15 Musculoskeletal disorders

Disorders of the musculoskeletal (MSK) system are extremely common, accounting for up to a quarter of new consultations in general practice. They are the single most frequent cause of physical disability in the elderly. The principal manifestations are pain and impairment of locomotor function. Non-inflammatory conditions are far more prevalent than inflammatory disease. Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disorder, with knee involvement a major cause of disability. Osteoporosis is the most prevalent bone disorder, with 1 in 3 women sustaining an osteoporotic fracture at some point during their lifetime.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS

JOINT PAIN

ACUTE MONOARTHRITIS

Causes of acute inflammation in a single joint are listed in Box 15.1. The site affected rarely helps to identify the cause except in the case of gout, which typically affects the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

15.1 CAUSES OF ACUTE MONOARTHRITIS ![]()

Joint aspiration is normally required to exclude sepsis and to look for crystals.

OLIGOARTHRITIS

Oligoarthritis is arthritis affecting two, three or four joints. By far the most common cause is osteoarthritis (OA), which is a non-inflammatory condition characterised by degenerative joint change. Inflammatory oligoarthritis mainly targets lower limb joints and is usually asymmetrical; it is a common presentation of seronegative spondarthritis (e.g. reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, enteropathic arthritis). Sequential joint involvement ascending a limb suggests sepsis.

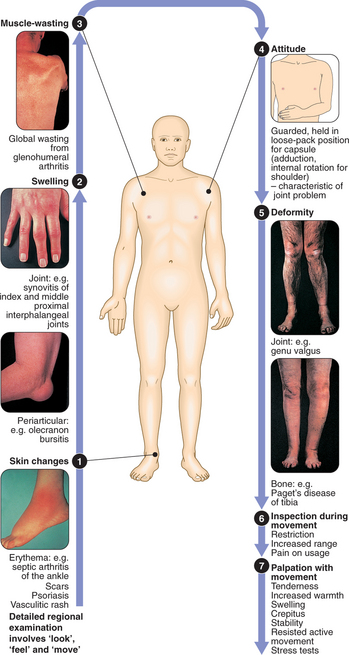

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

POLYARTHRITIS

Polyarthritis is inflammation affecting five or more joints. The symmetry and pattern of involved joints are important in determining the cause (Box 15.2). Accompanying periarticular or extra-articular features may aid diagnosis.

| Cause | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Non-inflammatory | |

| Generalised osteoarthritis | Small and large joints, only a few joints symptomatic at any one time |

| Inflammatory | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Symmetrical, small and large joints, upper and lower limbs |

| Seronegative spondarthritis (psoriasis, reactive, ankylosing spondylitis, enteropathic arthropathy) | Asymmetrical, large > small joints, lower > upper limbs, spondylitis |

| Lupus | Symmetrical, small > large joints, joint damage uncommon |

| Chronic gout | Distal > proximal joints preceded by acute attacks |

| Viral arthritis | Very acute, self-limiting (<6 wks) |

| Chronic sarcoidosis | Symmetrical, small and large joints |

REGIONAL PERIARTICULAR PAIN

SINGLE REGIONAL PAIN

Elbow pain

Lateral epicondylitis (‘tennis elbow’): The most common periarticular lesion (Box 15.3).

15.3 PERIARTICULAR LESIONS PRESENTING AS ELBOW PAIN ![]()

| Lesion | Pain | Examination findings, tests |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Tennis elbow’ | ||

| ‘Golfer’s elbow’ | ||

| Olecranon bursitis | Olecranon | Fluctuant tender swelling over olecranon |

Lower limb pain

Causes of periarticular pain affecting the lower limb are listed in Box 15.4.

15.4 PERIARTICULAR LESIONS IN THE LOWER LIMB ![]()

| Lesion | Pain | Examination findings, tests |

|---|---|---|

| Trochanteric bursitis | Upper lateral thigh, worse on lying on that side at night | Tender over greater trochanter |

| Pre-patellar bursitis | Anterior patella | Tender fluctuant swelling in front of patella |

| Popliteal cyst (‘Baker’s cyst’) | Popliteal fossa | Tender swelling of popliteal fossa, usually reducible by massage with knee in mid-flexion |

| Plantar fasciitis | Under heel, worse on standing and walking | Tender under distal calcaneus/plantar fascia insertion site |

| Achilles tendinitis | Localised to tendon |

BACK AND NECK PAIN

LOW BACK PAIN

Clinical assessment

Radicular (nerve root) pain: This is commonly caused by a prolapsed intervertebral disc in young adults, most commonly at L4 or L5. Patients experience severe, sharp pain radiating down the back of the leg beyond the knee (‘sciatica’). The unilateral leg pain is worse than the low back pain, and is aggravated by coughing and straining. Straight leg raising reproduces the pain, and examination may reveal motor weakness and/or sensory loss limited to one nerve root with loss of the corresponding reflex. Around 50% of patients recover by 6 wks with conservative management only. Compression of multiple nerve roots in the cauda equina constitutes a medical emergency (Box 15.5).

Investigations

NECK PAIN

Neck pain is less common than back pain but is a particular problem in elderly patients. It is usually due to mechanical or degenerative problems (Box 15.6). Nerve roots and/or the cervical cord may be compromised by osteophytes or disc prolapse (usually C6 disc compressing the C7 root). Surgery is occasionally required for severe radiculopathy or cervical myelopathy. The principles of investigation and management are similar to those for back pain.

15.6 CAUSES OF NECK PAIN ![]()

| Mechanical | e.g. Postural, ‘whiplash’, disc prolapse, cervical spondylosis |

| Inflammatory | e.g. Infection, spondylitis, RA, polymyalgia rheumatica |

| Neoplasia | e.g. Bony metastases, myeloma |

| Fibromyalgia | |

| Referred pain | e.g. Pharynx, teeth, angina, Pancoast tumour |

BONE PAIN

Causes of bone pain are listed in Box 15.7.

15.7 CAUSES OF BONE PAIN ![]()

| Cause | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Fracture (high-energy fractures, osteoporotic fractures, pathological fractures, e.g. secondary to bony metastases) | Acute pain, tenderness and deformity |

| Metastatic bone disease or primary bone tumour | Progressive, localised, associated weight loss and fatigue |

| Paget’s disease | Localised to affected sites +/− deformity |

| Osteomalacia | Bone tenderness and associated limb girdle weakness |

| Chronic infection (osteomyelitis) | |

| Renal bone disease |

MUSCLE PAIN AND WEAKNESS

It is important to distinguish between a subjective feeling of generalised weakness or fatigue, and ‘true’ weakness with objective loss of muscle power. The former is a non-specific manifestation of many organic diseases and also of psychological distress. The latter, however, may indicate intrinsic muscle disease. Proximal muscle weakness causes difficulty in standing from a seated position, squatting and lifting overhead. Distal power (e.g. grip) is usually preserved. Causes of proximal myopathy are listed in Box 15.8. Distal muscle weakness normally has a neurological cause.

15.8 CAUSES OF PROXIMAL MUSCLE PAIN AND WEAKNESS ![]()

| Inflammatory | e.g. Polymyositis, dermatomyositis |

| Endocrine | e.g. Hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, Cushing’s syndrome, Addison’s disease |

| Metabolic | e.g. Glycogen storage disorders, hypokalaemia, osteomalacia |

| Drugs/toxins | e.g. Alcohol, fibrates, statins |

| Infections | e.g. HIV, cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr, schistosomiasis |

| Genetic | e.g. Muscular dystrophies |

The most sensitive biochemical test of muscle injury is creatine kinase (CK). However, although a raised level confirms the suspicion of muscle inflammation or necrosis, it does not establish the cause. Muscle biopsy and electromyography (EMG) may therefore be required to reach a precise diagnosis.

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT OF MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS

Key aims of management of MSK conditions are:

These therapeutic objectives are achieved most effectively via a multidisciplinary team approach.

PHARMACOLOGICAL OPTIONS FOR DIRECT SYMPTOM CONTROL

NON-STEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS (NSAIDS)

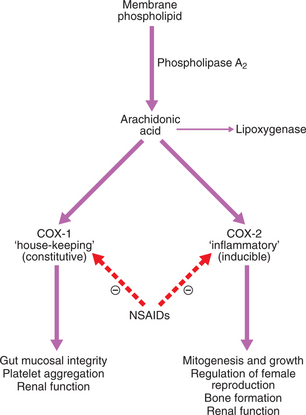

NSAIDs (e.g. ibuprofen, diclofenac) are effective in combating pain and stiffness associated with inflammatory disease. They also help reduce bone pain due to metastatic deposits. They act by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase (COX) and thereby reducing prostaglandin synthesis (Fig. 15.1). There are two isoforms of COX, encoded by distinct genes.

Details of the usage, dose and side-effects of NSAIDs are given on page 776.

OTHER ANALGESICS

Stronger analgesics are sometimes required for moderate to severe pain. The weak opioids codeine and dihydrocodeine are relatively mild analgesics, but may be effective when combined with paracetamol. Their use is often limited by side-effects such as constipation and confusion, particularly in the elderly. Continuous opioid use can give rise to dependence and tolerance. The centrally acting analgesic tramadol can also be useful for severe pain, but can cause nausea, constipation, dizziness, somnolence and confusion. Patients with refractory symptoms may merit referral to a specialist pain team.

SLOW-ACTING ANTIRHEUMATIC DRUGS

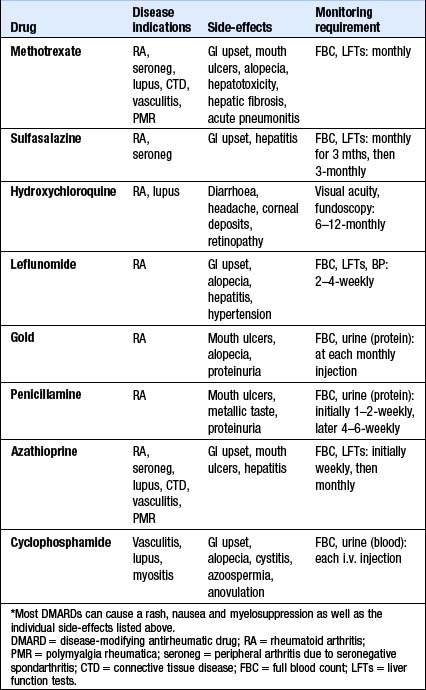

These drugs suppress chronic inflammatory disease, but can take several months to exert a beneficial effect. They may reduce target tissue damage and are therefore also called ‘disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs’ (DMARDs). They are used in the management of RA, seronegative spondarthritis and connective tissue diseases. All DMARDs carry potentially toxic side-effects, and regular monitoring is therefore required. Some of these drugs increase the risk of infection due to their immunosuppressant effect, and patients should therefore receive annual influenza vaccination, and pneumococcal vaccination every 5–10 yrs. The drugs may also compromise immunosurveillance, increasing the risk of solid tumours and lymphomas. Further details of individual DMARDs are given in Box 15.9.

OTHER TREATMENTS

CORTICOSTEROIDS

Glucocorticoids have a rapid and dramatic anti-inflammatory action. However, prolonged use is accompanied by an unacceptable level of side-effects, including the risk of iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome, steroid-induced diabetes and osteoporosis. Their use in MSK disorders is therefore generally reserved for rapid and short-term control of severe synovitis or systemic inflammation. They are also useful for control of inflammatory disease during pregnancy (when DMARDs are contraindicated) and for the treatment of polymyalgia rheumatica. Prednisolone is the oral steroid of choice. The aim is to use the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible time to avoid unnecessary side-effects.

OSTEOARTHRITIS (OA)

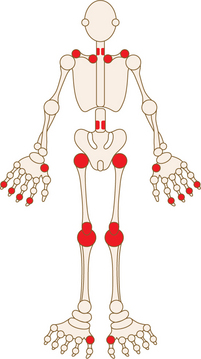

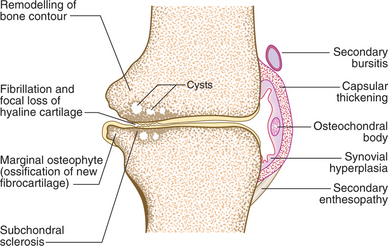

OA is by far the most common form of arthritis. It is strongly associated with ageing, with 80% of people over the age of 65 showing radiographic evidence of OA, although only 25–30% are symptomatic. It is characterised by focal loss of articular cartilage with new bone proliferation and remodelling of the joint contour. Inflammation is not a prominent feature. OA preferentially targets certain small and large joints (Fig. 15.2); the knee and hip are the principal large joints involved.

The pathogenesis of OA involves enzymatic degradation of aggrecan and collagen within the articular cartilage, with fissuring and thinning of the cartilage surface (Fig. 15.3). Cysts develop within the subchondral bone, possibly due to osteonecrosis resulting from increased pressure on the bone as the cartilage fails. At the joint margins there is new fibrocartilage production which then ossifies, forming osteophytes. Bone remodelling and cartilage thinning gradually alter the shape of the OA joint. This is commonly accompanied by wasting of the muscles acting across the joint, synovial hyperplasia and thickening of the joint capsule.

Clinical features

Nodal generalised OA: This common form of OA has a strong genetic predisposition and is more common in middle-aged women. Patients develop pain, stiffness and swelling affecting the finger interphalangeal joints (IPJs) (distal > proximal). Affected joints develop swellings which harden to become Heberden’s (distal IPJ) and Bouchard’s (proximal IPJ) nodes (Fig. 15.4). Involvement of the first carpometacarpal joint is also common. The condition is associated with a good functional prognosis. There is, however, an increased risk of OA at other sites (‘generalised OA’), especially the knee.

Investigations

Management

Treatment follows the principles set out on page 577 and includes:

INFLAMMATORY JOINT DISEASE

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS (RA)

RA is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis in women. The typical clinical phenotype of RA is a symmetrical, deforming, small and large joint polyarthritis, often associated with systemic disturbance and extra-articular disease. The clinical course is usually life-long, with intermittent exacerbations and remissions and highly variable severity. RA occurs throughout the world and in all ethnic groups. The prevalence is lowest in black Africans and Chinese; in Caucasians it is around 1.0–1.5% with a female : male ratio of 3 : 1. Prevalence increases with age, with 5% of women and 2% of men >55 yrs being affected. Concordance rates are higher in monozygotic twins (12–15%) than in dizygotic twins (3%). Up to 50% of the genetic contribution to susceptibility is due to genes in the HLA region, particularly HLA-DR4.

Clinical features

The diagnosis of RA is made clinically, and is supported by a raised ESR or CRP and, in the majority, a positive rheumatoid factor. The clinical hallmark of inflammatory joint disease is persistent synovitis. Diagnostic criteria for RA are listed in Box 15.10.

15.10 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS* ![]()

Diagnosis of RA is made with four or more of the following:

Other patterns of presentation also exist:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree