Necrosectomy for Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Thomas J. Howard

Introduction

The intensity and complexity of clinical care and decision making in patients with the diagnosis of acute necrotizing pancreatitis (ANP) is one of the most challenging tasks that the general surgeon faces. These patients require a rapid and precise diagnosis, aggressive fluid resuscitation, organ support, and optimized nutritional supplementation. Accurate interpretation of radiographic imaging is essential to quantify the volume and location of both pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis, as well as gauge the severity of illness utilizing the computed tomography severity index (CTSI). After hospital admission, frequent clinical reassessments of the patient are essential to ensure treatment goals are met, investigate physiologic derangements (temperature spikes, mental status changes, organ dysfunction, and laboratory abnormalities), and direct therapeutic decision making. Disease-specific outcomes for patients with ANP are optimum in centers with a large clinical experience treating patients with this disease where a tightly bound team of physicians, nurses, operating room personnel, dieticians, and other health care specialists are involved in their care. This chapter is focused on the clinical course, indications for interventions, and the various techniques for necrosectomy, and postoperative complications in patients with ANP.

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a relatively common disease affecting approximately 79.8/100,000 hospitalized patients per year in the United States (approximately 240,000 patients/year) with the majority of cases attributable to either alcohol (40%) or gallstones (35%). It occurs in two forms, with 80% of patients having acute edematous pancreatitis, a disease which is generally mild, self-limiting, and resolves in 5 to 7 days with intravenous fluid hydration, limiting oral intake, and generalized supportive care. In 20% of patients, the disease is manifest as ANP, a severe physiologic and metabolic derangement, which is associated with multiple organ system dysfunction and local complications such as hemorrhage, abscess, and pseudocyst formation. While the mortality rate from acute edematous pancreatitis is less than 1%, the overall mortality rate for ANP is in the range of 10% to 20%. Despite considerable research, it remains unclear why after the inciting molecular events (intra-acinar activation of trypsinogen) that trigger acute pancreatitis occur; some patients develop only interstitial or edematous pancreatitis while others progress to a more severe form of the disease manifest by pancreatic necrosis. Because of this clinical uncertainty, establishing an accurate diagnosis coupled with staging the disease severity early following admission is essential to stratify patients and triage them to appropriate levels of care.

The diagnosis of AP is established by a thorough history and physical examination combined with appropriate laboratory testing and radiographic imaging. In a patient with typical symptoms of severe epigastric abdominal pain radiating to the back, nausea, vomiting, a low-grade fever, and leukocytosis, an elevated amylase and/or lipase levels are the backbone of laboratory diagnosis. Because of a longer half-life and greater specificity, a serum lipase level of greater than three times the upper limit of normal is the most sensitive and specific serum test. Imaging studies, particularly contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT), is quite helpful for making the diagnosis in equivocal cases. The severity of an episode of AP can be prognosticated using clinical and laboratory data points plugged into any one of multiple established scoring systems (Ranson’s, Glasgow, APACHE II), or a radiographic imaging scoring system (Table 1). Both the Ranson’s and Glasgow scoring systems require 48 hours of data to be accurately calculated and both are limited to predicting severity at only one point in time along the disease course. In both systems, a score of 3 or higher is indicative of severe disease. By contrast, the APACHE II scoring system can be recalculated daily (mild pancreatitis = score ≤ 7) providing prognostic information over the entire clinical course of disease. Practically, the large number of clinical variables required for calculation limits its clinical utility. In terms of single serum markers to measure ANP, measurement of C-reactive protein (CRP), an inflammatory mediator, at a level greater than 150 mg/mL on the second day of symptoms, has been strongly correlated with the presence of pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis. The CTSI as defined by Balthazar is a scoring system that provides points for both the CT grade and percent necrosis, which provides three broad categories of scores (0–3, 4–6, 7–10) that have been shown to correlate well with the incidence of death and the development of local complications.

Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Once the diagnosis of ANP is established, efforts to mediate and blunt the clinical disease course are implemented. Conceptually, it is helpful to view the pathophysiology of ANP as evolving in two clinical phases: an early (<7 days from the onset of pancreatitis) cytokine-mediated vasoactive phase where deaths are related to progressive organ dysfunction and hypoperfusion; and a later (>14 days from the onset of pancreatitis) infection-mediated septic phase, commonly attributed to secondary bacterial infection (e.g., infected pancreatic necrosis) leading to persistent multiple organ system failure.

Table 1 Prognostic Scoring Systems in Acute Pancreatitis and their Criteria for Differentiating Mild from Severe Disease | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Efforts to prevent early deaths have been targeted at controlling the mediators of the pancreatic inflammatory response and adequate early fluid resuscitation. Unfortunately, to date, randomized clinical trials

using inhibitors of pancreatic secretion, serum proteases, and platelet-activating factor have all failed to demonstrate a benefit in patients with AP. Adequate, early (within 24 h of diagnosis) fluid resuscitation may influence the clinical course of patients with AP by reducing the systemic inflammatory response and development of organ failure. Successful targeted treatments to modulate the inflammatory response early in the clinical course of AP are of considerable interest and may be successful; however, further investigation is necessary before their routine implementation.

using inhibitors of pancreatic secretion, serum proteases, and platelet-activating factor have all failed to demonstrate a benefit in patients with AP. Adequate, early (within 24 h of diagnosis) fluid resuscitation may influence the clinical course of patients with AP by reducing the systemic inflammatory response and development of organ failure. Successful targeted treatments to modulate the inflammatory response early in the clinical course of AP are of considerable interest and may be successful; however, further investigation is necessary before their routine implementation.

Prevention of mortality in the late, infection-mediated septic phase of ANP is realized by improved supportive care (enteral nutrition, prophylactic antibiotics), avoiding unnecessary or ill-timed surgical intervention (CT-guided fine-needle aspiration [FNA], delayed operative intervention), and targeted, minimally invasive necrosectomy for infected necrosis using a step-up approach.

Nutritional Support

The concept that limitation of enteral feeding is necessary in ANP to avoid further stimulation of pancreatic exocrine secretion is outdated. Recent evidence from several randomized clinical trials have shown that enteral nutrition, when tolerated, is cost effective, decreases catheter-related infectious complications, and improves blood glucose control. Theoretical advantages of enteral nutrition that improves intestinal mucosal integrity and preserves barrier function leading to a moderation of the patient’s systemic inflammatory response remain unproven. Unfortunately, not all patients tolerate enteral feeding, particularly early in the course of their disease. In these situations, total parenteral nutrition providing adequate calories and protein remains useful.

Prophylactic Antibiotics

Secondary infection in pancreatic necrosis is thought to occur through translocation of intestinal bacteria (aerobic gram-negative rods, Enterococcus, and anaerobes) or through seeding caused by transient bacteremias related to invasive arterial monitoring lines and venous access sites (gram-positive cocci). These infections are polymicrobial in approximately 30% of patients and occasionally contain resistant organisms (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA], vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus [VRE]) or fungus. The incidence of infection in pancreatic necrosis is thought to increase over time and has been associated with mortality. Efforts to prevent secondary pancreatic infections have involved attempts to maintain gut mucosal barrier function through enteral nutrition, provision of probiotics, or treatment with prophylactic antibiotics. Although several early studies and a subsequent meta-analysis on the use of prophylactic antibiotics suggested a reduction in the incidence of pancreatic infections, recent large, well-designed controlled clinical trials have failed to demonstrate either a reduction in pancreatic infection or mortality rates with their use. While some controversy remains regarding the use of prophylactic antibiotic in ANP, our current policy is to give antibiotic “on demand” to cover possible sources of infection for specific clinical indications in critically ill patients until culture results are available to guide further therapy.

Timing of Surgical Intervention

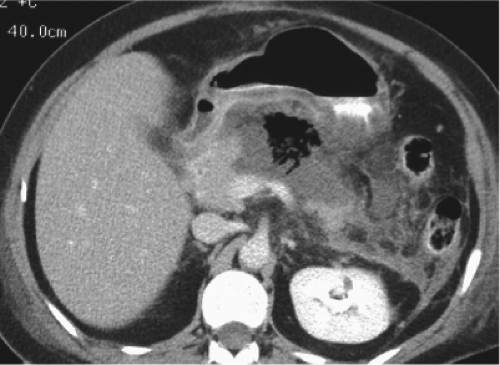

Once the presence of infected pancreatic necrosis is established, there is a general consensus that intervention, either necrosectomy or percutaneous drainage, has the capacity to reverse organ dysfunction and improve patient outcome. The presence of infection in pancreatic necrosis is confirmed by either: (1) radiographic evidence of extra-luminal gas located in the area of necrosis as seen on cross-sectional imaging (Fig. 1), or (2) CT-guided percutaneous FNA showing organisms on gram stain or culture. Percutaneous FNA has a reported sensitivity and specificity of greater than 95%, which allows for the accurate discrimination between infected and sterile necrosis in patients with ANP. While infection in pancreatic necrosis is an indication for intervention, there remains significant controversy over the role of necrosectomy in patients with sterile necrosis. In terms of timing, operative necrosectomy is best utilized after the third week of a patient’s clinical course to allow time for the resolution of early cytokine-mediated vasoactive disease phase, as well as the structural demarcation between live and dead tissue in the retroperitoneum. In patients with infected pancreatic necrosis diagnosed early in their clinical course (<3 weeks), percutaneous CT-guided catheter drainage (PCD) can be an extremely effective treatment modality. Not only can it be effective in up to one-third of patients with infected pancreatic necrosis when utilized as the sole treatment modality, but even in those patients who ultimately require operative necrosectomy, control of sepsis, and buying time to optimize the patients clinical status prior to operation can be helpful.

Methods of Necrosectomy

Accurate cross-sectional imaging with CECT to quantitate the extent of pancreatic parenchymal and peripancreatic necrosis, document diffuse or walled-off necrosis, and identify a disconnected left pancreatic remnant are critical to choose the most appropriate method of necrosectomy. Walled-off pancreatic necrosis is an increasingly well-recognized entity in which encapsulation of the necrotic process within the lesser sac bound by the stomach, duodenum, transverse mesocolon, and omentum creates a localized mature collection analogous to a pancreatic pseudocyst (Fig. 2). The benefit of this anatomic configuration of pancreatic necrosis is that all minimally

invasive necrosectomy techniques, endoscopic transgastric, video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD), or PCD is applicable. By contrast, extension of the necrosis down the pericolic gutters (particularly right side) or into the root of the mesentery makes it much less amenable to minimally invasive approaches and may best be approached with an open necrosectomy. In patients with evidence of an isolated left pancreatic remnant, a transgastric approach, either endoscopic or open, may prevent the development of a postoperative pancreatic fistula.

invasive necrosectomy techniques, endoscopic transgastric, video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD), or PCD is applicable. By contrast, extension of the necrosis down the pericolic gutters (particularly right side) or into the root of the mesentery makes it much less amenable to minimally invasive approaches and may best be approached with an open necrosectomy. In patients with evidence of an isolated left pancreatic remnant, a transgastric approach, either endoscopic or open, may prevent the development of a postoperative pancreatic fistula.

Over the last decade, the development of minimally invasive techniques to treat gastrointestinal disorders has soared as endoscopic and percutaneous technology and equipment have been developed (Table 2). Limitations to applying these technologies in patients with pancreatic necrosis are: the small numbers of patients in any single center, differences in regional expertise, and substantial technical variations within techniques. Overcoming these obstacles has been challenging but two recent prospective multi-institutional studies deserve mention. The PANTER study (pancreatitis, necrosectomy vs. step-up approach), is however, one of the few randomized multi-institutional clinical trials in this area. Patients with suspected or confirmed infected necrosis were randomly assigned to either open necrosectomy or a step-up approach to treatment. The step-up approach consisted of percutaneous drainage followed, if necessary, by minimally invasive retroperitoneal necrosectomy. Primary end points were a composite of major complications (new-onset multiple-organ failure or multiple systemic complications, perforation or a visceral organ, enterocutaneous fistula, or bleeding) or death. The investigators found that 35% of patients were treated successfully with percutaneous catheter drainage alone while the remainder required percutaneous drainage followed by minimally invasive retroperitoneal necrosectomy. Compared to open necrosectomy, the step-up approach significantly decreased the rate of new onset multiple organ failure (12% vs. 40%), incisional hernias (7% vs. 24%), and new onset diabetes (16% vs. 38%) but did not significantly affect mortality. These reductions in the rate of composite end points show that a step-up approach utilizing minimally invasive techniques has advantages over open necrosectomy in patients with infected pancreatic necrosis. In another multicenter, prospective, single-arm phase II study, VARD was used in 24 patients with a 30-day in-hospital mortality of 2.5%, bleeding complication rate of 7.5%, and an enteric fistula rate of 7.5%. Similar to the results of the PANTER study, in this cohort, nine patient (23%) required percutaneous catheter drainage only for resolution of their infected pancreatic necrosis without the need for subsequent VARD. These two multicenter randomized clinical trials have set the stage for an evidence-based approach to the optimal treatment of patients with pancreatic necrosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree