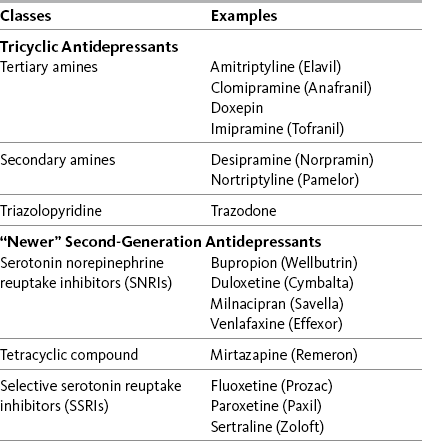

Chapter 22 DATA supporting the analgesic efficacy of some adjuvant drug classes are derived from numerous studies of very diverse syndromes. These drugs may be termed multipurpose and can be considered for any type of pain, fundamentally similar in this way to the opioids and nonopioid analgesics (Portenoy, 2000). The multipurpose adjuvant analgesics that are currently considered to be among the more useful in clinical practice include antidepressants, corticosteroids, and alpha2-adrenergic agonists (e.g., clonidine). Many of the multipurpose adjuvant analgesics are appropriate for both acute pain and persistent pain. Antidepressants have a delayed onset of analgesia, making them inappropriate for acute pain. Other drug classes, such as the sodium channel blockers and cannabinoids, have evidence to suggest broad applicability, but conventional use continues to position them solely for neuropathic pain (Lussier, Portenoy, 2004). Although the use of topical drugs is restricted by the location of pain, there are many types, and, combined, they too may be considered to have multiple purposes (see Chapter 24). See Table V-1, pp. 748-756, at the end of Section V for the characteristics and dosing guidelines for many of the multipurpose adjuvant analgesics. Antidepressant adjuvant analgesics are usually divided into two major groups: the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and the newer biogenic amine reuptake inhibitors (Table 22-1). Of the latter group, the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are clearly analgesics, whereas research is lacking or inconsistent regarding the analgesic potential of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (Arnold, 2007; Collins, Moore, McQuay, et al., 2000; Kroenke, Krebs, Bair, 2009; Saarto, Wiffen, 2007; Veves, Backonja, Malik, 2008). Table 22-1 Antidepressant Adjuvant Analgesics: Classes with Examples of Drugs From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 637, St. Louis, Mosby. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. An early systematic review of randomized controlled trials summarized the compelling evidence that antidepressants are efficacious in varied types of neuropathic pain (McQuay, Tramer, Nye, et al., 1996). Antidepressants are now identified as first-line analgesics in neuropathic pain guidelines (Dworkin, Backonja, Rowbotham, et al., 2003; Dworkin, O’Connor, Backonja, et al., 2007; Moulin, Clark, Gilron, et al., 2007). Anticonvulsants are another first-line choice for neuropathic pain and are discussed later in this section (see Chapter 23). Several excellent systematic reviews, some with related evidence-based guidelines for drug selection, provide additional support for the use of antidepressants in the management of neuropathic pain (Finnerup, Otto, McQuay, et al., 2005; Saarto, Wiffen, 2007; Kroenke, Krebs, Bair, et al., 2009). Data from another systematic review showed that there is no difference between antidepressants and anticonvulsants in the likelihood of achieving pain control (Chou, Carson, Chan, 2009). • The number-needed-to-treat (NNT) when TCAs are studied as analgesics for varied types of neuropathic pain averages 3.6 (95% CI 3 to 4.5), which means that it is necessary to treat 3 to 4 patients to find one who gets at least a 50% reduction in pain; in other words, one-third of patients with neuropathic pain who take TCAs achieve moderate pain relief. • Amitriptyline has been the best studied TCA, and in a range of doses up to 150 mg/day (10 studies, 588 patients), this drug has an NNT of 3.1 (95% CI 2.5 to 4.2). • Studies of painful HIV-related neuropathy have not confirmed the efficacy of the TCAs. • Analgesic doses for TCAs are typically less than antidepressant doses, and the effect on pain can be independent of any effect on depression. • Although several small studies have suggested that analgesic efficacy correlates with dose, dose-response data have not been established; nonetheless, TCAs must be titrated in individual patients to identify responders and, within the group of responders, achieve the most effective dose (gradual titration also reduces the risk of adverse effects and is especially important in older patients). • Across studies (N = 453), 13% of participants dropped out of active groups for a variety of reasons including intolerable adverse effects; discontinuation of dosing due to adverse effects is likely to be more prevalent in clinical populations, and prescribers usually attempt to select specific drugs based on relatively more favorable adverse effect profiles. • Postherpetic neuralgia (Argoff, Backonja, Belgrade, et al., 2006; Bowsher, 2003; Collins, Moore, McQuay, et al., 2000; Dubinsky, Kabbani, El-Chami, et al., 2004; Rowbotham, Reisner, Davies, et al., 2005) • Painful diabetic neuropathy (Boulton, Vinik, Arezzo, et al., 2005; Collins, Moore, McQuay, et al., 2000; Duby, Campbell, Setter, et al., 2004; Max, Culnane, Schafer, et al., 1987; Max, Lynch, Muir, et al., 1992) • Fibromyalgia (Arnold, 2007; Nishishinya, Urrutia, Walitt, et al., 2008; Hauser, Bernardy, Uceyler, et al., 2009; Heymann, Helfenstein, Feldman, 2001; Uceyler, Hauser, Sommer, 2008) (see also Hauser, Thieme, Turk, 2009) • Migraine and other types of headache (Ashina, Bendtsen, Jensen, 2004; Descombes, Brefel-Courbon, Thalamas, et al., 2001; Keskinbora, Aydinli, 2008; Krymchantowski, Silva, Barbosa, et al., 2002) • Arthritis (Frank, Kashini, Parker, et al., 1988; Katz, Rothenberg, 2005; Simon, Lipman, Caudill-Slosberg, et al., 2002) • Central spinal cord injury pain (Cardenas, Warms, Turner, et al., 2002) • Central post-stroke pain (Frese, Husstedt, Ringelstein, et al., 2006; Kumar, Kalita, Kumar, et al., 2009) • Persistent facial pain (List, Axelsson, Leijon, 2003) • Cancer-related neuropathic pain (Miaskowski, Cleary, Burney, et al., 2005; Ventafridda, Bonezzi, Caraceni, et al., 1987) • Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy (Note: 50 mg/day was thought to be too low to produce positive effects) (Kautio, Haanpaa, Saarto, et al., 2008) • Interstitial cystitis (van Ophoven, Pokupic, Heinecke, et al., 2004) • As mentioned, antidepressants are not appropriate for treatment of acute pain because of the delay in time before appreciable analgesia. However, although not approved for use in the United States at the time of publication, a phase I trial of IV amitriptyline established the safety of a 25 mg to 50 mg preoperative infusion (Fridrich, Colvin, Zizza, et al., 2007). (See amitriptyline patient medication information, Form V-1 on pp. 759-760, at the end of Section V). Desipramine (Norpramin) is a secondary amine TCA. It has relatively more effect on norepinephrine reuptake than amitriptyline and usually causes fewer adverse effects. (See desipramine patient medication information, Form V-5 on pp. 767-768, at the end of Section V). Clinical reviews and single studies have shown its efficacy in the following: • Postherpetic neuralgia (Collins, Moore, McQuay, et al., 2000; Dubinsky, Kabbani, El-Chami, et al., 2004; Max, Lynch, Muir, et al., 1992; O’Connor, Noyes, Holloway, 2007; Zin, Nissen, Smith, et al., 2008) • Painful diabetic neuropathy (Argoff, Backonja, Belgrade, et al., 2006; Boulton, Vinik, Arezzo, et al., 2005; Collins, Moore, McQuay, et al., 2000; Duby, Campbell, Setter, et al., 2004; Zin, Nissen, Smith, et al., 2008) • Cancer-related neuropathic pain (Miaskowski, Cleary, Burney, et al., 2005) Nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor) also is a secondary amine compound. (See nortriptyline patient medication information, Form V-10 on pp. 777-778, at the end of Section V). It has been researched for the following types of pain: • Fibromyalgia (Heyman, Helfenstein, Feldman, 2001) (See also Hauser, Thieme, Turk, 2009.) • Postherpetic neuralgia (Dubinsky, Kabbani, El-Chami, et al., 2004) • Painful diabetic neuropathy (Boulton, Vinik, Arezzo, et al., 2005) • Persistent lumbar radiculopathy (Khoromi, Cui, Nackers, et al., 2007) • Cancer-related neuropathic pain (Miaskowski, Cleary, Burney, et al., 2005) • Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy (Hammack, Michalak, Loprinzi, et al., 2002) Although an early review concluded that research does not provide convincing support for the use of antidepressants for musculoskeletal pain (Curatolo, Bogduk, 2001), later research calls for further evaluation of duloxetine for osteoarthritis (OA) pain (Sullivan, Bentley, Fan, et al., 2009). Patients in the latter study were given two weeks of placebo followed by 10 weeks of duloxetine. Self-reported function improved, and pain intensity was reduced 30% as measured on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) between 2 and 12 weeks of treatment. Similarly, improvements in pain (30%) and physical function were found in patients who received duloxetine in another randomized, placebo-controlled trial (Chappell, 2009). More and larger studies on the use of duloxetine for this type of pain are needed. (See duloxetine patient medication information, Form V-6 on pp. 769-770, at the end of Section V). In a study of experimental pain, venlafaxine (Effexor) increased pain tolerance (Enggaard, Klitgaard, Gram, et al., 2001), and in a study of patients with neuropathic pain, the drug reduced hyperalgesia and temporal summation (repeated neuronal stimulation and action potentials) but not intensity and pain detection thresholds (Yucel, Ozyalcin, Talu, et al., 2005). Electrocardiogram (ECG) changes have been associated with venlafaxine, so cautious use in patients with high cardiovascular (CV) risk is recommended (Dworkin, Backonja, Rowbotham, et al., 2003). (See venlafaxine patient medication information, Form V-12 on pp. 781-782, at the end of Section V). Among the studies of venlafaxine for the treatment of pain are the following: • Persistent pain and associated depression (Bradley, Barkin, Jerome, et al., 2003) • Painful diabetic neuropathy (Davis, Smith, 1999; Duby, Campbell, Setter, et al., 2004; Dworkin, Backonja, Rowbotham, et al., 2003) • Postherpetic neuralgia (Dworkin, Backonja, Rowbotham, et al., 2003) • Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (Durand, Alexandre, Guillevin, et al., 2005) • Neuropathic back pain (Pernia, Mico, Calderon, et al., 2000; Sumpton, Moulin, 2001) • Persistent pelvic pain (Karp, 2004) • Tension headaches (Zissis, Harmoussi, Vlaikidis, et al., 2007)

Multipurpose Adjuvant Analgesics

Antidepressant Drugs

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs)

Amitriptyline

Desipramine

Nortriptyline

“Newer” Antidepressants

Duloxetine

Venlafaxine

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree