Chapter 6

Multimorbidity and Patient-Centred Care

Moira Stewart1 and Martin Fortin2

1Centre for Studies in Family Medicine, Western University, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western Centre for Public Health and Family Medicine, Canada

2Family Medicine Department, Université de Sherbrooke, Academic Research Director, Centre de Santé et de Services Sociaux de Chicoutimi, Canada

Overview

- Patient-centredness was born from the need to understand the patient’s experience and to integrate this experience into care

- A patient-centred approach to consultations avoids several common pitfalls encountered with multimorbid patients

- A patient-centred approach includes four components: exploring the diseases and the patients’ illness experience; understanding the whole person in context; finding common ground and enhancing the patient–practitioner relationship

- Research has shown that patient-centred consultations positively affect outcomes.

Introduction

Throughout the history of medicine two approaches have been used: a basic biomedical approach seeking answers to single pathologies, and a more Hippocratic approach seeking to place the pathology into a context that includes the patient’s experience and environment. Current manifestations of these broad approaches are evidence-based medicine-producing key guidelines of the quality of care for each chronic condition, and person-based medicine seeking to integrate the patient’s experience and context into care. A healthcare practitioner wishing to provide the best care for his or her patients with multimorbidity may need to find a way of incorporating or integrating these two broad approaches. The patient-centred clinical method offers such an integrated framework.

Box 6.1

What are the four principal components of the patient-centred consultation?

What are the outcomes that have shown to be positively affected by patient-centred care?

What are the common pitfalls that can be avoided with multimorbidity patients by using a patient-centred approach?

Patient-centredness is especially relevant to the care of patients with multimorbidity as the diseases and the illness experience form an interwoven pattern that is often impossible to disentangle and that should be dealt with as a whole. This chapter introduces the components of patient-centred care as a framework for the medical consultation adapted to the care of patients with multimorbidity.

Although several models of patient-centredness have been suggested, we present here the essential components as a guide to help organize the consultation of the general practitioner (GP) with multimorbid patients. However, these components are applicable to most if not all healthcare practitioners’ consultations. The consultation should focus on four essential components depicted in Figure 6.1: exploring the diseases and the patient’s illness experience including expectations; understanding the whole person in context; finding common ground including agreeing on competing priorities and enhancing the patient–GP relationship. The components are guides and, with each patient, they combine in an interconnected manner. Over time, a practitioner will weave back and forth among the four components in providing continuity of care.

Figure 6.1 Four components of patient-centred GP consultations.

Multimorbidity contributes to the particular context of a consultation because it evolves over time as old conditions may worsen or become salient and new conditions are added. Multimorbidity is chronic but unlikely to be stable. Patients are thus facing an increasingly complex experience over time, and it is therefore very important that the GP be patient-centred and adapt to this evolving challenge.

This patient-centred approach to the consultation avoids several common pitfalls encountered with multimorbid patients. It avoids too much attention on one disease at a time, a problem especially when some prevalent conditions require common management strategies, such as lifestyle modification. In addition, it avoids unnecessary subsequent recurring visits of patients, thus reducing healthcare costs. Also, it stresses the continuity of the relationship with the patient over many consultations, thereby helping to prevent feelings of failure and, even, abandonment, in patients when the conditions worsen. All in all, a focus on the person is more likely to meet patients’ needs (Box 6.1).

Justification for a patient-centred approach

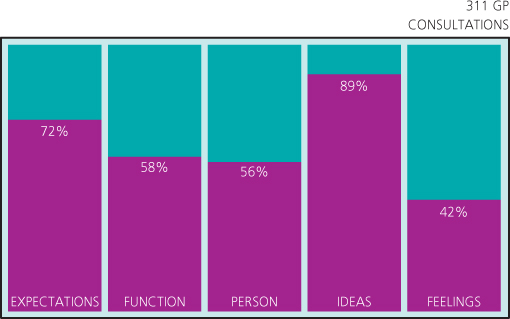

The main justification for a patient-centred approach is that it is the right approach to take − the moral imperative. As well, there are additional justifications. Firstly, patients expect consultations that include the four components listed earlier. Secondly, multimorbidity is so prevalent that an approach that addresses each chronic problem as separate and distinct makes no sense practically or conceptually. Akin to the second argument is the fact that the majority of GP patients have different sorts of illness experiences such as feelings, ideas about what is wrong, expectations of their health care, effects on their daily function and relevant contextual issues regarding family or work. Figure 6.2 demonstrates the magnitude of these relevant illness issues, driving home the notion that flexibility and a patient-oriented approach are necessary. Thirdly, research has shown that patient-centred consultations positively affect a list of important outcomes, desired by practitioners, patients and the healthcare system (see Box 6.2 for the list of outcomes).

Figure 6.2 Patient issues expressed during consultations with their GP.

First component: exploring diseases and the illness experience

One of the key problems in working with patients with long-term conditions is the somewhat false sense of security, because the

Box 6.2 Outcomes affected by patient-centred care

- – Patients are more satisfied

- – Patients report more positive experiences of their health care

- – Patients are more likely to adhere to the treatment plan

- – Patients report improved symptoms

- – Patients report decreased anxiety

- – Patients’ functional status improves

- – Utilization and costs decrease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree