16 Neurological disease

The brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves constitute an organ responsible for perception of the environment, a person’s behaviour within it, and the maintenance of the body’s internal milieu in readiness for this behaviour. In the UK some 10% of the population consult their GP each year with a neurological symptom, and neurological disorders account for about one-fifth of acute medical admissions and a large proportion of chronic physical disability.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS

HEADACHE

SUBACUTE HEADACHE

Headache coming on over the course of hours is likely to be migraine, unless accompanied by other symptoms or signs. Migraine headaches may be accompanied or preceded by vomiting and focal neurological symptoms. Patients with bacterial meningitis are usually pyrexial and exhibit meningism (p. 664). Patients with viral meningitis may present with a pyrexia and quite sudden and severe headache, but may not have meningism.

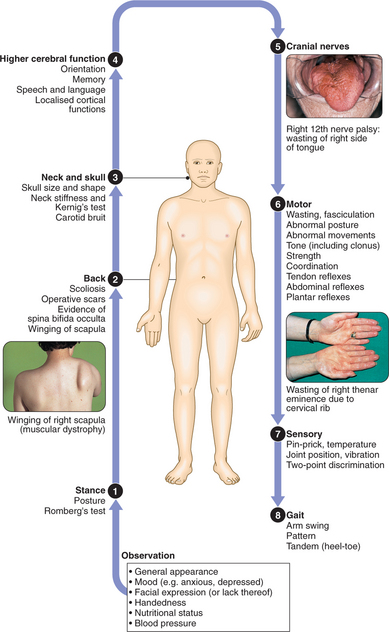

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

TENSION-TYPE HEADACHE

MIGRAINE

Clinical assessment

Migraine is a triad of paroxysmal headache, nausea and/or vomiting, and an ‘aura’ of focal neurological events. Patients with all three features have migraine with aura (‘classical’ migraine). Migraine without aura, with or without vomiting, is called ‘common’ migraine. A classical migraine attack starts with a prodrome of malaise and irritability followed by the ‘aura’ of a focal neurological event, and then a severe, throbbing, hemicranial headache with photophobia and vomiting. The headache may persist for several days.

The aetiology of migraine is largely unknown.

CLUSTER HEADACHE (MIGRAINOUS NEURALGIA)

TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA

Clinical assessment

DIZZINESS, BLACKOUTS AND ‘FUNNY TURNS’

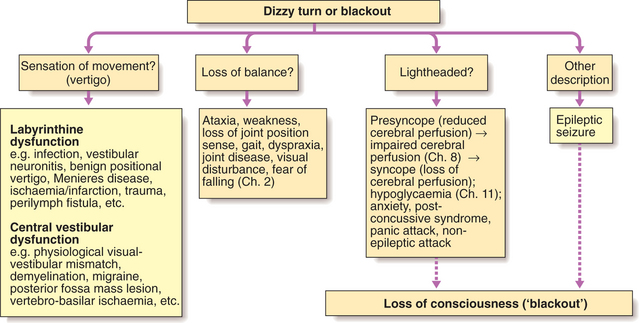

Episodes of lost or altered consciousness are frequent. After a careful history from the patient, supplemented by a witness account, it should be clear whether the patient is describing loss of consciousness, altered consciousness, vertigo, transient amnesia or something else. The diagnostic approach is shown in Figure 16.1.

EPISODIC LOSS OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Transient loss of consciousness occurs because of a recoverable loss of adequate blood supply to the brain (syncope), or from sudden electrical dysfunction of the brain during a seizure (epileptic fit). Many patients have psychogenic blackouts or non-epileptic seizures which may confuse this distinction. No amount of investigation can replace a clear history in these circumstances. Features in the history useful in distinguishing a seizure from a faint are shown in Box 16.1.

16.1 FEATURES HELPFUL IN DISTINGUISHING SEIZURES FROM FAINTS ![]()

| Seizure | Faint | |

|---|---|---|

| Aura (e.g. olfactory) | + | – |

| Cyanosis | + | – |

| Tongue-biting | + | – |

| Post-ictal confusion | + | – |

| Post-ictal amnesia | + | – |

| Post-ictal headache | + | – |

| Rapid recovery | – | + |

SYNCOPE

A brief feeling of ‘lightheadedness’ often precedes a faint; vision then darkens and there may be a ringing in the ears. Vasovagal syncope (p. 211) may be provoked by some emotionally charged event (e.g. venepuncture) and usually occurs while standing. Cardiac syncope, caused by a sudden decline in cardiac output and hence cerebral perfusion, may be exertional (e.g. with severe aortic stenosis) or may occur completely ‘out of the blue’ (as in heart block). During a syncopal attack, incontinence of urine can occur and there is often stiffening and brief twitching of the limbs, but tongue-biting never occurs. Recovery is rapid and without confusion.

SEIZURES

Clinical assessment

Partial motor seizures: Epileptic activity in the pre-central gyrus causes partial motor seizures affecting the contralateral face, arm, trunk or leg. There is rhythmical jerking or sustained spasm of the affected parts. They may remain localised to one part, or may spread to involve the whole side. Some attacks begin in one part and spread gradually (‘Jacksonian epilepsy’). Prolonged episodes may leave paresis of the involved limb lasting for several hours (Todd’s palsy).

EPILEPSY

Investigations

EEG: May be more helpful in showing focal features if performed very soon after a seizure than after an interval. It can also help establish the type of epilepsy and guide therapy.

Management

Immediate care of seizures: Little can or need be done for a person whilst a major seizure is occurring except first aid and common-sense manoeuvres (Box 16.2).

16.2 IMMEDIATE CARE OF SEIZURES ![]()

First aid (by relatives and witnesses)

Anticonvulsant drug therapy (see also p. 781): Drug treatment should be considered after more than one seizure has occurred. Of patients whose epilepsy is controllable, only a single drug is necessary in 80%. Dose regimens should be kept as simple as possible to promote compliance. The first line of treatment should be one of the established drugs (Box 16.3), with more recently introduced drugs as second choice. Try up to three agents singly before resorting to combinations; beware drug interactions. Phenytoin and carbamazepine induce liver enzymes and therefore are not ideal for women wishing to use oral contraception. Occasional phenytoin and carbamazepine blood levels can be checked to confirm appropriate dose and to check compliance. There is no relationship between drug levels of sodium valproate and anticonvulsant efficacy.

16.3 GUIDELINES FOR CHOICE OF ANTI-EPILEPTIC DRUGS ![]()

| Epilepsy type | First-line | Second-line |

|---|---|---|

| Partial and/or secondary GTCS | Carbamazepine | |

| Primary GTCS | Sodium valproate | |

| Absence | Ethosuximide | Sodium valproate |

| Myoclonic | Sodium valproate | Clonazepam |

N.B. Preferably one and no more than two drugs should be used at one time. (GTCS = generalised tonic clonic seizure.)

STATUS EPILEPTICUS

Status epilepticus exists when a series of seizures occurs over 30 mins without the patient regaining awareness between attacks. This usually refers to recurrent tonic clonic seizures and is a medical emergency. Status is never the presenting feature of idiopathic epilepsy but may be precipitated by abrupt withdrawal of anticonvulsant drugs, a major structural lesion or acute metabolic disturbance. Management is summarised in Box 16.4.

16.4 MANAGEMENT OF STATUS EPILEPTICUS ![]()

Pharmacological

If seizures continue after 30 mins

If seizures still continue after 30–60 mins

SLEEP DISORDERS

Disturbances of sleep are common. Apart from insomnia, patients may complain of:

DISORDERS OF MOVEMENT

THE MOTOR SYSTEM

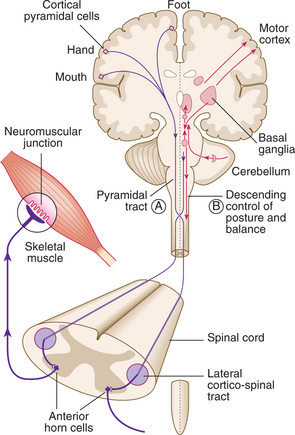

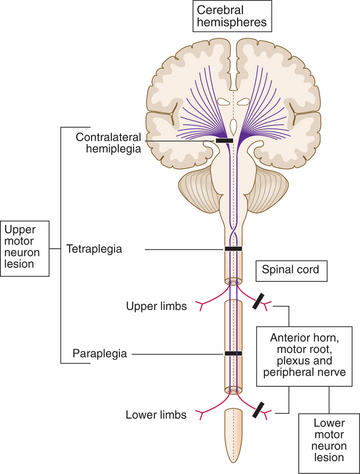

A programme of movement formulated by the pre-motor cortex is converted into a series of muscle movements in the motor cortex and then transmitted to the spinal cord in the pyramidal tract (Fig. 16.2).

Upper motor neuron (pyramidal) lesions: When the spinal cord is disconnected from the higher motor hierarchies, the anterior horn motor neurons are under the uninhibited influence of the spinal reflex mechanisms. An upper motor neuron lesion therefore manifests clinically with brisk tendon stretch reflexes, ‘spastic’ increase in tone, and extensor plantar responses. Spasticity takes time to develop and may not be present for weeks.

Extrapyramidal lesions: There is an increase in tone, which is continuous throughout the range of movement at any speed of stretch (‘lead-pipe’ rigidity). Involuntary movements are present, and a tremor combined with rigidity produces typical ‘cogwheel’ rigidity. Rapid movements are slowed (bradykinesia). Extrapyramidal lesions also cause postural instability, precipitating falls.

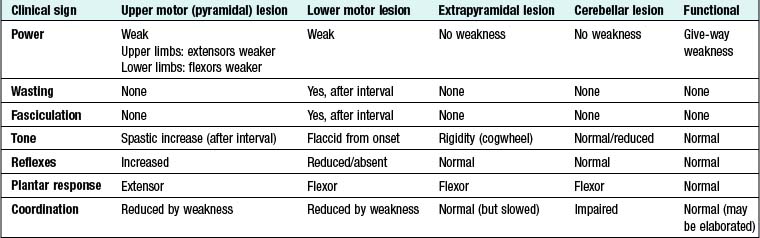

A DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH TO LIMB WEAKNESS (Box 16.5, Fig. 16.3)

16.6 LIMB WEAKNESS: ASSESSING THE CAUSE ![]()

| Vascular (stroke) lesions | Sudden onset (over mins) followed by a stable period and gradual recovery |

| Neoplastic lesions | |

| Inflammatory lesions | May be fairly acute (over days), persist for a time and then improve (e.g. MS) |

| Degenerative disorders | May evolve over mths/yrs (e.g. motor neuron disease or cervical myelopathy) |

GAIT DISORDERS

Cerebellar ataxia: Patients with lesions of the central parts of the cerebellum (the vermis) walk with a characteristic broad-based gait, ‘like a drunken sailor’.

Extrapyramidal gait: Patients have difficulty initiating walking and controlling the pace of their gait. This produces the festinant gait: initial stuttering steps that quickly increase in frequency while decreasing in length.

INVOLUNTARY MOVEMENTS

Action tremor: More common than rest tremor. The potential causes are numerous:

Ballism: More dramatic than chorea, ballistic movements of the limbs usually occur unilaterally (hemiballismus) in vascular lesions of the subthalamic nucleus.

SENSORY DISTURBANCE

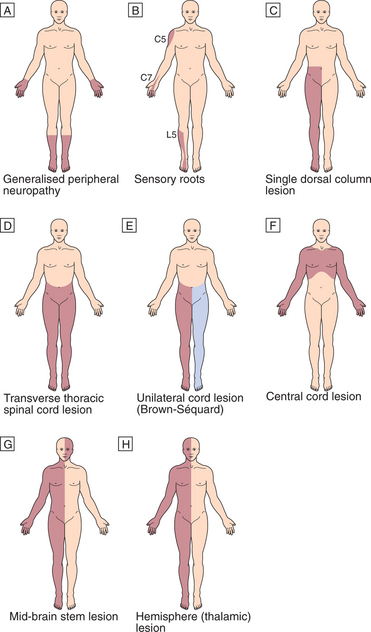

PATTERNS OF SENSORY DISTURBANCE (Fig. 16.4)

Peripheral nerve lesions

In peripheral nerve lesions, the symptoms are usually of sensory loss and simple paraesthesia (pins and needles). Single peripheral nerve lesions will cause disturbance in the sensory distribution of that nerve. In diffuse neuropathies the longest neurons are affected first, giving the characteristic ‘glove and stocking’ distribution.

Spinal cord lesions

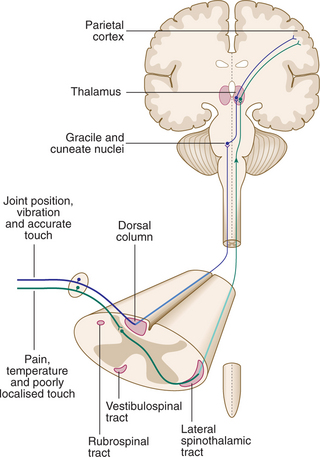

Sensory information ascends the nervous system in two anatomically discrete systems, differential involvement of which is often of diagnostic assistance (Fig. 16.5).

Transverse spinal cord lesions: There is loss of all modalities below that segmental level. Often a band of paraesthesia or hyperaesthesia is found at the top of the area of loss. If vascular in origin (e.g. due to anterior spinal artery thrombosis), the posterior one-third of the spinal cord (dorsal column modalities) may be spared.

COMA AND BRAIN DEATH

COMA

Persistent loss of consciousness or coma indicates disorder of the arousal mechanisms in the brain stem and diencephalon. There are many causes of coma (Box 16.7). The history is crucial to establishing the cause and should be obtained from any witnesses. Neurological examination may reveal important findings, e.g. evidence of head injury, papilloedema, meningism or eye movement disorder.

16.7 CAUSES OF COMA ![]()

| Metabolic disturbance | Drug overdose, diabetes mellitus (hypoglycaemia, ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar coma), hyponatraemia, uraemia, liver failure, respiratory failure, hypothermia, hypothyroidism |

| Trauma | Cerebral contusion, extradural haematoma, subdural haematoma |

| Cerebrovascular disease | Subarachnoid haemorrhage, intracerebral haemorrhage, brain-stem infarction/haemorrhage, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis |

| Infections | Meningitis, encephalitis, cerebral abscess, general sepsis |

| Others | Epilepsy, brain tumour, thiamine deficiency |

Assessment of conscious level

Systematic assessment using the Glasgow Coma Scale provides a grading of coma which allows serial comparison and may provide prognostic information, particularly in traumatic coma (Box 16.8).

16.8 GLASGOW COMA SCALE ![]()

| Eye-opening (E) | |

| 4 | |

| 3 | |

| 2 | |

| 1 | |

| Best motor response (M) | |

| 6 | |

| 5 | |

| 4 | |

| 3 | |

| 2 | |

| 1 | |

| Verbal response (V) | |

| 5 | |

| 4 | |

| 3 | |

| 2 | |

| 1 | |

| Coma score = E + M + V | |

| 3 | |

| 15 | |

ACUTE CONFUSIONAL STATE (DELIRIUM)

This is much more common than dementia. Unlike in dementia, there is a disturbance of arousal that accompanies the global impairment of mental function. There is drowsiness with disorientation, perceptual disturbances and muddled thinking. Patients typically fluctuate, confusion being worse at night, and there may be associated emotional disturbance or psychomotor changes. There are many possible causes (Box 16.9).

16.9 CAUSES OF ACUTE CONFUSIONAL STATE ![]()

| Type | Common | Unusual |

|---|---|---|

| Infective | ||

| Metabolic/endocrine | ||

| Vascular | ||

| Toxic | ||

| Neoplastic | Secondary deposits | |

| Trauma | Cerebral contusion, subdural haematoma | |

| Other |

Diagnosis

It is vital to take a history from a witness. Examination may yield other clues. It is important to distinguish confusion from a fluent aphasia. Often, however, the cause is not immediately obvious and a wide screen of tests must be performed (Box 16.10).

16.10 INVESTIGATION OF ACUTE CONFUSIONAL STATE ![]()

| First-line | Other useful tests | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood tests | ||

| CNS tests | Head imaging (CT and/or MRI) | Lumbar puncture, EEG |

| Other |

DISTURBANCE OF MEMORY

CHANGES IN PERSONALITY AND BEHAVIOUR

DISORDERS OF PERCEPTION

The parietal lobes are also involved in the higher processing and integration of primary sensory information. Damage here gives rise to sensory (including visual) inattention and apraxia. Apraxia is the inability to perform complex, organised activity in the presence of a normal basic motor, sensory and cerebellar system (e.g. dressing, using cutlery and finding one’s way around geographically).

PROBLEMS WITH BRAIN-STEM FUNCTION

SWALLOWING DIFFICULTIES

DISORDERS OF BALANCE

Disorders of balance can arise from a number of different abnormalities affecting:

VISUAL DISTURBANCE

VISUAL LOSS

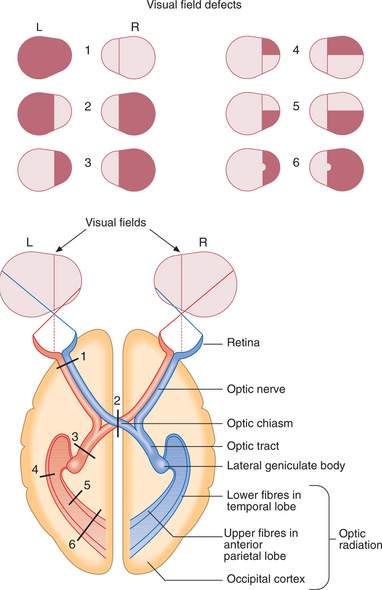

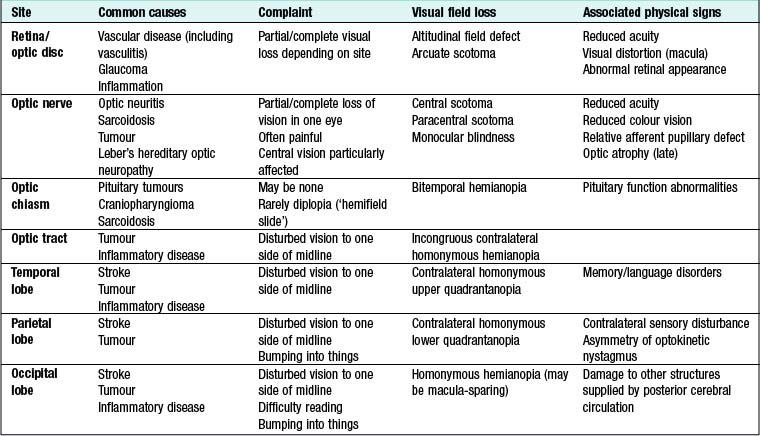

The visual pathway from the retina to the occipital cortex is topographically organised, so the pattern of visual field loss allows localisation of the site of the lesion (Fig. 16.6, Box 16.11). Patients often present with transient visual loss.

EYE MOVEMENT DISORDERS

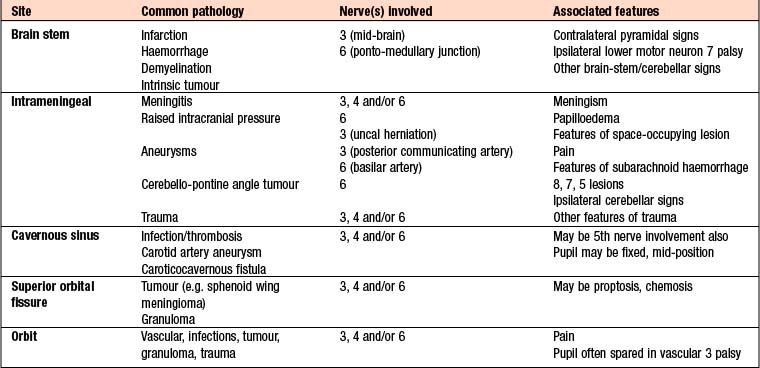

Diplopia (‘double vision’)

The pattern of double vision and associated features allow localisation of the lesion, whilst the mode of onset and subsequent behaviour suggest the aetiology. The trochlear (4th) nerve innervates the superior oblique muscle, and the abducens (6th) nerve innervates the lateral rectus. The oculomotor (3rd) nerve innervates the remainder of the extraocular muscles along with the levator palpebrae superioris and the ciliary body (pupil constriction and accommodation). Causes of ocular motor nerve palsies are given in Box 16.12.