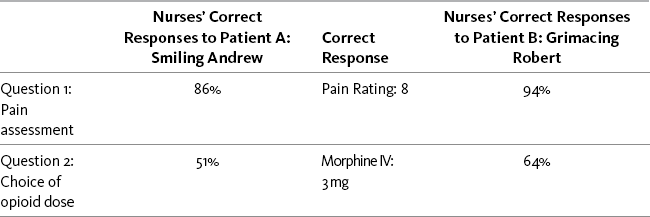

Chapter 2 Patient versus Caregivers/Family Health Care Conditions that Influence Clinicians’ Judgments of Pain Pain Threshold: Uniform versus Variable Pain Tolerance: High versus Low Behavioral and Physiologic Responses to Pain Acute Pain Model versus Adaptation Responses Clinicians Expect of Patients with Pain Patients’ Knowledge of Clinicians’ Expectations of Pain Behaviors Correction of the Misconceptions Concerning the Acute Pain Model Seeking Drugs versus Seeking Pain Relief Definitions Related to Addiction Likelihood of Occurrence of Addictive Disease Addiction as a Stigmatizing Label: Societal versus Medical Views Misconceptions about the Meaning of Positive Placebo Responses Misconceptions about Using Placebos for Pain Relief Recommendations against the Use of Placebos Debate about Use of Placebos in n-of-1 Trials Other Hidden Biases and Misconceptions Patient versus Caregivers/Family • “The clinician must accept the patient’s report of pain.” (APS, 2003, p. 1) • “Self-report should be the primary source of pain assessment when possible.” (APS, 2003, p. 33). • “…the patient’s self-report should be used as the foundation for the pain assessment.” (Miaskowski, Cleary, Burney, et al., 2005, p. 19) The Andrew-Robert survey presented in Box 1-1 (p. 18) illustrates what happens when clinicians do not adopt the patient’s self-report as the standard for assessment of pain intensity. This survey has been used by many nurse educators in hundreds of educational programs to explain the necessity of accepting the patient’s report of pain as the standard for assessment. The survey has become so familiar to staff nurse educators that it is often referred to simply as the Andrew-Robert survey. Several publications have reported the results of studies using this survey and modifications of it (McCaffery, Ferrell, 1991a, 1991b, 1992a, 1992b, 1994a, 1997a; McCaffery, Ferrell, O’Neil-Page, 1992). A summary of survey findings from 1990 to 2006 has been published by the originators of the survey (McCaffery, Pasero, Ferrell, 2007). The results of the Andrew-Robert survey as presented in Table 2-1 are based on the responses of 615 registered nurses who attended pain programs throughout the United States. The survey was administered to registered nurses before the pain conference began. In viewing the nurses’ responses to pain assessment (question 1), it is apparent that not all nurses understood that the patient’s self-report of pain is the single most reliable indicator of pain. Both of these patients reported their postoperative pain as 8, but 14% of the nurses did not record 8 for the smiling patient and 5% did not record 8 for the grimacing patient. Those nurses who did not record 8 falsified the record and made it impossible for the next nurse to evaluate previous treatment for pain. Table 2-1 Nurses’ Responses to the Survey: Assessment and Use of Analgesics* *Data collected in 2006; N = 615. As appears in Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 21, St. Louis, Mosby. Data from McCaffery, M., Pasero, C., & Ferrell, B. (2007). Nurses’ decisions about opioid dose. Am J Nurs, 107, 35-39. McCaffery M, Pasero C, Ferrell B. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. The Andrew-Robert survey is a quick and easy survey to use in small and large populations of nurses. The results of the survey help to generate discussion of common problems that arise in patient care. Another brief and more comprehensive survey of staff knowledge is titled Pain Knowledge and Attitude Survey and is available in Appendix A. When a patient reports pain, the health care professional’s responsibility is to accept and respect the report and to proceed with appropriate assessment and treatment based upon the self-report. All reports of pain are taken seriously. When difficulties arise in accepting the patient’s report of pain, some of the strategies listed in Box 2-1 may be helpful. An important distinction exists between believing the patient’s report of pain and accepting the report. Following the recommendations of the clinical practice guidelines does not require that the clinician agree 100% with what the patient says. Clinicians are not required to believe a patient but are required to accept what a patient says, convey acceptance to the patient, and take the appropriate action. Clinicians are entitled to their personal doubts and opinions, but they cannot be allowed to interfere with appropriate patient care. Box 2-1 summarizes some strategies that can be used when the patient’s report of pain is not accepted. Acute Pain Model versus Adaptation The APS addresses the misconceptions about the acute pain model by stating the following: • With regard to acute pain, the APS (2003) says, “Often but not always [italics ours], it is associated with objective physical signs of sympathetic branch autonomic nervous system activity, including tachycardia, hypertension. . . .” (p. 2). • With regard to persistent cancer pain, the APS (2003) says, “The lack of objective signs may prompt the inexperienced clinician to wrongly conclude the patient does not appear to be in pain” (p. 3). Nurses’ responses to the Andrew-Robert survey (see Table 2-1, p. 21) reveal that patients’ behavioral responses have significant effect on nurses’ pain assessments and treatment decisions (McCaffery, Pasero, Ferrell, 2007). The only difference between Andrew and Robert is their behavior—Andrew smiles and laughs with visitors, whereas Robert lies in bed and grimaces. This simple difference has a startling effect on nurses’ decisions about opioid doses. Similar findings also were reported regarding patients with low back pain. Decisions about lumbar surgery were not made on the basis of physical pathologic conditions but rather on behaviors demonstrated by patients during their evaluations (Waddell, Main, Morris, et al., 1984). As summarized by Turk and Okifuji (1997), “physicians appear to believe that behavioral demonstrations of pain, such as limping and grimacing, indicate something important about the nature of the patient’s pain and the need for prescribing specific treatments such as surgery and opioids” (p. 334). In another study of 755 patients, primarily in intensive care units, physiologic responses were monitored while the patients were undergoing tracheal suctioning (Arroyo-Novoa, Figueroa-Ramos, Puntillo, et al., 2007). Statistically significantly higher increases were noted in heart rate and systolic and diastolic BP, but these changes were not clinically significant. The authors suggest that methods of measuring these physiologic parameters may not be sensitive enough to capture the response to acute pain. For further discussion of the limited usefulness of physiologic measures in assessing pain, see the discussion of patients who are critically ill in Chapter 4, pp. 143-147. Thus, little research supports vital signs as being relevant indicators of pain, although they can be used as indicators of the need for further assessment of pain. A position statement by the ASPMN regarding assessment of pain in nonverbal patients (available at http://www.aspmn.org/Organization/documents/NonverbalJournalFINAL.pdf) suggests that physiologic indicators should not be used alone to assess pain but should be considered cues for further assessment of the possibility of pain (Herr, Coyne, Key, et al., 2006).

Misconceptions that Hamper Assessment and Treatment of Patients Who Report Pain

Subjectivity of Pain

Considerations When Doubts Arise

Behavioral and Physiologic Responses to Pain

Responses Clinicians Expect of Patients with Pain

Correction of the Misconceptions Concerning the Acute Pain Model

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree