Chapter 31 Neoplastic disease and immunosuppression

Neoplastic disease

Cancer treatments and outcomes

Cancers share some common characteristics:

• Growth that is not subject to normal spatial restrictions for that tissue and fails to respond to apoptotic signals (see below) or in which a high proportion of cells are dividing, i.e. there is a high ‘growth fraction’.

• Tendency to spread to other parts of the body (metastasise).

• Less differentiated cell morphology.

• Tendency to retain some characteristics of the tissue of origin, at least initially.

Cancer treatment employs six established principal modalities:

This account describes the main groups of drugs (see p. 510) but it is important to understand the overall context in which systemic therapy is offered to patients.

Systemic cancer therapy

Cancers originating from different organs of the body differ in their initial behaviour and in their response to treatments (Table 31.1). Primary surgery and/or radiotherapy to a localised cancer offer the best chance of cure for patients. Drug treatments offer cure only for certain types of cancer, often characterised by their high proliferative rate, e.g. lymphoma, testicular cancer, Wilms’ tumour. More often, systemic therapy offers prolongation of life from months to many years and associated improvements in quality of life, even if patients ultimately die from their disease.

Table 31.1 Degree of benefit achieved with systemic therapy for common cancers

| Curable: chemosensitive cancers | Improved survival: some degree of chemosensitivity | Equivocal survival benefit: chemoresistant cancers |

|---|---|---|

| Teratoma | Colorectal cancer | Sarcoma |

| Seminoma | Small cell lung cancer | Bladder cancer |

| High-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Ovarian cancer | Melanoma |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Breast cancer | Renal cancer Insensitive to cytotoxic chemotherapy but now can be controlled temporarily with oral VEGF2 and mTOR inhibitors |

| Wilms’ tumour | Cervical cancer | Primary brain cancers |

| Acute myeloblastic leukaemia | Endometrial cancer | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in childhood | Gastro-oesophageal cancer Cholangiocarcinoma and gall bladder cancer | Hepatoma Insensitive to cytotoxic chemotherapy but now can be controlled temporarily with oral VEGF inhibitors |

| Myeloma | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | ||

| Low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | ||

| Non-small cell lung cancer | ||

| Adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia |

Classes of cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs

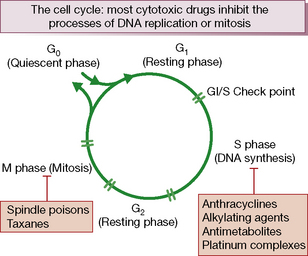

Cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs exert their effect by inhibiting cell proliferation. All proliferating cells, whether normal and malignant, cycle through a series of phases of: synthesis of DNA (S phase), mitosis (M phase) and rest (G1 phase). Non-cycling cells are quiescent in G0 phase (Fig. 31.1).

They are thus all potentially mutagenic. Cytotoxic drugs ultimately induce cell death by apoptosis,2 a process by which single cells are removed from living tissue by being fragmented into membrane-bound particles and phagocytosed by other cells. This occurs without disturbing the architecture or function of the tissue, or eliciting an inflammatory response. The instructions for apoptosis are built into the cell’s genetic material, i.e. ‘programmed cell death’.3

Cytotoxic drugs can be classified as either:

• cell cycle non-specific: these kill cells whether they are resting or actively cycling (as in a low growth fraction cancer such as solid tumours), e.g. alkylating agents, doxorubicin and allied anthracyclines, or

• cell cycle (phase) specific: these kill only cells that are actively cycling, often because their site of action is confined to one phase of the cell cycle, e.g. antimetabolite drugs.

Table 31.2 provides a summary of the key groups of anticancer drugs, their common toxicities and main treatment applications.

Table 31.2 Principal classes of cytotoxic drug, their common toxicities and examples of clinical use

| Drug class | Common toxicities | Examples of clinical use |

|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxic drugs | ||

| Alkylating agents | Nausea and vomiting, bone marrow depression (delayed with carmustine and lomustine), cystitis (cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide), pulmonary fibrosis (especially busulfan). Male infertility and premature menopause may occur. Myelodysplasia and secondary neoplasia | Widely used in the treatment of both haematological and non-haematological cancers, with varying degrees of success |

| Platinum drugs | Bone marrow depression, nausea and vomiting, allergy reaction (esp. carboplatin), nephrotoxicity, hypomagnesaemia; hypocalcaemia; hypokalaemia; hypophosphataemia; hyperuricaemia (all as a consequence of renal dysfunction, primarily associated with cisplatin); Raynaud’s disease; sterility; teratogenesis; ototoxicity (cisplatin); peripheral neuropathy; cold dysaesthesia and pharyngolaryngeal dysaesthesia (oxaliplatin) | Testicular cancers, ovarian cancer; oxaliplatin acts synergistically with 5FU and is licensed in combination with 5FU to treat both advanced and early stages of colorectal cancer |

| Nucleoside analogues, e.g. cytarabine, gemcitabine, fludarabine | Bone marrow depression, mainly affecting platelets; mild nausea and vomiting; diarrhoea; anaphylaxis; sudden respiratory distress with high doses (cytarabine); rash, fluid retention and oedema; profound immunosuppression with fludarabine | Cytarabine is used in haematological regimens; gemcitabine is used for pancreatic cancer, bladder cancer and some other solid tumours; fludarabine is active in chronic lymphatic leukaemia and lymphoma |

| Taxanes | Nausea and vomiting, hypersensitivity reactions, bone marrow depression, fluid retention; peripheral neuropathy; alopecia; arthralgias; myalgias; cardiac toxicity; mild GI disturbances; mucositis | Breast and gynaecological cancers; recent evidence that docetaxel improves survival in advanced prostate cancer |

| Anthracyclines | Nausea and vomiting, bone marrow depression; cardiotoxicity (may be delayed for years); red-coloured urine; severe local tissue damage and necrosis on extravasation; alopecia; stomatitis; anorexia; conjunctivitis; acral (extremities) pigmentation; dermatitis in previously irradiated areas; hyperuricaemia | Common component of many chemotherapy regimens for both haematological and non-haematological malignancies |

| Antimetabolites, e.g. 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate | Nausea and vomiting; diarrhoea; mucositis, bone marrow depression, neurological defects, usually cerebellar; cardiac arrhythmias; angina pectoris, hyperpigmentation, hand–foot syndrome, conjunctivitis | Commonly used in haematological and non-haematological malignancies |

| Topoismerase I inhibitors | Nausea and vomiting; cholinergic syndrome; hypersensitivity reactions; bone marrow depression; diarrhoea; colitis; ileus; alopecia; renal impairment; teratogenic | Irinotecan is effective in advanced colorectal cancer; topotecan is used in gynaecological malignancies |

| Mitotic spindle inhibitors (vinca alkaloids) | Nausea and vomiting; local reaction and phlebitis with extravasation, neuropathy, bone marrow depression; alopecia; stomatitis; loss of deep tendon reflexes; jaw pain; muscle pain; paralytic ileus | Commonly used in haemato-oncology regimens |

| Hormones | ||

| Tamoxifen | Hot flushes; transiently increased bone or tumour pain; vaginal bleeding and discharge; rash; thromboembolism; endometrial cancer | Oestrogen receptor-positive, advanced and early stage breast cancer |

| Aromatase inhibitors | Nausea; dizziness; rash; bone marrow depression; fever; masculinisation | Equivalence with tamoxifen suggested |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | Menstrual changes; gynaecomastia; hot flushes; oedema, weight gain; hirsutism; insomnia; fatigue; depression; thrombophlebitis and thromboembolism; nausea; urticaria; headache | Third-line therapy for slowly progressive breast cancer in postmenopausal women |

| Flutamide | Nausea; diarrhoea; gynaecomastia; hepatotoxicity | Prostate cancer |

| Goserelin | Transient increase in bone pain and urethral obstruction in patients with metastatic prostatic cancer; hot flushes; impotence; testicular atrophy; gynaecomastia | Prostate cancer |

| Leuprolelin (LHRH analogue) | Transient increase in bone pain and ureteral obstruction in patients with metastatic prostatic cancer; hot flushes, impotence; testicular atrophy; gynaecomastia; peripheral oedema | Prostate cancer |

| Immunotherapy | ||

| BCG (bacille Calmette-Guérin) | Bladder irritation; nausea and vomiting; fever; sepsis, granulomatous pyelonephritis; hepatitis; urethral obstruction; epididymitis; renal abscess | Localised bladder cancer |

| Interferon-α | Fever; chills; myalgias; fatigue; headache; arthralgias, bone marrow depression; anorexia; confusion; depression; psychiatric disorders; renal toxicity; hepatic toxicity; rash | Renal cancer |

| Interleukin-2 | Fever; fluid retention; hypotension; respiratory distress; rash; anaemia, thrombocytopenia; nausea and vomiting; diarrhoea, capillary leak syndrome, nephrotoxicity; myocardial toxicity; hepatotoxicity; erythema nodosum; neuropsychiatric disorders; hypothyroidism; nephrotic syndrome | Renal cancer |

| Trastuzumab (Herceptin) | Fever; chills; nausea and vomiting; pain; hypersensitivity and pulmonary reactions, bone marrow depression; cardiomyopathy; ventricular dysfunction; congestive cardiac failure; diarrhoea | Advanced and early stage breast cancer, combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy |

| Rituximab (MabThera) | Hypersensitivity reaction, bone marrow depression, angioedema, precipitation of angina or arrhythmia with pre-existing heart disease | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

Adverse effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy

Principal adverse effects are manifest as, or follow damage to, the following:

may occur within hours of treatment or be delayed, and last for several days, depending on the agent. As emetogenicity is largely predictable, preventive action can be taken. The most effective drugs are competitive antagonists of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine type 3, 5HT3) receptors, e.g. ondansetron, and corticosteroids such as dexamethasone, which benefit by unknown, multi-factorial mechanisms. Other effective antiemetics include domperidone, metoclopramide, cyclizine and prochlorperazine (see p. 534). Combinations of drugs are frequently used and routes of administration selected as commonsense counsels, e.g. prophylaxis may be oral, but when vomiting occurs the parenteral route and suppositories are available.