Summary by Karsten Lunze, MD, MPH, DrPH, FAAP

72

Based on “Principles of Addiction Medicine” Chapter by Richard Saitz, MD, MPH, FACP, FASAM

ROUTINE AND PREVENTIVE CARE

Health system resources are increasingly limited, and preventive interventions can have potential adverse effects. Accordingly, preventive care has evolved from a “more-is-better” approach to evidence-based, targeted evaluations based on clinical needs and individual risk factors. The approach to routine and preventative care of patients with substance use disorders presented here follows current national guidelines and recommendations based on the known effectiveness of interventions. Updates of recommendations by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and other evidence-based clinical practice guidelines can be found at http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm.

Medical History

The medical history in a person with addiction includes the categories of assessment employed for all patients (including, but not limited to, current complaints, present illness, allergies, systems review, medication, past medical and surgical history, social and family history), in addition to a thorough alcohol and drug use assessment probing typical past withdrawal symptoms. Questions should address hospitalizations and any medical conditions that might be related to substance use and might not be volunteered by the patient without direct questioning. For persons with addictive disorders, screening for depression and anxiety, assessment of sexual practices, intention to conceive a child, and behavior that might lead to injury (including being alert for signs of interpersonal violence) are particularly important. Such patients should be asked specifically about substance use before operating a motor vehicle, riding with intoxicated drivers, sex without contraception, and sex while intoxicated.

Physical Examination

The physical examination may be complete or, where appropriate, may focus on body systems related to any reported symptoms or clinical observations. It also draws the patient’s attention to possible medical and surgical organ complications from alcohol and substance use.

Tests

Reasonable, inexpensive tests that all patients should undergo at least once include a complete blood count, glucose, liver enzymes, cholesterol, serum creatinine, and urinalysis (to assess for the presence of asymptomatic renal disease).

Of particular importance in heavy drinkers is identifying hypertriglyceridemia, which is associated with and can be a cause of pancreatitis. An unsuspected anemia or pancytopenia can be found in persons with alcohol use disorders or HIV.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Persons with addictive disorders who have been sexually active or who inject drugs should be screened routinely for sexually transmitted diseases including syphilis, HIV, and chlamydia. The serologic test for syphilis (rapid plasma reagin or VDRL) frequently is falsely positive in injection drug users and should be confirmed by direct treponemal tests.

Other Infectious Diseases

Persons with alcohol and other drug use disorders without past known tuberculosis should be screened for asymptomatic infection (using intradermal tuberculin injection), provided a previous test result is not known to have been positive. If screening is positive and provided the radiograph is not consistent with active tuberculosis, prophylactic pharmacotherapy should be considered regardless of age.

To screen for chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis, test injection drug users, those with heavy alcohol use, and persons with multiple sexual partners or high-risk sexual activity for INR, bilirubin, aspartate amino transferase (AST) and alanine amino transferase (ALT), albumin, and AP.

If any of the first three are abnormal, test for hepatitis B (surface antigen and core antibody) and hepatitis C antibody. Previously vaccinated individuals should have the antisurface hepatitis B antibody determined to assess current immunoprotection. Consider testing for immunity to hepatitis A in injection drug users, those who practice anal intercourse, and those who are not from endemic areas.

Cancer Screening and Testing for Other Conditions

Smokers are at higher risk of cervical cancer; thus, cervical cytology (Pap smears) should be performed as recommended by the USPSTF. Breast and colorectal cancer screening should be done as recommended by the USPSTF. Adults over 65 years should receive thyroid function testing and vision and hearing screening. Persons with addictive disorders can have poor diets, inadequate calcium intake, little sun exposure, and minimal intake of milk products; bone mineral density testing and screening for vitamin D deficiency with a 25-hydroxyvitamin D should be considered.

Preventive Counseling

In addition to specific counseling related to addiction, preventive health counseling for these patients should include the following: healthy dietary habits, safe sexual practices and contraception, gun safety, seat belt and helmet use, designated driver, and safe lifting to prevent low back injury. Additionally, injection drug users should be educated about sterile injection practices. Patients should be encouraged to engage in regular primary and preventive health care with a primary care physician in addition to their addiction specialty care, and mental health care should be offered when appropriate.

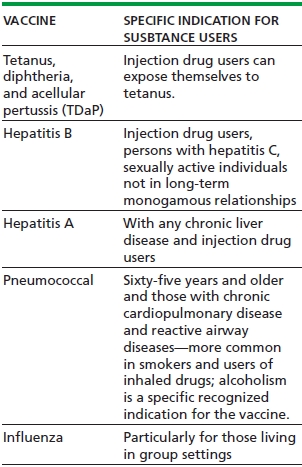

Immunizations

Immunizations for adults should follow CDC guidelines (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/) (Table 72-1).

TABLE 72-1. IMMUNIZATONS

Other recommended vaccines including varicella, zoster, and human papilloma virus can be considered on an individual basis. When childhood vaccinations are unknown, consideration should be given to a primary series for routine vaccination. Many adults will have immunity to these diseases, but, if unknown, testing is warranted, given that many persons with addictive disorders may be in group living situations, sometimes with children and young adults, which places them at higher risks for measles and varicella infections.

Preventive Medication

The potential benefit of a reduction in cardiovascular risk (can be calculated using tools like http://cvdrisk.nhlbi.nih.gov/) should be weighed against the potential harm of an increase in risk for gastrointestinal hemorrhage (in older people, those with gastrointestinal pain, ulcers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, liver disease, or alcoholic gastritis). The USPSTF recommends the use of aspirin for men aged 45 to 79 years when the potential benefit of a reduction in myocardial infarction outweighs the potential harm of an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage and for women aged 55 to 79 years when the potential benefit of a reduction in ischemic stroke outweighs the potential harm of an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Folate and Other Vitamins and Minerals

As folate deficiency is common in patients with alcohol use disorder, women of childbearing age should take 400 μg daily to prevent fetal neural tube defects. Recommend daily multivitamin for people with alcohol use disorders and those with deficient diets as they are at risk of thiamine, vitamin D, pyridoxine, niacin, riboflavin, zinc, and folic acid deficiency. In people with alcohol use disorders, encourage use of foods with a high magnesium content (such as peanuts) or a magnesium supplement (magnesium oxide tablets or magnesium hydroxide-containing antacids) to prevent magnesium deficiency, which is common in this population.

Osteoporosis

Risks for osteoporosis are higher in people with alcohol use disorders and other addicted persons. The interaction between estrogen and alcohol on breast cancer is not clear, and the side effects of hormonal medications in people who drink heavily and those with liver disease are not well characterized. All adults with insufficient intake should be supplemented for calcium and vitamin D, with dosing adjusted for age and gender.

CARE DURING HOSPITALIZATION

Withdrawal

In patients with a history of moderate-to-severe alcohol use disorder and recent regular heavy use, withdrawal should be anticipated. Opiate and other drug withdrawal should be identified and managed pharmacologically, both for patient comfort and to prevent complications of the medical disorder for which the patient was hospitalized. In addition to providing comfort and helping to prevent the more serious complications of withdrawal, specific treatment of withdrawal controls the autonomic symptoms that can worsen a patient’s medical condition and helps the patient cooperate with treatment for the medical condition that prompted hospitalization.

Pain

Pain management often becomes a challenge during medical hospitalization of addicted patients. Providers may fear that controlling pain with opioids when a patient is addicted to them will worsen addiction. Patients with addictive disorders, including those on opioid agonist treatment, usually are very tolerant to the substance they use. Therefore, pain control can be achieved only with substantially higher doses of opioids. Once a dose is determined, pain medications should be given on a regular schedule rather than as needed, to avoid making the patient demand medication to relieve uncontrolled symptoms.

Comorbidities

Finally, while patients are hospitalized, several comorbidities should be considered. As psychiatric comorbidity is common, attention to behavioral issues is important. Patients should be assured that their medical, psychiatric, and addiction-related symptoms and pain will be attended to. Screening for coexisting medical disorders (such as HIV, hepatitis, and tuberculosis) during a medical hospitalization should be considered because the acute care setting may provide the only medical care received by the patient. A patient’s readiness to hear and handle the results and to arranging follow-up medical care for the condition should be taken into consideration.

MEDICAL CONSEQUENCES OF ALCOHOL, TOBACCO, AND OTHER DRUG USE

Medical consequences of addiction may be due to drug-specific effects, methods of administration, contaminants in or vehicles for drugs used, behavioral habits associated with substance use, or common comorbidities.

Alcohol

Alcohol affects almost any organ system of the body. Women are more susceptible to many of the effects of alcohol at lower doses because of first-pass metabolism of alcohol and lower average body weight. While low-risk drinking may have some beneficial effects for certain individuals, more than one standard drink per day for women and two for men increase the risk of mortality and morbidity.

Cardiovascular Consequences

Hypertension can occur as a transient symptom of withdrawal. It can become chronic even at low levels of regular alcohol consumption and with heavy drinking (about two or more standard drinks per day). Chronic heavy drinking can lead to alcoholic cardiomyopathy (clinically presenting identical to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy) and congestive heart failure and its potential complications, such as left ventricular thrombosis and embolic stroke. Treatment consists of alcohol abstinence and standard therapy for congestive heart failure and eventual complications.

Rhythm disturbances, particularly supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, can occur as a consequence of alcohol use or withdrawal. Referred to as “holiday heart” when following excessive alcohol consumption, these usually resolve spontaneously or after treatment for withdrawal (with benzodiazepines and β-blockers) and abstinence.

The association between lower levels of drinking (fewer than two standard drinks per day) and fewer cardiovascular events and decreased mortality in men (but not in average-risk women) remains controversial. The epidemiologic findings of benefit for moderate drinking might be confounded by differences that remain unaccounted for, such as social factors. Studies have suggested that if there is a benefit, it may be most pronounced in patients who have the same alcohol dehydrogenase genotype that may predispose them to alcohol use disorder. Nondrinkers should certainly not begin to drink for cardiovascular benefit.

Liver and Gastrointestinal Consequences

In alcoholic hepatitis, AST usually is higher than ALT. Higher ALT concentration suggests another or a concomitant etiology, such as hepatitis C. Though steatohepatitis is best diagnosed by liver biopsy, clinically, it is often diagnosed when serology for hepatitis B and C is negative, the abnormality persists with abstinence, and an ultrasound examination is consistent with the diagnosis. Classic alcoholic hepatitis presents with fever, leukocytosis, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, and elevations of the AST concentration out of proportion to ALT elevations. Management consists of abstinence from alcohol as well as supportive care, with attention to fluid and electrolyte balance, vitamin K for coagulopathy, clotting factor replacement when there is active bleeding and coagulopathy, and attention to volume and mental status.

Cirrhosis, and associated hypoalbuminemia, coagulopathy, and hyperbilirubinemia, can develop in chronic alcohol users either as a consequence of hepatitis C, recurrent alcoholic hepatitis or, chronic use of more than two to three standard drinks per day (although it is more common in heavy alcohol use). Hepatocellular carcinoma can occur, particularly when hepatitis C is present. Surgical treatment may be hampered by complications of cirrhosis, which include hepatic encephalopathy, esophageal or gastric variceal bleeding, ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, volume overload and edema, and hepatorenal syndrome. End-stage liver disease of many etiologies can be addressed with liver transplantation with similar survival in those transplanted because of alcoholic liver disease compared with other causes of liver failure. Most transplant recipients do not return to drinking (22% in the first year), and few return to heavy drinking (5% to frequent heavy use in 1 year, 20% at 5 years).

Alcohol is directly toxic to the gastric mucosa and can lead to asymptomatic or symptomatic gastritis. Vomiting can lead to a Mallory-Weiss tear and hematemesis. Alcohol can lead to stomatitis, esophagitis, pancreatitis, duodenitis, esophageal cancer, and gastric cancer. Endoscopy is warranted for persistent reflux symptoms or epigastric pain, particularly if weight loss is present or if patients are aged 40 years and older.

In people with alcohol use disorder, amylase often is elevated because of chronic parotitis, rather than due to pancreatitis. Epigastric pain might be indicative of pancreatitis, a potentially lethal complication of alcohol use, for which abdominal computed tomography (CT) is the most sensitive and specific test. CT is indicated if the presentation is atypical, fever is present, or the patient does not improve as expected. Severity can range from mild epigastric symptoms to a mortal condition complicated by acidosis, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and hypovolemia. Standard therapy for acute pancreatitis (volume repletion, nothing by mouth, and parental opiate pain control) should be instituted early.

Renal and Metabolic Consequences

Hepatic disease can lead to renal consequences, which manifest as nephrotic syndrome and glomerulonephritis from chronic hepatitis C and hepatorenal syndrome in severe cirrhosis. Acute renal failure can occur from rhabdomyolysis after alcohol intoxication or seizure or from volume depletion from vomiting, diarrhea, and diuresis.

People with heavy alcohol use who present for acute medical care should be evaluated for fluid and electrolyte abnormalities. Medical management should focus on volume repletion at least until the patient no longer manifests postural changes in blood pressure and heart rate and until excess losses are not continuing.

Both metabolic acidosis and alkalosis can occur as a result of heavy drinking. In cases of acidosis, it is important to determine an anion or osmolar gap; if present, ingestion of substances other than ethanol (ethylene glycol or methanol ingestions if an osmolar gap is present) needs to be ruled out. These ingestions require prompt treatment to prevent blindness or death. In the absence of an anion gap, diarrhea is the most common cause of acidosis. If an anion gap is present, the differential diagnosis is broad but, in people with heavy alcohol use, should focus on lactic acidosis (from sepsis, injury, severe pancreatitis, or after convulsion), ketoacidosis, and toxic ingestion. Alkalemia can occur as a result of respiratory alkalosis related to liver disease and hyperventilation or metabolic alkalosis from vomiting. Treatment for withdrawal (abstinence from alcohol, antiemetic control of vomiting, volume repletion; holding diuretics, if any) can help facilitate the resolution of the alkalemia. This is important as it can be associated with hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia, which are common deficiencies in people with heavy alcohol use. In addition, severe hypophosphatemia (unmasked when dextrose is given to malnourished people with heavy alcohol use), hypokalemia, and hypocalcemia are seen in these patients and will not correct until magnesium is replaced. Consider empiric replacement of magnesium as serum levels do not reflect total body magnesium stores. Oral replacement of magnesium and phosphate is usually possible, but intravenous replacement, with cardiac monitoring in the case of severe hypophosphatemia, may be necessary.

Hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia can be seen in people with alcohol use disorders as a result of pancreatic insufficiency or in end-stage cirrhosis.

Pulmonary Consequences

Alcohol intoxication can lead to respiratory depression and aspiration, which may result in a chemical or infectious pneumonia. Tachypnea can be the result of pulmonary infection, respiratory alkalosis of liver disease, alcohol withdrawal, or compensation for a metabolic acidosis.

Neurologic Consequences

Alcohol intoxication can lead to head trauma, and signs and symptoms of intracranial hemorrhage—particularly subdural hematoma—can be confused with intoxication. In addition, heavy drinking (in men one to two or more drinks a day and in women more than one drink per day) increases the risk for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Imaging of the brain is indicated when there are signs of significant head trauma and abnormal mental status, when focal neurologic deficits are present, or when neurologic symptoms do not resolve with declining alcohol levels. Alcohol can lower the seizure threshold in epileptics, and seizures may be the presenting sign of an intracranial hemorrhage.

Acute cognitive impairment caused by thiamine deficiency, or Wernicke-Korsakoff disease, presents with confusion, ataxia, or nystagmus. Parenteral thiamine, 100 mg administered before glucose, is the initial treatment. Chronically, Wernicke-Korsakoff disease can develop into Korsakoff syndrome, a memory impairment classically characterized by confabulation. More commonly, chronic alcohol use disorder is associated with nonspecific dementia. Alcoholic cerebellar dysfunction results in ataxia and incoordination and is often irreversible.

People with alcohol use disorder can suffer from peripheral neuropathy, usually from vitamin deficiency, pressure on a nerve, or ethanol toxicity. It presents as sensory disturbance, including burning, pain, and numbness in a stocking-glove distribution.

Alcohol withdrawal symptoms (diaphoresis, tremor) begin 6 to 48 hours after the last drink. Many patients can be managed as outpatients, provided symptoms are little and there are no comorbidities. Benzodiazepines are the only medications proven to ameliorate symptoms of withdrawal, to decrease the risk of seizures and delirium, and to speed achievement of a calm but awake state in patients experiencing delirium. Pharmacotherapy is indicated for asymptomatic patients at risk of complications (i.e., with comorbidities or past seizures) and for those with significant symptoms (use tools such as CIWA [Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale]). Seizures, when they occur, almost always resolve spontaneously. Seizures can recur and generally do so within 6 hours of the first seizure. Benzodiazepines prevent further seizures and progression to delirium tremens. Delirium should be managed in a setting where frequent and intensive monitoring is possible because of the risk of death from the condition and its treatment. Other medications to be used as adjunctive therapies include β-blockers for tachycardia, clonidine for hypertension, and haloperidol for psychosis or agitation, when these signs and symptoms fail to respond to benzodiazepines. The tachycardia can complicate underlying medical conditions such as coronary artery disease by precipitating angina or myocardial infarction.

Infectious Diseases

Among people with alcohol use disorder, immune defenses are impaired through various mechanisms: undernutrition, splenic dysfunction, leukopenia, impaired granulocyte function, as well as suppression of the gag reflex during intoxication and overdose. Fever in people with alcohol use disorders cannot be attributed to a minor viral syndrome or withdrawal. Other causes must be reasonably excluded. Pneumonia is more common in people with alcohol use disorders and is associated with increased mortality risk. Tuberculosis must be considered in this population particularly in the presence of symptoms consistent with the diagnosis. Meningitis in people with alcohol use disorders has a broader etiology than in the general population. Brain abscess can result from poor dentition, leading to transient bacteremia and local infection, for example, in a preexisting subdural hematoma. In patients with cirrhosis and ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis can occur with minimal or absent abdominal tenderness. Diagnosis is made by paracentesis. Spontaneous bacterial empyema can occur when pleural effusion is present. Sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, are more common in people who drink heavily than in the general population, in part because sexual risk-taking behavior and potential sexual abuse are more common. In HIV-infected persons, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and other opportunistic infections must be considered when pneumonia is diagnosed.

Trauma

Trauma, including physical and sexual abuse, can lead to poorer addiction treatment outcomes. Addiction specialists should be attuned to the high rates of injury (both past trauma and the risk of future injury) when counseling people with alcohol use disorders.

Alcohol can interfere with balance and coordination as well as judgment, thus predisposing to injury. Heavy episodic drinking poses a particular risk of injury and accidents. As these patients often present to emergency departments and trauma centers, these facilities should routinely screen for alcohol problems and refer patients with alcohol-related disorders for treatment.

Injury can be a motivating factor for discontinuing alcohol use or a focus of counseling to prevent future injuries.

Endocrinologic Consequences

Alcohol causes sexual dysfunction and hypogonadism in men, both through direct effects on the testes and through secondary effects in chronic liver disease, in which gynecomastia may be seen. In women, alcohol delays menopause and is associated with menstrual disorder and decreased fertility. Alcohol increases high-density lipoprotein but also serum triglycerides, which can lead to heart disease, hepatic steatosis, and pancreatitis. Moderate drinking can decrease the incidence of diabetes mellitus, but more than three drinks a day increase the risk.

Fetal, Neonatal, and Infant Consequences

Even low amounts of alcohol consumed during pregnancy can lead to developmental disabilities and neurobehavioral deficits in the offspring. The fetal alcohol syndrome involves craniofacial abnormalities, growth retardation, and neurologic abnormalities, which persist lifelong. Because no safe amount of alcohol during pregnancy has been identified and there is no treatment for the effects of alcohol on the fetus, abstinence is recommended during pregnancy.

Hematologic Consequences

In addition to the iron deficiency anemia that can result from gastrointestinal hemorrhage or chronic blood loss, people with alcohol use disorders can develop pancytopenia (leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia) from alcohol’s direct toxic effects on the bone marrow or splenic sequestration as manifested in the splenomegaly associated with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. There may be leukopenia or an impaired quantitative and qualitative white blood cell response to infection. Megaloblastic anemia may be as a result of folate deficiency. If there is iron deficiency lowering the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and hemolytic anemias related to liver disease with reticulocytosis or megaloblastic processes simultaneously increasing it, MCV may be noncontributory in differentiating the cause of anemia; the red cell distribution width should be elevated in this situation.

The treatment for bone marrow suppression is abstinence. For iron deficiency, it is identification of the cause and iron replacement. For folate deficiency, treatment consists in folate replacement (after testing for concomitant vitamin B12 deficiency and treating it as needed). Coagulopathy usually is a result of chronic liver disease, though a trial of vitamin K replacement is warranted at least once.

Oncologic Risks

Alcohol is a risk factor for several malignancies including of the lip, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, stomach, breast, liver, intrahepatic bile ducts, prostate, and colon. The risk is particularly increased with concurrent tobacco use. Even moderate levels of alcohol use may increase risk of certain cancers. For example, breast cancer risk increases with consumption of one to two standard drinks per day.

Musculoskeletal Consequences

Intoxication to the point of overdose may result in the individual’s remaining in one position for prolonged periods of time, which can lead to compression nerve palsies, rhabdomyolysis, and compartment syndrome. Surgical consultation is required for the latter.

Hyperuricemia and gout are more common in alcohol use disorders. Treatment is with colchicine, using caution in renal or hepatic insufficiency, or indomethacin, using caution in the presence of gastritis or renal insufficiency. A brief course of corticosteroids and a single injection of adrenocorticotropic hormone may be safer choices for persons with alcohol use disorders. Chronic treatment in the setting of renal disease, tophaceous gout, or polyarticular gout should be with allopurinol or probenecid.

Excessive regular alcohol use or heavy episodic drinking increases the risk of skeletal fracture, through higher risk of trauma or alcohol-related osteopenia or both. Heavy alcohol use can lead to osteonecrosis of the bone, such as that at the femoral head.

Vitamin Deficiencies

Malabsorption and poor dietary intake can lead to deficiencies of thiamine, pyridoxine, niacin, riboflavin, vitamin D, zinc, and fat-soluble vitamins when there is malabsorption because of pancreatic disease. Vitamin replacement is safe and should be done empirically.

Consequences in the Perioperative Patient

Heavy alcohol consumption is a risk factor for postoperative complications. In the perioperative period, withdrawal is a concern, and both withdrawal and postoperative pain must be managed appropriately. Attempting to achieve abstinence prior to elective surgery has been shown to reduce morbidity.

Sleep

Though alcohol can help people fall asleep, it also can be stimulating and lead to disrupted sleep and daytime fatigue. Alcohol increases the risk of obstructive sleep apnea and worsens the disease (because of its depressant effects on respiration and relaxation of the upper airway) and can increase the risk of periodic limb movements of sleep. Treatment should include attention to sleep hygiene and pharmacotherapy with drugs with a low or no risk of dependence (e.g., trazodone).

Tobacco

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable illness and premature death. Its adverse health effects range from cosmetic damage to severe illness as outlined in the following.

Smoking increases the risks of myocardial infarction and sudden death due to poorer control of hypertension and atherosclerosis. It can precipitate angina by facilitating vasospasm and hypercoagulability and can precipitate dysrhythmia. Smokers are at higher risk of cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular disease. These risks decrease promptly after smoking cessation.

Smoking is the leading cause of both chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchogenic carcinoma. It leads to pulmonary hypertension, interstitial lung disease, and pneumothorax. The decline in lung function and mortality risks of both diagnoses can be decreased with smoking cessation. In addition, smoking is associated with cancer of the oral cavity, larynx, esophagus, bladder, kidney, pancreas, stomach, and cervix. These risks decrease with cessation.

Smoking causes gastric and duodenal ulcers and can exacerbate gastroesophageal reflux disease. Smoking cessation, in addition to pharmacotherapy, is usually necessary for effective treatment. It has hypercoagulable effects and is a risk factor for deep vein thrombosis. Tobacco use is known to increase the risk of Graves disease (hyperthyroidism) and hypothyroidism, increase insulin resistance and the risk of diabetes, and decrease estrogen in both genders and is associated with decreased BMD, osteoporosis, and fractures. In men, it is one of the leading causes of erectile dysfunction and decreases sperm number and function. Tobacco use during pregnancy causes low birth weight, spontaneous abortion, and perinatal mortality and may increase risks of sudden infant death syndrome and neurodevelopmental impairment.

Consequences in the Perioperative Patient

Smoking increases the risk of postoperative pneumonia, atelectasis, reactive airways exacerbations, and respiratory failure. If possible, smoking cessation at least 2 months before elective surgery is advisable.

Cessation and Treatment of Withdrawal

Nicotine replacement, bupropion or varenicline, if appropriate, should be provided for medically ill patients who are hospitalized as nicotine withdrawal and craving can complicate treatment for other medical illnesses. Nicotine replacement can precipitate myocardial ischemia, but the alternative, smoking a cigarette, also can do so. Therefore, in general, even smokers with coronary artery disease can use nicotine replacement, unless they are experiencing unstable angina or myocardial infarction.

Opiates, Cocaine, and Other Drugs

Medical, surgical, and other complications of drugs are related to their route of administration (unsafe injection, inhalation) and to their organ effects, particularly their effects on the brain.

Injection Drug Use

Intravenous drug use is a major risk factor for HIV and hepatitis C infection. Tetanus can develop in nonimmune individuals. False-positive screening tests for syphilis often are found in injection drug users; therefore, treponemal specific tests are needed to determine the diagnosis.

Due to unsafe injections, skin and soft tissue infections are common in injection drug users. Commonly caused by staphylococci and streptococci, local epidemiology and practices can point to other, unusual causative pathogens (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia species) and polymicrobial infections from use of saliva to prepare the injection. Cellulitis and minor infections can usually be treated with penicillin, cephalosporins, or macrolides. Abscesses need additional surgical drainage. Soft tissue infections become life threatening if fasciitis significant local ischemia (as with cocaine injection) develops. Intravenous injection can result in septic thrombophlebitis, arterial injection with embolus and digital ischemia, and infection or venous valvular damage in the extremities, marked by leg ulcers, edema, and a propensity to develop deep vein thrombosis.

One of the most serious infectious consequences of injection drug use is bacterial endocarditis. Thus, in an injection drug user, fever even in the absence of cardiac murmurs and other typical signs of subacute bacterial endocarditis needs to be worked up (blood culture, eventual empiric antibiotic treatment). Mycotic aneurysms, endophthalmitis, congestive heart failure, brain, spleen, or myocardial abscesses and emboli, renal failure from interstitial nephritis, pulmonary septic emboli with effusions, stroke, and heart block can complicate the course. Injection drug users can also develop septic arthritis in unusual locations (sternoclavicular or sacroiliac joints), spinal epidural or vertebral infections, osteomyelitis, or meningitis.

In addition to infectious complications, injection of drugs can lead to pulmonary and hepatic talc granulomatosis from injected crushed tablets containing talc, pulmonary hypertension from granulomatous disease or drug-related vasoconstriction, needle embolization, pneumothorax or hemothorax from injection into large central veins gone awry, and pulmonary emphysema related or unrelated to talc granulomatosis.

A common renal complication related specifically to injection drug use is nephropathy, primarily because of HIV infection. Amyloidosis and nephrotic syndrome can occur because of chronic skin infections. Hepatitis C infection can lead to glomerulonephritis. The coagulopathy that results from liver and kidney disease in injection drug users can lead to neurologic complications, particularly hemorrhagic stroke. Cerebral infarction can result from injection of crushed tablets and even from a melted suppository (intravenously and via inadvertent intra-arterial injection).

Inhalation of Drugs

Inhalation of drugs has effects related to the size of the particles: Larger particles affect the airways and smaller ones the alveoli. In addition to the granulomatous complications listed above, chronic bronchitis from inhaled smoke, bronchospasm, barotrauma with resultant pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum from prolonged breath holding or stimulant use, hemoptysis from airway irritation, and emphysema from inhaled tobacco, marijuana, or opiates can occur. Freebasing (inhalation of burned precipitate of cocaine) can lead to upper airway and facial burns.

Withdrawal

Though the withdrawal is not fatal in an otherwise healthy person, in the acutely ill or hospitalized patient, it should be treated for symptomatic relief and to prevent hyperadrenergic states that complicate treatment of the acute medical problems (e.g., coronary syndromes).

Neurologic Consequences

Seizures can occur as a result of sedative withdrawal, stimulant use, or proconvulsant metabolites (meperidine). Similarly, hemorrhagic stroke can occur with the use of methamphetamines, phenylpropanolamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and phencyclidine from hypertension, vasculitis, or other vascular mechanisms. Cocaine use can lead to both hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes. Anabolic steroids can cause stroke by promoting hypercoagulability. Though classic syndromes of dementia have not been described for users of drugs other than alcohol, chronic cognitive deficits can be seen in users of cocaine, sedatives (barbiturate), and toluene. Neuropathy (including plexopathies and Guillain-Barré syndrome) may be caused by heroin use, compression neuropathy in any drug user, quadriplegia in glue sniffers, and combined systems degeneration from vitamin B12 deficiency induced by nitrous oxide use. Parkinsonism can develop from the use of a meperidine analogue, MPTP.

Gastrointestinal Consequences

In addition to hepatitis C, which is almost universal in injection drug users, cocaine itself can cause hepatic necrosis, probably because of ischemia. Ecstasy and phencyclidine use has been reported to cause liver failure. Androgenic steroids can cause hepatic toxicity. Anticholinergic and opiate abuse will cause constipation. “Body packing” (transporting cocaine, heroin, or other drugs in bags that are swallowed) can lead to mechanical obstruction of the intestines. Rupture can lead to overdose.

Hematologic Consequences

Amyl nitrate, isobutyl nitrate, and other “poppers” can cause methemoglobinemia.

Cardiovascular Consequences

In addition to endocarditis and myocardial abscess, drugs of abuse can directly affect the heart and blood vessels. Cocaine can cause severe hypertension, cardiomyopathy, cardiac dysrhythmias, angina, myocardial infarction, sudden death, and stroke. Chest pain often occurs during or after cocaine use, but most persons evaluated in emergency departments with chest pain and cocaine use do not have myocardial infarction. Nonetheless, heart attacks do occur and are thought to be related to coronary vasospasm, in situ thrombosis, or the accelerated development of atherosclerosis. Other stimulants can also produce cardiac complications. Anabolic steroids can lead to coronary artery disease as well as cardiomyopathy. Drugs with anticholinergic effects (muscle relaxants, antihistamines, and antidepressants) cause tachycardia and dysrhythmias in intoxication or overdose. Inhalants (volatile fluorocarbons) can cause dysrhythmias.

Renal and Metabolic Consequences

Any drug that leads to sedation with intoxication or overdose can lead to muscle compression and rhabdomyolysis and thus to acute renal failure. Rhabdomyolysis can also be seen with amphetamine, cocaine, and phencyclidine use. Cocaine can lead to accelerated hypertension and renal failure, hypertensive nephrosclerosis, thrombotic microangiopathy, and renal infarction. Amphetamines can result in a drug-related polyarteritis nodosa. Ecstasy use can lead to hyponatremia when users drink excess water to prevent the hypovolemia associated with its use. Toluene inhalation can lead to metabolic acidosis.

Injury

Though much of the literature focuses on alcohol as a risk factor for injury, cocaine and other drugs also have been associated with an increased risk of motor vehicle crash and other violent injuries, including fatal shootings.

Oncologic Risks

Though the magnitude of risk remains unclear, marijuana, when smoked, can lead to squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and to lung cancer.

Pulmonary Consequences

Drugs that produce sedation with use or overdose can lead to respiratory depression and death. Atelectasis can develop, as can aspiration and chemical pneumonitis. Opiate use can lead to bronchospasm, as a result of its stimulation of histamine release, and pulmonary edema in the setting of overdose. The pulmonary consequences of sedatives are limited primarily to respiratory depression and arrest from overdose, worsening of sleep-disordered breathing, as well as tachypnea, hyperventilation, and respiratory alkalosis from withdrawal syndromes.

Marijuana use can lead to obstructive lung disease and fungal infection from contamination. Cocaine use can lead to nasal septal perforation, sinusitis, epiglottitis, upper airway obstruction, and hemoptysis, primarily from irritant and vasoconstrictive effects. Cocaine use can lead to pulmonary hemorrhage, edema, hypertension, emphysema, interstitial fibrosis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The treatment for most of these diseases is withdrawal of the cocaine and supportive care, though corticosteroids and bronchodilators are warranted in some cases. Pulmonary hypertension and edema can result from use of stimulants (specifically amphetamines).

Inhalants can lead to methemoglobinemia, tracheobronchitis, asphyxiation, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Nitrous oxide can cause respiratory depression and hypoxemia. Anabolic steroids can induce prothrombotic states and lead to pulmonary embolism.

Endocrinologic Consequences

Most drugs of abuse can affect a variety of hormone levels. Opiates can impair gonadotropin release, which may lead to impaired sperm motility in men, and women may have menstrual and ovulatory irregularities. Cocaine is a risk factor for the more frequent occurrence of diabetic ketoacidosis, in part because of adrenergic effects. Barbiturate use can lead to osteomalacia from vitamin D deficiency. Clinical metabolic consequences have been clearly linked to use of anabolic steroids. Women develop androgenization, and lipids are adversely affected.

Consequences in the Perioperative Patient

As with other substances, attention to and treatment of withdrawal symptoms can avert development of tachycardia and hypertension, which may complicate interpretation of assessments and operative and anesthetic treatments. The anesthesiologist must be informed of any recent drug use because of potential interactions between β-blockers and cocaine and because of the potentiation of sedative and anesthetic drugs. Finally, anesthesia and pain management generally require much higher doses than usual in the opiate-dependent patient. Nutritional issues often require attention in addicted persons undergoing surgery, as wound healing may be impaired.

Sleep

Many persons with addictive disorders experience sleep disturbances, because of the effect of the drug used, lifestyles, or comorbid psychiatric conditions. The often desired effect of drugs on sleep (stimulants suppresses, opioids and nicotine reduce sleep) can contribute to their use for self-medication. The management of sleep disorders, particularly insomnia, therefore, is difficult but important in addicted persons. Attention to sleep hygiene (i.e., a quiet location, using the bed only for sleep and sex, and elimination of napping) and judicious use of drugs less likely to lead to misuse, such as trazodone, are the best approaches.

Fetal, Neonatal, and Infant Consequences

No clear teratogenic effects of opiates are known, but opiate exposure in utero can lead to the neonatal abstinence syndrome, which manifests primarily with seizures. Benzodiazepines have been associated with cleft lip and palate, although studies may have been confounded by alcohol use. Toluene and other inhalants use can cause an embryopathy, preterm labor, and intrauterine growth retardation. Caffeine in pregnancy is probably relatively safe, although some reports of increased fetal loss suggest minimizing its use during pregnancy. Dextroamphetamine and cocaine are associated with teratogenesis. Cocaine during pregnancy can induce neonatal irritability and also may cause behavioral and learning disorders.

COMMON MEDICAL PROBLEMS IN PERSONS WITH ADDICTIVE DISORDERS

Persons with addictive disorders in principle suffer from the same medical conditions as nonaddicted persons, but aspects specific to addiction need to be addressed when managing common medical problems.

Coronary artery disease is particularly common in persons with alcohol and other drug abuse because of concomitant tobacco use disorder. Angina can be complicated by alcohol, opiate, and sedative withdrawal, as well as cocaine and other stimulant use when the hyperadrenergic states precipitate anginal attacks. β-Blockers are drugs of choice, as these also decrease sympathetic activation associated with drug withdrawal. Of note, simultaneous use of β-blockers and cocaine should be avoided because of the unopposed vasoconstriction that can result. Aspirin and other treatments for acute coronary events (heparin, tissue plasminogen activator, and similar anticoagulants) can be problematic in persons at risk for internal bleeding, such as people with alcohol use disorder with gastritis or liver disease, or unrecognized intracranial bleeding.

The diagnosis of essential hypertension can be problematic in persons with addictive disorders as elevation can be a secondary to pain, withdrawal, or intoxication, depending on the substance used. Ideally, hypertension should be diagnosed by at least three elevated blood pressure measurements during prolonged abstinence. Treatment of hypertension is the same as in persons without addictive disorders, but diuretics can be somewhat riskier in people with alcohol use disorder because of the adverse effects on potassium balance. β-Blockers are excellent alternatives unless there is a positive history of cocaine use.

Diabetes is more difficult to manage in persons with addictive disorders, due to medication adherence issues and often less regular eating habits, in addition to the effects of alcohol on glucose metabolism. Heavy alcohol users are more prone to prolonged and more severe hypoglycemia from the sulfonylurea agents often used to treat type 2 diabetes. Options for the management of diabetes in alcohol use disorder are limited. Thiazolidinediones are relatively contraindicated because of the possibility that these may cause hepatic damage. Metformin should not be given to patients with hepatic impairment or those at risk for lactic acidosis. Insulin injections are preferred, though use of sulfonylureas with careful monitoring is reasonable.

In addition to having etiologic roles in cancers, addiction can lead to difficulties in cancer management. First, any renal, hepatic, or cardiac consequences of addiction can limit the choice of chemotherapeutic agents. Pulmonary consequences of tobacco use may limit surgical options. Finally, pain management can be complicated by ongoing or past addiction.

CONSEQUENCES IN OLDER ADULTS

In older adults, lower amounts of alcohol are associated with more adverse consequences than in younger ones because of their lower body mass and body water, alcohol dehydrogenase concentration, and impaired ability to develop tolerance. Hip fracture, a leading cause of death in older adults, can result from an increased propensity to fall related to alcohol use and to osteopenia. Older adults are more susceptible to injury from motor vehicle crashes and even more so when alcohol is used. Certain medications are less effective or can be harmful when taken with alcohol. Older adults are more susceptible than are younger individuals to alcohol’s chronic brain-damaging effects, including cognitive deficits, and are less likely to recover completely from those effects.

In addition to greater susceptibility, alcohol can cause many consequences in older adults that may be misdiagnosed as other common medical problems. For example, the tremor of withdrawal may be diagnosed as Parkinson disease or an essential tremor. Conditions common in the elderly (dementia, malnutrition, self-neglect, functional decline, sleep problems, anxiety or depression, cardiovascular disease, cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, incontinence, fatigue, neuropathy, sexual dysfunction, pneumonia, fractures, seizures, and cerebellar degeneration) need to consider the potential causal contribution of alcohol.

Alcohol and other drug abuse can contribute to the worsening of chronic illness (such as hypertension), interference with medication adherence, and side effects. The effects of smoking are of great significance in older adults because smoking-related diseases often appear with aging and can be exacerbated by continued smoking.

KEY POINTS

1. Care for patients with addictions needs to address both their medical and surgical needs and those related to substance use.

2. When caring for patients with addiction, keep in mind that unhealthy substance use can affect virtually any organ system in the body.

3. Preventive care should be targeted to the patients’ background and follow current guidelines.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. Choose the best answer: In patients with opiate use disorder:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree