(1)

Department of Pathology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

Keywords

GanglioneuromaGanglioneuroblastomaNeuroblastomaPeripheral nerve sheath tumorsSchwannomaNeurofibromaMalignant peripheral nerve sheath tumorMalignant schwannomaPrimitive neuroectodermal tumorNeurogenic tumors of the mediastinum are relatively rare and are most often encountered in the pediatric-age population. They most commonly arise from structures in the posterior mediastinum, although they can originate from all three mediastinal compartments. Neurogenic tumors are, in fact, the most common tumors of the posterior mediastinum in both children and adults. Neurogenic tumors can be of neuroblastic origin or may arise from peripheral nerve sheath elements (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1

Neurogenic tumors of the mediastinum

Neuroblastic tumors |

Ganglioneuroma |

Ganglioneuroblastoma |

Neuroblastoma |

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors |

Schwannoma |

Neurofibroma |

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor |

4.1 Neuroblastic Neoplasms

Neuroblastic neoplasms (Figs. 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 4.5, 4.6, 4.7, 4.8, 4.9, 4.10, 4.11, 4.12, 4.13, 4.14, 4.15, 4.16, 4.17, 4.18, 4.19, 4.20, 4.21, 4.22, 4.23, 4.24, 4.25, 4.26, 4.27, 4.28, 4.29, 4.30, 4.31, and 4.32) arise from primitive precursor cells of the sympathetic nervous system. They are the most common solid tumors in children under 1 year of age, although they can also occur in older children and in adults. Some cases can be associated with neurofibromatosis (NF1). They show a histologic spectrum that ranges from very well-differentiated and mature neuronal elements to tumors composed of primitive and poorly differentiated cells, mimicking the entire spectrum of neuroblastic maturation.

Fig. 4.1

Neuroblastic tumors are most often large and solid, well circumscribed, and surrounded by a fibrous capsule. They usually show a smooth outer surface. This image is an example of a ganglioneuroma, the most common benign tumor originating from the thoracic sympathetic nerves

Fig. 4.2

Ganglioneuromas are benign neurogenic tumors composed of mature neural elements admixed in varying proportions. They are often paucicellular and show a variously collagenized stroma on scanning magnification

Fig. 4.3

On higher magnification, ganglioneuromas are composed mainly of loose, fibrocollagenous stroma admixed with bland-appearing fibroblastic or schwannian spindle cells. The stroma may vary from loose and edematous to densely collagenized. Based on the extent of the schwannian component, they have been classified into schwannian stroma dominant (“mature” ganglioneuroma) and schwannian stroma poor (“maturing” ganglioneuroma)

Fig. 4.4

Schwannian stroma-poor ganglioneuroma shows a focus (center) containing large ganglion cells with abundant cytoplasm and round nuclei that are intimately admixed in various proportions with the spindle cells and collagenous stroma

Fig. 4.5

Higher magnification from the field in Fig. 4.4 shows a cluster of large ganglion cells with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and large, round nuclei

Fig. 4.6

Schwannian stroma-rich mediastinal ganglioneuroma shows clusters of large ganglion cells with small, round nuclei surrounded by abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm embedded in a dense collagenous stroma containing abundant schwannian spindle cells

Fig. 4.7

Higher magnification of schwannian stroma-rich ganglioneuroma showing large ganglion cells with eccentric nuclei

Fig. 4.8

Higher magnification of ganglion cells in ganglioneuroma showing characteristic small nuclei surrounded by abundant pink granular cytoplasm. The number of ganglion cells in these tumors may vary; if they are very sparse, proper identification may require a diligent search

Fig. 4.9

Ganglioneuroblastoma is a tumor characterized by an admixture in various proportions of both mature schwannian and ganglionic elements, as well as primitive neuroblastic elements that form discrete nests or islands of tumor cells. The tumors are grossly well circumscribed, with a fleshy, tan-white cut surface with focal areas of cystic degeneration and foci of calcification

Fig. 4.10

Histologically, ganglioneuroblastoma shows areas that are indistinguishable from ganglioneuroma in association with foci of neuroblastic elements. The neuroblastic elements are arranged in discrete, small nests of primitive neuroblastic cells (lower right) that merge with the schwannian-rich stroma (left)

Fig. 4.11

Higher magnification from the field in Fig. 4.10 shows bland-appearing schwannian spindle cells (left) percolating between small nests of small neuroblastic cells (right)

Fig. 4.12

Schwannian stroma-poor ganglioneuroblastoma shows a paucicellular, collagenous stroma merging imperceptibly with islands and nests of primitive, small neuroblastic cells admixed with larger ganglionic cells

Fig. 4.13

Higher magnification of schwannian stroma-poor ganglioneuroblastoma shows a mixed cell population composed of small, primitive neuroblastic cells admixed with larger ganglionic cells

Fig. 4.14

Another example of ganglioneuroblastoma shows a few small nests containing neuroblastic elements surrounded by a schwannian-rich spindle-cell stroma

Fig. 4.15

Higher magnification of ganglioneuroblastoma showing a mixed population of neuroblastic small cells admixed with larger ganglionic cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm

Fig. 4.16

Ganglioneuroblastoma with foci of dystrophic calcifications. Neuroblastoma elements occasionally undergo dystrophic calcification that replaces the tumor cells. The presence of these foci of calcification is an indication of a neuroblastic component in the tumor and should prompt search of additional sections

Fig. 4.17

Neuroblastoma is the most common malignant neoplasm of the posterior mediastinum in children, particularly under the age of 1 year. Grossly, the tumors are well circumscribed and encapsulated, with a multinodular outer surface

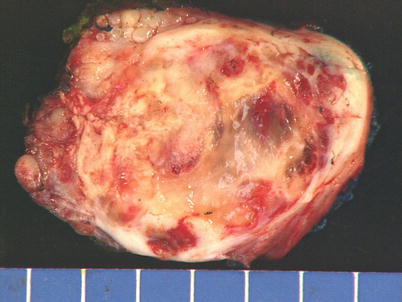

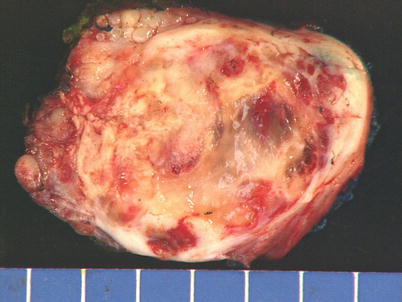

Fig. 4.18

Cut surface of a neuroblastoma shows grayish white, soft tissue with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis and foci of calcification

Fig. 4.19

Histologically, neuroblastoma is composed of a proliferation of small, round blue cells showing various degrees of organization. Neuroblastomas have been classified into differentiating, poorly differentiated, and undifferentiated, depending on their degree of maturation and organization. The well-differentiated tumors (differentiating neuroblastoma) overlap with ganglioneuroblastoma but show a predominance of neuroblastic elements over ganglionic cells and may also contain a minor schwannian component. The poorly differentiated variants show no evidence of ganglionic or schwannian differentiation and grow as sheets of small tumor cells that often present a nested appearance, as in this example

Fig. 4.20

Higher magnification from Fig. 4.19 shows well-defined islands or nests of tumor cells separated by a vascular stroma

Fig. 4.21

Higher magnification showing well-defined nests of tumor cells with abundant fibrillary eosinophilic material (neuropil) in the background. The fibrillary material (neuropil) is a distinctive feature of neuroblastic neoplasms and helps in the differential diagnosis with other small, round cell tumors

Fig. 4.22

Another area in the same tumor shows a peculiar linear, single-file arrangement of neuroblastic cells embedded in abundant fibrillary matrix, a feature often observed in these tumors

Fig. 4.23

Extensive stromal calcification is a common feature in neuroblastoma. The calcifying process can be so extensive as to obscure the underlying neoplastic proliferation; recognition of the tumor cells may then require extensive sampling

Fig. 4.24

Higher magnification in calcifying neuroblastoma shows irregular deposits of calcific material surrounded by proliferation of primitive, small, round blue cells

Fig. 4.25

Higher magnification shows small nests of tumor cells admixed with calcific stromal deposits. The tumor cells show a primitive appearance with small, round nuclei with tiny nucleoli and no discernible cytoplasm

Fig. 4.26

Another example of differentiating neuroblastoma on scanning magnification shows a lobular growth pattern separated by well-vascularized stroma and foci of stromal calcifications

Fig. 4.27

Higher magnification shows a lobule of tumor cells with abundant background neuropil and a mixed cell population, including ganglionic-type large cells and scattered smaller neuroblastic cells

Fig. 4.28

High power shows a scant amount of tumor cells displaying various degrees of maturation, floating in abundant eosinophilic fibrillary matrix (neuropil)

Fig. 4.29

This neuroblastoma of an “undifferentiated” type shows almost solid sheets of small, round, primitive cells with only a vague hint of nesting

Fig. 4.30

Higher magnification from the same case as Fig. 4.29 shows a primitive population of small, round, blue cells growing as sheets with scattered mitoses. The tumor cells have small, irregular nuclei with scant nuclear detail and small nucleoli

Fig. 4.31

Higher magnification shows the presence of Flexner-type rosettes, another distinctive feature sometimes seen in poorly differentiated neuroblastoma

Fig. 4.32

Immunohistochemistry can aid in the differential diagnosis of neuroblastoma, particularly the poorly differentiated and undifferentiated forms. Neuron-specific enolase (pictured) and other neuronal markers (synaptophysin, chromogranin, neurofilament protein, etc.) are generally positive in the tumor cells, to the exclusion of other specific markers of differentiation (keratins, desmin, actin, S-100 protein, etc.). Molecular genetics also plays a role, as alterations such as overexpression of MYCN and chromosome 1p deletion have been associated with more aggressive behavior and can serve as markers for the more poorly differentiated tumors

4.2 Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors (PNSTs) are the most commonly encountered tumors in the posterior mediastinum. These can also show a wide spectrum of differentiation ranging from benign, fully differentiated neural tumors (schwannoma, Figs. 4.33, 4.34, 4.35, 4.36, 4.37, 4.38, 4.39, 4.40, 4.41, 4.42, 4.43, 4.44, 4.45, 4.46, 4.47, 4.48, 4.49, 4.50, 4.51, 4.52, 4.53, 4.54, 4.55, 4.56, 4.57, 4.58, and 4.59) to tumors showing a prominent fibroblastic component (neurofibroma, Figs. 4.60, 4.61, 4.62, and 4.63) to poorly differentiated malignant neural neoplasms (malignant PNSTs, Figs. 4.64, 4.65, 4.66, 4.67, 4.68, 4.69, 4.70, 4.71, 4.72, 4.73, 4.74, 4.75, and 4.76). The tumors most often affect young to middle-aged adults and are commonly seen in a paravertebral location. Some tumors may adopt a dumbbell configuration and penetrate into the spinal canal.