Otolaryngologists and speech-language pathologists (SLPs) work closely together to provide comprehensive services to patients with disorders and diseases of the head and neck because of the effect of these structures on communication and swallowing. Although not all otolaryngologic patients require intervention by an SLP, knowledge of the more commonly encountered disorders and their effect on speech and swallowing functions is crucial. Medical treatment and surgical resection and repair can result in posttreatment effects that require management by an SLP.

This chapter discusses the process by which the otolaryngologist diagnoses head and neck disorders; diseases and disorders of the oral cavity, oropharynx, and nasopharynx; nasal sinus disorders; laryngeal anatomy and physiology; laryngeal disorders, trauma, and tracheostomy; special medical issues of the professional voice; laryngopharyngeal reflux disease; and head and neck manifestations in AIDS.

18.1 History and Physical Examination

When a patient presents to an otolaryngologist with a complaint referable to the upper airway or head and neck, the first and perhaps most critical part of the assessment is obtaining a thorough history. During the history taking, the otolaryngologist establishes a relationship with the patient and begins the mutual exchange of information in a manner that breeds trust. Traditionally, the history begins with a clarification of the chief complaint in an attempt to identify factors that are pertinent to the subsequent evaluation and treatment. The time since onset, the severity of the symptoms, whether or not the symptoms vary by time of day or exposure to certain environments or conditions, and any previous treatment for the condition should be obtained. It is important, however, not to become so focused on the main complaint that important peripheral information pertinent to the disorder or other conditions that may require assessment are ignored. A general review of other head and neck symptoms follows, and then questions are asked regarding general medical health and other medical problems. A list of medications and a history of previous diseases or surgeries should be obtained. Any habits that might influence health should be considered, particularly eating habits and whether or not the individual uses tobacco or alcohol. One cannot underestimate the power of the history, in that often the physician can arrive at a tentative diagnosis prior to any physical contact with the patient.

The head and neck physical examination usually begins during the history. At that time, the physician assesses speech and voice, assesses gross hearing, and notices any abnormalities of facial movement or skin conditions or masses. It is important during the head and neck exam not to focus only on the area related to the chief complaint; by doing so, important physical findings may be missed. To avoid missing anything, it is reasonable to follow a sequence of evaluations despite the presenting disorder. The skin and scalp are usually evaluated first, followed by an examination of the ears. The external ear and ear canal are assessed with an otoscope to identify inflammation or skin conditions. The middle ear is examined for normal landmarks and absence of infection, masses, fluid, or retraction of the eardrum. Air insufflation (pneumatic otoscopy) is particularly useful in evaluating middle ear function, negative pressure, or fluid. If any concerns are raised during otoscopy, a microscope can be used to improve visualization of any potential abnormalities. Hearing can be assessed with the use of tuning forks, although if any concerns are raised related to hearing, a formal audiogram is recommended.

The nasal examination is generally obtained with a head mirror, indirect light, and a nasal speculum. Decongesting the nose with a decongestant spray improves the view into the more posterior aspects of the nose. If concerns are raised, if seeing the nasal cavity is difficult, or if a diagnosis needs confirmation, Benninger 1 recommends the use of a nasal endoscope to better examine the entire nose. The oral cavity is examined with a mirror and indirect light so that two hands can be used to manipulate the tongue and other mucosal surfaces. All areas should be seen. Tongue blades depress the tongue to expose the oropharynx, tonsils, and tongue base. Keeping the tongue blades just anterior to the junction of the anterior two-thirds and posterior one-third of the tongue and having the patient gently breathe will help minimize gagging. With the tongue depressed, a nasopharyngeal mirror can be used to assess the nasopharynx.

The larynx typically is initially examined by indirect laryngoscopy with a laryngeal mirror. The tongue is grasped and gently pulled forward. The mirror is inserted to a point just anterior to the soft palate and light is directed to the mirror; the light reflects onto the hypopharynx and larynx. Avoiding contact with the pharyngeal wall and base of the tongue or having the patient phonate prior to placing the mirror will minimize the gag reflex. Approximately two-thirds of patients can be examined well with a mirror. It is important not to focus only on the vocal folds, as other important findings related to the base of tongue, posterior pharyngeal walls, piriform sinuses, epiglottis, and valleculae may be missed. Having the patient say different vowel sounds provides different visual angles to the larynx. Indirect laryngoscopy enables a global view of the larynx and should be performed prior to any further techniques of examining the larynx, although it is limited, in that the larynx cannot be seen during running speech or singing. To supplement the mirror view, and to view the larynx during running speech, or if the exam is limited, a flexible laryngoscope is used. Usually it is passed through the nose after decongestion and occasionally after application of a topical anesthetic. Not only is this instrument valuable in laryngeal assessment, but also it can be used to better see the nasopharynx and it can be used for functional endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) or, as Bastian 2 notes, for voice modification or biofeedback training. According to Benninger, 3 video images can be recorded for following the progress of treatment, for documentation, and to aid in discussions with the patient, family, or referring physician. To further augment the examination of the larynx, videostroboscopy of the larynx can be performed to assess vocal fold vibration.

The neck should be palpated for any masses, neck muscle problems, or asymmetry. The thyroid is then palpated at rest and during swallowing. Pulsating masses can be auscultated with a stethoscope while listening for bruits to help identify a vascular lesion. If a nonpulsatile mass is detected, fine-needle aspiration is a useful tool in obtaining a pathological diagnosis and in many case it has eliminated the need for open biopsy.

Assessment of the cranial nerves is part of the routine examination, whereas selective assessment of balance function should be performed if a balance disorder is suggested by the preceding evaluation. A general physical examination is usually not performed on a routine basis by an otolaryngologist, although selected exams, such as of the lungs or heart, may be performed if prompted by the history and physical examination.

The need for other tests is determined by the findings of the history and physical examination. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are very useful in assessing head and neck masses or tumors and in ruling out intracranial or skull base disease. CT scans are particularly useful in evaluating sinus disease. A chest X-ray is helpful in patients with head and neck tumors, cough, or hemoptysis. Swallowing and gastroesophageal reflux assessment may be considered in patients with swallowing complaints. Other medical evaluations are performed as determined by the disease suspected. On occasion, an evaluation under anesthesia may be necessary to stage cancer, to obtain biopsies, or to clarify the diagnosis.

18.2 Oral Cavity, Oropharynx, and Nasopharynx

18.2.1 Anatomy

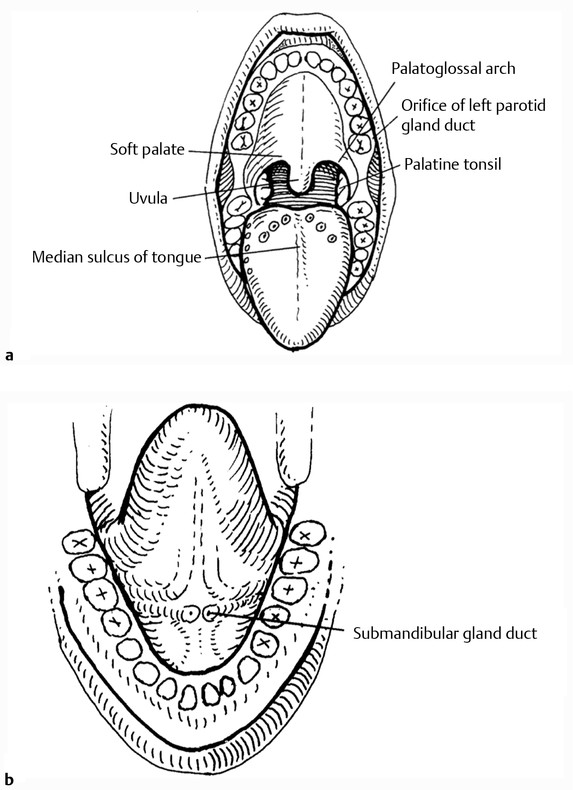

The boundaries of the oral cavity are the lips anteriorly, the buccal (cheek) mucosa laterally, the anterior tonsillar pillars posteriorly, the hard palate superiorly, and the floor of mouth inferiorly. The oral cavity contains the teeth and alveolar ridges of the mandible and maxilla, the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, and the hard palate. It is also the site of the orifices of the ducts of the major salivary glands ( ▶ Fig. 18.1).

Fig. 18.1 Anatomy of the oral cavity and oropharynx.

The oropharynx begins at the anterior tonsillar pillars and extends to the hyoid bone inferiorly and to the level of the soft palate superiorly, where the nasopharynx begins. The tonsils, soft palate, posterior one-third of the tongue (base of tongue), and suprahyoid epiglottis are located in the oropharynx. The nasopharynx is bounded anteriorly by the choana and contains the tori tubarii and the adenoids. (The choana is the junction between the nasal cavity and nasopharynx.) The hypopharynx begins below the hyoid bone and includes the piriform sinuses and the postcricoid region.

18.2.2 Function

The oral cavity, pharynx, and nasal cavities serve many functions. The oral cavity, oropharynx, and hypopharynx are the entrance to the digestive tract. The pharynx, nasal cavities, and oral cavity form the resonator of the voice. Abnormalities of these structures may affect speech or swallowing.

18.2.3 Choanal Atresia

In general, congenital problems are a result of either failure of a closed structure to open (e.g., choanal atresia) or the failure of a structure to close properly (e.g., cleft palate). The nasal placode is a thickening of the ectoderm (outer surface) of the face, which develops during the third or fourth week of gestation and invaginates, creating two nasal pits a week later. 4 The forming nasal cavity remains separate from the pharynx at the bucconasal membrane. This membrane usually ruptures at about the eighth week of gestation. Failure to rupture leads to choanal atresia, which can be uni- or bilateral ( ▶ Fig. 18.2).

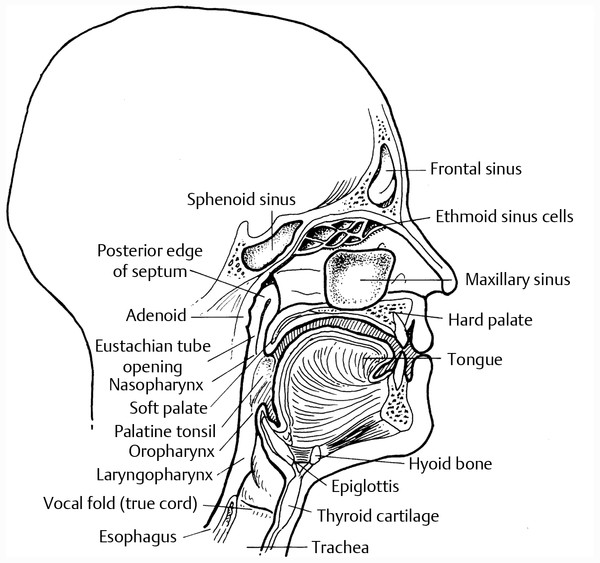

Fig. 18.2 Lateral view of the upper aerodigestive tract.

Infants are obligate nasal breathers: they must breathe through their noses. The high position of the infant’s larynx, which causes them to breathe through the nose, also enables them to eat and breathe simultaneously. Bilateral choanal atresia presents at birth with symptoms of choking, inability to nurse, and cyanosis. The diagnosis is made by unsuccessfully attempting to pass red rubber catheters through the nose to the pharynx. Various devices, the simplest of which is a baby bottle nipple with the end cut off (McGovern Nipple), are used to allow the infant to breathe through the mouth. Feeding tubes are sometimes necessary initially. Tracheotomy rarely is needed. By 2 or 3 weeks of age, the infant has often learned to breathe orally.

Surgical opening of the atresia is often done at 10 weeks of age. There are several different techniques for repairing choanal atresia, including transnasal and transoral/transpalatal approaches.

Unilateral choanal atresia is less obvious and is often not diagnosed for months to years. Unilateral chronic nasal discharge is often the only symptom. Hyponasal speech is also not uncommon. Choanal atresia may be associated with other congenital anomalies.

18.2.4 Cleft Lip and Palate

The palate is formed by the fusion of several structures, including the frontal nasal process and the palatal shelves of the maxilla, whereas the upper lip is a fusion of the lateral and medial nasal processes. This process takes place around the tenth week of gestation. Failure of proper fusion or improper breakdown of epithelial bridges may result in a variety of abnormalities of the upper lip, nose, or palate.

The least severe deformity is diastasis of the musculature of the soft palate or a submucosal cleft palate. The patient may present with velopharyngeal insufficiency with hypernasal speech and nasal regurgitation of fluids. Speech therapy often benefits patients with mild cases. For more severe cases, surgical procedures are available to reestablish the muscular integrity of the soft palate, to augment the posterior pharyngeal wall, or to partially close the nasopharynx with flaps.

The most severe clefting is bilateral cleft lip and a complete cleft of the hard and soft palates. Various combinations of cleft lip and palate can exist, resulting in different types of feeding, speech, and cosmetic problems. Feeding difficulties in cleft palate are primarily due to the infant’s inability to generate negative pressure to suck, because air leaks through the cleft. Food in the oral cavity and oropharynx also refluxes freely into the nasopharynx and nasal cavity. Unrepaired cleft palate also results in a severely hypernasal voice, which may result in unintelligible speech. Repair of the lip is usually done when the child has fulfilled the rule of tens (i.e., 10 weeks old, 10 pounds, and hemoglobin of 10 g). The palate is repaired somewhat later, between 12 and 24 months of age. 5

Abnormalities of the musculature of the soft palate often lead to eustachian tube dysfunction due to the relationship of the tensor veli palatini and levator palatini muscles to the tori tubarii, the openings of the eustachian tubes. Middle ear effusions and sometimes more extensive ear disease are often seen in cleft palate patients. Placement of tympanostomy tubes to prevent problems from developing is advisable.

Velopharyngeal insufficiency can also be the result of lack of vagal innervation of the soft palate. This may be seen in cerebral palsy, following poliomyelitis, or with Arnold-Chiari malformation. A prosthesis that lifts the soft palate is often very effective. Bilateral lesions of the vagus nerve are extremely unlikely, whereas resection of a skull base tumor can often result in a unilateral vagal palsy with unilateral weakness of the soft palate. Surgical attachment of the paralyzed side to the posterior nasopharyngeal wall relieves the patients of their symptoms quite well. 6

18.2.5 Adenotonsillar Hypertrophy

The adenoids and palatine tonsils (commonly known as the tonsils) are part of the ring of lymphatic tissue in the pharynx, which, with the lingual tonsils, make up Waldeyer’s ring. This ring of tissue is the first part of the lymphatic system to encounter foreign substances that enter the body through the nose or mouth, and it is thought to sensitize the immune system to invaders. Problems with the tonsils and adenoids can occur when they hypertrophy and obstruct the naso- and oropharynx or they become chronically infected with bacteria, often group A, β–hemolytic streptococci. Hypertrophy causes hyponasal voice, nasal obstruction, snoring, chronic mouth breathing, and occasionally obstructive sleep apnea. Chronic tonsillitis causes chronic sore throat, odynophagia, and, often, halitosis. If the tonsils and adenoids do not shrink with age or remain symptomatic despite medical intervention, surgical excision of the tonsils and/or adenoids usually resolves the problems. Removal of the adenoids, however, can lead to velopharyngeal insufficiency and associated symptoms of nasal regurgitation and hypernasal voice. This usually occurs only transiently, lasting days to a few weeks, in a small number of patients (less than 5%) and is very rarely permanent (less than 1%). The permanent cases are usually seen only in children with a short palate or unrecognized submucous cleft palate. Treatment includes a palatal lift prosthesis or surgery to lengthen the palate or to adhere it to the posterior pharyngeal wall.

18.2.6 Tongue Disorders

Most disorders that affect the tongue are related to changes of the mucosa, changes that can occur in any of the oral mucosa, including hyperkeratosis, dysplasia, and atrophy. Most mucosal abnormalities seen are very nonspecific and of little clinical significance. Many need to be biopsied to rule out carcinoma, but otherwise require no therapy.

Lack of sense of taste is usually due to the loss of the sense of smell, not an actual abnormality of the taste apparatus. However, various systemic illnesses and medications can diminish the overall sense of taste. Decreased taste or numbness in a specific part of the tongue should alert the clinician to the possibility of a lesion of the nerve (lingual or glossopharyngeal) supplying sensation to that portion of the tongue.

Motor function of the tongue is integral in chewing, manipulating a food bolus, swallowing, and articulating speech. Interruption of the motor innervation to the tongue is usually the result of stroke or other significant intracranial event or surgical trauma in the neck or floor of the mouth. Rarely, a malignant neoplasm of the skull base or submandibular gland presents with unilateral tongue palsy. Fortunately, the tongue is able to accommodate unilateral hypoglossal nerve palsy well, with very little long-term dysarthria or dysphagia, provided there are no other cranial nerve palsies.

18.2.7 Salivary Gland Disorders

The oral cavity is the site of the openings of the ducts of the major salivary glands and the site of many minor salivary glands. The three pairs of major salivary glands are the parotid glands, located anterior to the ear and superficial to the angle of the mandible, the submandibular glands, just inferior and medial to the body of the mandible, and the sublingual glands, inferior to the anterior tongue. Each gland produces saliva of slightly different composition when stimulated by the autonomic nervous system. Saliva lubricates the mouth, and salivary enzymes initiate digestion of food. Dry mouth (xerostomia) results when the salivary glands cease to function properly. A chronically dry mouth is very uncomfortable, makes eating more difficult, and can lead to dental disease. Xerostomia can be due to simple problems, such as inadequate water intake and dehydration, or to more complex autoimmune diseases, such as Sjögren’s syndrome, in which the tissue ceases to function. A common cause of xerostomia is medication that alters the autonomic input to the glands, such as antihistamines and antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs. Caffeine and alcohol have similar effects. Xerostomia is also a common side effect of radiation therapy to the oral cavity or oropharynx. Treatment first involves identifying and treating the etiology, followed by the use of oral lubricants and medications that directly stimulate the salivary glands. Chronic xerostomia can lead to dental disease.

18.2.8 Infections of the Oral Cavity, Oropharynx, Nasopharynx, and Salivary Glands

Infections can occur in many different structures within and around the oral cavity and oropharynx. They can be viral, bacterial, and fungal or due to mycobacteria, some of which cause tuberculosis. The most common infection is viral pharyngitis, which causes sore throat and odynophagia (painful swallowing). The tonsils may be involved and swell enough to threaten the airway. Less common viruses, such as the herpes virus, may cause painful and infectious vesicular sores on the lips and in the mouth. Aphthous ulcers, commonly known as canker sores, are thought to be due to local trauma and possibly a nonherpetic viral infection. They are very painful and usually last about 7 days, but they are not contagious. Pharyngitis and tonsillitis may also be caused by bacteria. Infection by group A β–hemolytic streptococci (strep throat) is the most feared, due to its potential systemic effects, such as rheumatic fever, rheumatic heart disease, and kidney disease (acute glomerulonephritis).

The salivary glands are also prone to infection. This can be viral, as in mumps, which affects the parotid glands, or suppurative sialoadenitis, in which bacteria, usually Staphylococcus aureus, may infect any of the salivary glands. Stones within the ducts or glands themselves (sialolithiasis) make bacterial sialoadenitis more likely, as do dehydration and other causes of xerostomia discussed above.

Treatment of the infectious processes varies according to the etiology and structure involved. Hydration, analgesics, and antipyretics relieve most symptoms. Some viruses may be treated with specific antiviral agents (e.g., acyclovir and famvir are effective against herpes simplex), whereas most other viruses are not affected by antiviral agents. Bacterial infections are treated with antibiotics. Occasionally, a bacterial infection progresses to an abscess that does not respond to antibiotic therapy. Surgical drainage is then required, and it can be done through either the mouth or the neck. Severe, life-threatening infections can develop if the abscess extends into the neck, where it can involve the great vessels or cause enough swelling to obstruct the airway. Incision and drainage of a deep neck abscess and sometimes tracheotomy are performed emergently in those cases.

18.2.9 Neoplasms of the Oral Cavity, Oropharynx, and Salivary Glands

The most common malignant tumor of the oral cavity and oropharynx is squamous cell carcinoma, which is usually caused by tobacco use or, to a lesser extent, alcohol abuse. There is an increasing incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx in nonsmokers caused by human papillomavirus. Fortunately, these tumors have a better prognosis than those caused by smoking and drinking alcohol (see detailed discussion in Chapter 13).

Common benign tumors include papillomas, which are caused by the human papillomavirus, and fibromas, caused by trauma. Simple excision is usually curative.

Tumors may also develop within the salivary glands. If they are either benign or malignant but are diagnosed early, excision of the gland may effect a cure. Although excision is relatively straightforward for the submandibular glands, it is much more complex for the parotid glands. The facial nerve leaves the skull base just inferior to the ear and courses through the substance of the parotid gland en route to the muscles of the face, which it innervates. Any surgery of the parotid gland must begin with identification and careful dissection of the facial nerve to avoid nerve injury, which could result in unilateral complete facial paralysis, with inability to close the eye and the lips and obvious cosmetic deformity.

18.2.10 Trauma to the Oral Cavity

Trauma to the oral cavity may be blunt or penetrating, with the former more common. Motor vehicle accidents and assaults are responsible for most blunt injuries that result in mandibular fractures. Treatment of mandibular fractures entails reestablishing normal occlusion, which may be achieved with a variety of techniques, including long-term (6 weeks) maxillomandibular fixation (MMF, wiring the jaws together) alone, MMF and wiring or plating of the fractures, or screwing and compression plating of the fractures with immediate release of MMF. The technique chosen depends on the site and direction of the fracture, the presence or absence of teeth, and the surgeon’s experience. When a mandibular fracture is combined with other facial injuries, the repair becomes more complex and reestablishment of normal occlusion is less certain.

Penetrating injuries to the oral cavity and pharynx range from hard and soft palate lacerations, which result from children falling down on objects in their mouths, such as toy trumpets or popsicle sticks, to devastating shotgun injuries sustained in unsuccessful suicide attempts. The former warrants evaluation due to the proximity of the carotid artery to the lateral pharyngeal wall and possible damage to that structure. The latter injury requires many procedures first to salvage as much tissue as possible and then to reconstruct the face.

18.2.11 Sleep Disorders

Many conditions can affect sleep. Probably the most common sleep-related problem is snoring, which represents turbulent airflow during sleep and affects about 50% of males and 30% of females. Snoring is more common as people age and is more common in people who are overweight. Snoring tends to worsen after alcohol intake and when the persons lies flat on the back. Snoring is a sign of an obstruction, which may affect one’s ability to sleep.

Although snoring is often perceived as a problem only for the snorer’s bed partner, it may be a sign of the more serious condition known as obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), in which breathing stops (apnea) for periods of time during sleep. Patients with OSAS commonly complain of excessive daytime sleepiness, headaches, and chronic fatigue. The condition can lead to high blood pressure, cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, sudden death, and automobile accidents due to falling asleep while driving. 7

Apnea may be due to the central nervous system not initiating a breath, or, more commonly, a blockage developing somewhere in the throat or nasal passages, stopping the flow of air. Various abnormalities of the facial structures and throat can cause sleep apnea by blocking breathing through the nose or throat, or by causing the tongue to fall back into the throat. Large tonsils, a long and floppy soft palate, a large tongue, or a short mandible may promote this condition. If sleep apnea is suspected, the patient should undergo polysomnography, or sleep study, which involves either spending a night in the sleep laboratory or use of home-based, mobile sleep study equipment and services. While the patient sleeps, measurements are taken of eye movements, brain wave activity (electroencephalography, EEG), heart activity, breathing activity, and oxygen saturation (level of oxygen in blood). Based on the findings of this examination, the patient is diagnosed with either a snoring disorder only, or mild, moderate, or severe sleep apnea.

There are various treatments for sleep apnea. In patients who are overweight, weight loss is extremely important and occasionally is enough to relieve the patient’s symptoms. Exercise and regimented sleep-wake cycles are also helpful.

The goal of treatment is to keep the airway open while the patient is sleeping. This can be done with a nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device, in which the patient is fitted with a mask over the nose providing a constant flow of air through the nose to prevent collapse of the throat while inhaling. Although particularly effective, CPAP is sometimes poorly tolerated. Other options include oral airways, which are devices placed in the mouth that hold the tongue and jaw forward to keep the tongue from falling back and obstructing the airway. Nasal airway devices may be helpful in some patients. The oral and nasal airways are not particularly comfortable or well tolerated; therefore, they are often abandoned by the patient, who continues to suffer from the effects of sleep apnea.

Surgical procedures may permanently open the breathing passageways without the use of devices. For extremely severe sleep apnea, a tracheotomy may be done. This is the ultimate surgical procedure for this disease and works 100% of the time, but it does require long-term care of the tracheostomy tube. Most patients do not desire or require this procedure.

Other surgical procedures are aimed at improving the airway in the nose. Several operations have been developed to open the airway at the level of the throat, the most common area of obstruction. The most popular of these is tonsillectomy and uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP). In this procedure, the surgeon removes the tonsils, which are usually contributing to the problem, and excess tissue from the soft palate (including the uvula) and pharyngeal walls. UPPP creates more room in the throat and prevents collapse of the tissues while the patient is sleeping. A staged, laser-assisted version of the procedure can now be performed on an outpatient basis without general anesthesia. Procedures have also been developed to pull the jaw forward, primarily to pull the tongue forward, preventing it from falling back and blocking the airway.

Various surgical approaches aimed at decreasing obstruction at the level of the base of the tongue (retrolingual approaches) have also been developed. They include removal of the lingual tonsils, portions of the tongue itself, and sometimes a portion of the epiglottis, if it is determined to be contributing to the obstruction. The advent of the surgical robot (transoral robotic surgery [TORS]) has made surgery in this difficult-to-access region much more feasible.

Sleep nasoendoscopy (SNE) or drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) is a technique in which endoscopy of the airway is done as the patient sleeps under anesthesia. This may improve the surgeon’s ability to determine the areas of obstruction more accurately, so the surgery can be focused on those specific regions, thereby decreasing the potential side effects and complications of the surgery and making it more effective.

These procedures alter the shape and function of the pharynx and can potentially affect the voice. In most cases, if there is a change, it is a positive one, with decreased hyponasality in patients who have had adenoids removed or a deviated nasal septum straightened, or a less muffled voice after UPPP in a patient with large tonsils. A potential complication of UPPP, however, is velopharyngeal insufficiency. It occurs transiently in up to 15% of patients and permanently in less than 1% of cases.

A variety of procedures have been developed to treat primary snoring. All of them are aimed at stiffening and/or shortening the soft palate. They include injection snoreplasty (injection of a sclerosing agent into the anterior surface of the soft palate) and somnoplasty (heating the muscles of the soft palate with a radiofrequency instrument).

18.3 Nasal and Sinus Disorders

18.3.1 Function of the Nasal Cavities and Paranasal Sinuses

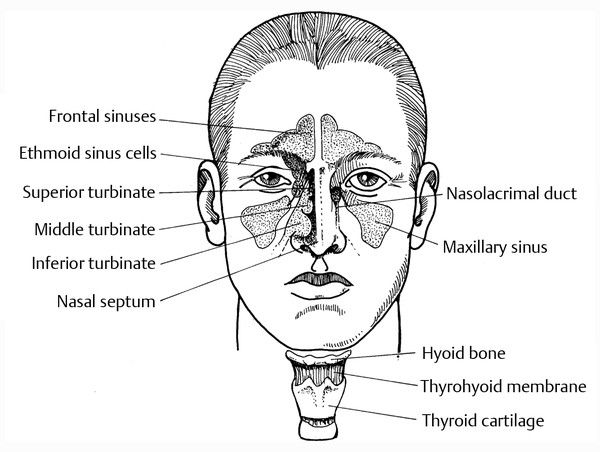

The nasal cavities humidify inspired air, filter out foreign matter, provide passage of outside air to the olfactory nerves (smell), and act as a resonator for the voice. The nose is the preferred route of breathing during most activity except during strenuous exercise, when the mouth is usually open. The function of the paranasal sinuses is unclear. One theory is that the sinuses serve as buffers/bumpers for trauma to the head and eyes. Another is that hollow sinuses make the head lighter ( ▶ Fig. 18.3).

Fig. 18.3 Coronal view of nasal and sinus cavities.

18.3.2 Disorders of the Nasal Cavities and Paranasal Sinuses

The most common nasal complaint is obstruction. Congenital problems, such as choanal atresia, and nasopharyngeal disease, such as adenoid hypertrophy, can cause obstruction, as can acquired obstructing lesions of the nasal cavities themselves. The nasal septum should be a straight, relatively thin, flat, midline structure, but it can become deviated as a person ages, obstructing (partially or completely) either one or both sides of the nose. Trauma to the nose can also cause deflection of the nasal septum or nasal bones. Benign masses, such as polyps or papillomas, as well as malignancies, often also present with nasal obstruction, usually unilateral. Besides the obvious symptom of impaired nasal breathing, patients often complain of decreased sense of smell, hyponasal speech, dry throat (especially in the morning), and snoring. Tumors may also cause pain and bleeding, and more advanced cases can cause anesthesia of the face or eye symptoms. The inferior turbinates are responsible for providing humidity to inspired air and catching foreign substances in the mucus blanket on the mucosal surface. They can swell excessively, however, with allergic rhinitis or a viral upper respiratory tract infection, or they can simply grow for no apparent reason. Enlargement of the inferior turbinates also results in nasal obstruction.

Nasal obstruction may improve with medical therapy aimed at reducing swelling of the mucosal lining of the nose, such as oral decongestants, antihistamines (if allergy is a cause), steroid sprays, and humidification. When medical treatment fails, surgery is often curative. Straightening of the septum (septoplasty) and reconstruction of the entire nose (septorhinoplasty) are very effective procedures with few complications. Cauterizing the inferior turbinates, which leads to scarring and less ability to swell, and fracturing the turbinates and pushing them laterally also improve the airway with minimal morbidity. Sometimes a portion of the inferior turbinate is removed or submucosal tissue is removed. Removing the entire structure can cause excessive drying and crusting in the nasal cavity and is discouraged. Removal of benign lesions, such as polypectomy, is also relatively straightforward, although polyps have a tendency to recur.

Epistaxis

Bleeding from the nose (epistaxis) is another fairly common problem. Most epistaxis originates from small vessels located on the anterior septum, and episodes are brief, relatively mild, easy-to-control bleeding. Occasionally, epistaxis originates from the posterior nasal cavity or nasopharynx, is much harder to control, and may possibly be life-threatening. Nasal packing or cauterizing or ligating the bleeding vessels will usually control the bleeding. Epistaxis may also be a sign of a nasal or sinus neoplasm.

Rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis is a common cause of intermittent nasal obstruction. Other symptoms include clear, watery rhinorrhea, sneezing, and itchy nose and eyes. The symptoms occur in the presence of specific allergens present during certain seasons (e.g., pollens, fungi) or in certain locations (e.g., dust mite, animal dander). Avoidance or elimination of the allergens provides definitive treatment, although this is frequently difficult. Few patients will part with their pets, for example. Antihistamines, steroid nasal sprays, and cromolyn nasal sprays (cromolyn prevents the mast cell from releasing histamine) may be necessary. Usually only one of these classes of medications is necessary at any one time. Antihistamines have the disadvantage of sometimes causing sedation and of excessively drying the mouth and pharynx, which can be a problem for professional voice users. Desensitization injections, commonly known as allergy shots, frequently succeed in making the person less sensitive to the allergens.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is an infection of one or more of the eight paranasal sinus cavities. It usually follows a viral upper respiratory infection or an exacerbation of allergic rhinitis. These conditions cause swelling of the nasal mucosa, including the mucosa at the naturally small openings of the sinuses. Anatomical abnormalities and polyps may also block the sinus ostia. Blockage of the openings creates a closed cavity, which is an excellent environment for bacterial colonization and growth; bacteria are the most common pathogens in sinusitis. Symptoms of acute sinusitis include purulent nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, facial pain and pressure, fever, and occasionally headache. Treatment is aimed at opening the closed sinus cavities and eradicating the bacteria. Oral and topical nasal spray decongestants, saline nasal rinses, analgesics, rest, and antibiotics are crucial. Most acute episodes of sinusitis in immunocompetent individuals clear with one course of medical therapy.

Potential, but rare, complications of acute sinusitis include spread of the infection to the orbit, with possible injury to the eye, or intracranially, with possible meningitis, brain abscess, or cavernous sinus thrombosis. These complications usually require surgical intervention to open up and drain the affected sinus and adjacent infected area, such as the orbit.

Chronic sinusitis is quite different from the acute disease, although acute exacerbations may occur in a patient with chronic disease. The common symptoms of chronic sinusitis include chronic nasal and postnasal discharge, which is usually thick mucoid material, and varying degrees of nasal obstruction, pressure, or a heavy feeling in the face and head. Facial pain and headaches rarely occur in chronic sinusitis and fever is also uncommon. Patients are treated in a similar manner to those with acute sinusitis, but the duration of therapy is longer. Antibiotics are prescribed for 3 weeks or longer; nasal steroid sprays and oral decongestants or antihistamines (if allergy is present) are taken indefinitely. A course of oral steroids is also indicated. Nasal endoscopy helps to determine whether small polyps or other lesions are obstructing the sinus ostia. A CT scan is the test of choice for assessing location and extent of disease. It often shows obstruction of the ostiomeatal complex, which is the common path of drainage for the frontal, anterior ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses. It may also show thickening of the mucosal lining of the sinuses, a sign of chronic sinusitis. A patient who has severe enough symptoms and fails medical therapy is a candidate for surgery. Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) has greatly decreased the morbidity associated with sinus surgery and is the preferred technique. 8 With the increased ability to see the anatomy during ESS, more precise and more thorough removal of diseased tissue can be performed without the need for external incisions. Success rates are about 85%. 9 Nasal polyps are often seen in patients with chronic sinusitis. They are removed during ESS and are thought to recur less often after this procedure than after a simple polypectomy. In revision cases, which are often difficult, computer-based navigation systems increase safety.

Nasal Masses

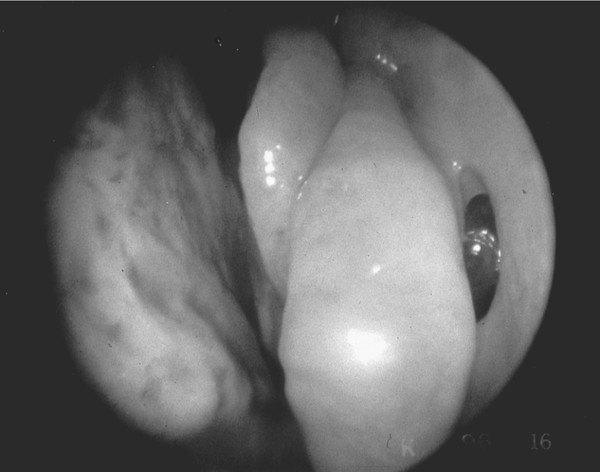

The most common benign nasal mass is the inflammatory polyp, although it is not considered a true neoplasm ( ▶ Fig. 18.4). As discussed above, polyps usually cause nasal obstruction and are frequently associated with allergic rhinitis or chronic sinusitis. In children, the presence of nasal polyps suggests the possibility of previously undiagnosed cystic fibrosis. Removal of nasal polyps involves simple polypectomy or more extensive sinus surgery, depending on symptoms and other findings. Squamous papillomas are the most common true neoplasms in the nose. They are benign and are usually cured with simple excision.

Fig. 18.4 Large polyp extending from the left middle meatus into the nose. The polyps caused nasal obstruction and chronic rhinosinusitis. The right nostril was completely obstructed by polyps.

Inverted papilloma is less common and also benign. It can, however, be very aggressive and is capable of eroding through adjacent bony structures into the orbit or intracranially. Removal of these lesions requires excision of the tumor with a wide margin of normal tissue. Because papillomas are found most commonly on the lateral nasal wall, they are usually treated with a medial maxillectomy, which removes the entire lateral nasal wall, ethmoid sinus, and medial wall of the maxilla. With a less extensive operation, recurrence is common. With advances in ESS, recurrent papillomas are usually removed endoscopically.

18.3.3 Facial Pain

Pain can result from many different disease processes. The most common causes of facial pain are trauma, sinusitis, and dental disease. The history suggests the diagnosis, which is usually confirmed with the physical findings. With appropriate treatment and resolution of the disease, the pain also abates. Sometimes the cause of the pain is not apparent or the pain does not resolve with the other symptoms.

As discussed above, acute (not chronic) sinusitis is often painful. Tenderness is elicited over the maxillary or frontal sinuses if they are involved. Inflammation of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses can cause pain at the top of the head and occiput, respectively; however, the pain is usually not an isolated symptom, but is associated with other signs of sinusitis.

The trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) supplies sensation to the face. The first division (ophthalmic) supplies the forehead, eyebrows, and eyes. The second division (infraorbital) supplies the cheek, nose, and upper lip and gums. The third division (mandibular) supplies the ear, mouth, jaw, tongue, lower lip, and submandibular region. When pain is located in a very specific nerve distribution area, lesions involving that nerve must be considered. Tumors involving the nerve usually cause other symptoms, but pain may be the only complaint, and presence of a tumor at the base of the skull or in the face must be ruled out. When the work-up is negative, the diagnosis may be one of many types of neuralgia, which is a pain originating within the sensory nerve itself. Treatment is medical or, in some cases, surgical.

Otalgia (ear pain) can be caused by many different conditions of the ear itself, including trauma, infection, foreign body, tumor, and even cerumen impaction, or it can be referred pain. The external ear canal and auricle receive sensory innervation from branches of four different cranial nerves: the fifth (trigeminal), seventh (facial), ninth (glossopharyngeal), and tenth (vagus). These nerves also supply various other parts of the head and neck, and even the thorax and abdomen in the case of the tenth nerve. Inflammation of another part of these nerves, for example, inflammation of the vagus nerve from a tumor of the larynx or hypopharynx, will often cause otalgia along with the local symptoms. More common conditions, such as tonsillitis or an aphthous ulcer of the soft palate, also cause referred otalgia.

Many craniomandibular disorders include head and neck pain among their different and varied symptoms. Many of these conditions are related to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and surrounding structures. Internal abnormalities of the TMJ may cause local pain, otalgia, trismus, sounds within the joint during mandibular movement, and change in occlusion. 10 Extracapsular craniomandibular disorders are also known as myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome and are thought to be due to an abnormal relationship of the dental apparatus, the TMJs, and the neuromuscular system. 10 Symptoms include pains that do not seem related to the TMJ, headaches, muffled ears and other otologic symptoms, and various other vague facial, dental, and neck symptoms. The work-up is first aimed at finding and correcting the underlying cause of the symptoms, such as an intracapsular lesion of the TMJ or dental malocclusion. This may require simple measures, such as a bite plane to align the occlusion at night and prevent bruxism, or may require surgery of the TMJ itself. Other treatments include transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) to control muscle spasms and relieve pain.

18.4 Anatomy of the Larynx

To understand the anatomy of the larynx, it is imperative to realize that the larynx is not an anatomical site unto itself. Much of the function of the larynx is dependent on the structures that are attached to, and integrated with, the larynx. These include the muscles and soft tissues of the neck, the trachea, and the esophagus; the hyoid and mandibular bones; and the muscles of the tongue. Functionally, the larynx depends on the integration of activities with the nervous system, both afferent and efferent impulses, and coordination of activities via the central nervous system and the spinal cord. It is often simplest to think of the larynx in relationship to its four major tissue types: cartilages, muscles, nerves, and blood vessels.

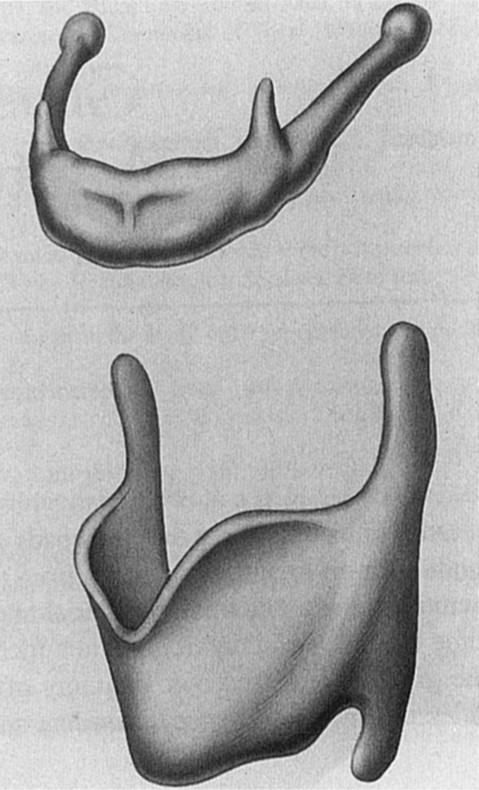

There are five primary laryngeal cartilages: the thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, epiglottis, and a pair of arytenoid cartilages ( ▶ Fig. 18.5, ▶ Fig. 18.6, ▶ Fig. 18.7). In addition, there are smaller cartilages, the function of which is not perfectly clear. These are the paired cuneiform and corniculate cartilages, which lie in the aryepiglottic folds superior to the arytenoid cartilages. The thyroid cartilage, whose name is derived from the Greek word for shield, is the largest cartilage in the larynx and encompasses the anterior and lateral skeletal structure of the larynx. The cartilage has a superior and inferior cornua to which are attached the thyrohyoid ligament and the cricothyroid ligament, respectively, and bilateral ala. The cartilage also has an oblique line on the ala to which is attached the middle constrictor muscle. This attachment is important for the superior movement of the larynx with swallowing. The anterior thyroid cartilage extends from the thyroid notch to the anterior-inferior cartilage. The angle of the anterior cartilage tends to be more acute in men (90 degrees) than in women (120 degrees), which, along with the larger male laryngeal prominence, makes it more prominent in the neck of men, hence the term Adam’s apple.

Fig. 18.5 Hyoid bone and thyroid cartilage. (Reproduced with permission from Tucker HM. The Larynx. 2nd ed. New York, NY, Thieme; 1993.)

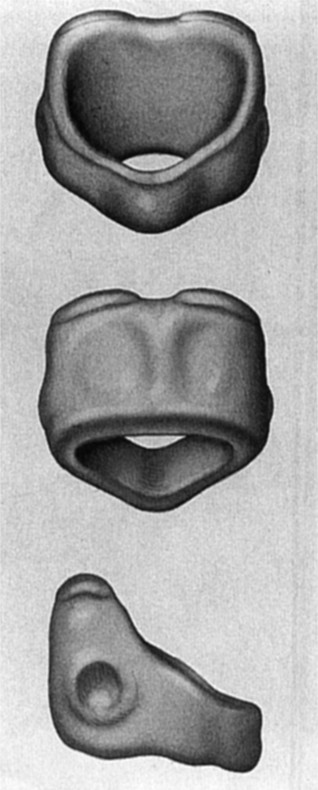

Fig. 18.6 Cricoid cartilage. Top, anterior view; middle, posterior view; bottom, lateral view. (Reproduced with permission from Tucker HM. The Larynx. 2nd ed. New York, NY, Thieme; 1993.)

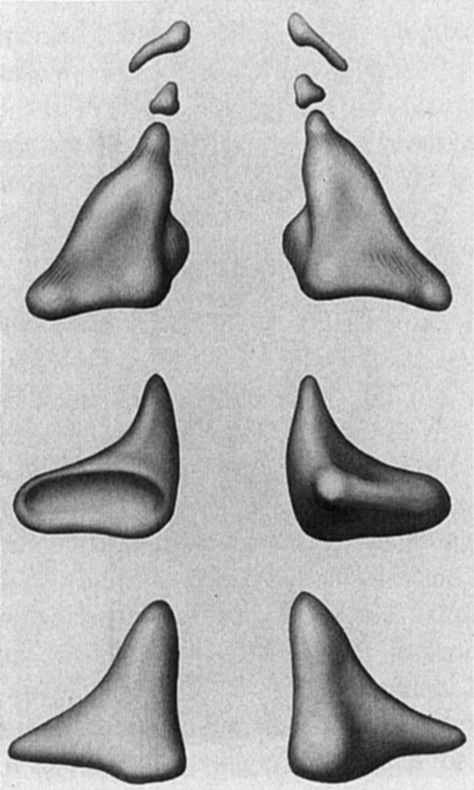

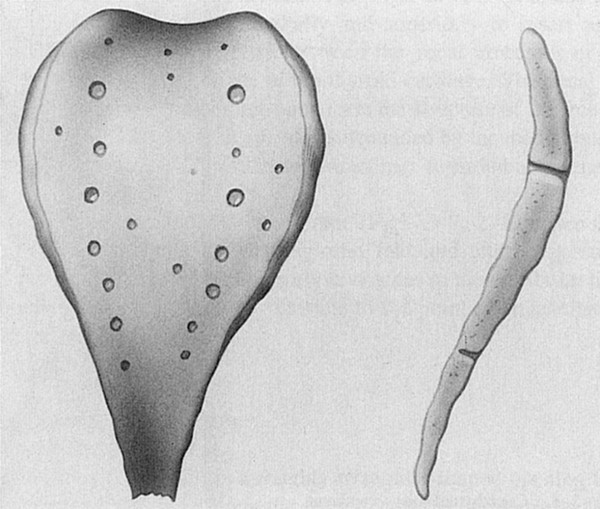

Fig. 18.7 Arytenoid cartilages. Top, posterior view with cuneiform and corniculate cartilages above; middle, inferior view; bottom, anterior view. (Reproduced with permission from Tucker HM. The Larynx. 2nd ed. New York, NY, Thieme; 1993.)

The cricoid cartilage lies just below the thyroid cartilage and is joined to the thyroid cartilage at the cricothyroid joint between the inferior cornua of the thyroid and the lateral joint capsule of the cricoid ( ▶ Fig. 18.8). This joint allows for rotation of the cricoid in relationship to the thyroid cartilages. The cricothyroid membrane attaches the anterolateral aspects of the inferior thyroid to the superior cricoid. The cricoid cartilage is the only complete ring in the upper airway, with the thyroid cartilage and the tracheal rings being open posteriorly. In neonates and infants, this is the narrowest part of the upper airway and is the most common site for upper airway obstruction. Swelling of the tissues of the subglottic region surrounded by the complete ring of fixed cricoid cartilage accounts for the airway obstruction in croup. In older children and adults, the narrowest area is the rima glottis, the space between the free margins of the true vocal folds. The cricoid cartilage is shaped like a signet ring, with the larger face posterior. On the upper surface of the signet portion is the cricoarytenoid joint. This joint is unique in that it allows for both rocking of the arytenoids and also anterior-posterior sliding.

Fig. 18.8 Cricothyroid joint, membrane, and ligament. (a) cricoarytenoid joints; (b) posterior view. (Reproduced with permission from Tucker HM. The Larynx. 2nd ed. New York, NY, Thieme; 1993.)

The arytenoid cartilages are paired cartilages that lie on top of the cricoid cartilage at the cricoarytenoid joint. In addition to the joint, there are three main surfaces (processes) of the arytenoids: the muscular process, posterolaterally, to which is attached the posterior and lateral cricoarytenoid muscles; the vocal process, anteriorly, with the attachment of the vocalis ligament and (thyroarytenoid) muscle; and the posterior surface, where the interarytenoid muscle attaches.

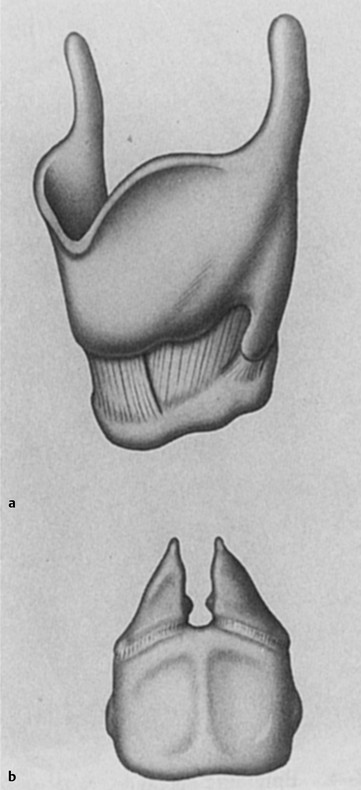

The epiglottis is different from the other cartilages of the larynx in that it is primarily hyaline cartilage ( ▶ Fig. 18.9). This cartilage does not ossify, whereas the other cartilages ossify with age. The epiglottis is attached to the upper, midposterior surface of the thyroid cartilage at the petiole, and laterally with the arytenoids by the aryepiglottic folds. There is an upper, anterior (lingual) and a lower, posterior (laryngeal) surface of the epiglottis. The vallecula is the space between the epiglottis and the base of the tongue.

Fig. 18.9 Epiglottic cartilage. Note perforations. (Reproduced with permission from Tucker HM. The Larynx. 2nd ed. New York, NY, Thieme; 1993.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree