OVERVIEW

- The assessment of whether weakness and blackouts are due to a neurological disease process is not easy and usually requires referral to a neurologist. Dizziness is easier to assess in primary care

- The diagnosis of most functional neurological symptoms should be made on the basis of positive evidence in the examination, for example incongruity and inconsistency of limb weakness, not on the absence of disease and normal investigations

- Dizziness can be usefully divided into light-headedness, vertigo and dissociation

- A transparent and effective initial approach to diagnosis, explanation and treatment is possible

Introduction

Around one in six patients referred from primary care to neurology have physical symptoms that turn out not to be due to a disease, which we shall refer to as functional symptoms in this chapter. An additional one in six patients have a mixture of neurological disease and functional symptoms.

Functional neurological symptoms, also known as conversion disorder, psychogenic/non-organic/dissociative neurological symptoms, present a particular challenge in primary care because specialist knowledge and investigations are often required to make the diagnosis. However, the bulk of patient management takes place in primary care and, unfortunately many patients are returned from secondary care without adequate follow-up or treatment. So awareness of how the diagnosis should be made and modes of treatment therefore remain important for all doctors.

Functional weakness

Epidemiology

Functional weakness is one of the commonest causes of limb weakness in patients under the age of 50, with a mean age of onset of 39. It is at least as common as multiple sclerosis. Patients with this diagnosis will, according to studies, turn out to have a disease explanation at follow-up in less than 5% of cases, a frequency that parallels all other neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Clinical features of functional weakness

Patients with functional weakness most commonly complain of weakness of one side of their body, often with a feeling that the limb does not feel part of them; they drop things or their knee keeps giving way. Typically they have a history of other functional symptoms, especially pain, fatigue and concentration problems. In 50% they have a sudden ‘stroke-like’ onset, often with panic, symptoms of dissociation (see below) or a physical injury. The diagnosis should not be based on the presence or absence of stressful life events, which are less common than the name ‘conversion disorder’ suggests.

‘Martin’ is a 41-year-old information technology worker who had been admitted on several occasions to hospital for left-sided weakness. He was discharged with a normal MRI head scan and no diagnosis but continues to feel that something is wrong in his left arm and leg. He also feels unusually tired and can’t concentrate. He wonders if he has been having mini-strokes and is starting to think that doctors don’t believe him. He has a history of anxiety in the past but says that recently he has not been under stress at all.

The diagnosis can be suspected from the history but should only be made on the basis of the physical examination. In this respect functional weakness differs somewhat from symptoms such as pain and fatigue where the examination is much less helpful.

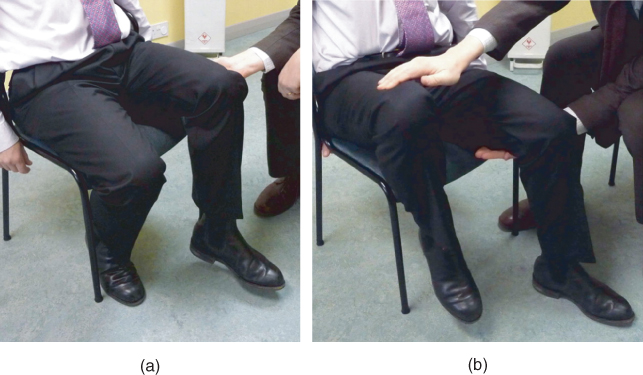

The key finding is of inconsistency of movement, for example a patient who cannot move their ankles on the bed but who can stand on tiptoes and heels. A useful, more repeatable test for patients with leg weakness is Hoover’s sign (Figure 13.1). Although developed as a test to ‘trick’ patients, it can be usefully shared with patients to show them how they have a problem with voluntary movement that improves with distraction (and therefore must be due to a problem in nervous system functioning rather than damage). A dragging gait is also quite specific for more severe functional paralysis (Figure 13.2). Other less reliable pointers to functional weakness include a global pattern of weakness in the limb, sensory disturbance that stops at the shoulder or groin and ‘give way’ weakness in which the limb ‘gives way’ to light pressure but can return to normal with encouragement.

Figure 13.1 Hoovers sign—a clinical sign of functional weakness. (a) Test hip extension – it is weak. (b) Test contralateral hip flexion against resistance – hip extension has become strong.

GP assessment

Limb weakness may, of course, have many causes. The commonest in the age group typically affected are multiple sclerosis and stroke but a large number of rarer conditions need to be considered, which is why referral to a neurologist is usually advisable. Weakness may accompany migraine but should resolve within 24 h.

Referral is usually indicated for functional weakness for several reasons. These are relatively uncommon problems and need skilled assessment. Furthermore some patients may have both functional weakness and a structural ‘organic’ neurological disease and investigation may still be needed.

In referring a patient it may be reasonable to suggest (to patient and specialist) that you suspect a functional disorder and include information about the patient’s psychological state. However, it is wrong to assume either that weakness is functional because of the presence of a psychiatric diagnosis or that it cannot be functional because the patient is psychologically ‘normal’.

Explanation

A helpful explanation for functional weakness includes giving the patient a diagnosis that emphasises that the symptoms are relatively common, genuine and potentially reversible. Explanation alone sometimes leads to recovery. Wherever possible explain to the patient the way in which the diagnosis has been made. The use of metaphor and self-help material (e.g.www.neurosymptoms.org) is often helpful.

You have functional weakness, a common and potentially reversible problem. Your leg is weak when you are trying to move it but the power actually comes back to normal when you are distracted by moving your good leg. This is called Hoover’s Sign. The sign shows that your brain is having trouble sending a message to move to the leg, but the fact it can temporarily return to normal shows it is not damaged. It’s like a software problem on a computer rather than a hardware problem. Its important for you to know that, even though I know this is all a bit strange, I believe you and I don’t think you’re imagining the problem.

Specific treatment

Further treatment may involve psychologically informed physiotherapy/graded exercise for patients with disabling weakness. In the absence of these, encouraging patients to work through a self-help approach and using the principles outlined in this book can be effective.

Blackouts/dissociative (non-epileptic attacks)

Epidemiology

Around one in seven patients attending a ‘first fit’ clinic and up to 50% of patients brought into hospital have a diagnosis of non-epileptic attacks, also called pseudoseizures, psychogenic non-epileptic attacks and dissociative non-epileptic attacks.

Clinical features of dissociative (non-epileptic) attacks

Attacks commonly consist either of generalised shaking, an episode in which the patient suddenly falls down and lies still or a ‘blank spell’.

Patients often do not spontaneously report warning symptoms and rarely report episodes triggered by specific stressful events. With closer questioning, symptoms of panic and dissociation can commonly be found that the patient is reluctant to divulge, partly because they do not want to think about it and partly because they do not want to be considered ‘crazy’.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree