34 Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are commonly (but not universally) associated symptoms. The word nausea is derived from the Greek nautia, meaning sea-sickness, while vomiting is derived from the Latin vomere, meaning to discharge. Nausea is a subjective sensation whereas vomiting is the reflex physical act of expulsion of gastric contents. Retching is defined as ‘spasmodic respiratory movements’ against a closed glottis with contractions of the abdominal musculature without expulsion of any gastric contents, that is, ‘dry heaves’ (American Gastroenterological Association, 2001). It is important to differentiate vomiting from regurgitation, rumination and bulimia. Regurgitation is the return of oesophageal or gastric contents into the hypopharynx with little effort. Rumination is the passive regurgitation of recently ingested food into the mouth followed by re-chewing, re-swallowing or spitting out. It is not preceded by nausea and does not include the various physical phenomena associated with vomiting. Bulimia involves overeating followed by self-induced vomiting.

Epidemiology

Nausea and vomiting from all causes have significant associated social and economic costs in terms of loss of productivity and extra medical care. In the community, nausea (with or without vomiting) is most likely to be associated with infection, particularly gastro-intestinal infection. Vestibular disorders may cause vomiting as can motion sickness. Nausea and vomiting may be associated with pain, for example, migraine and severe cardiac pain. Many medicines also cause nausea and occasionally vomiting as a common dose-related (Type A) adverse effect. This is particularly common with opioid use in palliative care. Nausea and vomiting also occur post-operatively or in association with cytotoxic chemotherapy, or radiotherapy. These and other causes of nausea and vomiting are listed in Table 34.1.

Table 34.1 Selected causes of nausea and vomiting

| Central | |

|---|---|

| i. Intracranial | Migraine |

| Raised intracranial pressure (tumour, infection, haemorrhage, hydocephalus, etc.) | |

| ii. Labyrinthine Iatrogenic | Labyrinthitis, motion sickness, Ménière’s disease, otitis media |

| Cancer chemotherapy | |

| Many other medicines (e.g. opioids) | |

| Radiotherapy | |

| Post-operative | |

| Endocrine/ metabolic | Pregnancy, uraemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, Addison’s disease, acute intermittent porpyhria |

| Infectious | Gastroenteritis (viral or bacterial) |

| Other infections elsewhere | |

| Gastro-intestinal disorders | Mechanical obstruction (gastric outlet or small bowel) |

| Organic gastro-intestinal disorders (e.g. cholecystitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, etc.) | |

| Functional gastro-intestinal disorders (e.g. non-ulcer dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome, etc.) | |

| Psychogenic disorders | Psychogenic vomiting, anxiety, depression |

| Pain related | Myocardial infarction |

(adapted from Quigley et al., 2001)

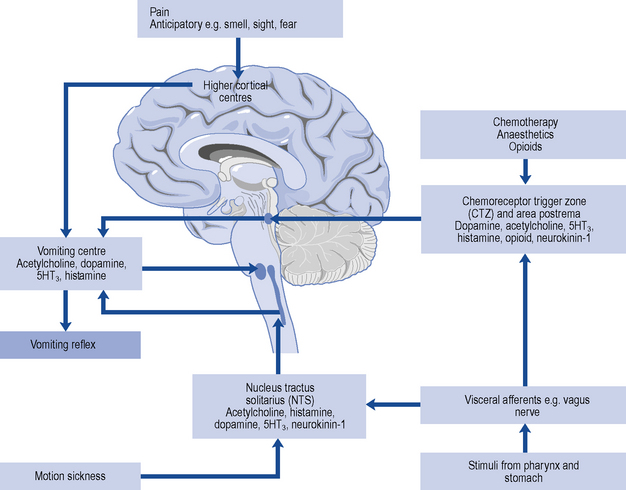

Pathophysiology

The vomiting centre is situated in the dorsolateral reticular formation close to the respiratory centre and receives impulses from higher centres, visceral efferents, the eighth (auditory) nerve (the latter two through the nucleus tractus solitarius) and from the CTZ (Fig. 34.1). It includes a number of brainstem nuclei required to integrate the responses of the gastro-intestinal tract, pharyngeal muscles, respiratory muscles and somatic muscles to result in a vomiting episode. The vomiting centre may be stimulated in association with, or in isolation from, the nausea process.

Patient management

Management of the patient with nausea and vomiting is approached in three steps.

Some scenarios illustrating common therapeutic problems in the management of nausea and vomiting are outlined in Table 34.2.

Table 34.2 Common therapeutic problems in managing patients with nausea and vomiting

| Problem | Possible cause/solution |

|---|---|

| Persistent nausea and vomiting despite treatment | Is the cause correctly diagnosed? |

| Review the antiemetic agent and the dose: if both correct, change to or add a second agent | |

| Patient with PONV is vomiting despite suitable antiemetic regimen | Check analgesia: pain may be causing nausea and vomiting, or patient-controlled analgesia may require adjustment downwards to reduce analgesic dose |

| Patient with bowel obstruction is passing flatus | Prokinetic drug is first-choice antiemetic. 5HT3 antagonists may also be effective |

| Patient with bowel obstruction is not passing flatus | Spasmolytic drug is first choice. Prokinetic drugs are contraindicated. Similarly, bulk-forming, osmotic and stimulant laxatives are inappropriate; phosphate enemas and faecal softeners are better |

| A terminally ill patient receiving diamorphine is vomiting, despite use of haloperidol | Levomepromazine given as a 24-h subcutaneous infusion can be very effective |

| A patient with renal failure (uraemia) is vomiting | Consider a 5HT3 antagonist |

| A patient develops an acute dystonic reaction to metoclopramide | Give an intramuscular injection of an antihistamine. Such extrapyramidal reactions to metoclopramide are more common in young adults (especially females) and this agent is best avoided in this group |

PONV, post-operative nausea and vomiting.