Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Lymphadenitis

Definition

Lymphadenitis caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Synonym

Tuberculous lymphadenitis.

Epidemiology

Tuberculosis was for centuries one of the most severe human diseases and, although its incidence has steadily decreased in more advanced countries, it remains a major health problem in developing nations. Among infectious diseases, tuberculosis is still the leading cause of death (1). About a third of the world’s population harbors M. tuberculosis and is at risk for development of the disease (1,2). The World Health Organization predicted the continuous increase of tuberculosis and estimated 12 million new cases and 3 million deaths annually (3,4). In the United States, tuberculosis had been decreasing annually by an average of 5%, remaining confined largely to elderly, institutionalized, and foreign-born persons. However, in the 1980s, the declining trend was reversed, and annual increases in the incidence of tuberculosis were again being registered (1,5,6,7,8). The strong resurgence of tuberculosis has been caused by the epidemics of drug abuse and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection spread by travel and immigration. In one New York City inner-city hospital, the total number of new mycobacterial isolates increased 10-fold from 1982 to 1986. Of these patients, 80% were intravenous drug abusers, and their tuberculosis presented early and aggressively (2). Strong reciprocal interactions occur between HIV and M. tuberculosis infections, resulting in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and in disease that is hard to control. Tuberculosis kills one in every seven people with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and one-third of the increase in worldwide tuberculosis cases is due to the HIV epidemic (9). Presently, the tuberculosis epidemic in the United States is controlled, and the incidence of the infection is again decreasing (10). In a recent study of 106 patients, tuberculous lymphadenitis occurred predominantly in young, foreign-born women, a mean 5 years after arrival in the United States. Lymphadenopathies were cervical in 57% and supraclavicular in 26%, whereas 38% had abnormal chest radiographs. Granulomas were seen in 61% of fine needle aspirates and 88% of biopsies (11). In contrast, in Asia and Africa, the rates of tuberculosis are increasing rapidly; in some of these areas up to 50% of the HIV-infected population is coinfected with M. tuberculosis (3).

Etiology

Mycobacterium tuberculosis var hominis and var bovis is the agent of tuberculosis in humans and other animal species. The organisms are slightly curved, slender rods that are 2 to 4 μm long. Also known as tubercle bacilli, they appear in stained tissues uniformly or more often beaded and can be cultured on specific media, although they may take long time to develop (12). The walls of mycobacteria have a lipid content of up to 60% attached to polysaccharides. Because of the high lipid content of their outer walls, mycobacteria are hydrophobic, impermeable to stains, acid-fast, and resistant to bactericidal substances, antibodies, and complement (12). Ziehl-Neelsen, Kinyoun, and Fite-Faraco are specific histologic stains based on the acid-fast property of mycobacteria.

Pathogenesis

The broad range of lesions that can be observed in tuberculosis is the result of a continuous interaction between bacterial virulence and individual response. The latter varies from hypersensitivity, expressed by exudative, generally nonspecific lesions, to immunity, expressed by proliferative, granulomatous, specific lesions. Primary tuberculosis develops when M. tuberculosis var hominis is inhaled into the lungs or, far less frequently, when M. tuberculosis var bovis is ingested and infects the intestines.

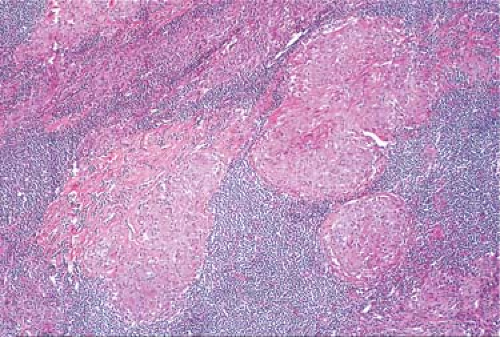

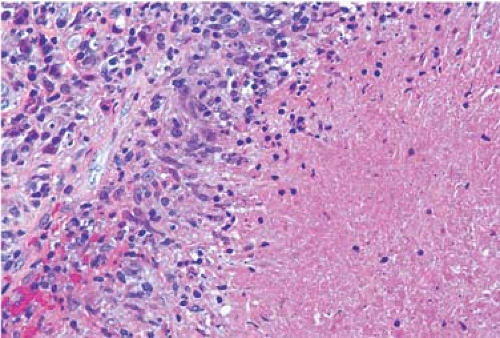

The primary phase of pulmonary tuberculosis begins with inhalation of bacilli and is followed by a T-cell–mediated immune response that induces hypersensitivity to the organism and controls the infection (13). The lymph nodes are involved in primary tuberculosis as tubercle bacilli engulfed by phagocytes are transported from the initial focus of infection through the lymphatics to the tributary lymph nodes. Because the primary focus is usually in the lungs, most commonly subjacent to the pleurae of the upper lobes, the bronchopulmonary lymph nodes become involved, forming together the classic Ghon complex. With the rare primary lesions that occur in intestine, tonsil, eye, ear, or skin, regional lymph nodes may be similarly involved. Secondary tuberculosis arises in a previously sensitized person by reactivation of a primary complex (usually the lymph nodes, in which tubercle bacilli may survive for long periods of time) or by new exogenous infection. The new lesions may remain restricted to the lungs, disseminate widely in the form of miliary tuberculosis, or localize in a variety of organs with further local chronic progression. In any of these cases, the regional draining lymph nodes are affected, and chronic proliferative tuberculous lymphadenitis results. In unimmunized organisms, the tissue reaction to tubercle bacilli is essentially exudative, necrotizing, and nonspecific (Fig. 22.1). As specific immunity develops, the lesions become localized, proliferative, and specific, reflected by the characteristic tuberculous granuloma (Fig. 22.2). In most cases, cell-mediated specific immunity to M. tuberculosis develops within 2 to 6 weeks after infection. Most bacilli are killed by macrophages, and a few persist in a dormant but viable state. The only signs of the primary infection are a small, healed, calcified lesion in the lung and skin test reactivity to a purified protein derivative (PPD) of tuberculin (11). In persons with immune deficiency, whether congenital or acquired (e.g., organ transplant recipients, HIV-infected persons), the course of tuberculosis is entirely different (1,14). As cellular immunity is gradually destroyed, old, latent tuberculous lesions are reactivated, PPD reactivity is compromised, and the progress of disease is accelerated. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis, such as miliary tuberculosis, lymphadenitis, and various visceral localizations, is more common (14,15,16).

Figure 22.1. Pulmonary hilar lymph node with large area of caseous necrosis, devoid of granulomas. Hematoxylin, phloxine, and saffron stain. |

Clinical Syndrome

Lymph node tuberculosis is still an important issue in developed countries and must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Even in adult HIV-negative patients, extrathoracic tuberculous lymphadenitis is common and occurs more frequently in women and immigrants from India and Southeast A frica (17). The most common form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis is tuberculous lymphadenitis (18,19). In one study of 60 patients from Germany, cervical lymph nodes were most frequently involved (63.3%), followed by the mediastinal (26.7%) and the axillary lymph nodes (8.3%) (20). The distribution of tuberculosis in 100 cervical lymph nodes was found to be commonest in the posterior triangle (51%), followed by upper deep cervical (48%) and submandibular (36%). The least frequent were submandibular (3%), submental (4%), and lower deep cervical (9%). Unilateral node involvement was 83%; bilateral, 17%. These results indicate that unilateral, painless, enlarged, and matted cervical lymph nodes in one of these areas are more likely to be of tubercular design (21). In a study of 138 patients, the lymph nodes were matted in 26.8%, and fluctuation was present in 12.3% (18). In HIV-infected patients, abdominal lymph node involvement was reported to be more frequent, usually in addition to peripheral lymphadenopathy (22). Mycobacterial lymphadenitis developing after the initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy is more likely to be localized and focal and caused by unsuspected M. avium MAI lymphadenitis (23).

The gross features of tuberculosis are usually sufficiently distinctive that a tentative diagnosis can be made and precautions taken for avoiding infection (24). On section, the caseous necrotic areas appear as creamy white patches, becoming chalky with the deposition of calcium. The periphery is densely fibrosed (Fig. 22.3). In time, some nodes may be entirely converted into radio-opaque, rock-hard masses (24). The tuberculous lymph nodes are matted, and large areas may be entirely necrotic. The tracheobronchial lymph nodes commonly involved in the tuberculous primary complex may reach large proportions, particularly in children. They may spread to adjacent structures, causing abscesses or traction diverticula

(25), or adhere to blood vessels. Subsequent invasion of a blood vessel results in miliary dissemination.

(25), or adhere to blood vessels. Subsequent invasion of a blood vessel results in miliary dissemination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree