KEY CONCEPTS

![]() Unrecognized pregnancy is the most common cause of amenorrhea. A urine pregnancy test should be one of the first steps in evaluating this disorder.

Unrecognized pregnancy is the most common cause of amenorrhea. A urine pregnancy test should be one of the first steps in evaluating this disorder.

![]() For hypoestrogenic conditions associated with primary and secondary amenorrhea, estrogen (with a progestin) is provided.

For hypoestrogenic conditions associated with primary and secondary amenorrhea, estrogen (with a progestin) is provided.

![]() Causes of menorrhagia are either systemic disorders or specific uterine abnormalities.

Causes of menorrhagia are either systemic disorders or specific uterine abnormalities.

![]() Pregnancy, including intrauterine pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and miscarriage, must be at the top of the differential diagnosis for any woman presenting with heavy menses.

Pregnancy, including intrauterine pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and miscarriage, must be at the top of the differential diagnosis for any woman presenting with heavy menses.

![]() The reduction in menorrhagia-related blood loss with use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and oral contraceptives is directly proportional to the amount of pretreatment blood loss.

The reduction in menorrhagia-related blood loss with use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and oral contraceptives is directly proportional to the amount of pretreatment blood loss.

![]() Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are considered therapeutic options in a variety of menstruation-related disorders. Guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists indicate that both nulliparous and multiparous women at low risk of sexually transmitted diseases are good candidates for IUD use.

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are considered therapeutic options in a variety of menstruation-related disorders. Guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists indicate that both nulliparous and multiparous women at low risk of sexually transmitted diseases are good candidates for IUD use.

![]() Anovulatory bleeding is the standard terminology used to describe bleeding from the uterine endometrium as a result of a dysfunctioning menstrual system, specifically excluding an anatomic lesion of the uterus.

Anovulatory bleeding is the standard terminology used to describe bleeding from the uterine endometrium as a result of a dysfunctioning menstrual system, specifically excluding an anatomic lesion of the uterus.

![]() Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) can present as a variety of menstruation disorders, including amenorrhea, menorrhagia, and anovulatory bleeding. Although its definition continues to evolve, it is generally considered a disorder of androgen excess that often includes polycystic ovarian morphology and ovulatory dysfunction.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) can present as a variety of menstruation disorders, including amenorrhea, menorrhagia, and anovulatory bleeding. Although its definition continues to evolve, it is generally considered a disorder of androgen excess that often includes polycystic ovarian morphology and ovulatory dysfunction.

![]() Metformin and thiazolidinedione use for anovulatory bleeding associated with PCOS is beneficial not only for anovulatory bleeding and fertility but also for improving glucose tolerance and other metabolic parameters that contribute to cardiovascular risk.

Metformin and thiazolidinedione use for anovulatory bleeding associated with PCOS is beneficial not only for anovulatory bleeding and fertility but also for improving glucose tolerance and other metabolic parameters that contribute to cardiovascular risk.

![]() The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are first-line pharmacologic treatment options for premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are first-line pharmacologic treatment options for premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

Problems related to the menstrual cycle are exceedingly common in women of reproductive age. This chapter discusses the most frequently encountered menstruation-related difficulties: amenorrhea, menorrhagia, anovulatory bleeding (including polycystic ovary syndrome, PCOS), dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). The need for effective treatments of these disorders stems from their negative impact on any or all of the following: quality of life, reproductive health, and long-term detrimental health effects, such as increased risk of osteoporosis with amenorrhea and cardiovascular disease with PCOS.

AMENORRHEA

Amenorrhea is described as either primary or secondary in nature. Primary amenorrhea is the absence of menses by age 16 years in the presence of normal secondary sexual development or the absence of menses by age 14 in the absence of normal secondary sexual development. Secondary amenorrhea is the absence of menses for three cycles or for 6 months in a previously menstruating woman. There is a significant amount of overlap between the two. The initial evaluation of amenorrhea often is the same, regardless of age of onset, except in unusual clinical situations.1

Epidemiology

Primary amenorrhea occurs in less than 0.1% of the general population. Secondary amenorrhea, in comparison, has an incidence of 0.7% to 5% in the general population and occurs more frequently in women younger than 25 years with a history of menstrual irregularities and in those involved in competitive athletics.2

Etiology

![]() Unrecognized pregnancy is the most common cause of amenorrhea. A urine pregnancy test should be one of the first steps in evaluating this disorder. In organizing an approach to diagnosis and treatment, it is helpful to consider the organs involved in the menstrual cycle, which include the uterus, ovaries, anterior pituitary, and hypothalamus.

Unrecognized pregnancy is the most common cause of amenorrhea. A urine pregnancy test should be one of the first steps in evaluating this disorder. In organizing an approach to diagnosis and treatment, it is helpful to consider the organs involved in the menstrual cycle, which include the uterus, ovaries, anterior pituitary, and hypothalamus.

After excluding pregnancy, the most common causes of secondary amenorrhea are hypothalamic suppression, chronic anovulation, hyperprolactinemia, ovarian failure, and uterine disorders.3

Pathophysiology

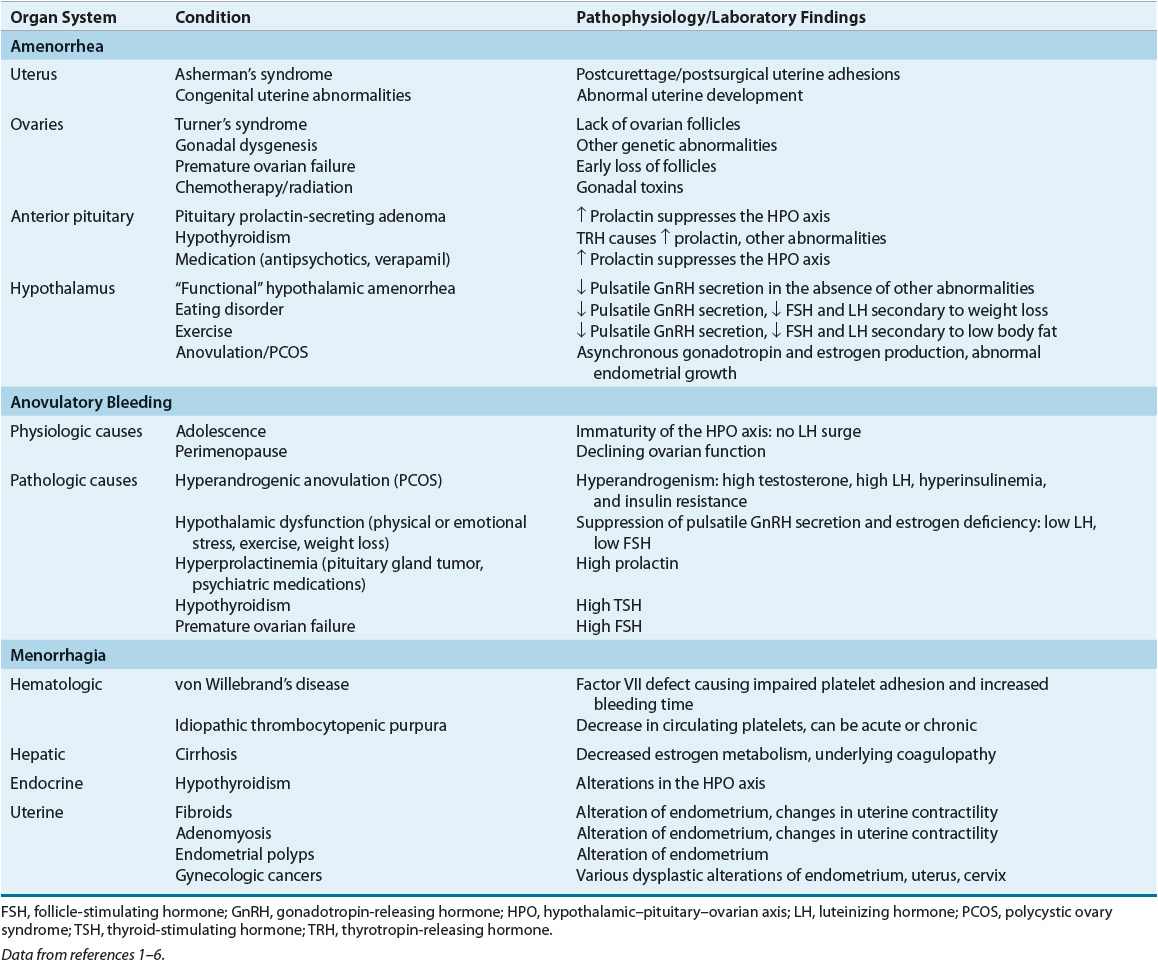

Each organ in the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian–uterine axis is of importance in determining amenorrhea’s etiology and pathophysiology. Beginning with the uterus/outflow tract and progressing caudally will result in a comprehensive differential diagnosis. Table 63-1 lists the pathophysiology of amenorrhea relative to the organ system(s) involved and the specific condition(s) that results in amenorrhea.

TABLE 63-1 Pathophysiology of Selected Menstrual Bleeding Disorders

Uterus/Outflow Tract

For menstruation to occur, a uterus, functional endometrium, and patent vagina must be present. Several anatomic abnormalities may cause amenorrhea. If primary amenorrhea is the presenting symptom, a congenital anomaly such as imperforate hymen or uterine agenesis may be present and often discovered by physical examination. An acquired condition of the genital tract, such as Asherman’s syndrome or cervical stenosis, is more likely in secondary amenorrhea.

Ovaries

Normal ovarian function is critical for menstruation to occur. The ovaries must respond appropriately to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) by secreting estrogen and progesterone in proper sequence to influence endometrial growth and shedding (Fig. 63-1).

FIGURE 63-1 Hormonal fluctuations with the normal menstrual cycle. (FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.)

(Courtesy of Hatcher RA, Nelson AL, Zieman M, et al. A Pocket Guide to Managing Contraception. Tiger GA: Bridging the Gap Foundation, 2003;1–146.)

Premature ovarian failure occurs when no viable follicles remain in the ovaries. This is because estrogen production is insufficient to stimulate endometrial growth in the absence of follicles. In a woman younger than 30 years, amenorrhea due to premature ovarian failure may be the result of genetic anomalies.1

The ovaries may play a role in amenorrhea through anovulation. Ovulation is required for the follicle (an estrogen-secreting body) to become a corpus luteum (a progesterone-secreting body). Without ovulation, the proper sequence of estrogen production, progesterone production, and estrogen/progesterone withdrawal will not occur. This can result in amenorrhea. Anovulation can occur secondary to thyroid disease, androgen excess (as in PCOS), or chronic illness.

Pituitary Gland

The anterior pituitary gland secretes FSH and LH in sequential fashion in response to hypothalamic stimulation and a complex ovarian feedback mechanism. Normal secretion of FSH and LH is altered by several endocrinologic and iatrogenic conditions, including thyroid disease, hyperprolactinemia, and dopaminergic drug administration.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus secretes cyclic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which causes the pituitary to produce FSH and LH. Disrupting this cyclic process will interrupt the hormonal cascade that results in normal menstruation. Anorexia nervosa, bulimia, intense exercise, and stress may cause hypothalamic amenorrhea.

TREATMENT

The treatment options for amenorrhea are as varied as its causes.

Desired Outcome

Therapeutic modalities for amenorrhea should ensure the occurrence of normal puberty and restore the menstrual cycle. Treatment goals include bone density preservation, bone loss prevention, and ovulation restoration, improving fertility as desired. Amenorrhea from hypoestrogenism may affect quality of life via hot flash induction (premature ovarian failure), dyspareunia, and, in prepubertal females, lack of secondary sexual characteristics and absence of menarche. Treatment is targeted at reversing these effects.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION Amenorrhea

General Approach to Treatment

The overall success of any intervention to treat amenorrhea depends on proper identification of the disorder’s underlying cause(s). Once the cause is identified, the appropriate intervention(s) can be made. For patients experiencing amenorrhea secondary to hypoestrogenic states, a diet rich in calcium and vitamin D is essential to minimize negative impact on bone health.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Nonpharmacologic therapy for amenorrhea varies depending upon the underlying cause. Amenorrhea secondary to anorexia may respond to weight gain. In young women for whom excessive exercise is an underlying cause, reduction of exercise quantity and intensity are important.

Pharmacologic Therapy

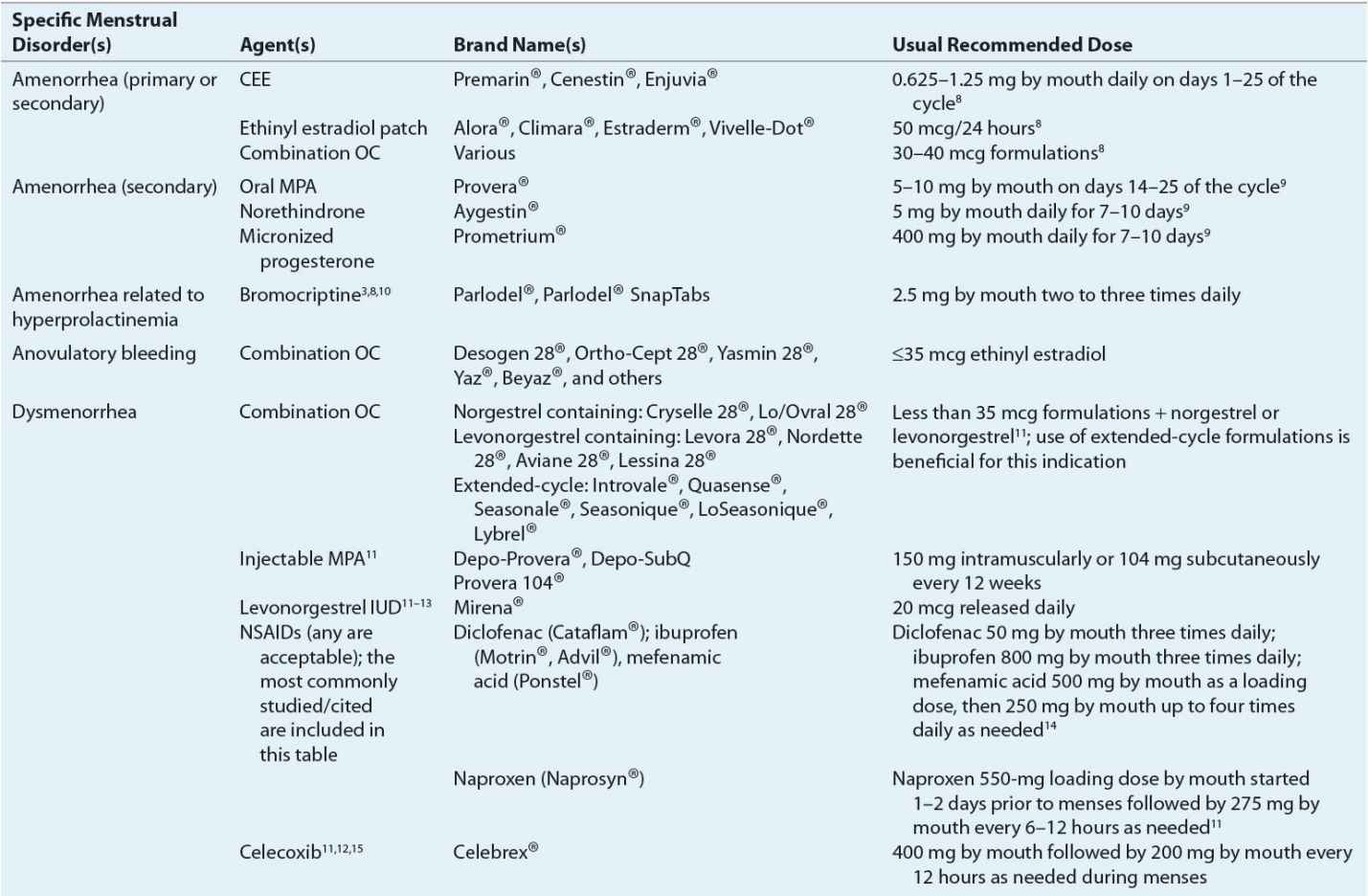

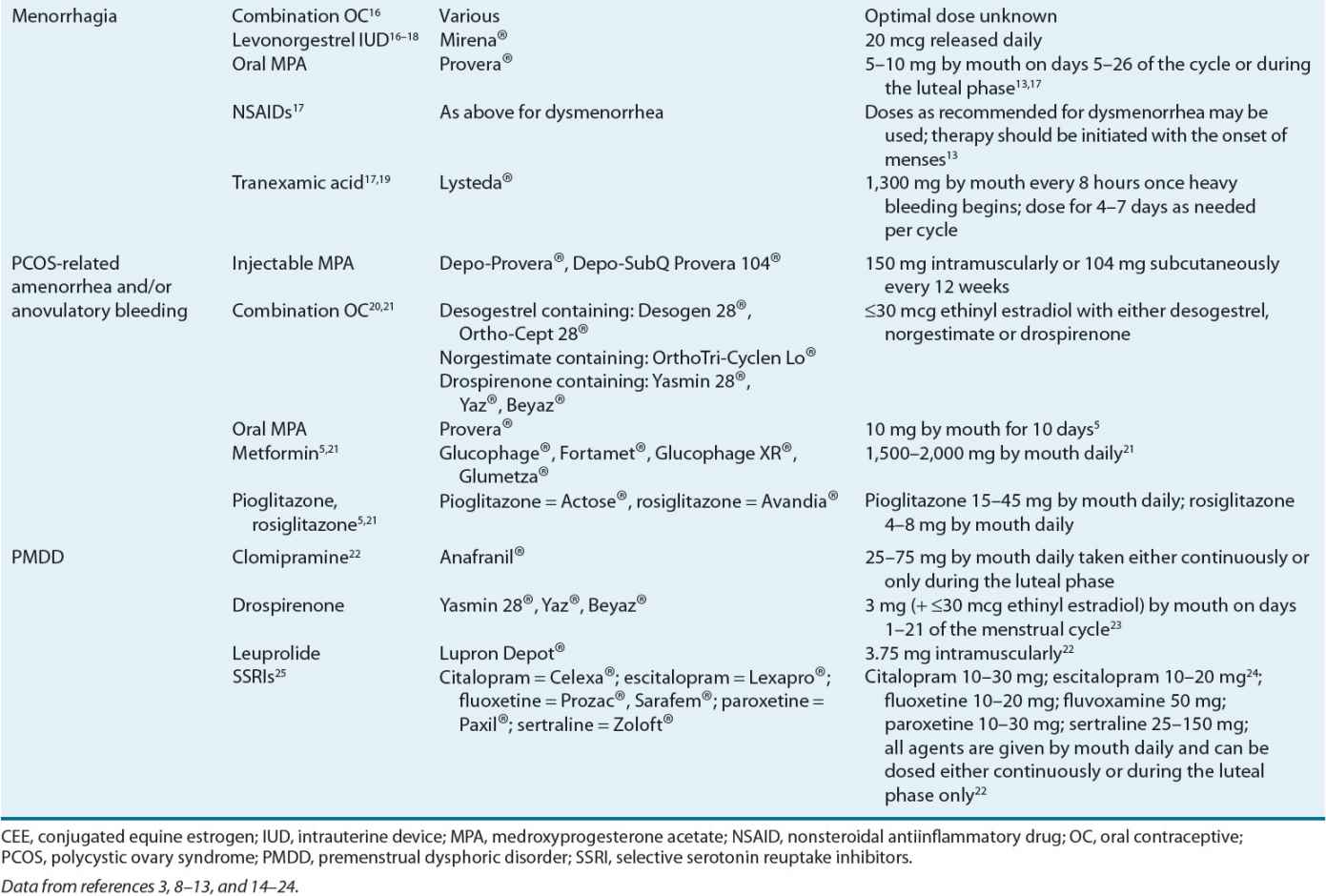

![]() For hypoestrogenic conditions associated with primary or secondary amenorrhea, estrogen (with a progestin) is provided. It can be administered as an oral contraceptive (OC), conjugated equine estrogen, or estradiol patch. Estrogen therapy in this patient population reduces osteoporosis risk7 and improves quality of life. Table 63-2 lists therapeutic agents for amenorrhea treatment, including recommended doses. Figure 63-2 illustrates a treatment algorithm for management of amenorrhea.

For hypoestrogenic conditions associated with primary or secondary amenorrhea, estrogen (with a progestin) is provided. It can be administered as an oral contraceptive (OC), conjugated equine estrogen, or estradiol patch. Estrogen therapy in this patient population reduces osteoporosis risk7 and improves quality of life. Table 63-2 lists therapeutic agents for amenorrhea treatment, including recommended doses. Figure 63-2 illustrates a treatment algorithm for management of amenorrhea.

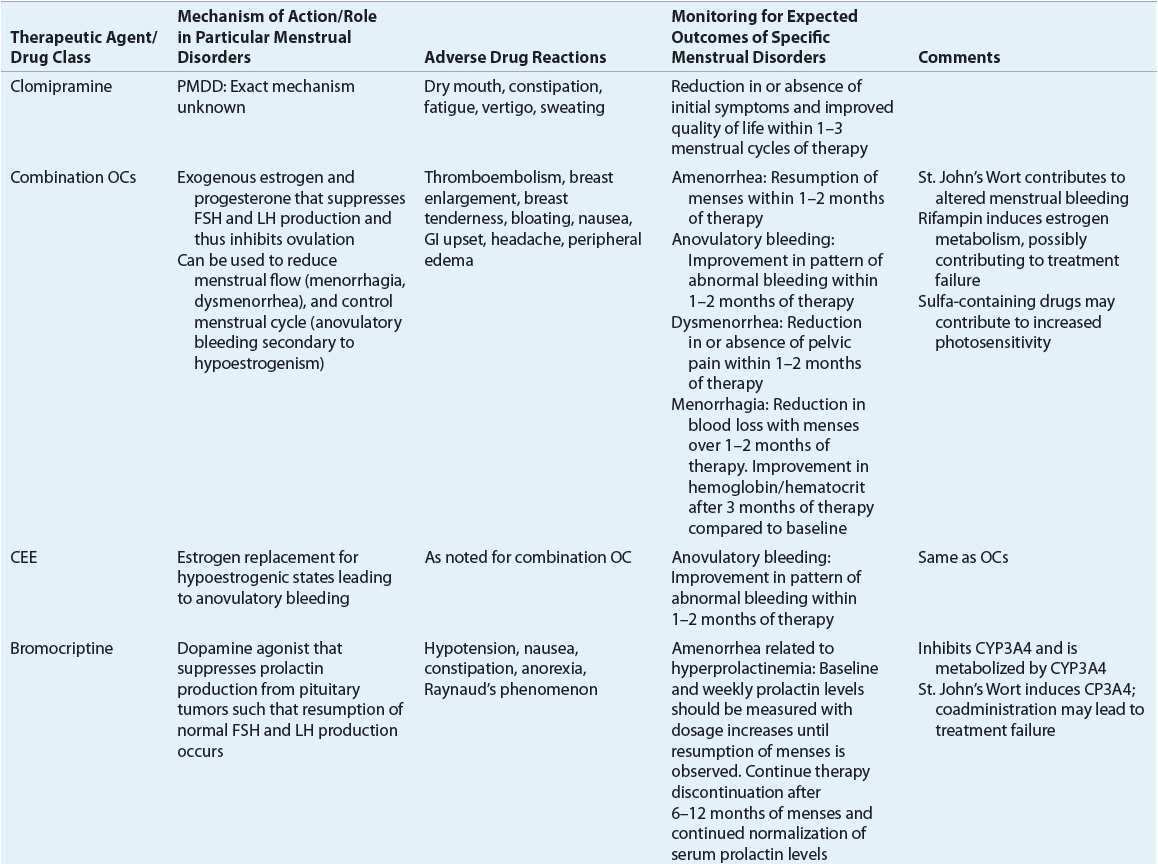

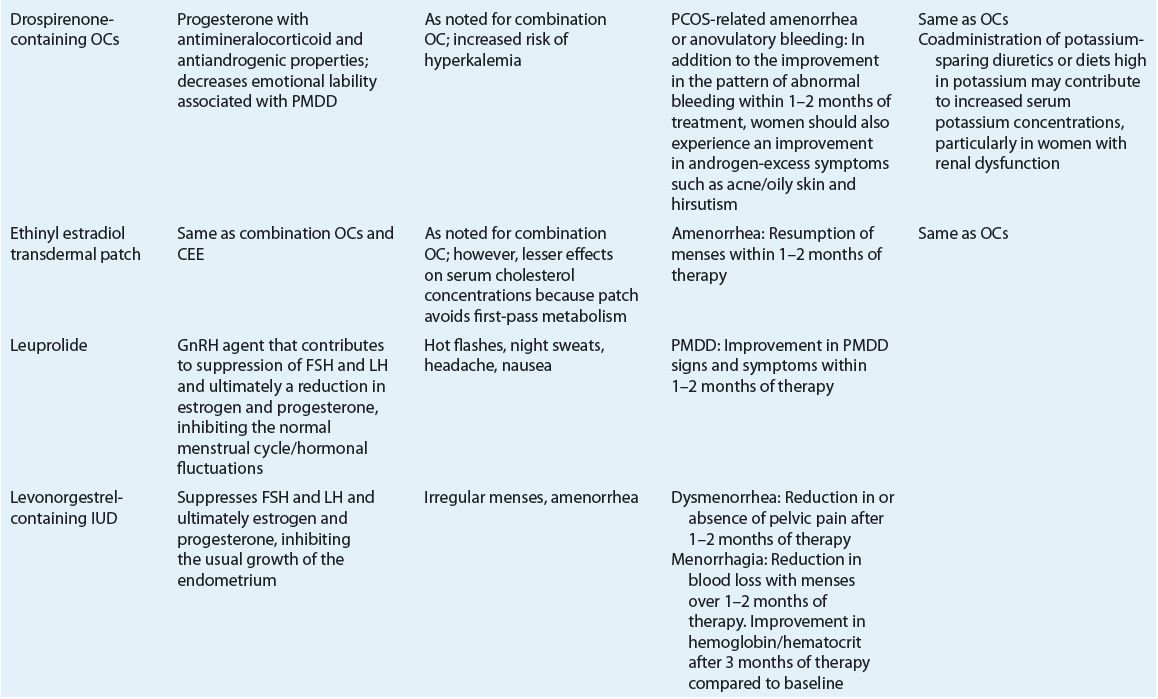

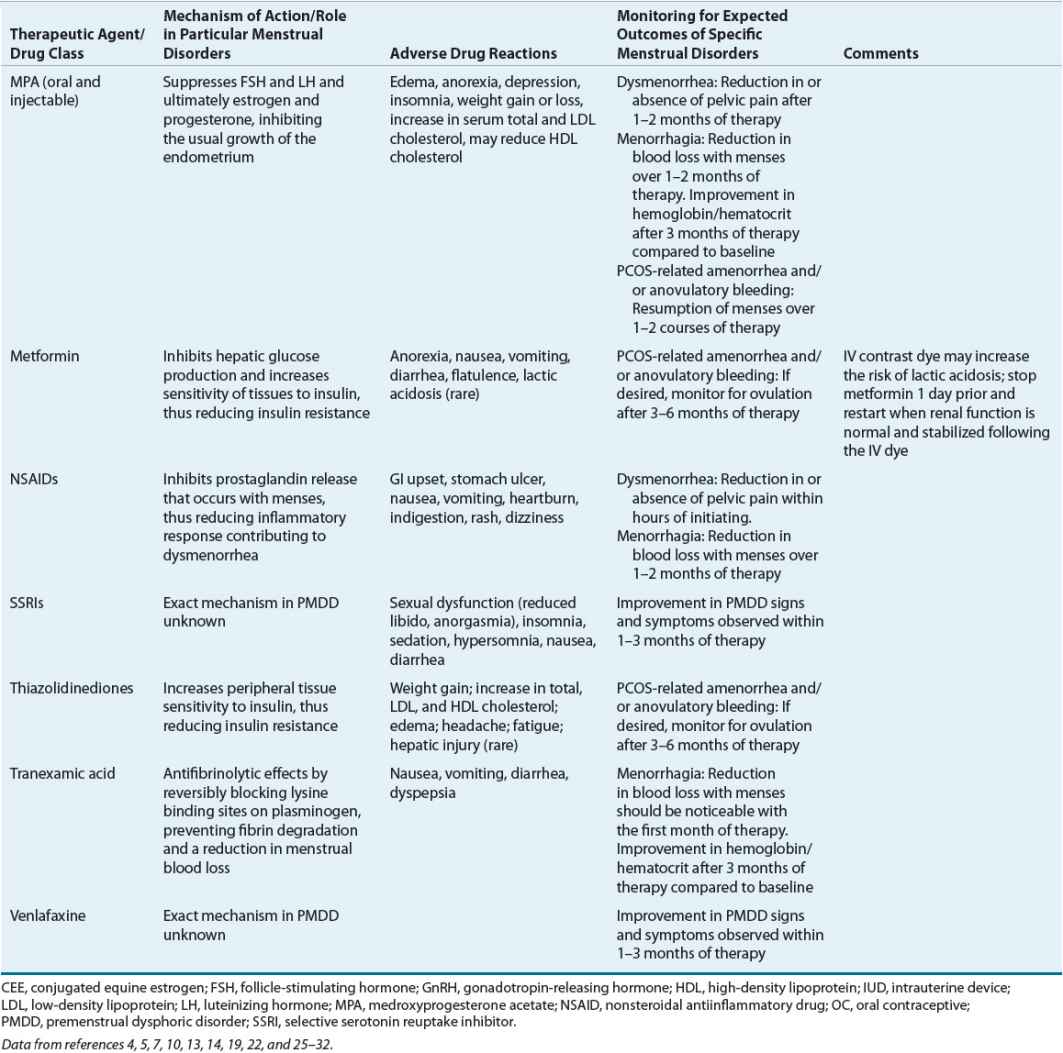

TABLE 63-2 Therapeutic Agents for Selected Menstrual Disorders

FIGURE 63-2 Treatment algorithm for amenorrhea. aRegardless of cause, adequate calcium and vitamin D intake must be ensured. (OC, oral contraceptive; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.)

When hyperprolactinemia is the cause of amenorrhea, dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine aid in reducing prolactin concentrations and the resumption of menses. Bromocriptine normalizes prolactin levels in 90% of affected women, and fertility is restored in 80% of treated women.10

Amenorrhea related to PCOS-induced anovulation may respond to agents that reduce insulin resistance. Metformin and the thiazolidinediones for this purpose are discussed in the “Anovulatory bleeding” section.

Progestins induce withdrawal bleeding in women with secondary amenorrhea. Several factors predict progesterone’s efficacy for this purpose.9 These factors include estrogen concentrations greater than or equal to 35 pg/mL (128 pmol/L) and endometrial thickness (greater initial thickness resulting in more withdrawal bleeding).

Progestin efficacy for secondary amenorrhea varies by formulation used. Progesterone in oil administered intramuscularly results in withdrawal bleeding in 70% of treated patients, whereas oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) induces withdrawal bleeding in 95% of treated patients.9 Table 63-2 identifies the types and doses of progestins used for secondary amenorrhea treatment. Figure 63-2 illustrates when to consider progestin use for amenorrhea treatment.

Special Populations

Amenorrhea in the adolescent population is of concern because this is the developmental time when peak bone mass is achieved. The cause of amenorrhea, whether primary or secondary, must be promptly identified in this population, as amenorrhea and its related hypoestrogenism negatively affect bone development. In addition to treating or eliminating amenorrhea’s underlying cause, ensuring that the patient is receiving adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D is imperative. Estrogen replacement, typically via an OC, is important.

Drug Class Information

Table 63-3 identifies the significant pharmacologic properties requiring monitoring of the agents used for amenorrhea management.

TABLE 63-3 Pharmacologic Properties and Monitoring Parameters for Agents Used in the Management of Menstrual Disorders

Evaluation of Therapeutic Outcomes

Table 63-3 lists the expected outcomes and specific monitoring parameters for treatment modalities used in amenorrhea management.

MENORRHAGIA

Menorrhagia is the term used to describe heavy menstrual blood loss (greater than 80 mL per cycle) or prolonged menstrual bleeding (menses for greater than 7 days).1,4 This definition has been questioned because of several factors, including difficulty quantifying menstrual loss in clinical practice. Additionally, many women with “heavy menses” but blood loss less than 80 mL merit treatment consideration because of flow containment issues, unpredictably heavy flow days, or other associated symptoms.28,32,33

Epidemiology

Menorrhagia rates in healthy women range from 9% to 14%.4 In women with coagulation disorders such as von Willebrand’s disease or platelet dysfunction, the rates of menorrhagia are as high as 100% and 98%, respectively.6,33

Etiology

![]() Causes of menorrhagia are either systemic disorders or specific uterine abnormalities.

Causes of menorrhagia are either systemic disorders or specific uterine abnormalities. ![]() Pregnancy, including intrauterine pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and miscarriage, must be at the top of the differential diagnosis list for any woman presenting with heavy menses. In several studies of adolescents with acute menorrhagia, underlying bleeding disorders accounted for 3% to 13% of emergency room presentations. For example, von Willebrand’s disease has an incidence of 1% in the general population;34 its prevalence in women with menorrhagia may be as high as 20%.35 Menorrhagia initially may present as heavy menses in the adolescent.34 Hypothyroidism also may be associated with heavy menses. Specific uterine causes of menorrhagia are more common in older childbearing women and include fibroids, adenomyosis, endometrial polyps, and gynecologic malignancies.

Pregnancy, including intrauterine pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, and miscarriage, must be at the top of the differential diagnosis list for any woman presenting with heavy menses. In several studies of adolescents with acute menorrhagia, underlying bleeding disorders accounted for 3% to 13% of emergency room presentations. For example, von Willebrand’s disease has an incidence of 1% in the general population;34 its prevalence in women with menorrhagia may be as high as 20%.35 Menorrhagia initially may present as heavy menses in the adolescent.34 Hypothyroidism also may be associated with heavy menses. Specific uterine causes of menorrhagia are more common in older childbearing women and include fibroids, adenomyosis, endometrial polyps, and gynecologic malignancies.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION Menorrhagia

Pathophysiology

Table 63-1 lists the pathophysiology of menorrhagia relative to the organ system(s) involved and the specific conditions that result in menorrhagia.

TREATMENT

Initial treatment choice for menorrhagia is influenced by whether or not the woman desires to become pregnant.

Desired Outcome

Menorrhagia therapy should reduce menstrual blood flow, improve the patient’s quality of life, and defer the need for surgical intervention. Table 63-2 lists the agents and their recommended dosing for menorrhagia management. Figure 63-3 presents an algorithm for menorrhagia treatment.

FIGURE 63-3 Treatment algorithm for menorrhagia. (IUD, intrauterine device; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; OC, oral contraceptive.)

General Approach to Treatment

Several treatment options exist for menorrhagia. Initial and subsequent treatment options should be thoughtfully chosen in an effort to avoid surgery.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Nonpharmacologic interventions for menorrhagia include surgical procedures that are generally reserved for patients not responding to pharmacologic treatment. These interventions vary from conservative endometrial ablation to hysterectomy.36

Pharmacologic Therapy

Among the agents used to treat menorrhagia, the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have the advantage of administration only during menses. NSAID use is associated with a 20% to 50% reduction in blood loss in 75% of treated women.13,32 In some patients, as much as an 80% reduction in blood loss has been observed.13

For women desiring to avoid pregnancy, OC use is beneficial for menorrhagia and should be considered. A 40% to 50% reduction in menstrual blood loss has been observed in patients treated with cyclic combined OCs.37 ![]() The reduction in menorrhagia-related blood loss with use of NSAIDs and OCs is directly proportional to the amount of pretreatment blood loss.13

The reduction in menorrhagia-related blood loss with use of NSAIDs and OCs is directly proportional to the amount of pretreatment blood loss.13

Another menorrhagia treatment option is the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (IUD). This is a very effective treatment to reduce menstrual flow.38 In particular, a 79% to 97% reduction in blood loss has been observed with its use.38 Its use has also resulted in postponing or cancelling scheduled endometrial ablation surgery or hysterectomy. Sixty percent of treated patients avoided hysterectomy when employing this treatment option,39 and its therapeutic efficacy is similar to endometrial ablation up to 2 years following treatment.18

Progesterone therapy either during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle or for 21 days, starting on day 5 after onset of menses, results in a 32% to 50% reduction in menstrual blood loss.13 However, progesterone use is not superior to other medical treatments, including the NSAIDs.13

Tranexamic acid was recently approved in the United States for primary menorrhagia treatment. Its use is associated with a significant 26% to 60% reduction in menstrual blood loss.40

Drug Treatments of First Choice

For women who have menorrhagia associated with ovulatory cycles and do not desire hormonal therapy and/or contraception, NSAIDs during menses is a reasonable choice in the absence of any contraindications or GI illnesses such as peptic ulcer disease or gastroesophageal reflux disease. This choice is convenient (only taken during menses) and comparatively inexpensive. For women desiring contraception, it is reasonable to start with either an OC or the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD. Either choice is acceptable for both nulligravid and multiparous women who desire a long-term reversible form of contraception.37,38 Given cost-effectiveness data, the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD is the best first-line choice for women desiring contraception.41 Clinical trial data illustrate a higher failure rate with the OCs (62.5%) compared to the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (34%) as the primary treatment method.41

Alternative Drug Treatments

Given their side effects, reduced efficacy compared to the first-line agents, and/or cost, use of oral progesterone and depot MPA should be reserved. Tranexamic acid is another treatment option. In comparison to luteal phase oral progesterone, tranexamic acid results in a significantly greater reduction in menstrual blood loss and greater relief of patient-reported symptoms.13 Its use has been associated with a significant improvement in quality of life and high patient satisfaction following three cycles of use.19,42

Special Populations

Although historically it was believed that IUD use should be avoided in nulliparous women, ![]() guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) indicate that both nulliparous and multiparous women at low risk of sexually transmitted diseases are good candidates for IUD use.38 Therefore, any of the treatments discussed are options in any female presenting with menorrhagia. Dosage adjustment for tranexamic acid is recommended for reduced renal function. Women with serum creatinine between 1.4 and 2.8 mg/dL (124 and 248 μmol/L) should receive only 1,300 mg by mouth twice daily; women with serum creatinine between 2.9 and 5.7 mg/dL (256 and 504 μmol/L) should receive 1,300 mg by mouth once daily; those with serum creatinine above 5.7 mg/dL (504 μmol/L) should receive 650 mg by mouth once daily.

guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) indicate that both nulliparous and multiparous women at low risk of sexually transmitted diseases are good candidates for IUD use.38 Therefore, any of the treatments discussed are options in any female presenting with menorrhagia. Dosage adjustment for tranexamic acid is recommended for reduced renal function. Women with serum creatinine between 1.4 and 2.8 mg/dL (124 and 248 μmol/L) should receive only 1,300 mg by mouth twice daily; women with serum creatinine between 2.9 and 5.7 mg/dL (256 and 504 μmol/L) should receive 1,300 mg by mouth once daily; those with serum creatinine above 5.7 mg/dL (504 μmol/L) should receive 650 mg by mouth once daily.

Drug Class Information

Table 63-3 identifies the significant pharmacologic properties that require monitoring for the agents used to manage menorrhagia.

Evaluation of Therapeutic Outcomes

Table 63-3 illustrates the expected outcomes and specific monitoring parameters for the treatment modalities used in menorrhagia management.

ANOVULATORY BLEEDING

![]() Anovulatory bleeding is the standard terminology used to describe bleeding from the uterine endometrium as a result of a dysfunctioning menstrual system, specifically excluding an anatomic lesion of the uterus.1,29 Anovulatory bleeding is also referred to as dysfunctional or irregular uterine bleeding.

Anovulatory bleeding is the standard terminology used to describe bleeding from the uterine endometrium as a result of a dysfunctioning menstrual system, specifically excluding an anatomic lesion of the uterus.1,29 Anovulatory bleeding is also referred to as dysfunctional or irregular uterine bleeding.

Epidemiology

Anovulatory bleeding is the most common form of noncyclic uterine bleeding.4 The most common cause is PCOS, for which the prevalence rates range from 6% to 8%.43–45 In fact, PCOS is the most common endocrine abnormality among U.S. women of reproductive age.45 ![]() PCOS can present as a variety of menstruation disorders, including amenorrhea, menorrhagia, and/or anovulatory bleeding. Although its exact definition continues to evolve, it is a disorder of androgen excess that often includes polycystic ovarian morphology and ovulatory dysfunction. It is a significant risk factor for the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and possibly cardiovascular disease.21,46,47 PCOS is a common cause of ovulation dysfunction in adult women.21 Other common causes in adult women include hyperprolactinemia, hypothalamic amenorrhea, also known as hypogonadotropichypogonadism, premature ovarian failure, and thyroid dysfunction.1,29

PCOS can present as a variety of menstruation disorders, including amenorrhea, menorrhagia, and/or anovulatory bleeding. Although its exact definition continues to evolve, it is a disorder of androgen excess that often includes polycystic ovarian morphology and ovulatory dysfunction. It is a significant risk factor for the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and possibly cardiovascular disease.21,46,47 PCOS is a common cause of ovulation dysfunction in adult women.21 Other common causes in adult women include hyperprolactinemia, hypothalamic amenorrhea, also known as hypogonadotropichypogonadism, premature ovarian failure, and thyroid dysfunction.1,29

Etiology

When considering the etiology of anovulatory bleeding, the patient’s age must be considered. All patients presenting with abnormal bleeding should be evaluated for pregnancy. Most adolescents will experience physiologic anovulatory cycles in the first few years following menarche because their hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis is still maturing. However, if an adolescent has not developed regular menstrual cycles within 5 years of menarche, further evaluation for the cause, such as PCOS, should be considered.48 Anovulatory cycles may “unmask” an underlying bleeding disorder. When irregular menses is associated with significant bleeding, an inherited bleeding disorder should be a considered cause, especially in adolescence.6,29 Women experiencing anovulation in their reproductive years should be evaluated for pathologic causes, including PCOS, thyroid dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia, primary pituitary disease, premature ovarian failure, hypothalamic dysfunction, disordered eating, adrenal disease, and androgen-producing tumors. Women in their perimenopausal years may experience “physiologic” anovulatory cycles because of intermittently declining estrogen levels. Regardless of age, evaluation for endometrial hyperplasia and/or endometrial cancer should be considered when a woman experiences excessive bleeding with anovulatory cycles. When considering the etiology of anovulation, it is common for several conditions to coexist (e.g., PCOS and hypothyroidism), each contributing to the woman’s constellation of symptoms. All common etiologies should be considered when beginning to evaluate anovulation.1

Pathophysiology

Normal menstrual cycles occur through a complex interaction of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, ovaries, and endometrium (Fig. 63-1). In an ovulatory cycle, the ovary produces a mature, estrogen-secreting follicle in response to FSH release from the pituitary. The endometrium proliferates under the influence of this estrogen production. At a critical level of estrogen concentration, the pituitary responds by producing an “LH surge,” which creates a cascade of ovarian events, culminating in ovulation. Upon oocyte release, the follicle becomes a progesterone-producing corpus luteum. The endometrium “organizes” into secretory endometrium in the presence of adequate progesterone. If conception and implantation do not occur, corpus luteum involution causes a decline in estrogen and progesterone leading to predictable, organized menstrual flow as the endometrium sloughs.

If ovulation does not occur, progesterone is not produced, and the endometrium will continue to proliferate in an “unorganized” fashion under the influence of continued estrogen production. Eventually the endometrium will become so thick that it can no longer be supported by continued estrogen production. This results in unorganized, sporadic sloughing of the endometrium, characteristic of the unpredictable and heavy bleeding of anovulation. Anovulation has several etiologies. In adolescence, hypothalamic–pituitary axis immaturity contributes to the absence of the LH surge required for ovulation. In the anorexic patient, the hypothalamus loses much of its pulsatile GnRH release, leading to low levels of FSH and LH, enough for estrogen production but not enough to induce ovulation.

TREATMENT

Optimizing anovulatory bleeding therapy depends on accurate identification of the disorder’s cause(s). The treatment options for anovulatory bleeding are wide and varied.

Desired Outcome

Control of excessive bleeding in the short-term is paramount. Longer-term goals of therapy include restoring the natural cycle of orderly endometrial growth and shedding,29,49 decreasing anovulation complications (e.g., osteopenia, infertility), and improving overall quality of life. Table 63-2 identifies the agents used to manage anovulatory bleeding and their recommended doses.

General Approach to Treatment

Although the appropriate primary treatment choice for anovulatory bleeding depends on the accurate diagnosis of its cause and identification of desired outcomes, additional treatment may be necessary to manage other signs and symptoms. Treatment to resolve anovulatory bleeding should be initiated and any underlying menorrhagia should be managed.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Nonpharmacologic treatment options for anovulatory bleeding depend on the underlying cause. In a woman of reproductive age with PCOS, moderate weight loss of 2% to 5% may result in improved menstrual regularity and ovulatory function, reduced hirsutism, increased insulin sensitivity, and improved response to fertility treatments.21 In women who have completed childbearing or who have not responded to medical management, endometrial ablation or resection and hysterectomy are surgical options. Procedure choice involves shared decision making with the patient. In the short term, ablation results in less morbidity and shorter recovery periods. However, a significant number of women eventually undergo hysterectomy in the subsequent 5 years.29

Pharmacologic Therapy

Estrogen is the recommended treatment for managing acute severe bleeding episodes because it promotes endometrial stabilization.49 Following its initial use to control acute bleeding episodes, therapy continuation may be necessary to prevent future occurrences. OC use fulfills this role and contributes to predictable menstrual cycles.

OCs prevent recurrent anovulatory bleeding by providing a progestin and suppressing ovarian hormones and adrenal androgen production. They also, indirectly, increase sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). SHBG binds androgens and reduces their circulating free concentrations. For women with high androgen levels and its related signs such as hirsutism (e.g., those with PCOS) OCs containing less than or equal to 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol and a progesterone that exhibits minimal androgenic side effects (e.g., norgestimate and desogestrel) or with antiandrogenic effects (e.g., drospirenone) may be desirable.20