Introduction

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a gastrointestinal (GI) infectious disease most often experienced by preterm neonates. NEC is characterized by ischemia within any part of the intestine usually involving the terminal ileum. Although the exact mechanisms leading to NEC are unknown, the disease state is related to the interplay of intestinal flora, intestinal perfusion, enteral nutrition, and stress.1

Epidemiology

With neonatal care advances and increased survival in preterm neonates, the incidence of NEC has increased. The median onset is 10 days after birth. Fifty percent of NEC occurrences are in neonates with birth weights less than 1.5 kg. Eighty percent of cases occur in neonates weighing less than 2.5 kg at birth.2 Neonates weighing less than 1.5 kg at birth have an incidence of 6 to 12%,3,4 and one-third of them with a diagnosis of NEC will die.4 Overall mortality rates range from 10 to 50%.5

Pathophysiology

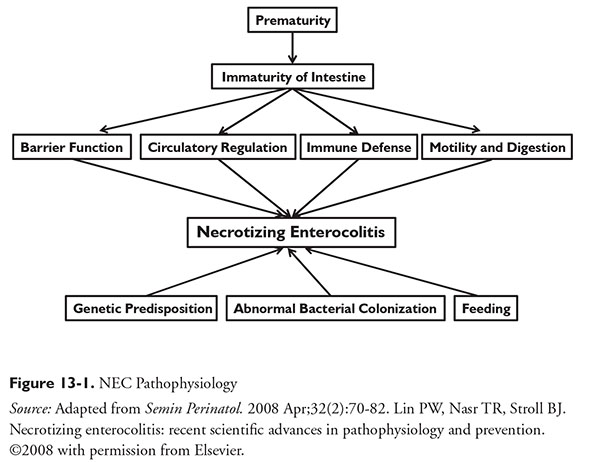

The pathophysiology of NEC is multifactorial and not fully understood. The underlying hypothesis for NEC is unregulated inflammatory responses to colonization of bacteria within the intestine.4 NEC may be a response by an immature GI tract to an injury.6 Feeding strategy and genetic predisposition may also contribute (Figure 13-1).7

Presentation

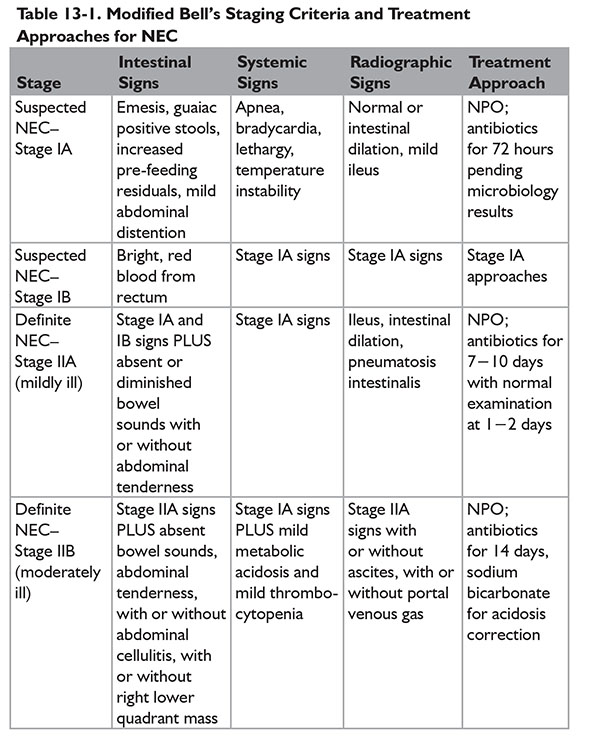

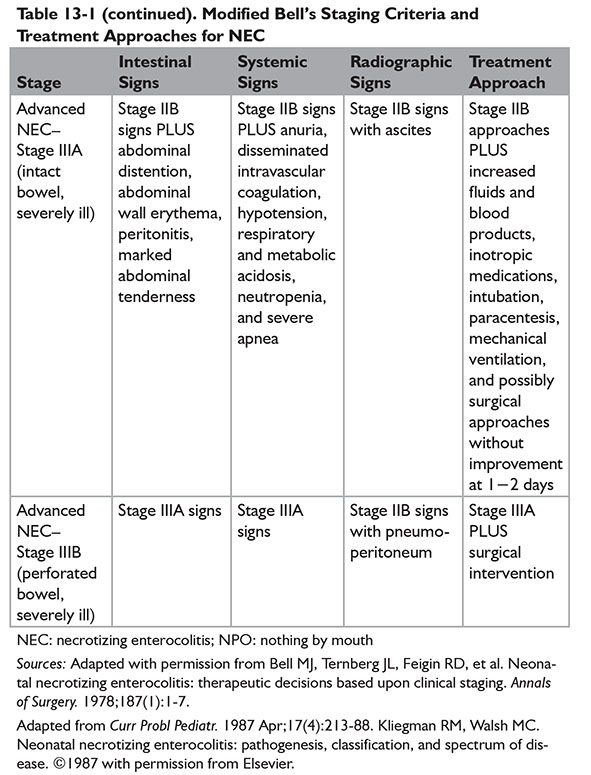

NEC has a spectrum of presentation. One of the first staging criteria was developed by Bell et al.8 Staging gives a starting point for treatment approaches.

Bell Stage I—Suspected NEC

Bell Stage I—Suspected NEC

Characteristics include history of stress; GI signs such as abdominal distention (mild), bloody stools, emesis (bilious or bloody), increasing pre-feeding residuals, and poor toleration of feedings; and systemic indicators such as apnea, bradycardia, lethargy, and temperature instability. Abdominal radiography illustrates abdominal distention with mild ileus.

Bell Stage II—Definite NEC

Bell Stage II—Definite NEC

Characteristics include Stage I features with the following differences: gross or persistent GI bleeding and significant abdominal distention. Abdominal radiography shows significant abdominal distention with ileus, small bowel edema, pneumatosis intestinalis (intestinal intraluminal gas), portal venous gas, or unchanging rigid or fixed loops of bowel.

Bell Stage III—Advanced NEC

Bell Stage III—Advanced NEC

Characteristics include features of Stage I and Stage II with the following differences: worsening of vital signs, septic shock, and GI bleeding. Abdominal radiography illustrates pneumoperitoneum in addition to Stage II findings.8

A modified Bell staging approach was described by Kliegman and Walsh, incorporating subcategories and therapeutic options for each subcategory (Table 13-1).9

The most common parts of the GI system affected—in order of decreasing frequency—are the terminal ileum, right colon, colon (transverse and descending), appendix, jejunum, stomach, duodenum, and esophagus.2 Peritonitis may also be present. Abdominal signs of peritonitis include discoloration, edema, induration, and resistance to palpation.10 Neonates may also experience leukopenia, leukocytosis, bandemia, thrombocytopenia, metabolic acidosis, or hyperglycemia.2,3

Diagnosis

Diagnostic characteristics are abdominal distention or tenderness, bloody stools, evidence of intolerance to feedings by emesis or pre-feeding residuals, and abdominal radiographic findings (e.g., pneumatosis intestinalis).3 Other characteristics are components of the Bell staging criteria and physical examination. Presence of pneumatosis intestinalis confirms diagnosis of NEC.

Medical Treatment

The first step in medical management is to stop enteral intake, while initiating bowel rest and GI decompression, and start empiric parenteral antibiotics preventing bacterial invasion and translocation. Parenteral nutrition (PN) support may also be initiated. An infectious workup should be performed including microbiologic evaluation of blood, cerebral spinal fluid, and urine.11 Specific approaches for PN support are not discussed. (For information on PN, see Chapter 3.)

Empiric Antibiotics

Parenteral empiric antibiotics should be initiated when NEC is suspected and then continued with diagnosis. The antibiotic regimen should cover gram-negative, gram-positive, and possibly anaerobic bacteria. Empiric regimens may include an aminoglycoside or third-generation cephalosporin for gram-negative bacteria coverage, ampicillin or vancomycin for gram- positive coverage, and possibly clindamycin or metronidazole for anaerobic coverage.11 Empiric antibiotic regimens should be de-escalated after a pathogen is identified and susceptibilities are available. Serum concentration monitoring is recommended for aminoglycoside- and vancomycin-containing regimens if continued beyond 48 to 72 hours. Renal function monitoring, which includes laboratory assessment and urine output assessment, is also recommended.

Anaerobic Antibiotic Treatment

Anaerobic antibiotic use is defined as administration of an antimicrobial medication with anaerobic spectrum coverage in vitro against intestinal anaerobic bacilli on day 1 of NEC treatment. Medications with anaerobic coverage include amoxicillin−sulbactam, ampicillin−sulbactam, cefoxitin, clindamycin, metronidazole, moxifloxacin, piperacillin−tazobactam, or any carbapenem. Very low birth weight (VLBW) (≤1.5 kg) neonates were assessed for a composite end point of death during hospital admission and intestinal strictures as well as the end points individually by comparing to matched neonates who did not receive anaerobic coverage for NEC treatment. Patients were stratified to either medical

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree