Chapter 25 Miscellaneous supportive therapies for stress, ageing, cancer and debility

Cancer chemoprevention

Cancer chemoprevention can be defined as ‘the prevention of cancer in human populations by ingestion of chemical agents that prevent carcinogenesis’. It is also important to differentiate between cancer prevention (e.g. cessation of cigarette smoking) and cancer chemotherapy (the use of cytotoxic drugs after cancer diagnosis). Cancer chemoprevention has now developed into a well-defined discipline. Several recent epidemiological studies have demonstrated that dietary factors may reduce the incidence of cancers. In one study, involving 250,000 people, an inverse correlation was found between the incidence of lung cancer among people who smoke and consume carotene-rich foods. As well as carotenoids, there was a similar finding for vitamin C and oesophageal and stomach cancers; selenium and various cancers; and vitamin E and lung cancer. Epidemiological studies may help to find leads for chemopreventive agents, which can then be tested in laboratory experiments. Almost 600 ‘chemopreventive’ agents are known and they are usually classified as: inhibitors of carcinogen formation (ascorbic acid, tocopherols, phenols), inhibitors of initiation (phenols, flavones) and inhibitors of postinitiation events (β-carotene, retinoids, terpenes). Many are items of food or beverages (e.g. tea) and are sometimes called ‘functional foods’ or ‘nutraceuticals’. Those that are used purely as foods are not covered here, but some others can be found in the chapters for which they are most useful (e.g. ginger, Chapter 14; garlic, Chapter 15). Further examples are given in Table 25.1.

Table 25.1 Known types of chemopreventive agents

| Group | Examples |

|---|---|

| Micronutrients | Vitamins A, C and E, selenium, calcium, zinc |

| Food additives | Antioxidants |

| Non-nutritive molecules | Carotenoids, coumarins, indoles, alkaloids |

| Industrial reagents | Photographic developers, herbicides, UV-light protectors |

| Pharmaceuticals | Retinoids, antiprostaglandins, antithrombogenic agents, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs |

| Hormones and antihormones | Dehydroepiandrosterone, tamoxifen |

Chemopreventive agents may even work in synergy, with several components contributing to the overall effect, which may be the case with plant drugs. This approach has great promise, with both natural products and synthetics being potentially useful. Dietary campaigns by government bodies, the American Cancer Society and others recommend that 5–7 servings of vegetables be consumed daily to function as a source of cancer chemopreventive agents. However, it is not reasonable to assume that chemopreventive agents will safeguard humans from known carcinogenic risks such as smoking. As knowledge of these agents increases they will play an increasing role in cancer prevention. Chemoprevention will not be covered further, apart from tea, as it is a vast subject in its own right. However, there are some useful recent reviews which discuss compounds, mechanisms and future directions available, such as Shu et al (2010), Gullett et al (2010) and Cerella et al (2010). Some data on the chemopreventive effects of garlic, anthocyanins (bilberry) and others can be found in the monographs of these plants.

Tonics, stimulants, adaptogens and supportive therapies

Açai berry, euterpe oleracea mart. (euterpe fructus)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

This botanical drug has become very popular despite a lack of scientific evidence. Clinical data are lacking. The high content of polyphenols has been linked to a range of reported (mostly in vitro) antioxidant, antiinflammatory, antiproliferative and cardioprotective properties. Açai demonstrates promising potential with regard to antiproliferative activity and cardioprotection, but further studies are required (Heinrich et al In press).

Ashwagandha, withania somniferum (L.) dunal

Constituents

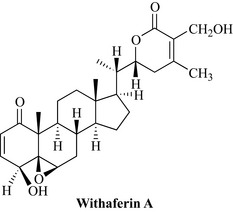

The root contains steroidal lactones (the withanolides A–Y), withaferin A (Fig. 25.1), withasomniferols A–C and others, phytosterols (such as the sitoindosides) and the alkaloids anahygrine, cuscohygrine, ashwagandhine, ashwagandhinine, withasomnine, withaninine, somniferine and others.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Extracts are antioxidant, immunomodulatory and sedative but, despite their wide usage, much of the clinical knowledge is still anecdotal. The few clinical trials which have been carried out are of doubtful quality and cannot be used to confirm efficacy, but they do show that the herb is generally safe. Many of the pharmacological effects have been substantiated in animal studies: for example, the adaptogenic and antistress activity was found to be comparable to that of ginseng, in mice and rats, and immunomodulatory activity has been confirmed. The extract has sedative activity and is reported to be anxiolytic, acting via the GABA-ergic system (Bhattarai et al 2010) and numerous other actions have been documented (for review, see Kulkarni and Dhir 2008). The usual dose of powdered root is 3–6 g daily. Side effects are rare but high doses can cause gastrointestinal irritation.

Centella, centella asiatica (L.) urban (centellae herba)

The herb has already been described in Chapter 22 (Skin). In addition to the wound healing effects, the plant is considered a ‘rasayana’ in Ayurvedic medicine; it enhances the immune system and is considered to have a rejuvenating, neurological ‘tonic’ and mild sedative effect. The immunomodulating effects of the herb have been shown in vitro and in vivo in mice. Studies in rats have shown that asiatic acid has some benefits on memory and learning (Nasir et al 2011), and that the extract can protect against certain types of neurodegeneration (Haleagrahara and Ponnusamy 2010), but in general, evidence for this use is lacking. A small double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial in healthy elderly volunteers in Thailand found that their health-related quality of life was improved and lower extremity strength increased after taking centella extract for 3 months (Mato et al 2009). It may be taken orally, often as an infusion, and applied topically. Other reported effects for the herb include anti-ulcer activity and spasmolytic effects. The powdered leaf is taken at an internal dose of 0.5–1 g daily, or the equivalent in the form of an extract.

Ginseng, panax ginseng C.A. meyer (panax radix), eleutherococcus senticosus (rupr. & maxim.) maxim. and related ‘ginseng’ species

Constituents

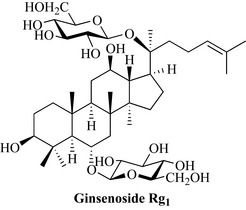

All types contain saponin glycosides (the ginsenosides Ra, Rb, Rg1, Rg2, Rs, etc.; Fig. 25.2). The ginsenosides are sometimes referred to as the panaxosides, but this nomenclature uses the suffixes A–F, which do not correspond to those of the ginsenosides. In Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus), the saponins (eleutherosides A–F) are chemically different, but have similar properties. Glycans (panaxans) also occur in P. ginseng. The actual composition of ginseng extracts depends upon the species and method of preparation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree