15 Neurology

Diplopia

Case history (1)

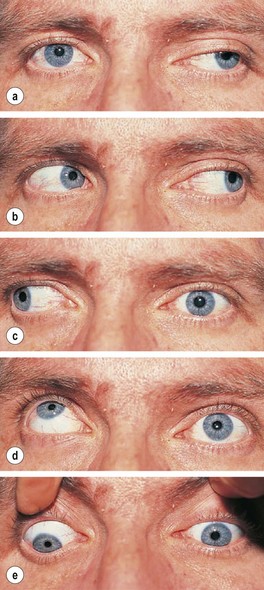

On examination there is ptosis in the left eye and the eye is deviated downwards and laterally (down and out) and fails to elevate or move medially (Fig. 15.1). The pupils both react normally. He is otherwise well. Random blood glucose is 11.5 mmol/L. HbA1c is 8% (64 mmol/mol).

What immediate action would you take?

• Achieve better diabetic control.

• Reassure that recovery is likely (but not definite) over weeks.

If no recovery, refer to a neurologist for MRI scan and investigation of causes of mononeuritis multiplex (see p. 471).

Information

• A painless third nerve palsy with preserved pupil reactions commonly occurs in the setting of diabetes due to nerve infarction.

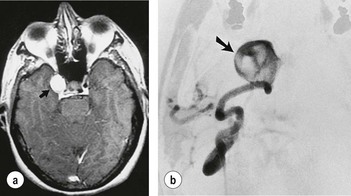

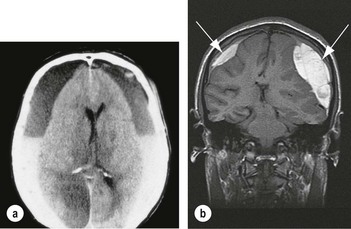

• If there is headache, especially of sudden onset, a posterior communicating artery aneurysm compressing the third nerve in front of the midbrain is a likely cause. Such a lesion also commonly involves the parasympathetic pupillary constricting fibres so that the pupil is fixed and dilated. MR angiography is indicated in this situation (Fig. 15.2).

What action would you take?

Confirm diagnosis of myasthenia by:

• Serum acetylcholine receptor antibodies (present in 40% of cases with eye involvement only with 100% specificity).

• Perform EMG studies, including the extra-ocular muscles.

This patient was diagnosed as having myasthenia gravis and was referred urgently to a neurologist. Myasthenia gravis is sometimes restricted to the ocular system and can present as a variable gaze palsy that is difficult to interpret in terms of individual muscles or cranial nerves. There is not always a history of fatiguability. Some of the many causes of diplopia are listed in Table 15.1.

| Muscle/obstructive | Thyroid eye disease |

| Orbital masses | |

| Orbital pseudotumour (ocular myositis) | |

| Myasthenia | |

| Latent squint (visible when tired) | |

| Cranial nerves | Mass lesion in path of III, IV or VI nerves |

| Mononeuritis multiplex | |

| False localising due to raised intracranial pressure | |

| Central | Brainstem inflammation, demyelination, brainstem mass lesion, infarction, haemorrhage |

What action would you take?

In this case the ventricles were normal and therefore it was safe to proceed to a lumbar puncture. The opening pressure was recorded at 30 cm (normal pressure < 25 cm). A volume of CSF (usually around 20 mL) should be removed, so as to approximately halve the opening pressure.

Loss of vision

What is the differential diagnosis?

Transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) are usually diagnosed clinically. Other causes of visual loss are shown in Table 15.2.

Table 15.2 Causes of acute or transient visual disturbance

| Ophthalmological | Neurological |

|---|---|

| Glaucoma | Optic neuritis/demyelination |

| Amaurosis fugax | Compressive lesion of the optic nerve, chiasm, tract |

| Giant cell (temporal) arteritis | TIA/stroke of posterior cerebral circulation |

| Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy | Migraine |

| Central retinal vessel occlusion | Occipital, temporal, parietal haemorrhage |

| Vitreous haemorrhage | Occipital, temporal, parietal space-occupying lesion |

| Retinal detachment | Temporal lobe epilepsy |

| Uveitis, keratitis | Raised intracranial pressure |

Remember giant cell arteritis, which causes acute visual loss. It responds to steroids (see p. 182).

Treatment

• Paracetamol 1 g, aspirin 900 mg (dispersible formulation) or an NSAID, e.g. ibuprofen 400–600 mg or naproxen 500 mg is given, as early as possible during an attack. Gastric emptying is reduced during the attack so dispersible formulations are preferred.

• Antiemetics (e.g. metoclopramide 10 mg or domperidone 10 mg).

• If these measures are ineffective, use a 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT)1B/1D serotonin receptor agonist (triptan). These drugs relieve both the pain and the nausea. Triptans should be avoided in patients with vascular disease or uncontrolled/severe hypertension. Triptans should be given at the onset of the headache (e.g. during the aura phase). There are several triptans available with a spectrum of efficacy, e.g.:

• If there is no response to an initial dose, do not persist with subsequent doses during the same attack. However, the drug may be effective in subsequent attacks.

Bell’s palsy

An acute VII nerve lesion, Bell’s palsy (Fig. 15.4) is usually due to a viral infection (often herpes simplex). It involves the VII facial nerve (motor only) with occasionally a loss of taste on the tongue and hyperacusis. There should be no sensory loss or other cranial nerve involvement.

Note:

• Sarcoidosis should be suspected in cases of bilateral Bell’s palsy.

• A rare condition causing bilateral Bell’s palsy and tongue swelling with other features is Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome.

• Progressive multiple cranial nerve palsies should lead to suspicion of malignant meningitis, or lymphomatous or carcinomatous infiltration.

Vertigo

What is the likely diagnosis?

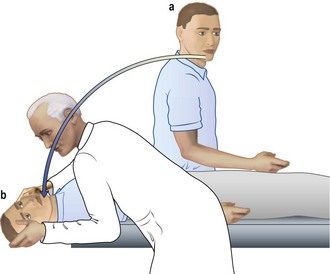

Peripheral vestibular lesions are characterised by positional vertigo, i.e. influenced – often in a stereotyped way – by head movement. This is manifest in the Hallpike’s test (Information box; Fig. 15.5), which characteristically reveals a rotational nystagmus.

Main causes of vertigo

Stroke

Pathophysiology

What immediate action would you take in this case (i.e. cerebral infarct)?

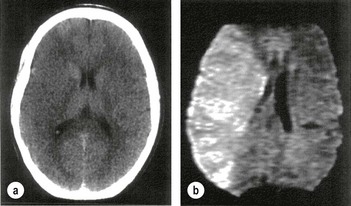

• Is thrombolysis to be considered? Yes. This stroke occurred less than 180 min ago, therefore immediate diffuse weighted MRI (more sensitive than CT) if available should be performed (Fig. 15.6). Unfortunately it was not available for this patient.

• CT will distinguish haemorrhage immediately but infarction cannot be seen early on (Fig. 15.6a).

In this patient the CT showed no evidence of haemorrhage, therefore cerebral infarction was likely.

Other immediate action

Transient ischaemic attack (TIA)

• anterior circulation – sudden transient loss of vision in one eye (amaurosis fugax), aphasia, hemiparesis; or

• posterior circulation – diplopia, ataxia, hemisensory loss, dysarthria, transient global amnesia.

TIAs may herald the onset of stroke (one-quarter of patients developing stroke have had a TIA, usually within the previous week).

The ABCD2 score can help to stratify stroke risk in the first 2 days.

| • Age > 60 years | 1 point |

| • BP > 140 mmHg systolic and/or > 90 mmHg diastolic | 1 point |

| • Clinical features: | |

| Unilateral weakness | 2 points |

| Isolated speech disturbance | 1 point |

| Other | 0 points |

| • Duration of symptoms (min) | |

| > 60 | 2 points |

| 10–59 | 1 point |

| < 10 | 0 points |

| • Diabetes | |

| Present | 1 point |

| Absent | 0 points |

A score of < 4 is associated with a minimal risk, whereas > 6 is high risk for a stroke within 7 days of a TIA.

• If patients are at a high risk of a TIA, i.e. ABCD2 score > 4, or have had two recent TIAs, especially within the same vascular territory, they should be admitted for investigation and treatment (see below).

• All patients should be referred to a TIA clinic and ideally seen within 24 hours. Investigation and treatment should be regarded as urgent and should be completed within 10 days.

Treatment

• Antiplatelet therapy as for stroke (p. 477).

• Modification of vascular risk factors – smoking, hypertension, statins as above.

• Early endarterectomy for symptomatic 70–99% carotid artery stenosis (within 1 week if possible).

• Anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation (p. 274) (aspirin 300 mg daily for 2 weeks, then anticoagulate with heparin and warfarin or dabigatran) (see p. 276).

Brott G, Hobson RW 2nd, Howard G, et al. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:11–23.

Rothwell PM, Algra A, Amarenco P. Medical treatment in acute and long-term secondary prevention after transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke. Lancet. 2011;377:1681–1692.

What are the causes of strokes in this young age group?