Headaches are common in young folks but not in the elderly. A new headache in mid to old age should always be taken seriously. In the elderly a new headache should raise the suspicion of temporal (also known as cranial) arteritis, and prompt evaluation with a sedimentation rate (ESR), which is typically very high.

Temporal (Cranial) Arteritis

Temporal arteritis is a granulomatous giant cell arteritis (GCA) involving the extracranial branches of the aorta that is associated with headache, fever, and a very high sedimentation rate.

Temporal arteritis is a granulomatous giant cell arteritis (GCA) involving the extracranial branches of the aorta that is associated with headache, fever, and a very high sedimentation rate.

Jaw claudication during mastication (masseter muscle ischemia) is a specific symptom that is very useful diagnostically.

Jaw claudication during mastication (masseter muscle ischemia) is a specific symptom that is very useful diagnostically.

The feared complication of temporal arteritis is blindness from involvement of the ophthalmic circulation.

The feared complication of temporal arteritis is blindness from involvement of the ophthalmic circulation.

Visual symptoms with headache should be considered a medical emergency. Temporal artery biopsy frequently (but not always) secures the diagnosis of GCA. High-dose steroid (60-mg prednisone per day) is effective treatment. The dose is tapered down following symptoms and ESR. Remission usually occurs after 1 or 2 years.

Migraine

Migraine is a vascular headache (vasoconstriction, followed by vasodilation) that usually begins at an early age. The pain results from the stretching of receptors in the adventitia of extra- and intracranial vasculature. Migraine is unilateral (favoring predominantly one side) and throbbing.

Migraine is a vascular headache (vasoconstriction, followed by vasodilation) that usually begins at an early age. The pain results from the stretching of receptors in the adventitia of extra- and intracranial vasculature. Migraine is unilateral (favoring predominantly one side) and throbbing.

Nausea and vomiting are frequent; visual aura may be present (scintillating scotomata).

Migraine is worsened by alcohol ingestion, pregnancy, and oral contraceptive use. Some foods may trigger attacks.

Migraine is worsened by alcohol ingestion, pregnancy, and oral contraceptive use. Some foods may trigger attacks.

Untreated, prolonged attacks may not be relieved until awakening after sleep. Neurologic signs and symptoms may occur (hemiplegic migraine), with or without the headache, reflecting the vasoconstriction.

Migraine frequently occurs after a stressful period is resolved (the Friday afternoon headache) in distinction to tension headache which occurs during the stress.

Migraine frequently occurs after a stressful period is resolved (the Friday afternoon headache) in distinction to tension headache which occurs during the stress.

Migraine may be more common in left-handed people although this is controversial. It may also be associated with an autoimmune diathesis. Migraineous attacks may be preceded by a period of hypomania.

Tension Headache

Tension headaches are associated with muscle spasm in the neck and scalp.

Tension headaches are associated with muscle spasm in the neck and scalp.

The pain is felt as a constricting band in association with neck stiffness. In contrast to migraine alcohol ingestion tends to relieve the pain. Tension headaches may trigger migraines and vice versa.

Headaches with Increased Intracranial Pressure

Headaches caused by brain tumors (increased intracranial pressure [ICP]) usually do not interfere with sleep but are typically present on awakening.

Headaches caused by brain tumors (increased intracranial pressure [ICP]) usually do not interfere with sleep but are typically present on awakening.

Any headache present on awakening should raise suspicion of increased ICP.

The so-called hypertensive headaches are occipital in location and also present on awakening. These may reflect nocturnal increases in ICP and usually signify severe or malignant hypertension.

The so-called hypertensive headaches are occipital in location and also present on awakening. These may reflect nocturnal increases in ICP and usually signify severe or malignant hypertension.

Most headaches noted in hypertensive patients reflect the unrelated simultaneous occurrence of two common diseases.

Most headaches noted in hypertensive patients reflect the unrelated simultaneous occurrence of two common diseases.

The presence of venous pulsations in the eye grounds categorically rules out increased ICP; the absence of these is not evidence of increased pressure unless it was known for certain that these had been present previously.

The presence of venous pulsations in the eye grounds categorically rules out increased ICP; the absence of these is not evidence of increased pressure unless it was known for certain that these had been present previously.

Venous pulsations are yet another demonstration of the importance of establishing a baseline of physical findings.

Headache secondary to sinus congestion has a peculiar predilection for the mid to late afternoon for reasons that remain obscure.

Headache secondary to sinus congestion has a peculiar predilection for the mid to late afternoon for reasons that remain obscure.

Nasal decongestants relieve this type of headache.

Headache is the predominant symptom of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri).

Headache is the predominant symptom of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri).

This disorder of young women, frequently associated with obesity, also causes diplopia, visual symptoms, and if severe threatens sight from pressure on the optic nerves. Imaging reveals slit-like ventricles and frequently an “empty” sella.

The syndrome is caused by defective clearance of CSF and acetazolamide is effective treatment in many cases.

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH)

Although not typically associated with headache, NPH, like pseudotumor cerebri, is a disorder of CSF clearance, presumably at the level of the arachnoid granulations. As a consequence the ventricles enlarge impinging on the cortex and subcortical structures.

The classic triad of NPH is gait disturbance, incontinence, and dementia.

The classic triad of NPH is gait disturbance, incontinence, and dementia.

Diagnosis depends on imaging and the response to CSF drainage.

CT and MRI of the brain in NPH show dilated ventricles, no obstruction at the level of the aqueduct, and no enlargement of the sulci, the latter a distinguishing point between NPH and diffuse cortical atrophy.

CT and MRI of the brain in NPH show dilated ventricles, no obstruction at the level of the aqueduct, and no enlargement of the sulci, the latter a distinguishing point between NPH and diffuse cortical atrophy.

Lumbar puncture with the removal of 30 to 50 mL of CSF often results in immediate, or sometimes delayed, improvement in gait and cognition. A ventricular peritoneal shunt provides long-term improvement in about 60% of patients.

NPH is important to recognize because it is a potentially reversible form of dementia.

NPH is important to recognize because it is a potentially reversible form of dementia.

ACUTE CEREBROVASCULAR EVENTS (STROKES)

Hypertension is the major risk factor for all cerebrovascular events.

Hypertension is the major risk factor for all cerebrovascular events.

The overwhelming majority of strokes (about 85%) are ischemic, the remainder being hemorrhagic. Noncontrast CT scan is the first study required in stroke patients to rule out intracerebral hemorrhage.

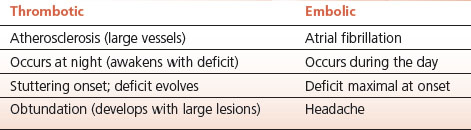

TABLE 14.1 Ischemic Strokes Involving the Cortex

Ischemic Strokes

Ischemic strokes are embolic or thrombotic; the territory served by the middle cerebral artery is most commonly affected.

Ischemic strokes are embolic or thrombotic; the territory served by the middle cerebral artery is most commonly affected.

The clinical features may often distinguish embolic and thrombotic strokes affecting the cerebral cortex (Table 14-1). Thrombotic strokes may be further subdivided into cortical and subcortical (white matter or lacunar infarcts).

Embolic strokes are of sudden onset, occur during the day, are frequently associated with headache, occasionally with a seizure, and the associated neurologic deficit is maximal at onset.

Embolic strokes are of sudden onset, occur during the day, are frequently associated with headache, occasionally with a seizure, and the associated neurologic deficit is maximal at onset.

Emboli most frequently originate in the heart with atrial fibrillation as the major associated abnormality. Vegetations on the heart valves, recent myocardial infarction, or prosthetic heart valves are also important causes.

Paradoxical emboli result from venous thrombosis with embolization of clot through a patent foramen ovale.

Paradoxical emboli result from venous thrombosis with embolization of clot through a patent foramen ovale.

Ultrasonic demonstration of both the venous thrombosis and a patent foramen ovale by cardiac echo with a bubble study establishes the diagnosis.

The sudden onset of Wernicke’s (fluent) aphasia is virtually always embolic.

The sudden onset of Wernicke’s (fluent) aphasia is virtually always embolic.

Speech in Wernicke’s aphasia, although fluent in distinction to the halting speech of Broca’s aphasia, is incomprehensible gibberish (“word salad”).

Thrombotic stroke typically occurs at night during sleep; the patient wakes up with the deficit.

Thrombotic stroke typically occurs at night during sleep; the patient wakes up with the deficit.

The deficit from a thrombotic stroke may evolve over the course of 1 or 2 days. If the affected area is large, edema around the lesion may result in somnolence in the days following the stroke with subsequent improvement in consciousness as the swelling subsides.

Strokes affecting the nondominant hemisphere (right parietal lobe in right-handed people with left-sided cerebral dominance) are associated with striking neglect of the affected side.

Strokes affecting the nondominant hemisphere (right parietal lobe in right-handed people with left-sided cerebral dominance) are associated with striking neglect of the affected side.

This is often obvious from the position of the patient in the bed, who lies turned away from the affected (left) side. Having the patient draw a clock makes a nice demonstration of the neglect – all the numbers are on the right side. Astereognosis and sensory extinction on the affected side may also be demonstrable. Neglect is an important factor that hinders rehabilitation of nondominant hemisphere strokes.

Watershed strokes result from ischemia in the territory at the junction of the anterior and posterior circulations; they typically occur in patients with cardiovascular disease after an episode of hypotension with attendant poor perfusion of these vulnerable areas.

Watershed strokes result from ischemia in the territory at the junction of the anterior and posterior circulations; they typically occur in patients with cardiovascular disease after an episode of hypotension with attendant poor perfusion of these vulnerable areas.

Cardiac surgery is a common cause of watershed lesions. Involvement of the occipital cortex (between the anterior and posterior circulations) may result in cortical blindness. In the latter, pupillary reactions are preserved while vision is seriously impaired. About 50% of patients with cortical blindness are unaware of, or deny, their loss of sight.

Lacunar infarcts result from occlusion of smaller penetrating arteries in the region of the basal ganglia and the internal capsule. Lacunes account for about one-quarter of all ischemic strokes.

Lacunar infarcts result from occlusion of smaller penetrating arteries in the region of the basal ganglia and the internal capsule. Lacunes account for about one-quarter of all ischemic strokes.

The occlusion may reflect structural abnormalities of the small vessels or atheromatous occlusion at the origin of the penetrating vessels from the major branches of the middle cerebral arteries or the circle of Willis. Hypertension is presumed to be the usual underlying cause.

Isolated motor weakness of the upper or lower extremity or the face is the most common deficit produced by lacunes, but pure sensory strokes, ataxia, and dysarthria also occur.

Isolated motor weakness of the upper or lower extremity or the face is the most common deficit produced by lacunes, but pure sensory strokes, ataxia, and dysarthria also occur.

Lacunes may also be silent.

Cerebral Hemorrhage

Three lesions account for the majority of intracranial and intracerebral hemorrhage: “berry” or saccular aneursyms; microaneursyms of Charcot and Bouchard; and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA).

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is associated with severe (“thunderclap”) headache, nuchal rigidity, and, frequently, reduced level of consciousness.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is associated with severe (“thunderclap”) headache, nuchal rigidity, and, frequently, reduced level of consciousness.

Noncontrast CT establishes the diagnosis in the great majority of cases.

Funduscopic examination in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage commonly reveals blurred disc margins and retinal hemorrhages occur in about 25% of cases.

Funduscopic examination in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage commonly reveals blurred disc margins and retinal hemorrhages occur in about 25% of cases.

Rupture of a “berry” aneurysm is the usual cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Polycystic kidney disease and coarctation of the aorta are predisposing diseases.

Rupture of a “berry” aneurysm is the usual cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Polycystic kidney disease and coarctation of the aorta are predisposing diseases.

Resulting from a defect in the muscular wall of the artery, berry aneursyms are most common in first or second order branches of arteries arising from the circle of Willis; the great majority are located in the anterior circulation.

The microaneursyms of Charcot and Bouchard are important causes of intracerebral hemorrhage. These tiny aneurysms originate from very small arteries most commonly in the region of the basal ganglia (lenticulostriate arteries).

The microaneursyms of Charcot and Bouchard are important causes of intracerebral hemorrhage. These tiny aneurysms originate from very small arteries most commonly in the region of the basal ganglia (lenticulostriate arteries).

Antecedent hypertension is the usual cause. These microaneursyms are distinct from the larger berry aneurysms that cause subarachnoid hemorrhage.

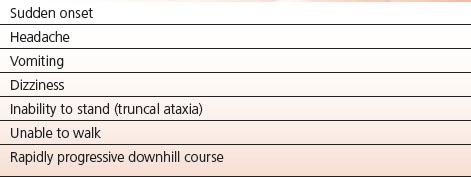

Acute cerebellar hemorrhage is a medical emergency; prompt recognition followed by surgical evacuation of the hematoma is lifesaving (Table 14-2).

Acute cerebellar hemorrhage is a medical emergency; prompt recognition followed by surgical evacuation of the hematoma is lifesaving (Table 14-2).

Like other intracerebral hemorrhages, the cause of cerebellar hemorrhage appears to be rupture of tiny microaneursyms as described by Charcot and Bouchard.

The clinical presentation of acute cerebellar hemorrhage includes the sudden onset of headache, vomiting, dizziness, and, particularly, the inability to stand or walk.

The clinical presentation of acute cerebellar hemorrhage includes the sudden onset of headache, vomiting, dizziness, and, particularly, the inability to stand or walk.

The inability to walk or even stand, with a tendency to fall backward is due to cerebellar ataxia and, along with intractable vomiting is an important clue to the diagnosis. Weakness of lateral gaze may be present as well. The disability usually progresses rapidly, so speed in diagnosis (noncontrast CT) and clot evacuation are critical. This is one instance where correct diagnosis and treatment results in cure without permanent disability but failure to diagnose and treat results in death. A high index of suspicion is necessary.

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is an important cause of intracerebral hemorrhage in the elderly. It is the usual cause in patients who have no history of hypertension.

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is an important cause of intracerebral hemorrhage in the elderly. It is the usual cause in patients who have no history of hypertension.

TABLE 14.2 Acute Cerebellar Hemorrhage

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree