Mycotic Aneurysms

Carlos H. Timaran

Mycotic aneurysms are complex conditions of peripheral vascular disease that are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Only a timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment can result in improved outcomes. Unfortunately, their management is complex and challenging. This chapter reviews the pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of mycotic aneurysms in the hope of aiding surgeons to optimize the management of these conditions. Various treatment options are discussed, ranging from antibiotic therapy alone to resection of the infected aneurysm with in situ or remote arterial reconstruction. The use of novel endovascular therapies, either as a definitive treatment or as a bridge to open repair, are also covered. Because most mycotic aneurysms are aortic and only few cases of isolated or coexistent peripheral aneurysms have been reported, the principles of management of both conditions, which are similar, are discussed concurrently.

Pathogenesis

Although the term mycotic aneurysm was initially introduced by Osler to denote infected aneurysms associated with endocarditis, it is currently broadly used to describe any infected aneurysm, regardless of etiology. Either hematogenous seeding of the arterial wall during episodes of bacteremia or contiguous spread of local infections may result in primary arterial infections. Because an intact endothelium provides a relative barrier to infection, endothelial or intimal injury related to atherosclerosis is usually required prior to the development of the arterial infection. Alternatively, preexisting aortic aneurysms may become secondarily infected by hematogenous seeding due to infection of the atherosclerotic arterial wall or sac thrombus.

Prior to the introduction of antibiotics, the causative organisms were primarily those associated with endocarditis, that is, streptococcal species, staphylococcal species, and pneumococcus. Currently, Gram-positive cocci are responsible for 50% of the cases (staphylococcus in 30% and streptococcus in 20%) and Gram-negative bacilli are usually cultured in 35% (salmonella in 20% and E. coli in 15%).

The clinical presentation of the patients with mycotic aortic aneurysms ranges from asymptomatic status with positive findings on radiologic imaging studies to overt aortic rupture and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Approximately, half of the patients have a history of a recent or ongoing systemic infection. Comorbid conditions associated with relative immunosuppression are common and more than two-thirds of the patients may have a history of diabetes, chronic renal failure, chronic steroid use, or chronic illnesses. Systemic symptoms are usually present in >90% of the patients and include fever, chills, and sweats. Abdominal or back pain may be present in two-thirds of the patients. Hemodynamic instability is usually present in a minority of patients, despite aortic rupture may be present in up to one-quarter of the cases. Laboratory abnormalities typically denote systemic inflammation with elevated sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein and leukocytosis. More than two-thirds of the patients with mycotic aneurysms of the aorta meet the clinical criteria for SIRS at initial presentation.

Diagnosis

Imaging studies are certainly the method to establish the presence of an aneurysm. The specific diagnosis of a mycotic aneurysm is, however, challenging and no imaging study is accurate enough to determine the infectious nature of an aneurysm in all cases. Computed tomography (CT) angiography is the mainstay of radiologic diagnosis of a mycotic aneurysm. The entire aorta should be imaged since mycotic aneurysms are found throughout the aorta: ascending aorta (6%), descending thoracic aorta (23%), paravisceral aorta (6%), juxtarenal aorta (10%), and infrarenal aorta (32%). A key feature in the diagnosis of mycotic aneurysms is the aneurysm morphology. Mycotic aneurysms are characteristically saccular in >90% of the cases. Many of these aneurysms can present as perforated ulcers that expand rapidly and may frequently progress to contained ruptured aneurysms. Secondary signs of infection on CT scan include the presence of a para-aortic soft tissue mass, stranding, or fluid, which are seen in nearly half of the cases (Fig. 1). Thirty percent of patients have CT evidence of aortic rupture. Retroperitoneal gas in the context of a saccular aneurysm is rare (7% of the cases), but pathognomonic for a mycotic aneurysm. Vertebral body destruction with psoas abscess adjacent to an aortic aneurysm is another ominous finding on CT scan. Among patients with serial CT scans available for comparison, peri-aortic edema and interval development or expansion of an aneurysm are highly suspicious for the presence of an infected aneurysm.

Arteriography may demonstrate the presence of a saccular aneurysm with lobulated contour. The various secondary signs of a mycotic aneurysm, as discussed earlier, will not be visualized on arteriography as only the luminal contour of the vessel may be imaged. Arteriography is, therefore, used to determine specific anatomic features preoperatively or prior to endovascular repair. Nuclear imaging often reveals inflammatory activity in the vicinity of the aneurysm, consistent with an infection. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show a

saccular aneurysm. Since most cases may be diagnosed by clinical presentation and CT angiography, other imaging studies such as MRI, standard arteriography, and nuclear imaging should be reserved for stable patients in whom the diagnosis remains uncertain (Fig. 2).

saccular aneurysm. Since most cases may be diagnosed by clinical presentation and CT angiography, other imaging studies such as MRI, standard arteriography, and nuclear imaging should be reserved for stable patients in whom the diagnosis remains uncertain (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Retroperitoneal gas adjacent to a saccular aneurysm on computed tomography is rare (7% of cases), but pathognomonic for a mycotic aneurysm. |

Fig. 2. CT angiography usually demonstrates the presence of a saccular aneurysm with lobulated contour. |

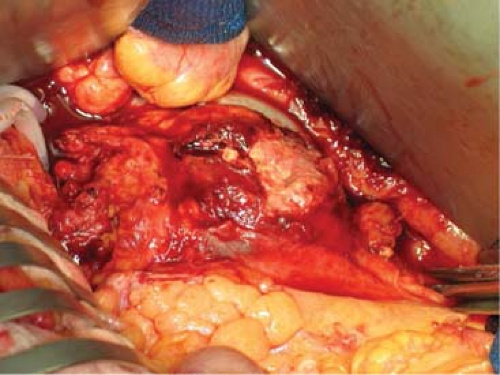

Fig. 3. Proximal and distal aortic control should be obtained well away from the inflamed segment of aorta prior to debridement. |