Chapter 5

Multimorbidity and the Primary Care Clinic

Stewart W. Mercer1 and Chris Salisbury2

1General Practice and Primary Care, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, UK

2Centre for Academic Primary Care, NIHR School for Primary Care Research, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, UK

Overview

- Primary care is largely organized around the needs of patients with single conditions, and thus patients with multimorbidity are like square pegs trying to be fitted into round holes

- Practices need to organize their care differently, putting the multimorbid patient at the centre of the system

- There is an urgent need to move from reactive to anticipatory care and from disease-centred approach to a holistic patient-centred approach

- This requires multiple changes at system, practitioner and patient levels

- Consultation length may need to be substantially increased for multimorbid patients combined with relational and informational continuities

- Self-management support needs to be enhanced both within consultations and by better links with community resources (community-facing primary care)

- In areas of high socio-economic deprivation, the problems facing multimorbid patients within primary care are exacerbated by the ‘inverse care law’, in which higher needs and demands result in poorer access, shorter consultations, lower patient enablement and increased GP stress.

Background

It will be clear by now from reading the previous chapters that although multimorbidity is the norm rather than the exception in patients with long-term conditions, healthcare systems remain largely configured around a single-disease model. The patient with multimorbidity can be compared to that of a square peg trying to be fitted into a series of round holes. The needs of multimorbid patients are often complex, involving not only several physical conditions but also psychological and social problems. Thus, the needs of patients with multimorbidity are likely to be best met by a holistic approach, based around generalist primary care.

So what is needed at practice level?

Since most health care received by multimorbid patients comes from primary care and general practitioners (GPs) in particular, the following discussion focuses mainly on the organization of general practice and primary care, although many of the issues are likely to be of similar importance in secondary care. Describing what is needed in the organization of care for patients with multimorbidity may be best illustrated by first thinking about what is not needed – yet is often what multimorbid patients encounter. What is not needed is rushed, fragmented episodic and reactive care delivered with a single-disease biomedical focus, with no coordination between providers and services and no regard for the burden imposed on the patient, nor the patients’ views and priorities (see Box 5.1).

Box 5.1 Example of reactive care of a multimorbid patient

- Mr. D is a 58-year-old man who works night shift in the local supermarket staking shelves and suffers from COPD, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and back pain.

- He books an ‘emergency’ (same day) appointment to see Dr Y at his practice, a doctor he has never met before.

- The doctor is running 30 min late when he calls Mr. D into his consulting room.

- Mr. D explains that he has come about his cough and shortness of breath, and is finding it hard to cope with work because of this and his back pain. He is also finding it hard to sleep at home as high-rise flat he lives in is very noisy during the day.

- Dr Y only enquires about the cough, its duration, whether he is coughing up nasty coloured sputum or blood and his shortness of breath. He carries out a perfunctory examination of Mr. D’s chest and tells him that he has a chest infection.

- He prescribes antibiotics and oral steroids, and a benzodiazepam to help him sleep. He gives him a sick note for two weeks saying ‘unfit for work’ but without any suggestions regarding a phased return to work or lighter duties.

- Dr Y is looking at his watch and ushers Mr. D out of his room, telling him to come back to see one of the doctors if things do not settle down.

What is needed of course is the complete reverse of this. Patient-centred care in its broadest sense is what is most needed in the care of multimorbid patients such as Mr. D, and the organization of care within the consultation, the practice and beyond needs to reflect such a focus. The issues critical to this include staff and patients’ values and attitudes, the structure of consultations, consultation length, continuity and workload (on patients and healthcare staff). Practices can do much to organize the care they provide in a more patient-centred way, but many factors that influence this lie out with the remit of the GP or practice team. Policy and healthcare organization, on a macro-level, can greatly facilitate or hinder the possibility of optimal care for multimorbid patients and this is discussed in detail in Chapter 11.

How can this be achieved?

Moving from a reactive model of doctor (or nurse)-driven care to one that is anticipatory, inclusive, centred around the patient and his or her needs and priorities is no easy matter. Both financial and non-financial incentives may be important. Education and training of staff are also essential, as is the ‘education’ of patients as to what are realistic expectations, and honesty regarding what health care can and cannot achieve. Long-term conditions are by definition ‘incurable’ and patients should expect to receive holistic care that is responsive to their needs and priorities, but also need to recognize that doctors can only do so much, and they also have an important role as active participants in their own health and health care. However, we must caution against the development of a ‘blame culture’ and punitive actions against those who do not ‘self-manage’. There are many barriers to effective self-management support for multimorbid patients within healthcare systems (Box 5.2)

Box 5.2 What are the challenges of imbedding self-management support within consultations with patients with multimorbidity?

- GPs worry that suggesting self-management may harm the doctor–patient relationship.

- GPs report a lack of time in the consultation to give self-management support.

- In deprived areas, GPs and practice nurses see the management of multimorbidity as an ‘endless struggle’ with self-management being low on the patients agenda.

- Community support (i.e. voluntary sector) is often singe disease focused.

- Patients in deprived areas need more help in accessing community information and support but GPs may not know what is available locally.

Identifying patients and recall systems

The first task in moving from reactive to anticipatory care for patients with multimorbidity requires that there are mechanisms in place within the clinic to accurately identify patients with multimorbidity. The effective management of these patients requires well-organized medical records, which increasingly depend on electronic health records leading to paperless or at least paper-light practices (unlike the example shown in Figure 5.1!).

Figure 5.1 In many places, paper-based records remain the norm.

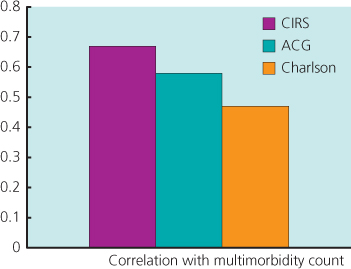

Although this may seem a simple task in practices with electronic medical records, as pointed out in Chapter 7, the systematic recording of patients with multimorbidity within the electronic medical record often does not happen. In the UK, for example registers are recorded according to single diseases that are included in the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). Searching the records to find which of these patients have multimorbidity is often difficult, especially when the conditions include those not currently included in the QOF targets. Thus, a primary task for practices, working in collaboration with IT providers, is to ensure that such searches can be done to identify target patients with multimorbidity and that recall systems are in place. This would ensure that it was then feasible to call specific patients for reviews, avoiding the common scenario of multimorbid patients being recalled to several single-disease clinics for review. An additional consideration is the burden of multimorbidity. The best way to measure and document multimorbidity burden routinely in clinical IT systems is not clear, but a simple count of the number of chronic conditions per patient correlates well with other validated measures of multimorbidity burden (see Figure 5.2). The best method of predicting health service utilization is also unclear but again, a simple count may be as predictive as other methods at least for certain outcomes (Table 5.1).

Figure 5.2 Relationship between number of chronic conditions and measures of burden. Unpublished data from Stewart W. Mercer on 200 primary care patients with multimorbidity in Scotland. Correlations between total multimorbidity count and all three measures of burden were significant (P < 0.001).

Table 5.1 Relationship between different measures of multimorbidity burden and health service utilization.

| Number of GP clinic visits | Number of prescribed drugs | Number of blood tests | Number of hospital out-patient visits | Number of A + E (Accident and Emergency) visits | Number of unplanned hospital admissions | |

| Multimorbidity count | 0.56*** | 0.64*** | 0.59*** | 0.32** | 0.28** | 0.28** |

| CIRS | 0.63*** | 0.71*** | 0.61*** | 0.28** | 0.24* | 0.32** |

| Charlson | 0.41*** | 0.48*** | 0.25** | 0.32** | 0.24* | 0.22* |

| ACG | 0.68*** | 0.68*** | 0.48*** | 0.39*** | 0.38*** | 0.34*** |

Unpublished data from Stewart W. Mercer, on 106 general practice patients in Scotland. Results show Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rho).

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Informational and relational continuity

The second task in developing a patient-centred practice for multimorbidity is to have a system in place that supports continuity of care. Informational continuity, in which key information about a patient is held within the clinical record, so that different doctors within the practice can access this information, is of course a basic pre-requisite of any attempt at improving continuity. However, for many patients with multimorbidity, relational continuity is important to both patient and doctor. For the patient, seeing the same doctor at each visit or most visits decreases the need to repeat their story and enhances trust and the development of a therapeutic relationship. For the doctor, it is also important clinically and interpersonally, and can save time as old ground does not need to be gone over at each meeting. With changes in practice, such as a greater emphasis on rapid access to care and more GPs and healthcare staff working part-time, relational continuity can be hard to achieve. However, for multimorbid patients having a lead GP (and in secondary care a lead specialist) that the patient sees most of the time, with one or two other GPs that they see when the lead GP is not available, would be an improvement. This would then require that the GPs responsible for the care of that patient were kept well informed about decisions made (i.e. communication between GPs within the practice would be required) and can act as an overall coordinator of care.

Healthcare systems can promote or hinder continuity of care (Boxes 5.3 and 4).

Box 5.3 Improving continuity of care for patients with multiple conditions in general practice (data from Hill and Freeman 2011).

- Ensure that patients with multimorbidity understand that doctors find it easier to provide good care for patients they know well. This is especially important for people from socio-economically deprived populations who have the greatest burden of illness, the greatest need for continuity of care and the lowest ability to navigate administrative barriers which may get in the way of them seeing a regular doctor.

- Change receptionists’ behaviour and the prompts on booking systems so that the patient’s ‘own doctor’ becomes the default option.

- Organize large practices into small teams of two or three doctors who see each other’s patients when one is away. Ensure that patients know about these arrangements.

- Identify patients with particularly complex problems who should only be seen by a restricted number of doctors. Adjust the appointment system so that they cannot be booked into other doctors. Explain this to the patients, this means they may have to wait longer for an appointment but they will get better care for their complex problems.

- Develop better questions on continuity of care in patient surveys and make sure they are included in patient assessments of care. Where countries have arrangements for regular appraisal of doctors or periodic revalidation or recertification, include questions on how a doctor’s practice is organized to provide continuity of care for people with complex problems.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree