Minimally Invasive Distal Pancreatectomy

Paul D. Hansen

W. Cory Johnston

DEFINITION

Laparoscopic and robotic approaches to distal pancreatectomy were initially reserved for small, benign lesions of the pancreatic body and tail. As surgical expertise and refinements of the techniques progressed, indications have expanded to include larger lesions and invasive malignancies.

Minimally invasive resections are now commonly performed in cases of malignant neoplasms with oncologic outcomes equivalent to open resection in experienced hands.

The decision to attempt splenic preservation is dictated by the underlying pathology, the size and location of the lesion, and its relationship to the spleen and splenic vasculature.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

Cystic pancreatic lesions

Pancreatic metastases

Sequelae of chronic pancreatitis

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Tumors of the pancreatic body and tail are typically asymptomatic and are, therefore, more likely to manifest in the later stages of disease progression. Consequently, regional and distant disease is commonly encountered during the initial evaluation or at the time of surgical exploration.

Careful attention should be made in the history and physical examination to elicit symptoms and signs of advanced disease including back pain from invasion of the celiac plexus, nausea and early satiety from invasion or compression of the stomach or duodenum, and splenomegaly caused by thrombosis of the splenic vein.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

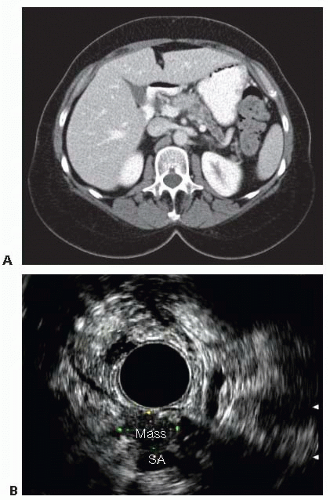

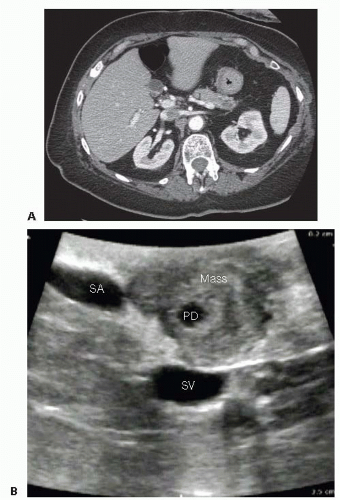

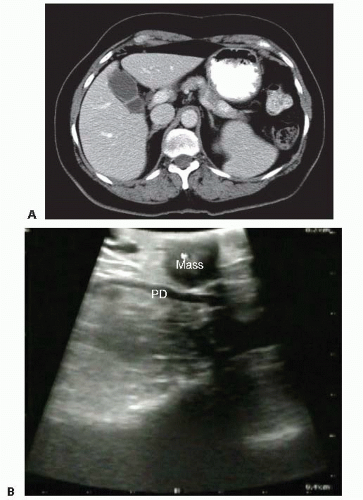

The primary imaging modality is pancreatic protocol, multiphase computed tomography (CT) scans including precontrast, arterial, and portal venous phases. 1- to 3-mm cuts with coronal and sagittal reconstructions allow a detailed analysis of the pancreas, the pathologic target, and the surrounding vasculature and viscera (FIGS 1, 2, 3A). Abdominal and pelvic CT is also useful in identifying the presence of lymphadenopathy, metastatic peritoneal or omental implants, and hepatic metastases. In patients with known or suspected pancreatic adenocarcinoma, a staging chest CT is also recommended.

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is slightly more sensitive in identifying liver metastases but provides less anatomic soft tissue detail regarding the pancreas and vasculature. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can be helpful in grossly examining ductal anatomy but does not provide fine detail. MRI requires a higher degree of patient cooperation but may be helpful in patients with contrast allergies or other contraindication to contrastenhanced CT.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is operator-dependent but can result in a more accurate assessment of tumor size and relationship to the portal and superior mesenteric veins (SMV) (FIG 1B). Assessment of superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and celiac involvement is no better than CT. Tissue sampling via ultrasound-directed fine needle aspiration (FNA) of primary tumor or regional lymph nodes may provide confirmatory tissue diagnosis. EUS-guided sampling of fluid from pancreatic cystic lesions may help distinguish between benign and premalignant tumors.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can be useful in providing fine details of pancreatic and bile duct anatomy, such as dilatation, strictures, luminal defects, or masses.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Feasibility of resection should be determined preoperatively based on cross-sectional imaging and EUS. We use National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for resectability based on the tumor’s relationship to the SMA and celiac trunk.1 Portal, superior mesenteric, splenic, and left renal vein involvement do not preclude resection but may suggest a role for neoadjuvant therapy.2 Resection of the celiac trunk with reconstruction of the hepatic artery has been described in numerous series, but most major American centers have not adopted this approach.3

The extent of gland resection is variable and should be directed by tumor location within the pancreas and its relationship with relevant blood vessels. Lesions in the tail of the pancreas can be resected with preservation of the neck and body, whereas more proximal lesions may require division of the gland closer to the portal vein. The gastroduodenal artery (GDA) is generally considered the landmark for the proximal limit of transection, as division of the pancreas more proximally places the intrapancreatic bile duct at risk of injury.

The decision to include the spleen in the resection is typically made preoperatively based on surgeon preference and the characteristics of the tumor. If malignancy is suspected, the spleen and lymphatic tissue along the splenic vessels should be resected en bloc with the pancreas. Cystic lesions that are considered low risk for malignancy can be considered for a spleen-preserving approach. Intraoperative findings may alter plans for spleen preservation.

Central venous access is typically not necessary as long as reliable, large-bore peripheral intravenous (IV) lines are established. An arterial blood pressure catheter can be placed at the discretion of the anesthesiologist.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine or, in some cases, in a gentle right semilateral decubitus position on a padded mattress.

The arms are supported on arm boards at just under 90 degrees to prevent stretch of the brachial plexus. Alternatively, the arms may be tucked at the patient’s side to facilitate placement of fixed retractors.

During the dissection, the operating table is positioned in reverse Trendelenburg with the left side slightly elevated so that the hollow viscera fall caudad and to the right, away from the operative field.

The position of the operating surgeon depends on the position of the tumor within the pancreas and may change during the procedure. During mobilization of the stomach and colon, the surgeon is typically on the patient’s right with the assistant on the patient’s left. Once the body and tail of the pancreas are exposed, the surgeon’s position depends on tumor location. If the tumor is distal and the transection of the pancreas will be in the body, the surgeon stays on the patient’s right. If the tumor is in the proximal body and the point of transection will be at the pancreatic neck, the dissection may be easier by having the surgeon stand on the patient’s left. This facilitates the surgeon’s ability to dissect along the superior mesenteric and portal veins and create the window behind the neck of the pancreas.

We typically use a 10-mm high-definition (HD) laparoscope to ensure optimal visualization. Alternatively, a 5-mm HD laparoscope may be used.

We prefer to use dual carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation devices. This can be valuable in cases where bleeding occurs, as laparoscopic suction devices can rapidly decompress pneumoperitoneum.

TECHNIQUES

DIAGNOSTIC LAPAROSCOPY

Port Placement

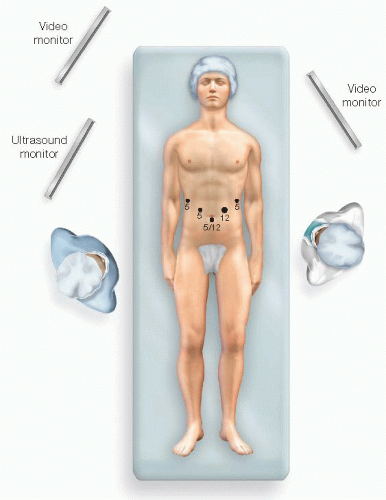

For exploratory laparoscopy, we start with two ports. The first is typically 11 or 12 mm and placed just below the umbilicus. The second is an 11 or 12 mm and placed just lateral to the left rectus muscle, at the level of the umbilicus. These ports facilitate peritoneoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasound examination.

Two or three additional ports are placed, depending on the complexity of the procedure and on the position of the tumor within the pancreas (FIG 4).

A high, right 5-mm subcostal port will ultimately serve to retract the stomach cephalad to expose the pancreas. Additional 5-mm ports may be placed just lateral to the right rectus muscle above the level of the umbilicus or laterally along the left subcostal margin. Which ports are used for the camera, surgical dissection, or assistant’s retraction will depend on the position of the tumor as described earlier.

A hand port may be used at the surgeon’s discretion. Hand assistance can be very useful for large tumors that invade the surrounding viscera, inflammatory masses, and proximal tumors that abut the celiac axis. The optimal position of the port is variable. Right-handed surgeons will prefer to have the left hand in the port, and a lower midline position is preferred. Left-handed surgeons typically prefer to have their right hand in the port, which should be positioned laterally beneath the left costal margin.

Examination of Peritoneum and Viscera

The entire peritoneal surface is examined for carcinomatosis. Suspicious lesions are biopsied and sent for immediate pathologic analysis.

The abdominal viscera are likewise examined and any suspicious lesions are sampled. Although we look at the omentum and easily accessible viscera, we typically do not “run the bowel” unless otherwise indicated.

The root of the small bowel mesentery and the undersurface of the transverse mesentery are examined in cases of large malignant tumors and those located in the central pancreas.

Ascitic fluid is sent for cytology.

Intraoperative Ultrasound

The liver is systematically examined for evidence of metastases. Surface lesions are wedged out with a small margin and sent for frozen section analysis. Intraparenchymal nodules are biopsied with a coring needle and sent for immediate pathologic analysis.

The pancreatic parenchyma is examined. The exact location and dimensions of the tumor are determined as well as its relationship to the duct (FIG 3B).

The relationship of the tumor to the SMA, SMV, splenic vessels, and left renal vein is determined (FIG 2B). The intended location of pancreatic gland transection is estimated.

Paraaortic lymph nodes as well as those along the origins of the celiac trunk and the SMA are examined. Suspicious lymph nodes outside the limitations of the proposed resection should be biopsied and sent for frozen section.

The procedure is terminated or a predetermined palliative bypass is performed if diagnostic laparoscopy reveals metastatic or locally unresectable disease.

LAPAROSCOPIC DISTAL PANCREATECTOMY AND SPLENECTOMY

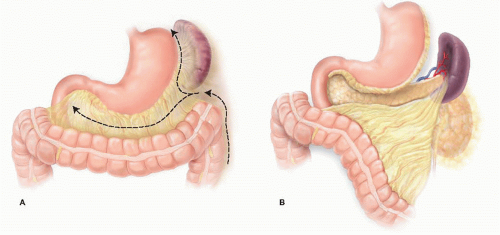

Mobilization of the Splenic Flexure

With the patient in reverse Trendelenburg position with the left side rotated up, the lateral peritoneal reflection is incised and the proximal descending colon is medialized. The distal transverse colon and splenic flexure are brought down away from the inferior splenic pole. This dissection occurs in the avascular plane between Gerota’s fascia and the mesocolon.

The inferior pole of the spleen is mobilized by dividing the avascular retroperitoneal attachments.

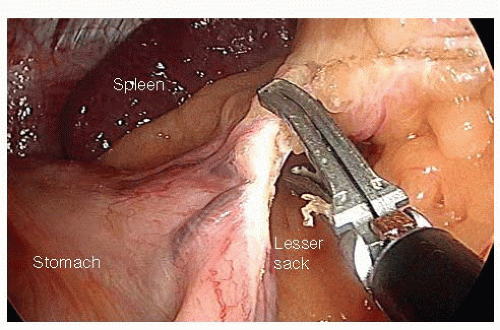

Entry into the Lesser Sack and Division of the Short Gastric Vessels

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree