Chapter 35 Herbal medicine in Britain and Europe

regulation and practice

REGULATORY BACKGROUND

The supply of herbs as healthcare products in Europe is more tightly regulated than other commodities. It is also notoriously complex, covering over-the-counter sales through various outlets, as well provision of ‘phytomedicines’ by health professionals (i.e. doctors and pharmacists in most of Europe and herbal practitioners in the UK and Ireland). The vague and less regulated ‘borderline’ area within which many natural products have been supplied direct to the consumer is becoming much more constrained and is intended to disappear altogether after 2010. Essentially, in the case of the direct sale of herbs, there are two regulatory options: food supplements or medicinal products.

In Germany, France and the United Kingdom especially, a large number of herbal medicinal products have obtained marketing authorizations, according to laws within each member state but within theterms of this European legislation. Nevertheless, the governments of Germany, France, the Netherlands and the UK provided exemptions in their own national legislatures to protect herbal medicines from some of the requirements imposed upon synthetic drug manufacturers. These exemptions were highlighted in a report to the European Commission in 1999 and have led to moves for greater harmonization of herbal regulations within new applications of the pivotal 65/65/EEC Directive. The first amendment was enacted quickly and allowed products with ‘established use’ as medicines to establish their efficacy by reference to this use.

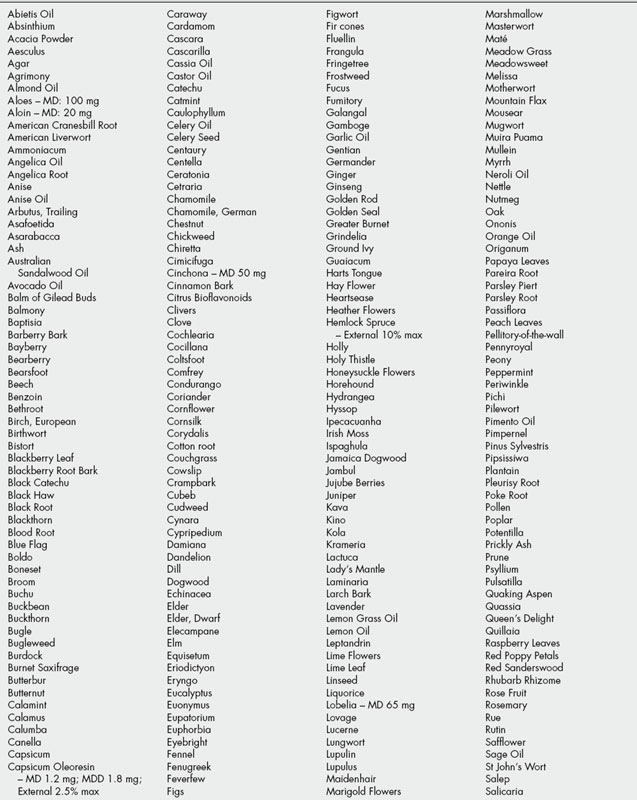

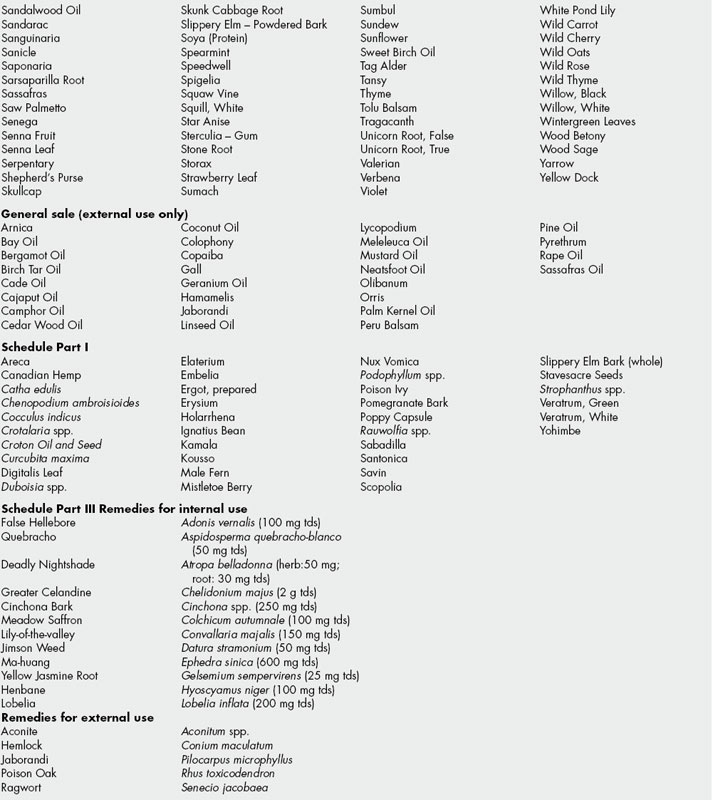

Although 12.2 has fallen, the General Sale List (GSL) still is referred to as a directory of herbal remedies. Over 300 herbal substances are named for internal use (Schedule 3[A]). Some 30 are listed for external use (Schedule 3[B]). Where maximum doses (MD) or maximum daily doses (MDD) are listed for GSL products it is implied that any dose in excess of that figure cannot be marketed over the counter (OTC) and the medicine becomes prescription only. Herbal remedies on the various schedules are listed in Table 35.1.

INDUSTRY STANDARDS

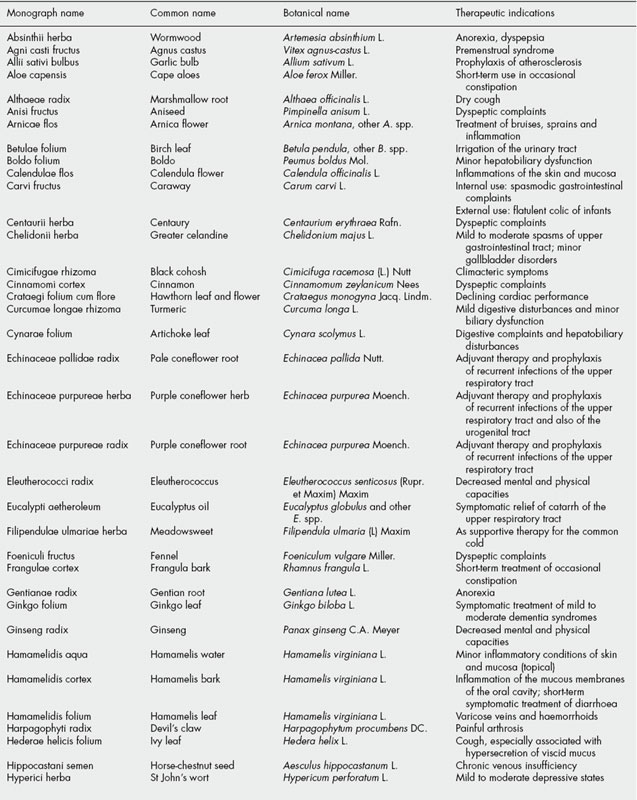

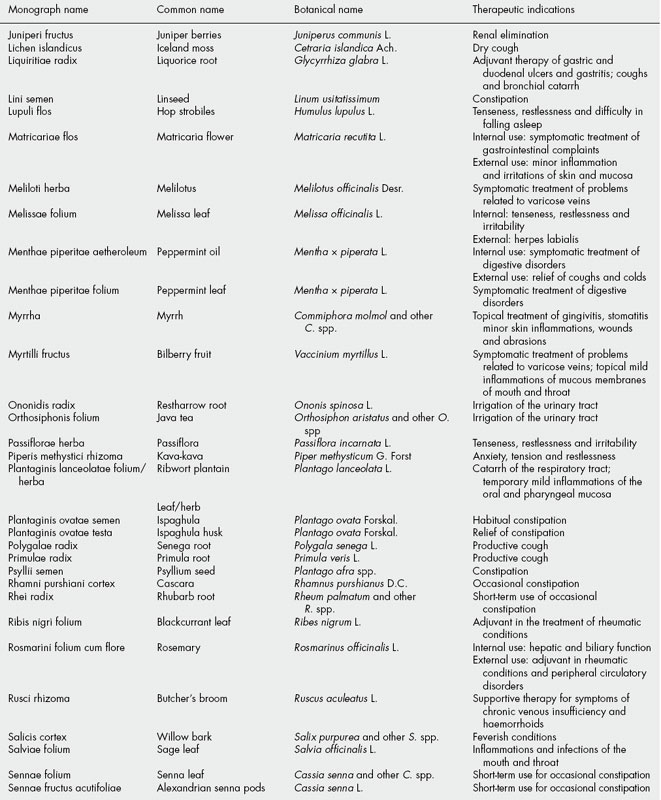

The British Herbal Medicine Association (BHMA) has, since its founding in 1964, engaged the legislature in productive discussions about the controls of herbal medicines. Its most prominent achievement has been the production of the British Herbal Pharmacopoeia, first in 1983 and then, through substantial revisions, to the latest, with 169 monographs published in 1996. The Pharmacopoeia has been widely used by regulators in the UK and elsewhere around the world as an effective practical quality standard where official monographs do not exist. The herbal monographs covered in the final 1996 edition are listed in Table 35.2.

Table 35.2 Monographs in the British Herbal Pharmacopoeia 1996.

| Monograph name | Botanical name | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Agnus castus | Vitex agnus-castus L. | Hormonal modulator |

| Agrimony | Agrimonia spp. | Astringent |

| Aloes, Barbados | Aloe barbadensis Miller. | Stimulant laxative |

| Aloes, Cape | Aloe ferox Miller. | Stimulant laxative |

| Ammoniacum | Dorema ammoniacum | Expectorant |

| Angelica root | Angelica archangelica L. | Aromatic bitter, spasmolytic |

| Aniseed | Pimpinella anisum L. | Expectorant; carminative |

| Arnica flower | Arnica montana L. | Topical healing |

| Artichoke | Cynara scolymus L. | Hepatic |

| Asafoetida | Ferula assa-foetida and other F. spp. | Spasmolytic |

| Ascophyllum | Ascophyllum nodosum Le Jol. | Thyroactive |

| Balm leaf | Melissa officinalis L. | Sedative; topical antiviral |

| Balm of Gilead bud | Populus nigra and other P. spp. | Expectorant |

| Barberry bark | Berberis vulgaris L. | Cholagogue |

| Bayberry bark | Myrica cerifera L. | Astringent |

| Bearberry leaf | Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Spreng | Urinary antiseptic |

| Belladonna herb | Atropa belladonna L. | Antispasmodic |

| Birch leaf | Betula pendula and other B. spp. | Diuretic; antirheumatic |

| Black cohosh | Cimicifuga racemosa Nutt | Anti-inflammatory |

| Black haw bark | Viburnum prunifolium L. | Spasmolytic |

| Black horehound | Ballota nigra L. | Anti-emetic |

| Bladderwrack | Fucus vesiculosis L. | Thyroactive |

| Blue flag | Iris versicolor, I. caroliniana Watson | Laxative |

| Bogbean | Menyanthes trifoliata L. | Bitter |

| Boldo | Peumus boldus Molina | Cholagogue |

| Broom top | Cytisus scoparius Link. | Anti-arrhythmic, diuretic |

| Buchu | Barosma betulina Bartl. et Wendl. | Urinary antiseptic |

| Burdock leaf | Arctium lappa L. A. minus Bernh. | Dermatological agent |

| Burdock root | Arctium lappa L. A. minus Bernh. | Dermatological agent |

| Calamus | Acorus calamus vars | Carminative |

| Calumba root | Jateorhiza palmata Miers. | Appetite stimulant |

| Caraway | Carum carvi L. | Carminative |

| Cardamom fruit | Elettaria cardamomum Maton. | Carminative |

| Cascara | Rhamnus purshianus DC. | Stimulant laxative |

| Cassia bark | Cinnamomum cassia Blume. | Carminative |

| Catechu | Uncaria gambier (Hunter) Roxb. | Astringent |

| Cayenne pepper | Capsicum frutescens L. | Rubefacient, vasostimulant |

| Celery seed | Apium graveolens L. | Diuretic |

| Centaury | Centaurium erythraea Rafn. | Bitter |

| Cinchona bark | Cinchona pubescens Vahl. | Bitter |

| Cinnamon | Cinnamomum zeylanicum Nees. | Carminative |

| Clivers | Galium aparine L. | Diuretic |

| Clove | Syzygium aromaticum L. | Carminative, topical analgesic |

| Cocillana | Guarea rusbyi | Expectorant |

| Cola | Cola nitida, C. acuminata | Central nervous stimulant |

| Comfrey root | Symphytum officinale L. | Vulnerary |

| Coriander | Coriandrum sativum L. | Carminative, stimulant |

| Corn Silk | Zea mays L. | Diuretic; urinary demulcent |

| Couch grass rhizome | Agropyron repens P. Beauv. | Diuretic |

| Cranesbill root | Geranium maculatum L. | Astringent |

| Damiana | Turnera diffusa and possibly other spp. | Thymoleptic |

| Dandelion leaf | Taraxacum officinale Webber. | Diuretic; choleretic |

| Dandelion root | Taraxacum officinale Webber. | Hepatic |

| Devil’s claw | Harpagophytum procumbens DC. | Antirheumatic |

| Echinacea root | Echinacea angustifolia DC. | Immunostimulant |

| Elder flower | Sambucus nigra L. | Diaphoretic |

| Elecampane | Inula helenium L. | Expectorant |

| Eleutherococcus | Eleutherococcus senticosus Maxim. | Adaptogen; tonic |

| Equisetum | Equisetum arvense L. | Diuretic; astringent |

| Eucalyptus leaf | Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Antiseptic |

| Euonymus bark | Euonymus atropurpureus Jacq. | Laxative |

| Fennel, bitter | Foeniculum vulgare Miller. | Carminative |

| Fennel, sweet | Foeniculum vulgare Miller. | Carminative |

| Fenugreek seed | Trigonella foenum-graecum L. | Demulcent, hypoglycaemic |

| Feverfew | Tanacetum parthenium Schultz Bip. | Migraine prophylactic |

| Frangula bark | Rhamnus frangula L. | Stimulant laxative |

| Fumitory | Fumaria officinalis L. | Choleretic |

| Galangal | Alpinia officinarum Hance. | Carminative |

| Garlic | Allium sativum L. | Hypolipidaemic; antimicrobial |

| Gentian | Gentiana lutea L. | Bitter |

| Ginger | Zingiber officinale Roscoe. | Carminative; anti-emetic |

| Ginkgo leaf | Ginkgo biloba L. | Vasoactive; platelet aggregation inhibitor |

| Ginseng | Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer. | Adaptogen; tonic |

| Goldenrod | Solidago virgaurea L. | Diuretic; anticatarrhal, diaphoretic |

| Goldenseal root | Hydrastis canadensis L. | Anti-inflammatory |

| Grindelia | Grindelia robusta Nutt. | Expectorant |

| Ground ivy | Glechoma hederacea L. | Expectorant |

| Guaiacum resin | Guaiacum officinale L. G. Sanctum L. | Anti-inflammatory |

| Hamamelis bark | Hamamelis virginiana L. | Astringent |

| Hamamelis leaf | Hamamelis virginiana L. | Astringent |

| Hawthorn berry | Crataegus monogyna Jacq. | Cardiotonic |

| Hawthorn flowering top | Crataegus monogyna Jacq. | Cardiotonic |

| Heartsease | Viola tricolor L. | Expectorant; dermatological agent |

| Helonias | Chamaelirium luteum A. Gray. | Uterine tonic |

| Holy Thistle | Cnicus benedictus L. | Bitter |

| Hops | Humulus lupulus L. | Sedative; bitter |

| Horse-chestnut seed | Aesculus hippocastanum L. | Venoactive |

| Hydrangea | Hydrangea arborescens L. | Diuretic |

| Hyoscyamus leaf | Hyoscyamus niger L. | Antispasmodic |

| Hyssop | Hyssopus officinalis L. | Expectorant |

| Iceland moss | Cetraria islandica L. | Demulcent |

| Ipecacuanha | Cephaelis ipecacuanha, C. acuminata | Expectorant; emetic |

| Irish moss | Chondrus crispus Stackh. | Demulcent |

| Ispaghula husk | Plantago ovata Forssk. | Bulk-forming laxative |

| Ispaghula seed | Plantago ovata Forssk. | Bulk-forming laxative |

| Jamaica dogwood | Piscidia piscipula Sarg. | Analgesic |

| Java tea | Orthosiphon aristatus, (Blume) Miq. | Diuretic |

| Juniper berry | Juniperus communis L. | Diuretic |

| Kava-kava | Piper methysticum G. Forst. | Anxiolytic |

| Lady’s mantle | Alchemilla xanthochlora, Rothm. A. vulgaris L. S. l. | Astringent |

| Lily of the valley leaf | Convallaria majalis L. | Cardioactive |

| Lime flower | Tilia cordata Mill. and other spp. | Antispasmodic; diaphoretic |

| Linseed | Linum usitatissimum L. | Bulk forming laxative; demulcent |

| Liquorice root | Glycyrrhiza glabra L. | Respiratory stimulant |

| Lobelia | Lobelia inflata L. | Respiratory stimulant |

| Lovage root | Levisticum officinale Koch. | Carminative; mild diuretic |

| Lucerne | Medicago sativa L. | Tonic |

| Marigold | Calendula officinalis L. | Anti-inflammatory, vulnerary |

| Marshmallow leaf | Althaea officinalis L. | Demulcent |

| Marshmallow root | Althaea officinalis L. | Demulcent |

| Maté | Ilex paraguariensis A. St.-Hil. | Stimulant |

| Matricaria flower | Matricaria recutita L. | Anti-inflammatory; antispasmodic |

| Meadowsweet | Filipendula ulmaria Maxim. | Anti-inflammatory |

| Melilot | Melilotis officinalis Pall. | Venotonic, vulnerary |

| Milk thistle fruit | Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. | Hepatoprotective |

| Mistletoe herb | Viscum album L. | Hypotensive |

| Motherwort | Leonurus cardiaca L. | Antispasmodic |

| Mugwort | Artemisia vulgaris L. | Emmenogogue |

| Mullein leaf | Verbascum densiflorum Bertol. | Expectorant |

| Myrrh | Commiphora molmol Engler and other spp. of C. | Antiseptic |

| Nettle herb | Urtica dioica L. | Diuretic |

| Nettle root | Urtica dioica L. | Prostatic |

| Oak bark | Quercus robur L. and other Q. spp. | Astringent |

| Parsley herb | Petroselinum crispum | Diuretic |

| Parsley root | Petroselinum crispum | Carminative, diuretic |

| Passiflora | Passiflora incarnata L. | Sedative |

| Peppermint leaf | Mentha piperata L. | Carminative |

| Pilewort herb | Ficaria ranunculoides Moench. | Astringent |

| Poke root | Phytolacca americana L. | Anti-inflamatory |

| Prickly ash bark | Zanthoxylum clava-herculis L. | Circulatory stimulant |

| Psyllium seed | Plantago afra L. P. indica L. | Bulk-forming laxative |

| Pulsatilla | Pulsatilla vulgaris Miller, P. pratensis (L.) Miller | Sedative |

| Pumpkin seed | Cucurbita pepo L. | Prostatic |

| Quassia | Picrasma excelsa | Appetite stimulant |

| Queen’s delight | Stillingia sylvatica L. | Expectorant |

| Raspberry leaf | Rubus idaeus L. | Partus praeparator |

| Red clover flower | Trifolium pratense L. | Anti-inflammatory |

| Rhatany root | Krameria triandra Ruiz and Pavon. | Astringent |

| Rhubarb | Rheum palmatum L., R. officinale Baillon, hybrids | Laxative |

| Roman chamomile flower | Chamaemelum nobile All. | Antispasmodic |

| Rosemary leaf | Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Carminative, spasmolytic |

| Sage leaf | Salvia officinalis L. | Antiseptic, astringent |

| Sarsaparilla | Smilax spp. | Anti-inflammatory |

| Saw palmetto fruit | Serenoa repens | Prostatic |

| Senega root | Polygala senega L. and related spp. | Expectorant |

| Senna fruit, Alexandrian | Cassia senna L. | Stimulant laxative |

| Senna fruit, Tinnevelly | Cassia angustifolia Vahl. | Stimulant laxative |

| Senna leaf | Cassia senna, C. angustifolia | Stimulant laxative |

| Shepherd’s purse | Capsella bursa-pastoris Medik. | Antihaemorrhagic |

| Skullcap | Scutellaria lateriflora L. | Mild sedative |

| Slippery elm bark | Ulmnus rubra Muhl. | Demulcent |

| Squill | Drimia maritima Stearn. | Expectorant |

| Squill, Indian | Drimia indica J.P. Jessop. | Expectorant |

| St John’s wort | Hypericum perforatum L. | Antidepressant |

| Stramonium leaf | Datura stramonium L. | Antispasmodic |

| Thyme | Thymus vulgaris, T. zygis | Expectorant |

| Valerian root | Valeriana officinalis L. | Sedative |

| Vervain | Verbena officinalis L. | Tonic |

| Violet leaf | Viola odorata L. | Expectorant |

| White deadnettle | Lamium album L. | Astringent |

| White horehound | Marrubium vulgare L. | Expectorant |

| Wild carrot | Daucus carota L. | Diuretic |

| Wild cherry bark | Prunus serotina Ehrh. | Antitussive |

| Wild lettuce | Lactuca virosa L. | Sedative |

| Wild thyme | Thymus serpyllum L. | Expectorant |

| Wild yam | Dioscorea villosa L. | Spasmolytic, anti-inflammatory |

| Willow bark | Salix alba L. and other spp. | Anti-inflammatory |

| Wormwood | Artemesia absinthium L. | Bitter |

| Yarrow | Achillea millefolium L. | Diaphoretic |

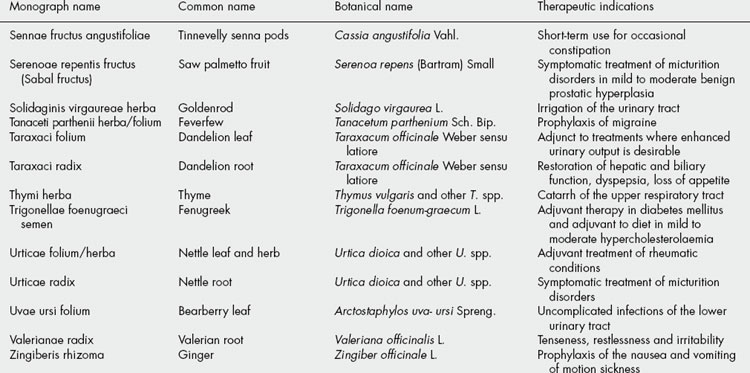

The BHMA is also the UK member of a European network of national herbal or phytotherapy associations called the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP). Since its formation in 1989, ESCOP has been involved in producing harmonized therapeutic monographs for ‘plant drugs’ as formal submissions to the European medicines regulators. A total of 80 such monographs have been published, listed in Table 35.3. More details of this work can be obtained at the ESCOP website (http://www.escop.com).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree