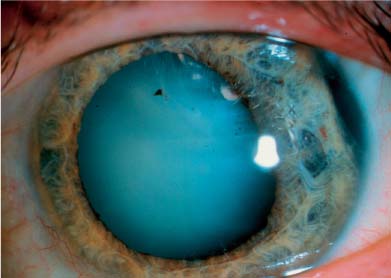

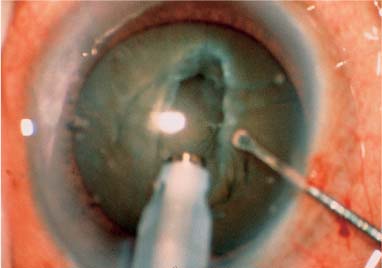

Chapter 16 The mature cataract may represent one or both of two clinical entities, namely a cortical mature or a nuclear mature cataract. The cortical variety (Fig. 16–1) has an opaque, milky white, (potentially) liquefied cortex that, at surgery, obscures the red reflex and the nature of the underlying lens nucleus. The nuclear mature cataract (Fig. 16–2) contains an ultrafirm and visibly dark reddish brown or (near) black nucleus in which an epinucleus cannot be delineated and little to no cortex remains; it may consist only of “rock-hard” nuclear lens material and lens capsule. Given that a very dark cataract can obscure the red reflex and that a white cataract may harbor an ultradense nucleus, there may be crossover between the two clinical entities. Mature cataracts pose certain challenges to the anterior segment surgeon and add outcome risks to patients. Because phacoemulsification may be anything but routine in these cases, ophthalmologists have historically considered alternative surgical methods when faced with mature cataracts of either type. Nevertheless, observant presurgical evaluation, careful surgical planning, and skillful and diligent surgical technique can combine (with good fortune) to afford the patient the opportunity for rapid visual and physical recovery by means of small-incision cataract surgery. Patients contemplating surgery for a mature cataract should be counseled regarding the likelihood of increased surgical time, a slower recovery of vision postoperatively, and an increased risk of intraoperative complications. Likewise, the surgeon must be properly prepared for the increased demands of successful small incision surgery in these cases. The etiology of the cortically mature cataract is generally unknown, but the condition is characterized by hydration of the lens cortex sufficient for the cortical lens fibers to become swollen and milky white. In the extreme case the cortex becomes fully liquefied, leaving only a small, firm, floating nucleus within a sac of white fluid; this rare special condition is referred to as a morgagnian cataract. It is unclear why certain cataracts become cortically mature unless a specific rent in the capsule can be identified. However, the likely final common pathway is the mixture of aqueous humor with lens material. Eyes without demonstrable trauma or physical openings in the lens capsule have most likely imbibed aqueous through the ordinarily semipermeable lens capsule. In these cases the lens generally swells, inducing an increased hydrostatic or intralenticular pressure. Lens swelling may be sufficient to cause narrowing of the chamber angle and the potential for acute phacomorphic glaucoma. Raised pressure within the capsular bag (or the eye) is but one factor that can complicate surgery in this group of patients. Capsulorrhexis can be very difficult, given that the capsule may be very friable and may readily tear to the equator because the capsule is “stretched” by the increased water content of the lens. Furthermore, the surgeon is hindered by the absence of the red reflex, making capsulorrhexis yet more challenging. Finally, these cases may be problematic because the density of the nucleus is obscured and cannot be evaluated until after the anterior capsule has been opened. Should the nucleus be very hard, phacoemulsification presents added risks because no epinucleus is present and the milky cortex may tend to wash out, leaving little to no protective cushion for the posterior capsule during the emulsification process. FIGURE 16–1 Mature cortical or intumescent cataract. The cataract obscures the red reflex. The surgical approach to the cortically mature cataract begins with the preoperative evaluation. Gross presurgical vision testing can be assessed with two-point white light discrimination, perception of color with bright light, and entoptic phenomena. Additionally, the condition of the corneal endothelium should be evaluated with specular microscopy or slit-lamp examination because it may be necessary to elevate the nucleus into the anterior chamber during surgery, should the capsulorrhexis fail or the posterior capsule rupture. If the nucleus is very firm and the endothelium poor, emulsification in the anterior chamber may be contraindicated. Lastly, the preoperative evaluation should rule out phacolysis with lens-induced inflammation and secondary elevation of intraocular pressure. In this case intense topical steroids and/or ocular hypotensive agents may be necessary prior to surgery. Phacomorphic angle closure from an intumescent white lens may require laser iridotomy prior to surgery. FIGURE 16–2 Mature nuclear cataract. Brown or black nucleus with little or no epinucleus. Anterior capsulorrhexis remains the most important and the most challenging aspect of the surgery. Generally, if one can complete the capsulorrhexis, all else is likely to succeed. The factors that make the capsulorrhexis difficult, as discussed above, include poor visibility and the friable nature of the capsule, particularly if it is under tension from increased hydrostatic pressure within the capsular bag. The surgical game plan must consider these issues. Table 16–1 lists the presently available options for increasing visibility during the capsulorrhexis. The surgeon can alter the parameters of the microscope, increasing magnification and slowing the motorized changes in magnification, zoom, and X-Y position. In that manner the cut edge of the capsule may be kept in the surgeon’s view. Additionally, reducing the ambient room lighting will eliminate glare and improve the visibility of the events occurring in the anterior chamber. Another commonly encountered problem of visibility may occur when the capsule is first punctured, as liquefied cortex may escape from the capsular bag and mix with the aqueous or the viscoagent. This may be prevented by “overfilling” the anterior chamber with a highly retentive viscoagent prior to initiating the capsule tear. This also helps to avoid peripheralization of the capsulotomy by creating a tamponade against the rapid escape of milky cortex arising from high intralenticular pressure. Additionally, when working with an intumescent white cataract, the surgeon may consider making a small circular capsulotomy initially and enlarging it later when the risks of peripheralization are reduced. Should cortex enter the chamber during capsulorrhexis, and preclude an adequate view, it may be necessary to move it out of the way with additional viscoelastic or evacuate it with the irrigation and aspiration (I&A) handpiece or cannula.

MANAGEMENT OF THE

MATURE CATARACT

CORTICAL (INTUMESCENT) MATURE CATARACTS

Alter microscope parameters Increase magnification Reduce focus speed Reduce zoom speed Reduce X-Y speed |

Turn off room lights |

Liberal use of viscoagent |

Side lighting—retinal endoilluminator |

Stain the anterior capsule Indocyanine green (ICG) Trypan blue Fluorescein sodium Methylene blue Gentian violet Brilliant green Autologous blood |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree