillus from stools, urine, or blood

♦

Gram-negative organisms may be demonstrated in Kupffer cells

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Brucellosis

Syphilis

Clinical

♦

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum

♦

The liver may be involved in all three stages of the disease

♦

Congenital syphilis is acquired by transmission from mother to fetus

The liver disease may manifest years after birth

Microscopic

♦

Congenital syphilis is characterized by extensive perisinusoidal fibrosis without accompanying inflammation, necrosis, or regeneration (Fig. 44.21)

Fig. 44.21.

Congenital syphilis showing marked sinusoidal fibrosis in the absence of inflammation, necrosis, and fibrosis.

♦

Secondary syphilis shows scattered nonnecrotizing epithelioid granulomas and small vessel vasculitis

♦

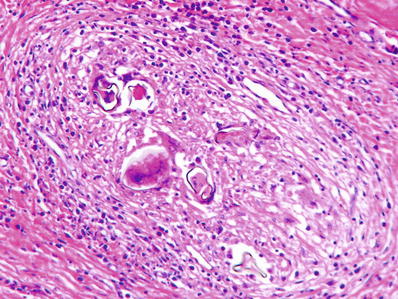

Tertiary syphilis shows gumma (necrotizing granuloma) formation and obliterative endarteritis with dense scar formation (Fig. 44.22 )

Fig. 44.22.

Tertiary syphilis showing gumma with central necrosis surrounded by fibrosis

The extensive scarring gives rise to a nodular liver, which has been referred to as hepar lobatum

♦

Amyloid deposition may also be seen

Special Studies

♦

The spirochetes can be demonstrated by dark-field microscopy, usually in primary chancres

♦

The spirochetes can also be demonstrated in the liver by silver stains

The organism is present in necrotizing lesions as well as in congenital syphilis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Neonatal giant cell hepatitis

♦

Brucellosis/salmonellosis

♦

Drug-induced granulomatous hepatitis

Mycobacterial Infections

Tuberculosis

Clinical

♦

Tuberculosis is caused by the acid-fast alcohol-resistant bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis

♦

The liver is usually involved as part of a systemic infection, in approximately 25% of cases of chronic tuberculosis and 95% of cases of miliary tuberculosis

♦

The liver disease is usually clinically silent

Severe hepatic dysfunction is rare, being overshadowed by the systemic involvement

Liver disease is never the cause of mortality

♦

Elevated liver function tests may be seen

♦

A high degree of suspicion is necessary to diagnose tuberculosis on a liver biopsy because the granulomas are usually nonnecrotizing and the yield of organisms on an acid-fast stain or on culture is relatively low

Microscopic

♦

The microscopic features of tuberculosis include well-defined portal and parenchymal epithelioid granulomas

♦

The granulomas may be necrotizing or nonnecrotizing

Necrotizing granulomas are relatively rare and seen only in very active disease

Special Studies

♦

The bacilli can be demonstrated by a Ziehl–Neelsen stain, but the yield is relatively low

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Sarcoidosis

♦

Other granulomatous liver diseases

Mycobacterium Avium–Intracellulare Infection

Clinical

♦

Infection with M. avium–intracellulare usually occurs in immunocompromised patients such as those with AIDS

Infection of the liver occurs as part of a disseminated infection

♦

The clinical manifestations are systemic and not usually related to the liver

Microscopic

♦

Nonnecrotizing ill-defined granulomas are present in portal tracts and lobules

♦

Severely immunocompromised patients may not be able to mount a granulomatous response, and the bacilli are present in Kupffer cells and clusters of foamy macrophages

The lesions are nonzonal in distribution

Special Studies

♦

The PAS and Ziehl–Neelsen stains demonstrate abundant bacilli within macrophages and Kupffer cells

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Tuberculosis

♦

Fungal infectio ns

Leprosy

Clinical

♦

Leprosy is caused by M. leprae and affects an estimated 20 million people worldwide, especially in tropical climates

♦

Hepatic granulomas are present in more than 50% of patients who are infected

Hepatic involvement does not lead to clinical manifestations

♦

Systemic amyloidosis is a frequent complication

♦

The disease is difficult to eradicate and most of the morbidity occurs from consequences of nerve destruction

Microscopic

♦

The microscopic picture resembles the entire spectrum of lesions seen in the skin disease

♦

The tuberculoid type of leprosy shows well-formed granulomas, whereas the lepromatous type shows ill-formed granulomas and clusters of foamy histiocytes

♦

During a lepromatous reaction, necrosis is seen within the liver lesions

Special Studies

♦

Fite stain demonstrates the acid-fast bacilli

♦

Silver stains may demonstrate nonviable organisms

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Sarcoidosis

♦

Tuberculosis

Rickettsial Infection

Clinical

♦

Q fever is caused by Coxiella burnetii and Rocky Mountain spotted fever by Rickettsia rickettsii

These organisms have numerous nonhuman reservoirs, which include arthropods, birds, and mammals

♦

Clinical manifestations include high fevers, chills, sweating, and myalgia

Most patients present with pneumonia manifested by shortness of breath, cough, and sputum production

♦

The liver is involved in 85% of cases, but most patients do not demonstrate liver disease

Liver involvement is indicated by hepatomegaly and abnormal liver tests

Microscopic

♦

The distinctive lesion of Q fever is the fibrin ring granuloma, which consists of a central fat vacuole surrounded by a complete or partial fibrin ring with an outer cuff of epithelioid cells and macrophages (Fig. 44.23)

Fig. 44.23.

Rickettsial hepatitis showing a fat vacuole surrounded by a fibrin ring – the “fibrin ring granuloma.”

♦

This lesion is, however, not always present and, in many instances, only portal inflammation and prominent Kupffer cell hyperplasia may be seen

♦

The fibrin ring granuloma is not specific for Q fever and has been described in hepatitis C viral infection, lymphomas, and drug toxicity

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other granulomatous diseases

♦

Fibrin ring granulomas have been described in hepatitis C viral infection, lymphomas, and drug toxici ty

Fungal Infections

Histoplasmosis

Clinical

♦

Histoplasmosis is caused commonly by Histoplasma capsulatum and less commonly by H. duboisii

♦

The organism is highly endemic in the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys and in South America

It is carried by birds and is acquired by humans through inhalation

♦

The infection is asymptomatic in 90% of cases and does not cause significant pathology in immunocompetent individuals

In immunocompromised patients such as those receiving corticosteroids or patients with AIDS, infection of the liver occurs as part of a disseminated systemic disease

♦

Mortality is high in untreated asymptomatic patients who have disseminated disease

Microscopic

♦

In most individuals living in endemic areas, the lesion consists of scarred and calcified granulomas, which are discovered incidentally on the surface of the liver during surgery

These are often sampled for frozen section to rule out metastatic disease

♦

In others, epithelioid granulomas may be seen, some of which may be necrotizing

♦

In patients who are severely immunocompromised, abundant organisms may be found without well-formed granulomas, usually within Kupffer cells or loose collections of macrophages

Special Studies

♦

The organism can be easily demonstrated by the PAS and silver stains

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other granulomatous infections

Coccidioidomycoses

Clinical

♦

Coccidioidomycoses is caused by Coccidioides immitis, which is endemic in southwestern USA and South America

♦

The infection is usually a benign, self-limited pulmonary disease

♦

Disseminated disease with liver involvement may occur in immunocompromised individuals

♦

The mortality is high in untreated symptomatic disease

Microscopic

♦

The main lesion of coccidioidomycoses consists of epithelioid granulomas with multinucleated giant cells containing the organism

The organisms vary in size, from 20 to 200 nm spherules

♦

No calcifications are seen

♦

There may be an accompanying mild inflammatory infiltrate in portal tracts

Special Studies

♦

PAS and silver stains demonstrate the organisms

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other granulomatous infections

Parasitic Infections

Amebic Abscess

Clinical

♦

Amebic abscess of the liver is caused by Entamoeba histolytica, which enters the liver from the intestine through the portal vein

♦

The clinical manifestations are usually protean in the early stages and include fever and right upper quadrant pain

♦

As the abscess enlarges, there might be leukocytosis, pain, and hepatomegaly

Most patients do not remember preceding bowel symptoms

♦

Most patients have positive serologies, even in the early stages of the disease

Macroscopic

♦

There is usually a single abscess, most often in the right lobe, which can vary from a few centimeters to up to 20 cm in diameter

♦

The abscess consists of a central necrotic area containing a reddish-brown fluid, which is often described as having an anchovy sauce appearance

♦

The periphery of the abscess shows shaggy necrotic walls

♦

Older abscesses may develop fibrous capsules

Microscopic

♦

The amoebae are usually present at the advancing edge of the abscess but might also be present within necrotic fluid when it is aspirated

♦

The amoebae are round unicellular organisms 20–50 μm in diameter

They have a round, central to eccentric nucleus and clear to purple granular cytoplasm

The nucleus has a sharp nuclear membrane and a prominent central karyosome

Numerous phagocytosed erythrocytes are present within the cytoplasm and are pathognomic of amebic trophozoites

Special Studies

♦

An immunohistochemical stain is available for the diagnosis of E. histolytica

♦

A PAS stain shows intense cytoplasmic staining due to the accumulation of glycogen in the cytoplasm

♦

On an H&E stain, phagocytosed erythrocytes are diagnostic of ameba

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Pyogenic abscess

♦

Necrotic tumor mass

Malaria

Clinical

♦

Liver involvement in malaria is usually caused by Plasmodium falciparum of which 100 million cases are reported worldwide per year

♦

The malarial parasite requires multiplication within the liver after infection

The schizonts develop within hepatocytes and then infect erythrocytes

♦

Liver damage occurs due to ischemic necrosis caused by the adherence of the parasite to liver venules and engorgement of sinusoids by infected erythrocytes

♦

Malaria may be associated with a hypoglycemic state

This is usually seen in African children and adult pregnant women

In these cases, there is complete absence of glycogen in hepatocytes

♦

Individuals at increased risk of mortality from P. falciparum include children, pregnant women, and those who are immunocompromised

Microscopic

♦

Hemozoin is present extensively in Kupffer cells and in portal macrophages (Fig. 44.26)

Fig. 44.26.

Hemozoin deposition in Kupffer cells in malaria. Hemozoin appears as a dark brown pigment on H&E stain.

Hemozoin is an iron–porphyrin–protein complex, which is formed by the breakdown of hemoglobin

♦

Scattered areas of necrosis are seen

♦

Sinusoidal congestion with parasite-filled Kupffer cells and red blood cells is present

♦

In patients with the hyperreactive malarial splenomegaly syndrome (tropical splenomegaly syndrome), the liver may show sinusoidal lymphocytosis

Special Studies

♦

The hemozoin pigment is negative with Prussian blue reaction

♦

Immunohistochemical stain for Plasmodium species is available

Differential Diagnosis

♦

The accumulated pigment can be differentiated from hemosiderin by the Prussian blue reaction

♦

A similar pigment can also be seen in schistosomiasis

Hydatid Cyst

Clinical

♦

Hydatid cyst is caused by Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis , which are transmitted to humans by ingestion of foods contaminated by eggs of the parasite

The oncospheres translocate to the liver via the portal vein

♦

The cyst is usually asymptomatic when small

As it enlarges, the cyst may cause hepatomegaly and pain in the upper right quadrant

♦

Complications include biliary obstruction, cholangitis, and bacterial superinfection

Rarely the cyst may rupture into the liver or into the peritoneal cavity and cause dissemination of the disease

♦

Treatmen t consists of PAIR – puncture, aspiration, injection, and reaspiration

The cyst is aspirated and injected with hypertonic saline to kill the scolices

The cyst is reaspirated after 15 min

Macroscopic

♦

E. granulosus causes unilocular cysts, while E. multilocularis causes multilocular cysts

♦

Cysts may attain large sizes, up to 25 cm in diameter

♦

Calcifications in the wall of the cyst are common

Microscopic

♦

The cyst consists of two layers:

The outermost layer is an acellular laminated membrane about 1 mm thick, which is ivory white, friable, and slightly slippery

The inner layer consists of a germinal membrane, which is transparent and consists of nucleated cells

♦

Attached to the germinal membrane and budding from it are ovoid protoscolices, which contain hooklets and a sucker

♦

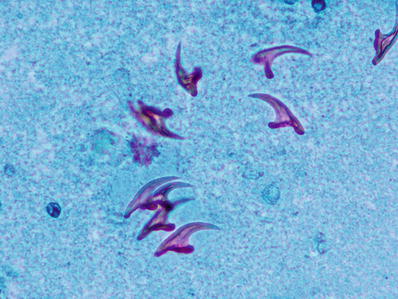

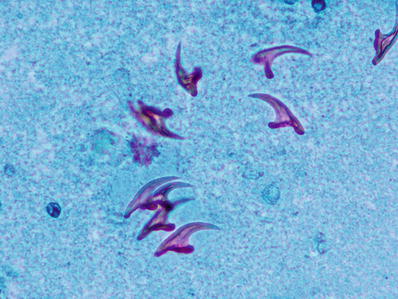

Scolices and hooklets in fluid aspirated from the cyst are diagnostic (Fig. 44.27 )

Fig. 44.27.

Hooklets from the sediment of a hepati c hydatid cyst.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Amebic abscess

Clonorchiasis ( Infection by Liver Flukes)

Clinical

♦

Infection by the liver flukes Clonorchis and Opisthorchis occurs in the Far East

C. sinensis is prevalent in China, Hong Kong, Korea, Vietnam, and Taiwan

O. viverrini is frequent in northeast Thailand

♦

Human infection is acquired by ingesting cercariae in uncooked freshwater fish

♦

Immature worms settle in the biliary tract and, occasionally, within the pancreatic duct

The worms live in the biliary tree for 10 and, sometimes, up to 25 years

The worms release eggs in the biliary tree which may be detected in feces

♦

Most infections are asymptomatic

Eosinophilia is present in most patients, even those who are asymptomatic

♦

Symptoms result from obstruction of the bile duct and infections secondary to obstruction

Severe infections cause recurrent pyogenic cholangitis with repeated bouts of cholangitis

♦

Abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, and jaundice may also be present

♦

A long-term complication of clonorchiasis is cholangiocarcinoma

Macroscopic

♦

The liver is enlarged with gray and pale blue subcapsular cysts, which represent dilated ducts

The dilated ducts contain parasites and are surrounded by fibrosis

♦

Intrahepatic and extrahepatic calculi may be present

Microscopic

♦

Large intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts are dilated and contain parasites (Fig. 44.28 )

Fig. 44.28.

Clonorchis sinensis in a large bile duct, which shows proliferation of small peribiliary glands.

The parasites range from 8 to 25 mm in length and are 2–5 mm wide

♦

There is periductal inflammation and fibrosis

♦

Proliferation of periductal glands is common

♦

The upstream, smaller bile ducts may show signs of obstruction with a ductular reaction

♦

Cholangitis may be present

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Mechanical duct obstruction

Schistosomiasis

Clinical

♦

Schistosomiasis is a worldwide disease, caused by Schistosoma mansoni, S. japonicum, and S. mekongi

♦

Human infection is acquired when schistosomal cercariae infiltrate the skin from infected waters

Following development, the adult worms settle in the mesenteric and portal veins, and 4 weeks later, the females commence laying eggs

While many eggs are excreted into feces, a significant number pass into the portal veins

♦

Most infections are asymptomatic ; clinically evident disease is present in approximately 10% of people

The manifestations result from portal hypertension and its consequences

During acute infection, some patients may have what is called “Katayama fever,” a syndrome characterized by fever, systemic upset, eosinophilia, and transient hepatomegaly

Microscopic

♦

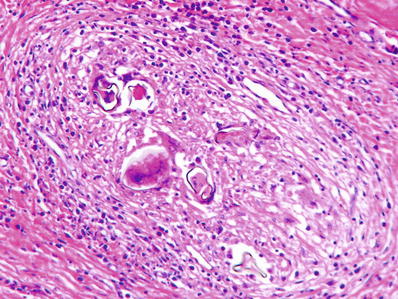

The eggs are first trapped in the portal venules, giving rise to an acute reaction of eosinophils (Figs. 44.29 and 44.30)

Fig. 44.29.

Schistosomiasis showing several eggs surrounded by an intense granulomatous inflammation .

Fig. 44.30.

Schistosomiasis showing intense eosinophilic inflammation . Deeper sections showed a Schistosoma egg within this infiltrate.

The inflammation is followed by fibrosis

♦

Extensive fibrosis of the portal veins and portal tracts leads to a characteristic “pipe-stem” fibrosis, which is the pathologic basis of portal hypertension seen clinically

♦

Eggs can be identified in early lesions before they undergo degeneration

The eggs of S. mansoni bear a lateral spine, whereas those of S. japonicum have a small lateral spine

Special Studies

♦

The eggs of Schistosoma stain with acid-fast stain; however, this is rarely required for diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Infestation by other parasites and nematodes

Other Hepatitides

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Clinical

♦

Autoimmune hepatitis occurs in young to middle-aged females who usually present with jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly

♦

About one-half of all patients have other autoimmune diseases

Some patients may have concomitant primary biliary cirrhosis or primary sclerosing cholangitis (overlap syndrome)

♦

Serum IgG is elevated

♦

Autoantibodie s are present in serum, including antinuclear antibody (ANA), smooth muscle antibody (SMA), anti-liver kidney microsomal (LKM), anti-liver membrane antibody (LMA), and anti-liver-specific lipoprotein (LSP)

These autoantibodies are sensitive, but not specific, markers of autoimmune hepatitis

Antimitochondrial antibodies (AMAs) are not seen in high titers unless there is overlap with primary biliary cirrhosis

♦

Corticosteroids form the mainstay of therapy

♦

Prognosis is good in patients who respond to immunosuppressive therapy

Microscopic

♦

The most prominent feature is portal inflammation with numerous plasma cells

Plasma cells are not present in all cases of autoimmune hepatitis

Lymphocytes, including lymphoid aggregates, may be the only cell type in a significant number of cases

♦

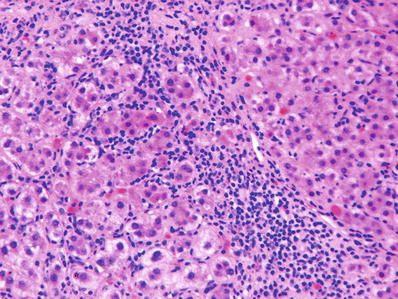

Severe interface hepatitis by a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is the hallmark of untreated autoimmune disease (Figs. 44.31, 44.32, and 44.33)

Fig. 44.31.

Autoimmune hepatitis showing severe interface activity.

Fig. 44.32.

Autoimmune hepatitis showing lymphoid aggregates in portal tracts .

Fig. 44.33.

Autoimmune hepatitis showing an inflammatory infiltrate rich in plasma cells.

♦

Lobular inflammation accompanies the periportal inflammation

It is variable in severity, and in some patients, there may be confluent areas of necrosis (collapse)

♦

Inflammation recedes with successful immunosuppression and biopsies in such patients may show minimal inflammation, if any at all

♦

Varying degrees of portal fibrosis may be seen

Some patients may have significant fibrosis at presentation

Disease that is inadequately treated or that is partially responsive may ultimately lead to cirrhosis

Special Studies

♦

Serum autoantibody assays

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Viral hepatitis

♦

Drug-induced hepatitis

Neonatal Giant Cell Hepatitis

Clinical

♦

Neonatal giant cell hepatitis refers to an injury pattern seen in neonates with a wide variety of liver diseases

The most frequently associated disorder is alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

Numerous other metabolic, infectious, and inherited diseases produce a similar clinical and microscopic picture

♦

Patients present with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and signs and symptoms which reflect the underlying disease

The biliary tree is usually normal on imaging

♦

The overall prognosis depends on the underlying etiology

Microscopic

♦

The microscopic pattern is one of cholestasis with associated hepatocellular damage

♦

The hallmark is syncytial giant cell transformation of hepatocytes , which are present in a diffuse distribution

They are accompanied by lobular disarray and portal and lobular inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 44.34)

Fig. 44.34.

Neonatal hepatitis showing multinucleated syncytial giant hepatocytes.

The giant cells are thought to reflect hepatocyte cell fusion and/or mitotic inhibition

♦

Varying degrees of canalicular and cellular cholestasis are found

There may be mild bile ductular reaction

Although a few multinucleated giant cells may be present, extrahepatic biliary atresia does not produce the classical findings of giant cell hepatitis

♦

The portal tract changes in biliary atresia overshadow those in the lobules

♦

Varying degrees of extramedullary hematopoiesis are usually present

♦

Viral inclusions when present provide a clue to the etiology

Special Studies

♦

Immunohistochemical stains and/or PAS–diastase to rule out alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Extrahepatic biliary atresia

♦

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

Granulomatous Hepatitis

General Features

♦

Granulomas are present in approximately 10% of all liver biopsy specimens

♦

They are associated with a variety of causes including infections, drugs/medications, primary biliary cirrhosis, and sarcoidosis

Tuberculosis and sarcoidosis are the most common causes of liver granulomas worldwide

Other associated conditions include fungal infections, schistosomiasis, hypersensitivity reactions to drugs, foreign body material in IV drug users, and primary biliary cirrhosis

Approximately 10% of granulomas remain idiopathic after all investigations

♦

Microscopically, the granulomas are composed of a collection of epithelioid macrophages with variable number of multinucleated giant cells

They may be well defined or poorly formed

They may be necrotizing or nonnecrotizing

Other inflammatory cells may be present in variable numbers

♦

Lipogranulomas contain lipid vacuoles surrounded by epithelioid cells admixed with other inflammatory cells

♦

Fibrin ring granulomas consist of a central lipid vacuole surrounded by a fibrin ring and inflammatory cells

Sarcoidosis

Clinical

♦

Liver granulomas occur in 60–90% of all cases of systemic sarcoidosis ; however, most patients do not show clinical manifestations of liver disease

Asymptomatic elevations in liver tests occur in a significant number of patients

♦

Primary presentation with liver disease is rare but well known

These patients usually have asymptomatic pulmonary and lymph node involvement

♦

Symptomatic liver disease may present as a cholestatic syndrome resembling primary biliary cirrhosis or primary sclerosing cholangitis or with signs and symptoms of portal hypertension

Rare presentations include the Budd–Chiari syndrome and extrahepatic biliary obstruction due to compression of the hepatic veins or bile ducts by enlarged lymph nodes

♦

Prognosis is usually determined by the pulmonary disease

Microscopic

♦

Nonnecrotizing epithelioid granulomas, which often coalesce, are seen

♦

The granulomas are usually located in the portal and periportal regions but may also be lobular (Fig. 44.35)