Overview

Musculoskeletal symptoms are very common, with lifetime prevalence rates of 75% or more for problems such as low back pain. Causes are frequently assumed, but are actually unpredictable and largely unknown. This makes outright prevention unfeasible

Explanations and diagnostic labels can negatively influence responses to symptoms. Care needs to be taken to reassure and emphasize the benefits of maintaining participation, and avoiding prolonged rest and inactivity

Clinical management should aim at symptomatic relief with maintenance of activity and work. Most interventions exhibit only weak to moderate treatment effects, and combining or repeating them does not seem to enhance effectiveness

Effective occupational management depends on communication and coordination between the key players, with optimal intervention being a combination of work-focused healthcare and accommodating workplaces

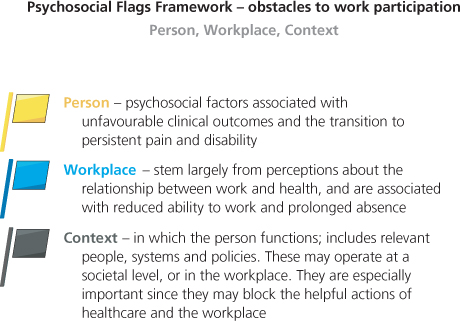

Psychosocial issues contribute most strongly to absence from work. These obstacles can be identified in three main areas: the person, their workplace and the everyday context in which they function. Actively tackling obstacles results in improved outcomes

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are commonly experienced across the population from childhood to old age, but are most frequently complained of to healthcare services by working-age people. They encompass the everyday aches and pains that are part of life as well as the consequence of specific injuries. MSDs can and do affect capability for work, both short and long term. They are a principal reason for sickness absence, yet they vary inconsistently by occupation. In terms of self-reported ill health, MSDs dominate the conditions that people believe are caused or made worse by their current or past work (despite the lack of evidence for direct causation). The occupational impact of MSDs has been stubbornly resistant to reductions in occupational physical exposures and increased access to healthcare. This suggests that simply focusing on ever more prevention and treatment is inappropriate. Instead, the ongoing challenge of managing work-relevant MSDs requires innovative and collaborative approaches from both healthcare and the workplace.

What the Epidemiology Tells Us

The musculoskeletal problems most frequently reported in the workplace are low back pain, neck pain and upper limb pain; lower limb problems are less frequently reported.

The lifetime prevalence of bothersome back pain is of the order of 75%, but occasional aches and pains are probably a universal experience. In the general adult population, over 40% can be expected to experience back symptoms during the course of a month, with the daily prevalence being up to 30% (Figure 8.1). The annual incidence rate (those developing a new episode) in the UK adult population is some 36%. Many children also experience back pain, and by adolescence over 50% will have experienced one or more spells. Thus, irrespective of occupational exposure a large proportion of the population will experience an episode of back pain over any given period. Leg pain (in the form of referred pain) will accompany back pain in perhaps 35% of cases, but lifetime prevalence of true radicular pain (sciatica) is only about 5%.

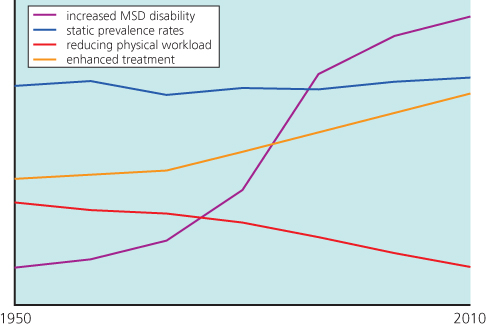

Figure 8.1 Paradoxical increased disability despite enhanced ergonomics and healthcare. MSD, musculoskeletal disorder.

The pattern is similar for neck and upper limb disorders, with a similarly high lifetime prevalence of bothersome pain somewhere in the upper limb. The proportion of people who experience some level of upper limb and neck pain during the course of a week is of the order of 44% (24% for neck pain and shoulder pain; 11% for elbow pain; 21% for wrist/hand pain), and most of them (70%) will find normal activities (including work) difficult or impossible. There are a number of conditions affecting the upper limb that, in the UK, are termed prescribed diseases (see Chapters 1 and 5) which is where the strength of the relationship with a particular occupation is considered to indicate an occupational risk for the purposes of certain benefits. Unfortunately, there is considerable uncertainty over classification and diagnosis for upper limb disorders, with inconsistent and inaccurate terminology confounding studies of their epidemiology, treatment, and management. Stated simply, upper limb disorders, whether specific diagnoses or non-specific complaints, are common entities, irrespective of work.

The epidemiological evidence strongly suggests that most musculoskeletal cases are characterized by complaints of symptoms, for which it is often not possible to objectively demonstrate an underlying pathology. Symptoms tend to coexist at numerous anatomical sites, but that is not to imply a common genesis. MSDs tend to be recurrent in nature, describing an untidy pattern of episodes having variable frequency, severity and impact. For most episodes, most people do not seek healthcare and do not require time off work: if they did there would be few people at work! The various presentations of MSDs—presence of symptoms; reporting of symptoms; attribution to work; sickness absence; prolonged disability; wellbeing—are generally independent of the medical condition; rather they are dominated by psychosocial factors—arising from the person, their workplace and the context in which they function (Figure 8.2).

Why People Experience Musculoskeletal Disorders

The onset of symptoms may be sudden and associated with activity, either trivial or strenuous. Onset can also be gradual with no identifiable triggering event. That said, it is common experience that some physical stress, often an everyday action, can precede the onset of acute symptoms. Overall, though, the causative mechanisms are unpredictable and largely unknown, so strategies aimed at preventing symptoms arising are destined to have limited overall impact. This does not mean they do not have a role, but it does mean that overall reliance on a primary prevention strategy will disappoint. Rather, the focus needs to broaden with adoption of a much smarter approach to prevention: one that meaningfully brings to life the adage ‘work should be comfortable when we are well and accommodating when we are sick or injured’.

The ubiquity and natural history make it very difficult to differentiate everyday experiences from work-induced symptoms (Box 8.1). Many musculoskeletal symptoms are perceived as ‘work related’, but causation is complex and relationships to purported physical risk factors at work remains, in most instances, unsupported by the epidemiology. That is, self-reported attributions are often unreliable and tend to overestimate work as the cause of any musculoskeletal condition. Nevertheless, MSDs are frequently work relevant in that some aspects of the work may be temporarily difficult, painful or impossible. Beliefs that a health condition is work related can be a major obstacle to continuing or returning to that job, irrespective of whether they are correct. The ‘injury model’ and attribution to work dominate contemporary thinking, a situation generally reinforced by the availability of benefits and compensation.

- Primary prevention of musculoskeletal symptoms is largely unfeasible

- most episodes are not caused directly by work

- Symptoms may affect ability to work

- symptoms may be more pronounced at work

- work may be difficult because of symptoms

- consequences are driven more by psychosocial than physical factors

- symptoms may be more pronounced at work

- Musculoskeletal problems may be work-relevant, irrespective of cause

Assessment and Classification Issues

Depending on the context, common MSDs are variously referred to in terms of symptoms, injury or pathology (Box 8.2). There is a wide spectrum of classification systems, ranging from specific disorders (diagnoses) to descriptive syndromes (non-specific), as well as a plethora of colloquial labels. However, most cases actually fall under the rubric non-specific.

Concept messages

- Musculoskeletal symptoms are a common experience—although symptoms are often triggered by physical stress (minor injury), recovery and return to full activities can be expected: activity is usually helpful: prolonged rest is not

- Work is not the predominant cause—although some work will be difficult or impossible for a while, that does not mean the work is unsafe: most people can stay at work (sometimes using temporary adjustments), but absence is appropriate when job demands cannot be tolerated

- Early return to work is important—it contributes to the recovery process and will usually do no harm; facilitating work retention and return to work requires support from workplace and healthcare

- All players onside is fundamental—sharing goals, beliefs and a commitment to coordinated action

Process messages

- Promote self-management—give evidence-based information and advice—adopt a can-do approach, focusing on recovery rather than what’s happened

- Intervene using stepped care approach—specific treatments only if required for particular diagnoses (beware detrimental labels and over-medicalization); encourage and support early activity; avoid prolonged rest; focus on participation, including work

- Encourage early return to work—stay in touch with absent worker; use case management principles; focus on what worker can do rather than what they can’t; provide transitional work arrangements (only if required, and time-limited)

- Endeavour to make work comfortable and accommodating—assess and control significant risks; ensure physical demands are within normal capabilities, but don’t rely on ergonomics alone; accommodating cases shows more promise than prevention

- Overcome obstacles—principles of rehabilitation should be applied early: focus on tackling biopsychosocial obstacles to participation—all players communicating openly and acting together, avoiding blame and conflict

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree