Overview

Mental health problems are common. At any time, around one in six working age individuals will suffer from symptoms suggestive of a psychiatric disorder. Mental ill health is now the leading cause of sickness absence and long-term work incapacity in most developed countries

Mental health problems can have a significant impact on work performance

Asking about symptoms of common mental health problems and considering risk should be part of routine clinical practice. Mental health problems often occur together with physical health problems and therefore may not be immediately obvious

There are effective, evidence based treatments for psychiatric disorders. Most individuals who suffer from mental illness should be able to remain in the workforce

An adverse psychosocial work environment may act as a risk factor for mental illness, but ‘work stress’ is not a diagnosis. Being in work has many beneficial effects on mental health

Introduction

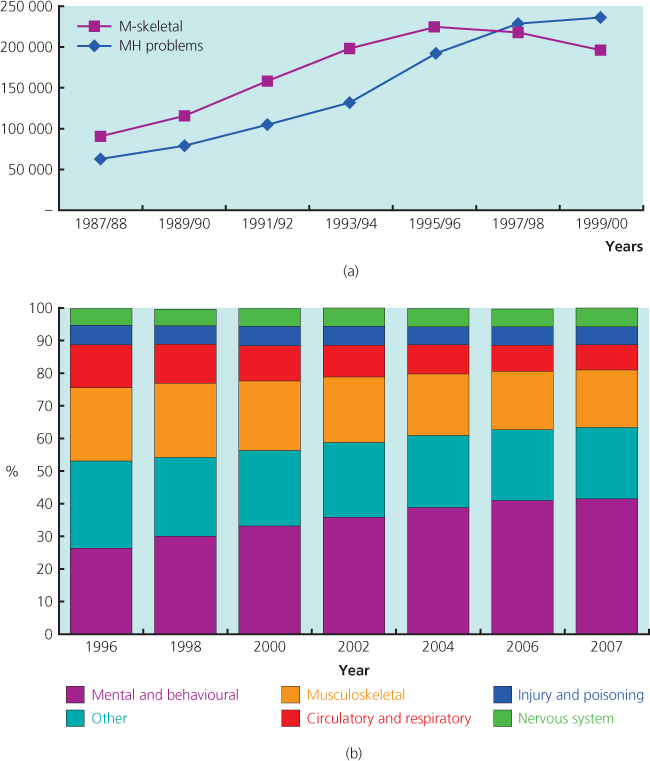

Until recently, the most common reasons for sickness absence and disability pensions were musculoskeletal disorders such as back pain and shoulder complaints. However, over the last few decades, the clinical problems faced by occupational health practitioners, GPs and doctors assessing insurance and benefit claims have changed, with mental health problems now being the leading cause of work incapacity. This change is demonstrated in Figure 9.1a. As shown in Figure 9.1b, the trend toward a greater amount of work incapacity being attributed to mental illness has continued, although in recent years this has been in part due to lower numbers of claims for other conditions, with no change in the overall numbers claiming incapacity benefits. Psychiatric disorders now account for around 40% of the total time covered by sickness certification. Within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries (comprising much of Europe, the United States, Canada, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and Korea) mental ill health is listed as the primary reason for around 35% of all disability benefits.

Figure 9.1 (a) The numbers of incapacity benefits in England and Wales throughout the late 1980s and 1990s, demonstrating an apparent change in the ‘cause’ of occupational incapacity. Source 1% sample of all Incapacity Benefit claims. Similar changes were observed in most developed countries around the same period. (b) Percentage of incapacity benefits in England and Wales by primary condition from 1996 to 2007. MH, mental health; M-skeletal, musculoskeletal problems.

There is also increasing recognition that psychiatric disorders can adversely affect work aside from sickness absence. Presenteeism refers to the situation where an individual is unwell, yet remains at work and is less productive as a result of their illness. Presenteeism can be difficult to measure, but the Sainsbury’s Centre for Mental Health calculated that the costs arising from mental health-related presenteeism are around double those of sickness absence. For a variety or reasons, such as stigma, delayed treatment and the specific symptom profile, presenteeeism appears to be particularly prominent in psychiatric disorders.

As a result of the increasing social and economic consequences of psychiatric disorders, both policy-makers and professional bodies involved in occupational health have become increasingly interested in mental health. However, the relationship between mental health and work is complicated. In the UK, the United States and many European countries, there is a growing awareness that good health, both physical and mental, is unevenly distributed in society. Those at the bottom of society have worse health and are more likely to be workless or have poor-quality employment. In this context mental ill health can be regarded as both an exposure and an outcome. Poor mental health, whether alone or in combination with physical ill health makes sustained employment difficult. In addition, worklessness or adverse working conditions can contribute to the onset and maintenance of mental ill health.

Epidemiology

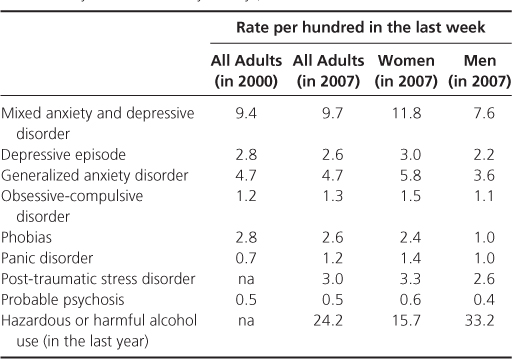

In the UK the Office for National Statistics has carried out surveys of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the general population using objective assessment tools in 1993, 2000 and 2007. The prevalence of all psychiatric disorders has stayed largely static during this time, with around one in six of the working age population meeting diagnostic criteria for a common mental disorder at all time points. The prevalence of more severe mental disorders, such as psychosis was much lower, at around 0.5%. The prevalence estimates for a range of psychiatric disorders obtained using highly structured interviews in community surveys are shown in Table 9.1. As demonstrated in this table, females are at increased risk of depression and most anxiety disorders, although men are more likely to use harmful amounts of alcohol.

Table 9.1 The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in one week of 2000 and 2007 based on a community sample of adults living in England (data from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Surveys)

Despite the prevalence of psychiatric disorder being relatively stable in the population, the extent to which psychiatric disorders are associated with occupational dysfunction has changed dramatically. The proportion of the UK working age population on long-term benefits has doubled in the last 25 years. Two discrete contributors to this change can be identified. First, a greater proportion of those beginning a claim list psychiatric disorder as their primary illness. As discussed later in this chapter, there are a number of potential reasons for this. Second, those with psychiatric disorder are less likely to leave the pool of benefits recipients than sufferers from other disorders. It has been suggested that this must relate to the configuration of services established to treat psychiatric disorders, especially as effective evidence-based treatments are available for the common mental disorders which affect the vast majority of this group.

How are Psychiatric Disorders Classified?

Common Mental Disorders

The term ‘common mental disorders’ does not have a formal definition, but is generally taken to include depression and anxiety disorders. Common mental disorders have a major impact on occupational function and are the biggest single cause of working days lost in most developed countries. Although symptoms typical of common mental disorders may not be as dramatic as those associated with other types of psychiatric disorder, they can be particularly damaging to an individual’s ability to work. As a result, the World Health Organization predicts depression will be the leading cause of disability across the developed world by 2020. Within the UK the overall cost of depression is estimated to be more than £9 billion per year.

Depression does not refer to ‘normal’ or understandable sadness but a psychiatric syndrome consisting of a broad but well-recognized constellation of symptoms. The key features of a depressive episode are shown in Box 9.1. Symptoms must be present for 2 or more weeks and have resulted in significant social or occupational impairment.

Core features

- Depressed mood

- Loss of interest in usual activities

- Fatigue or decreased energy

Other common symptoms

- Difficulty concentrating

- Reduced self-esteem

- Guilt

- Pessimistic view about the future

- Ideas of self harm or suicide

- Disturbed sleep (insomnia or hypersomnia)

- Appetite and weight change (in either direction)

- Agitation or retardation

- Loss of libido

Anxiety is a symptom rather than a diagnosis and can be part of a number of psychiatric disorders. ‘Anxiety disorders’ is an umbrella term to describe a group of conditions in which anxiety is the predominant symptom. These include generalized anxiety disorder, phobias, obsessive compulsive disorders and panic disorder. Aside from simple phobias, generalized anxiety disorder is the most common anxiety disorder with a prevalence of approximately 5%, although often underdiagnosed. Sufferers report a persistent level of ‘background’ or ‘free-floating’ anxiety, present almost all the time. Frequently, they report not knowing why they feel anxious. This presents as worry or tension, often in association with physical symptoms of anxiety such as a dry mouth, ‘butterflies’, palpitations or sweats. Further symptoms include poor sleep, ‘tension’ headache and irritability. Within a work setting, anxiety may present as recurrent short episodes of sickness absence, avoidance of responsibility or certain meetings or a loss of productivity. Anxiety can also be a particular problem when a worker tries to return to work after a prolonged period away, regardless of the original cause of the absence.

Severe Mental Illness

The term ‘severe mental illness’ is usually used to describe those suffering from schizophrenia, other forms of psychosis or bipolar disorder. Typically these emerge in late adolescence or early adult life and often run a chronic, fluctuating course.

Schizophrenia is a syndrome comprising a number of disturbances of thought, affect, and behaviour. ‘Positive’ symptoms include abnormal experiences such as thought insertion or withdrawal, delusions (beliefs, firmly held against evidence to the contrary, which are out of keeping with the person’s social and cultural background) and hallucinations (perceptions in the absence of stimuli). Often delusions will be unpleasant and persecutory in nature. Auditory hallucinations are the most common in schizophrenia, although hallucinations in other modalities can occur. Positive symptoms respond well to medication, but ‘negative’ symptoms, such as apathy and social withdrawal, can be more refractory. At times, delusional ideas can focus on the workplace and a psychotic illness may present as ideas about co-workers or entire organizations persecuting an individual. Reports of bullying or harassment are relatively common, but persecutory delusions will differ from such complaints as they are often more bizarre in their nature and will be held with absolute conviction regardless of evidence to the contrary.

Although it used to be thought that the prevalence of schizophrenia is similar among different cultures and countries, it has now been shown that there is wide variation in prevalence between countries, and that that schizophrenia is significantly more common in urban environments and among migrant populations. Occupational outcomes vary somewhat, but across Europe less than 10% of patients with schizophrenia are able to support themselves through work without the need for benefits.

Bipolar disorder is characterized by repeated episodes of disturbed mood. At least one of these episodes must involve elevated mood—mania or hypomania. The differences between mania and hypomania are not well defined and differ between European and American classification systems, but broadly mania is more severe, and often includes psychotic symptoms. Changes in biological function are common to both and include increased energy levels, reduced need for sleep, reduced appetite and increased libido. Attention and concentration are often reduced as the individual copes with an increased volume and speed of thoughts. Although a manic worker may feel they are being very productive and may have grandiose ideas regarding their role in an organization, the reality is that any work produced in a manic or hypomanic state is often disorganized and of poor quality.

The depression of bipolar disorder resembles that of the more common unipolar depression, although some bipolar patients describe increased appetite and increased sleepiness in their depressed phase. While not yet part of all formal classifications systems there is increasing recognition of a subset of patients who may have had only a short-lived or relatively minor episode of mood elevation but whose clinical picture is dominated by recurrent episodes of depression. So called bipolar II patients are important to identify as standard antidepressant medication is often either unhelpful or can worsen symptoms. Alternative treatment strategies are being developed. The prevalence of bipolar disorder is around 1%. Although a return to normal pre-morbid levels of function is much more common in bipolar disorder than other types of severe mental illness, only around 50% of individuals with bipolar disorder are in any form of work. Despite such figures, there are many examples of individuals with bipolar disorder having very successful work careers.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a rare psychiatric condition but nonetheless is often discussed within the context of occupational psychiatry. As a discrete condition, it has had a controversial history, and the rise in the number of people being diagnosed has led even some of those who first described the condition to call for a rethink of the diagnostic criteria. Unlike other psychiatric disorders, which are recognized to be multifactorial in origin, the diagnostic criteria for PTSD state that it follows exposure to a stressful event of an exceptionally threatening or catastrophic nature which is likely to cause distress in almost anyone. There are three domains of symptoms.

- The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced, for example as flashbacks or intrusive dreams or thoughts.

- There is persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, including an inability to recall some aspects of the trauma and a feeling of detachment from others.

- There is evidence of persistently increased arousal such as hypervigilance or difficulty in falling asleep.

These symptoms must last at least a month, cause significant impairment in social or occupational function and strictly need to emerge within 6 months of the traumatic incident. Community studies have shown over 40% of adults report suffering from a major trauma at some point in their life. Although a diagnosis of PTSD should be considered in someone who has suffered a traumatic event, it should be remembered that the majority of those exposed to such events have only transient distress and that other conditions such as depression are a more common response to trauma than PTSD. Many employers are keen to implement debriefing interventions following a potentially traumatic event in the workplace; however, this should be advised against as a number of systematic reviews have shown that such strategies are not of benefit and may even increase the risk of PTSD.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is sometimes seen in the working population, but often undiagnosed. At its mildest, it can be difficult to distinguish from aspects of normal personality, and this is further complicated by around a third of cases beginning in childhood. Obsessions are intrusive and unwelcome thoughts which can be about a variety of topics, for example contamination or safety. These are not just excessive worries about real-life problems but much more disabling concerns which the individual recognizes are not based in reality. Compulsions are behaviours carried out in an attempt to alleviate the distress caused by the obsessions. Hence where the obsessive thought relates to issues of contamination, the compulsive act of handwashing is designed to reduce the distress of this thought. As with all psychiatric disorders the diagnosis requires there to be significant social or occupational impairment. Patients with OCD often take up huge amounts of time in completing their compulsive acts to the point where their anxiety is sufficiently reduced. Such symptoms can make a worker appear to be slow or avoidant of certain tasks.

Cognitive Impairment

With an ageing workforce, cognitive function is becoming an increasingly important issue. Cognitive function incorporates a number of domains; attention, language, constructional skills, memory, executive function and others. Dementia is a common cause of cognitive impairment but is by no means the only one. Depression and anxiety are often associated with impaired attention which can in turn present with memory problems. A number of physical disorders (e.g. epilepsy) can also impact on aspects of cognitive function as can both prescribed and non-prescribed drugs. The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease in which memory impairment and confusion are often early signs. In other forms of dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia, personality change and apathy are more prominent. The most obvious occupational impact of cognitive impairment will be impaired work performance, although this is often recognized relatively late due to the very gradual onset of symptoms and ability of previously highly functioning individuals to hide any emerging difficulties.

Alcohol and Drug Problems

Alcohol problems are widespread in the UK and other developed countries and have a significant impact on both individuals and employers. In England around 250 000 people come to work each day with a hangover. Alcohol is implicated in 20% of all accidents and half of all fatal accidents in the workplace. Up to 15% of days off sick are associated with alcohol. Illicit drug use is also common in most developed countries, with 1 in 10 adults in England and Wales admitting to using drugs at least once in the previous year.

Hazardous drinking describes a pattern where an individual regularly drinks more than the recommended limits (2–3 units per day for women and 3–4 units per day for men). Harmful drinking is hazardous drinking where there is evidence of harmful consequences for the individual. Well-validated tools such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Questionnaire are available to assist health professionals to identify alcohol problems in their patients. Alcohol dependence syndrome consists of a number of symptoms (Box 9.2). It is estimated up to 5% of the workforce in the UK are alcohol dependent.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree