Monitoring and Auditing a Clinical Trial

Neurotic means he is not as sensible as I am, and psychotic means he’s even worse than my brother-in-law.

–Karl Menninger

The grand aim of all science is to cover the greatest number of empirical facts by logical deduction from the smallest number of hypotheses or axioms.

–Albert Einstein

MONITORING

For those who are unfamiliar with the detailed procedures of monitoring and auditing a clinical trial, the two processes may sound quite similar. In some ways, those processes are similar, but in most ways, they are significantly different. Auditing is a quality assurance function to provide information on how well monitoring is being done and the investigator (or other group audited) is performing.

The purpose of monitoring a clinical trial is to ascertain whether the trial is adhering to the protocol and progressing on schedule and, if not, why not and what can be done to modify or adjust the trial so that it gets back on schedule (or adheres to the protocol). While schedule primarily relates to the recruitment and enrollment of patients, it also relates to many other aspects of a trial. A few examples of additional concerns relate to issues or problems with drug supply, collecting data, entering data onto case report forms (CRFs; either paper, electronic, or both), and transmitting CRFs to the contract research organization (CRO) or sponsor or data management company. Other frequently encountered issues relate to collecting, storing, preparing, and sending biological samples (e.g., blood, urine, tissue biopsies) for analysis or sending paper, radiological, or other test results (e.g., electrocardiograms, magnetic resonance imaging scans, computed tomography scans) to experts (who serve as central readers) for their analysis and interpretation.

In addition, the monitor has the responsibility to ensure that all data are completely and correctly entered onto the CRFs and that all regulatory documents have been collected, signed, and filed appropriately according to both regulations and Good Clinical Practices (GCP). Finally, the monitor will discuss issues and status of the trial with the study coordinator, principal site investigator, and other study staff (e.g., pharmacist, nurses, drug inventory personnel)

In small companies, the person who monitors the sites may also be the person who is responsible for overseeing the planning of the trial, preparing the protocol and protocol-related documents (e.g., investigators’ brochure, operations manual, informed consent), and coordinating the data management. This person may also have the title of Project Leader or Project Manager. This section of the chapter will focus, however, on only the monitoring function that occurs at the site and on communications between the monitor and the site.

Who Is a Clinical Trial Monitor?

In most cases, the monitor is also called a Clinical Research Associate, but in some cases, the monitor is a physician or doctoral-level scientist at the company. Doctoral-level staff is more likely to be in charge of writing the protocol and performing a host of other functions in addition to monitoring activities at the site itself. An experienced MD or PhD will usually discuss more detailed medical-related issues with the site investigator than will a Clinical Research Associate, who is generally a bachelors- or masters-level professional.

How Frequently Is Monitoring Conducted?

While many monitoring activities can be done by telephone, fax, and e-mail, experience has shown that it is almost always required to conduct periodic monitoring visits to the site in person. The frequency of such visits generally ranges from once every four to every eight or 12 weeks, depending on the trial and its duration, issues, progress, and experience. Both the frequency of visits and the detail of monitoring must be tailored to the needs of the trial. This means that visits that occurred every four weeks at the start of a long-term trial are usually able to be stretched out to a longer interval between visits. Additional ad hoc visits are appropriate whenever there are problems at the site or major changes are made to the protocol.

In some cases, such as mega-trials of over 10,000 patients, monitoring becomes much less intensive than in traditional Phase 1 to 3 trials.

Remote Monitoring versus On-site Monitoring

Although there was a period a couple of decades ago when some believed that monitoring could be almost entirely conducted remotely by telephone, fax, and e-mail, this is no longer believed. It is an important principle that this approach to monitoring will almost certainly lead to many unpleasant surprises when the site is actually visited. To avoid being misled about a trial’s true status and to ensure the trial staff are conducting it according to the protocol, it is essential to conduct on-site monitoring visits on a periodic basis.

However, there are a few exceptions to the principle of conducting monitoring visits on-site. For example, Treatment INDs (Investigational New Drug Applications) have a large number of investigators, and it may not be possible to visit each site, and thus, almost all monitoring may have to be done by telephone, fax, and electronic means. This also applies to some Phase 4 active surveillance type trials. In each of these cases, only highenrolling sites may be monitored, or only a random selection of sites may be monitored. Controlled clinical trials (as opposed to surveillance-type trials) conducted during Phase 4, however, will require the same degree of intense monitoring that occurs in Phases 1 to 3.

Monitoring Activities that May Be Conducted In-house

While most of the critical monitoring activities occur at the investigator’s site, some activities are appropriate to conduct at the monitor’s office. These include:

Tracking regulatory document revisions

Writing trip reports

Writing follow-up letters based on the last monitoring visit

Providing the site with a list of queries to be addressed if they were not provided on-site

Reviewing the CRFs that are available

Tracking the drug supply and ordering additional drug or other supplies

Participating in project team meetings

Participating in periodic or ad hoc teleconferences with the site

Developing a newsletter for the sites

Monitoring the Rate of Enrollment

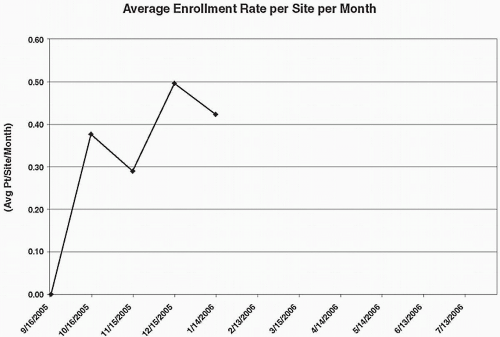

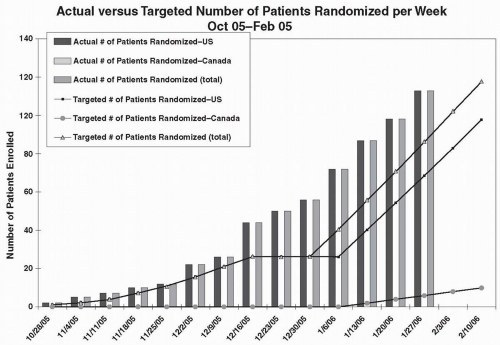

The primary approach to assessing the rate of trial enrollment is to assess the actual versus the targeted number of patients enrolled per site, and also to assess these numbers cumulatively for all sites in the study, on a per week or per month basis. A target number may be determined prior to initiating the trial, and, when the difference between the target number and actual number reaches a critical value (e.g., ten patients), additional recruitment efforts will be initiated. Figure 70.1 shows a trial that has met or exceeded the targeted numbers sought, but this happy event is not as common as one would hope. Variations of this graph are often prepared, such as that shown in Fig. 70.2.

Maintaining or Improving Site Morale as a Monitoring Goal

In addition to the specific checklist-oriented steps and procedures that a monitor uses on-site to ensure that he or she has reviewed each area and activity necessary, it is also important to help maintain and improve the morale and enthusiasm of the site staff and investigators. Trials that last a long time often hit a period where they are in the doldrums. Whether morale is stimulated by a trial newsletter or in other ways will depend on the people involved and the issues faced by the trial. The past practice of bringing pizzas or other food is disappearing, as is the practice of even bringing small snacks or soda drinks.

Monitoring of Academic-sponsored Trials

Although some investigators in academia do not have access to monitors who perform the functions mentioned in this chapter, it is becoming more common for them to have access to monitors from the Technology Transfer Office of their institution. However, they usually pay a fee from their National Institutes of Health, foundation, or other grant for this service. In some cases, they may have access to a nurse or another person on staff who fulfills this role and does not report to them. It is essential that the monitor be independent and not report to the site investigator and also that the monitor not serve as the study coordinator. Either of these situations would raise a serious conflict of interest. Having a trial adequately monitored is critically important to help ensure that appropriate standards are adhered to and that the trial is conducted properly.

Types of Monitoring Visits

The following are examples of the types of visits a monitor may conduct at a site.

Prestudy site visit. A monitor will typically conduct a prestudy site visit to meet the staff and investigator, discuss the trial, visit the facilities (e.g., pharmacy, storage facility, laboratories,

and treatment room), evaluate the capabilities of the site, and assess its ability to participate in the proposed trial.

Figure 70.1 Graph of actual number of patients enrolled in each of two countries versus the targeted numbers and also the cumulative totals.

Site initiation visit. A monitor will confirm that the required regulatory documents have been prepared and submitted to the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee and sponsor, and then actively review any procedures or other information related to the trial with the coordinator, investigator, and other relevant professionals (e.g., subinvestigators, pharmacists, specialists conducting magnetic resonance imaging scans, pathologists, radiologists, ophthalmologists, laboratory personnel). In some cases, this visit and the prestudy site visit may be combined.

Training the staff on-site. A monitor may do this at the same time as the site initiation visit or it may be done separately at an investigators’ meeting or at a separate visit to the site.

Regular study monitoring visit. Monitoring will be done by telephone, fax, and e-mail in addition to actual site visits. In the case of a Phase 1 trial, the monitor may stay at the site for up to a few weeks while the trial is underway or may make a few trips during this period. Otherwise, the first monitoring visit to the site may be triggered by enrollment of the first or first two subjects, and a schedule (e.g., every six weeks) will be established for follow-up visits.

End of study visit, also called a study closeout visit. After the trial is completed, the monitor will visit the site to arrange for its closeout. During this visit, the monitor will review all activities that will be conducted after the trial [e.g., answering all outstanding data queries, ensuring that all documents will meet Food and Drug Administration (FDA) auditing standards and that all drug is accounted for and extra drug is returned to the sponsor for destruction].

How a Monitor Is Trained

Most companies and CROs now have formal training courses to ensure that their monitors are well trained before they are sent to sites to conduct monitoring visits. The monitor’s training may be viewed as the following:

Classroom training. A number of short half- or one-day courses will be offered. There may be an initial one- or even two-week course for all new employees (e.g., on company policies, on

standard operating procedures, and an introductory course on drug discovery, development, and marketing), and it is likely to include some information (or a great deal) on monitoring. Self-testing and/or regular testing in class with formal examinations are an important part of assessing each individual’s progress.

Mock site visits. As part of an advanced course, there can be modules where the monitors-to-be are exposed to people playing roles of an investigator, study coordinator, and others to get them used to interacting with site staff and being proactive and assertive during a site visit. The number and intensity of such dress rehearsals will vary widely, and it is clearly critical for all monitors to become comfortable in such environments and interacting with a wide variety of personality types. An experienced trainer will record and grade the student’s performance, and the mock visit can be repeated as often as needed to ensure the student “passes” this part of their training.

Artificial telephone visits. This represents another type of training for the monitors, and the purpose is to help them be able to effectively interact with the sites by telephone (when necessary) to ensure they are able to represent the sponsor and to have issues discussed and have study staff do what they have been assigned to do both correctly and on time. A difficult problem or series of problems may be created for the student to address and hopefully resolve on the telephone with the purported study coordinator and/or site investigator.

Field training at sites. A monitor-in-training will often then be sent on one or more actual monitoring visits with an experienced monitor and possibly a trainer to observe the student, so that the student can learn from this experience. The monitor-in-training will usually be assigned one or more functions to perform so that their actions can be graded. Depending on their background, personality, and experience, some new monitors will not need many mock sessions or field trial visits before being able to be sent to sites on their own.

Observed visits at sites. The final step for the student monitor is to go to a site as a full-fledged monitor and to have an experienced monitor (or supervisor) attend to watch his or her performance. This part of the training allows for a smooth transition from step one (i.e., classroom training) to this final step. The student monitors will have to prepare and submit a regular monitor’s report for grading by their teachers. In many ways, this will also occur when they are working independently and submit copies of their reports to both the sponsor and investigator. In some cases, there may be additional activities/tests for the students to undertake before they are deemed qualified to have graduated from this training program. The many checklists and monitoring forms that sponsors (and CROs) prepare help the monitor as an aide-memoire both during training and while serving as a monitor.

Additional Training Issues

Other aspects and issues related to training for the company/ CRO include:

How to train the trainer. This may be done in-house or contracted to outside vendors.

How to train monitors about cultural differences and practices in conducting foreign monitoring visits

How to educate the monitors regarding the drug(s) they are dealing with, which will assist them in communicating and building a strong relationship with the site staff

How to conduct advanced training for those in unusual situations or with unusual staff issues. Using case studies is one possible mean of achieving this goal.

Whether to create special courses and offer advanced training in GCP, patient recruitment, patient retention, adverse events, and other important issues relating to the clinical trial, including drug design and protocol writing. Monitors will have many questions that need to be addressed throughout their career. These may be discussed with colleagues, supervisors, and regional or other heads of the monitors, as well as with in-house clinical staff in charge of the trial or a mentor that the monitor chooses.

Situations Where Both a Sponsor and Contract Research Organization Have Monitors

Many small pharmaceutical companies do not have their own monitors and rely on those of a CRO. In most cases, however, a sponsor that hires a CRO to provide monitoring and other services also has its own monitors. The sponsor has to decide whether it wishes its own monitors to conduct site visits alongside the monitor from the CRO. This can be done either on an ad hoc basis or for all monitoring visits. If the sponsor wishes to have this arrangement, it is discussed at the outset and arranged as an option in the contract between the sponsor and the CRO. Most CROs are comfortable with this type of arrangement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree