Chapter 7

Multimorbidity and the Healthcare Electronic Medical Record

Amanda L. Terry1 and Sonny Cejic2,3

1Centre for Studies in Family Medicine, Department of Family Medicine and Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, The University of Western Ontario, Canada

2Department of Family Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, The University of Western Ontario, Canada

3Byron Family Medical Centre, Canada

Overview

- Current electronic medical record (EMR) systems are limited in their capacity to support the care of patients with multimorbidity

- EMRs need to be used comprehensively and integrated fully into healthcare practice to maximize their usefulness

- Information should be entered into EMRs in a way that it supports comprehensive use – this is the foundation for allowing practitioners to begin to harness the power of the EMR

- Computer-based technology, in the form of advanced EMRs, is necessary to support the complexity of care required by patients with multimorbidity.

The electronic medical record (EMR) is a specialized kind of computer software that is used by health care practitioners to support the care of their patients. Current EMR systems are generally structured to reflect a single-disease orientation and are used in this way by primary healthcare practitioners. This is a significant limitation as some of the functions of current EMRs, for example, algorithms to identify patients with specific conditions, are too simplistic to use with patients who have multimorbidity. However, this is the current reality of EMR use in primary health care. Therefore, this chapter focuses on the use of EMRs in the care of patients with multimorbidity from two perspectives: (1) maximizing the use of current EMRs, and (2) how future EMRs could better support the care of these patients.

How can existing EMR technology be best used for the care of patients with multimorbidity?

To best use the current EMRs to support the care of patients with multimorbidity, it is important to pay attention to five key tasks as follows (Terry et al. 2012).

- Use the EMR comprehensively in day-to-day practice

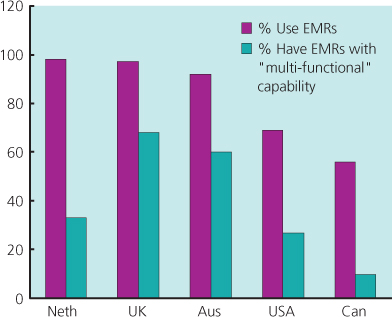

This means using all of the parts of the software program that are available and clinically relevant to the fullest extent possible. Currently, many practitioners do not use their EMRs fully (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Primary care physician EMR use – comparison in five countries.

Data from Schoen et al. 2012.

To achieve more comprehensive use, primary healthcare practitioners should: (1) engage in targeted software training, (2) have a ‘super-user’ or coach, someone who can help in the use of the EMR software, (3) have a system whereby feedback reports are created; for example, immunizations completed for all patients, on a regular basis. This allows the practitioner to both reflect on the quality of the information being entered and to develop skills in retrieving information from the EMR.

- Organize the practice to support the tasks that emerge from EMR use

Organization involves attending to change the management processes, including workflows and the re-organization of human resources. For example, if reminders are generated within the EMR for follow-ups in patient care, how can these tasks be handled by the practice? What resources need to be in place to support this work?

- Attend to and coordinate data entry practices

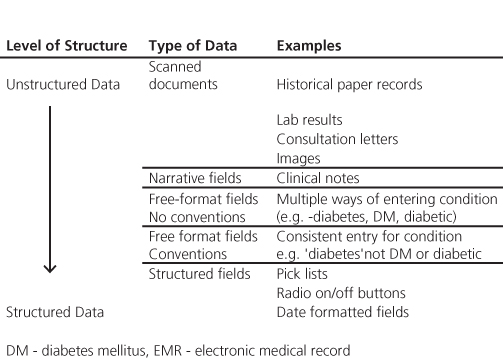

Attend to data entry practices and coordinate these with the practices of the larger primary healthcare team (Ryan et al. 2011). For example, the recording of information using structured data (using systems such as the International Classification of Primary Care) versus information recorded in an unstructured or narrative manner (Figure 7.2).

Periodic chart audits should be conducted to assess the quality of data that is recorded.

- Organize patient summaries

Organize patient summaries in the problem list so that it immediately becomes apparent that the patient has multimorbidity when the chart is opened. It is also important to understand how the coding of this list in the practitioner’s particular EMR works – is the coding specific enough that the nature of the multimorbidity is clear? As an additional step, review patient summaries and problem lists regularly.

- Include the EMR in the encounter

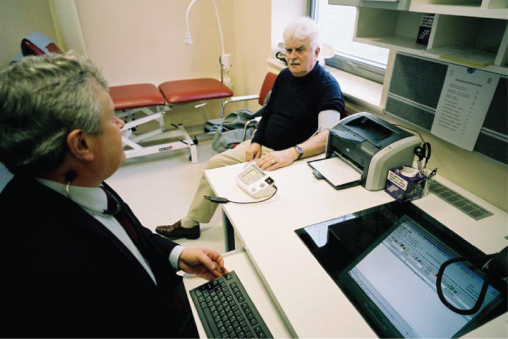

Finally, how the EMR is used in the encounter with the patient, particularly in terms of how the information is gathered from the patient, can affect the quality of the information in the EMR. For this reason, the practitioner needs to attend to the interaction of themselves with the patient and the EMR during the encounter. There are three main things to keep in mind: (1) the structure of the space used for the interview, (2) the attentiveness of the practitioner to the computer and the patient and (3) the way the patient interacts with the computer (Figures 7.3 and 7.4).

Figure 7.2 Taxonomy of EMR data structure.

Source: Ryan et al. (2011). Reproduced by permission from College of Family Physicians of Canada.

Figure 7.3 Modern IT systems are essential for high-quality care of multimorbid patients, but the way computers are used within the consultation is also important.

Figure 7.4 In the treatment room, patients cannot compete with a computer.

Source: http://www.drmussey.com/ (as appeared in The Free Lance Star May 27, 2011). Reproduced with permission from Dr Steven Mussey.

How could future EMRs better support the care of patients with multimorbidity?

There are three key areas within which EMRs and accompanying information technology could evolve to better support the care of patients with multimorbidity: (1) improved primary healthcare practitioner and patient access to the EMR, (2) enhanced EMR capacity to support team-based care and information needs and (3) advanced EMR functioning to facilitate patient care.

Improved access to the EMR

Improvements in the access to the EMR are needed to facilitate the use of this technology by practitioners and patients. Practitioners need to be able to access the EMR remotely during out-of-office activities or in-home patient visits using multiple methods; for example, via hand-held devices or secure websites. Patients need to be able to view their medical records, enter data into the EMR, confirm information that is present and to engage in self-monitoring activities potentially through individualized access to specific areas of the EMR. One way patient data may be entered in the EMR is through home clinical measurement devices; for example, an electronic blood pressure cuff could measure values and send the information securely to the practitioner’s EMR (Figure 7.5). Finally, primary healthcare practitioners need to be able to communicate directly with the patients using electronic means such as secure emailing, texting and messaging within the patient-accessed areas of the EMR.

Figure 7.5 Example of a blood pressure cuff (Withings Smart Blood Pressure Monitor).

Enhanced EMR capacity to support team-based care and information needs

Team-based care is a key aspect of providing excellent primary health care for patients who have multimorbidity; future EMRs need to be configured to support this type of care. In addition, EMRs need to support the information needs of practitioners in the care of patients with multimorbidity. To achieve these goals, several developments are required. ‘User-friendly’ EMRs need to be designed that facilitate team-based care, with features such as a shared medical problem-coding system among practitioners, and support for the data entry and care-provision needs of different practitioners. Electronic communication and appropriate electronic exchange of information among practitioners are also necessary to support team-based care. Ease of information entry is important; for example, having the computer-coding information in the background while the practitioner is caring for the patient in the encounter. To facilitate care, key elements in the problem list and patient history should be tailored to the individual patient’s characteristics and should be immediately available when the practitioner opens the patient’s chart. In addition, the EMR needs to present summaries of patient information to the practitioner; for example, flagging out-of-range clinical values for that individual.

Advanced EMR functions

Care of patients with multimorbidities also requires a shift in clinical thinking – away from a focus on individual conditions to that of the complex reality of patients with multiple and co-occurring conditions. EMRs need to be designed to mirror this reality. An ‘active EMR’ with advanced functions could be developed to support the care of patients with multimorbidity, where information specific to the individual patient would be continually sought, analyzed and summarized by the computer. For example, the EMR could scan the literature for recent changes in medical evidence and present lists of patients to the practitioner who are affected by these changes. This could facilitate follow-up activities by the practitioner; for example, sending a secure email to a patient who needs a medication change. In addition, the EMR could calculate probabilities of potential diagnoses of multimorbidity and display them to the practitioner when the patient is present. This would be based on information entered in the EMR; for example, test results, history, symptoms and diagnoses from specialists.

New algorithms to warn a practitioner of concerning interactions could be developed as part of this kind of EMR. Similar to the medication-to-medication interaction function, medication-to-disease interaction checks for patients with multiple conditions and medications could be implemented. For example, an alert stating the consequences of prescribing a beta-blocker medication in a patient with asthma or sick-sinus syndrome. Within the patient encounter, the EMR could (1) provide ideal decision support, by seeking information from best practice sources and summarizing the evidence for individual patients with multimorbidity to support the development of the care plan, (2) assist the practitioner by producing ‘care plan scenarios’ based on individual patients with specific clusters of conditions, (3) calculate the convergence and divergence among multiple clinical practice guidelines and (4) present options for the optimal management of patients with multimorbidity.

A recent commentary (Dawes 2010) suggests that ‘risk–benefit’ calculations could be conducted within an EMR and displayed for interventions suggested by each clinical practice guideline for an individual patient. This would allow the practitioner and the patient to make care plans based on an understanding of the implications of each intervention, given the multiple morbidities of the patient. Finally, and most importantly, the design of the EMR needs to facilitate the practitioner’s treatment of the patient as a ‘whole person’, reflecting the goals of the patient with multimorbidity.

Conclusion

This chapter outlines five key tasks, which are necessary to achieve comprehensive use of the EMR in the care of patients with multimorbidity and identifies several areas where EMRs need to evolve to better support the care of these patients. Focusing on the future, there are three key areas of innovation and change that will be associated with the use of EMRs for patients with multimorbidity. First, through individualized access to the EMR, patients will become more engaged in accessing, changing and validating health information held in their healthcare practitioner’s records or their own personal health records. Second, the evolving expectations of EMR users will result in an increased demand for EMR design that supports more efficient use and data entry. Finally, as use of EMR data continues to increase, the ability to interpret, validate and analyze data in the care of patients with multimorbidity will improve (Boxes 7.1 and 7.2).

Box 7.1 The management of the multimorbid patient in the year 2020?

You have known your patient John Brown for many years. He has diabetes, hypertension, asthma, atrial fibrillation and hypothyroidism and is on several medications including a blood thinner. He routinely sends you his home blood pressure and blood sugar readings taken by using his electronic measuring device securely through the Internet to your EMR. Today, you get a message from John through your EMR that he has been having some mild increase in shortness of breath over the past few days. Also, your EMR alerts you that John has a significant increase in his heart rate over the last few readings. You send a message to your nurse practitioner requesting them to review John’s chart and do a home assessment. In addition, you submit an electronic request to the lab technicians to visit John’s home and perform an ECG along with some blood tests. The nurse practitioner examines John at his home and uses a mobile computer to send you messages. It appears that John indeed has an increased heart rate with no other physical findings. The lab had just transmitted John’s ECG into your EMR as well. The ECG reports an irregular heartbeat compatible with rapid atrial fibrillation. John does not want to go to hospital for further assessment. While awaiting the blood results, you work on getting John feeling better by getting his heart rate under control. You start to prescribe a beta blocker but your EMR warns you of a drug–disease interaction, specifically, a potential worsening of asthma with the use of beta blockers. Instead, you use a calcium channel blocker. The prescription is electronically sent to the pharmacist and the medication is quickly delivered to John’s home. You monitor John more closely through his home devices and find that John’s heart rate has improved the next day. John sends you a message that he is feeling better. In addition, you get an alert from your chart that John’s blood work showed a significant hyperthyroid state. You talk to John by phone and find out that he has been incorrectly taking his thyroid medication with his recent medication renewal. You help him correct the problem and he thanks you for not having to go to hospital.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree