Chapter 9

Multimorbidity and Mental Health

Peter Bower1, Peter Coventry2, Linda Gask1, and Jane Gunn3

1Centre for Primary Care, NIHR School for Primary Care Research, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, University of Manchester, UK

2NIHR CLAHRC for Greater Manchester, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

3Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care, Academic Centre Melbourne Medical School, The University of Melbourne

Overview

- Patients with long-term conditions have a high prevalence of problems such as depression and anxiety

- The presence of depression and anxiety can have significant implications for self-management of long-term conditions and quality of life

- There are important barriers to the recognition and management of depression and anxiety in patients with long-term conditions

- The management of depression and anxiety in patients with long-term conditions may be improved through the adoption of common principles of ‘chronic disease management’ and ‘collaborative care’.

Background

This chapter considers what is known about multimorbidity when long term conditions and mental health problems coexist and explores the challenges faced by clinicians and services to respond to the needs of patients.

Common mental health problems and long-term conditions

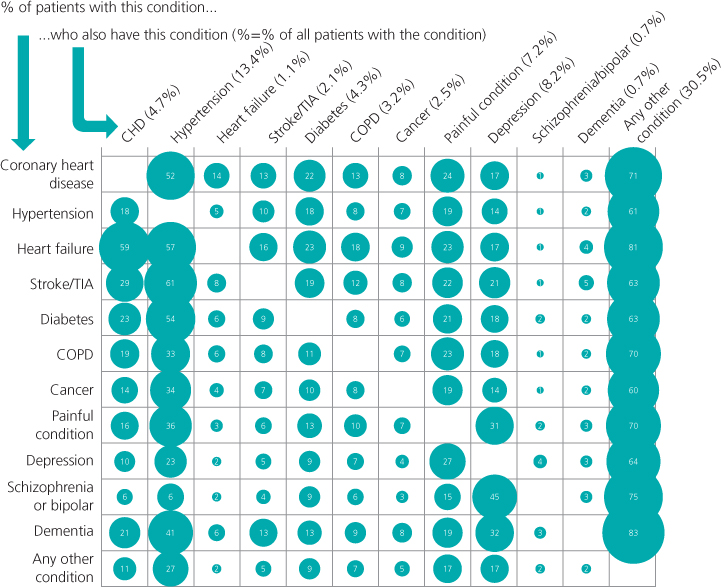

As Moussavi et al. (2007) have found, patients with long-term conditions have a high prevalence of major depressive illness. The co-occurrence of long-term conditions and mental health problems is shown in Figure 9.1. Many patients, like John in the case study in Box 9.1, may attribute the cause of their depression to reaction to a long-term condition and the limitations that it brings. However, depression and long-term conditions share a complex relationship. Long-term conditions can lead to depression, but depression is also an important risk factor for later long-term conditions. Less attention has been given to anxiety even though symptoms of anxiety and depression are highly correlated, and ‘mixed anxiety and depression’ is very common in primary care.

Figure 9.1 Co-occurrence of physical and mental conditions in primary care patients.

Source: Barnett et al. 2012. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.

Box 9.1 Case example – depression and long-term conditions

John is a 48-year-old labourer with coronary heart disease. John has put on weight and is not adherent with his medication, and his nurse is concerned that he is putting himself at risk. His general practitioner (GP) conducts a mental health assessment, including the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ 9), which is a short self-report measure of depressive symptoms.

His PHQ 9 score is 19, indicating moderately severe depression. Although John accepts that the PHQ score is a fair reflection of the way he feels, he is resistant when the term ‘depression’ is mentioned. He does not feel that he has a ‘mental illness’ and states categorically that the way he feels reflects the impact of coronary heart disease on his work and personal life, and his everyday pleasures such as drinking and smoking. He feels that it is these issues that are making him feel down, and if there were better ways of managing his heart problems, the feelings would disappear.

The clinical implications of common mental health problems in long-term conditions

Irrespective of controversies over cause and effect, the major concern of clinicians is on the impact of mental health and long-term conditions on patient experience, mortality and morbidity, and quality of life.

The UK Department of Health defines self-management as ‘the care taken by individuals towards their own health and well being’ and includes a healthy lifestyle, social and emotional needs, managing the condition and prevention. Depression can reduce motivation and capacity for self-management and poor outcomes in people with comorbid depression alongside long-term conditions such as diabetes may reflect poor self-management. Patients with depression may have a feeling of hopelessness (which may influence feelings about treatment effectiveness), may be more likely to be socially isolated and lacking support and may struggle with limited concentration and energy. Sometimes, the management of one condition actively conflicts with the management of another. For example, treating a depressed patient might lead to a better mood but that might lead to a return of their appetite with potential negative effects on diet and diabetes care.

Equally important is the potential for the management of the long-term condition to have an impact on mood. Patients with long-term conditions are expected to monitor symptoms and make changes to their lifestyle, and many patients might find such activities to have a significant impact on their quality of life. Patients with multimorbidity have to deal with many self-management activities with only limited resources of energy, time, attention and motivation. This has led to calls for clinicians to think about not only the burden of disease in such patients but also the burden of treatment (see Chapter 8).

The organization of the healthcare system may contribute to the problem. Some aspects of the management of depression are better in patients with long-term conditions because the routine follow-up of patients with long-term conditions increases the opportunity to effectively manage depression, and single interventions can confer benefits for multiple disorders (e.g., exercise prescribed for the control of diabetes may impact favourably on mood).

However, the presence of mental and physical health multimorbidity can be problematic for a variety of reasons. The time-limited nature of primary care consultations means that decision-making is often centred around immediate patient concerns. Opportunities to offer patients an integrated approach to care, responding to physical and mental health problems are limited. Competing demands on health professional time often leads to priority being given to physical health problems. Those priorities are often reflected in patient behaviour as well.

It is possible that patients with comorbid depression and long-term conditions have difficulty in communicating effectively with practitioners. People with depression may not be active in seeking care at certain points in their lives, especially when symptoms are severe. In the presence of long-term conditions, both health professionals and patients normalize depression as a natural consequence of symptoms and loss of function. Even where health professionals are skilled at detecting depression, our case study (Box 9.1) highlights the difficulties in negotiating labels and treatment strategies with patients who may attribute symptoms of depression to other causes. Practitioners may avoid discussing self-management because they feel it might upset or annoy the patient.

A UK primary care study (Coventry et al. 2011; see Box 9.2) that examined barriers to depression care in multimorbidity found that recognition of depression is difficult. Depression can be misconstrued as part of ageing. If depressive symptoms appear periodically, there may be greater focus on physical problems.

In discussing mental health, patients with multimorbidity are acutely aware of the stigma associated with depressive illness, delaying help-seeking. In response to this, some have highlighted the benefits of using non-psychiatric language with patients with multimorbidity and how drawing on metaphors and figurative language can help patients to discuss their emotional health in less stigmatizing ways.

Management of long-term conditions – the chronic care model and collaborative care

The burden of long-term conditions and multimorbidity has led to important innovations in the delivery of care, such as the chronic care model (described in earlier chapters). In mental health, an

Box 9.2 Patient and professional experience of care

Difficulties in recognition

…at my age when I went through the change your emotions do change anyway, it’s all about getting older and accepting that you are getting older and…and I do think that plays a big part… (female patient, diabetes and depression)

…if I do go to see [the GP], it’s usually about something else and I don’t really think to say anything about it [the depression]…because it is not something that is happening continually…it is something that happens now and again and you just get low with it…to be honest I’ve not really told [the GP] you know. (female patient, diabetes and coronary heart disease and depression)

Reactions to screening questionnaires

…some patients just don’t like doing it [using the PHQ-9], but I think most people do, especially because I think it validates…their symptoms and also reinforces the fact that we are taking an interest in them. (GP with special interest in diabetes)

Stigma

…it’s the stigma that is attached to the psychology aspects of it. If you go and say you’re diabetic, then that is accepted and it’s easier to engage with…But when it comes to the issue of depression, then it’s a whole different ball game. If I’m feeling depressed, who do you talk to about it? (male patient, diabetes and coronary heart disease and depression)

Use of language

I mean in mental health you use quite a lot of metaphors because it’s an easier way of just explaining, because there’s no pictures, no scan, so I sort of use a metaphor, sort of like a kind of picture. (GP with special interest in mental health) (data from Coventry et al. 2011).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree