Jeffery N. Wilkins, MD, FASAM, DFAPA, Itai Danovitch, MD, MBA, and David A. Gorelick, MD, PhD, DLFAPA

46

STIMULANTS

The acute effects of stimulants are attributable principally to increases in catecholamine neurotransmitter activity, mediated through blockade of presynaptic neurotransmitter reuptake pumps (as by cocaine) and by presynaptic release of catecholamines (as by amphetamines). Resulting stimulation of brain reward circuits (corticomesolimbic dopamine circuit) mediates the desired (and addicting) psychological effects of stimulants. Blockade of presynaptic catecholamine reuptake sites or postsynaptic receptors should, in principle, be an effective treatment for stimulant intoxication. Bupropion, aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and modafinil block acute subjective effects in human laboratory experiments. Another method is to decrease drug availability in the central nervous system (CNS) by binding it peripherally with antidrug antibodies or by increasing its catabolism, but this has not yet been evaluated in humans.

Initial desired effects of stimulants include increased energy, alertness, and sociability; elation; euphoria; and decreased fatigue, need for sleep, and appetite. With high dose or repeated use, unwanted effects such as anxiety, irritability, suspiciousness, impaired judgment, stereotyped behavior, and psychotic symptoms such as paranoia and hallucinations (up to three fourths of users) can appear. Stimulant users typically remain alert and oriented, but the delusional state may impair judgment, cognition, and attention.

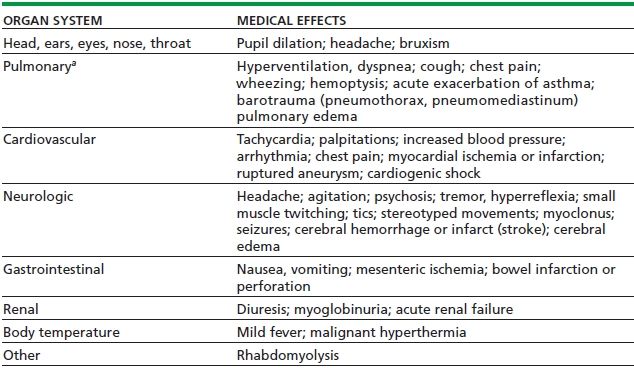

Patients with stimulant-induced psychoses may closely resemble those with acute schizophrenia and may be misdiagnosed as such. Cocaine-induced psychosis may differ from acute schizophrenic psychosis in having less thought disorder and bizarre delusions and fewer negative symptoms. Tactile hallucinations are especially typical of stimulant psychosis. Panic reactions are common. Very severe stimulant intoxication may produce an excited delirium or organic brain syndrome that can be fatal. Patients should be evaluated promptly for an acute neurologic lesion or preexisting neuropsychiatric condition (Table 46-1).

TABLE 46-1. ACUTE MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS OF STIMULANT INTOXICATION

aAll pulmonary complications except hyperventilation and pulmonary edema come primarily from the smoked route of administration.

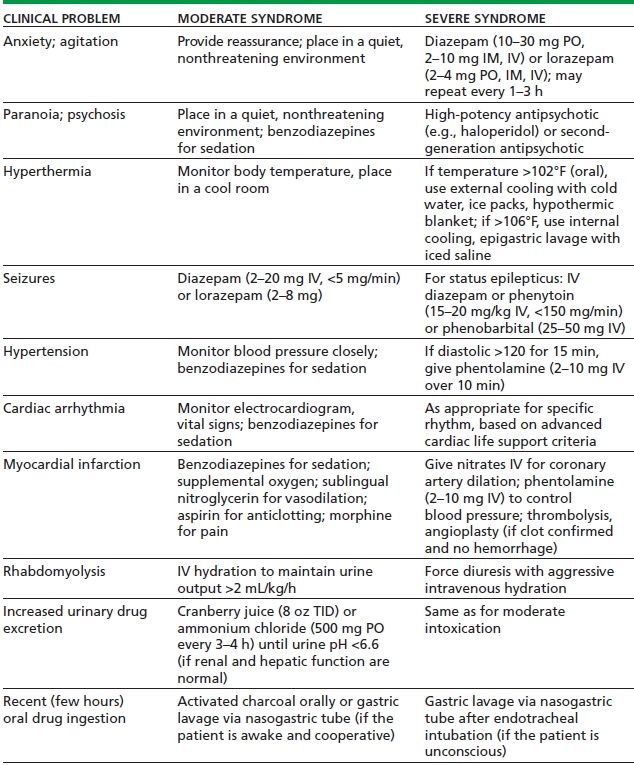

Initial treatment approach is nonpharmacologic: observation in a quiet environment with minimal sensory stimulation. Treatment staff should interact in a calm and confident manner, using the “ART” approach: Acceptance of the patient’s immediate needs; Reassurance that the condition is due to the drug and likely will dissipate within a few hours; and Talk down, to provide reality orientation. Physical restraints should be avoided, as they can increase risk of hyperthermia and rhabdomyolysis. If medication is needed to control agitation or psychosis, benzodiazepines are preferred over antipsychotics. If an antipsychotic is needed to control psychosis, high-potency agents are preferred because of their minimal anticholinergic activity. Psychiatric symptoms that persist beyond a few days warrant hospitalization and further evaluation.

About 1% to 6% of patients with cocaine-associated chest pain and up to one fourth of those with methamphetamine-associated chest pain will have an acute myocardial infarction with risk of infarction greatest during the first 1 to 3 hours after cocaine use. The first priority is maintenance of basic life support functions. Severe hypertension that lasts >15 minutes should be treated promptly to avoid CNS hemorrhage.

Benzodiazepines in sedative doses are the initial treatment of choice for both acute cardiovascular and CNS toxicity from stimulants. β-Adrenergic blockers such as propranolol or esmolol are contraindicated because of the risk of unopposed α-adrenergic stimulation by the stimulant, resulting in vasoconstriction and worsening hypertension. Treatment of cocaine-induced cardiac tachydysrhythmias begins with correction of any exacerbating conditions. Arrhythmias occurring immediately after cocaine use are usually due to the sodium channel–blocking action of cocaine. Lidocaine and class IA antidysrhythmic medications should be avoided. Treatment of cocaine-associated cardiac arrest is the same as for non–cocaine users; the outcome may be more favorable than for drug-free patients. Treatment of stimulant-associated acute coronary syndrome resembles that for the non–drug-associated syndrome, except for avoidance of β-adrenergic blockers and labetalol (Table 46-2).

TABLE 46-2. TREATMENT OF ACUTE STIMULANT INTOXICATION

Abrupt cessation of stimulant use is associated with depression, anxiety, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, anergia, anhedonia, increased drug craving, increased appetite, hypersomnolence, and increased dreaming (because of increased rapid eye movement sleep). Symptoms are mild and self-limited, resolving within 1 to 2 weeks. Hospitalization is rarely indicated and does not improve short-term outcome for stimulant addiction.

No medication is consistently effective in controlled clinical trials, nor is any medication approved for this indication by any national regulatory authority. Symptoms are best treated supportively with rest, exercise, and a healthy diet. Short-acting benzodiazepines such as lorazepam are helpful for agitation or sleep disturbance. Severe or persistent (>2 to 3 weeks) depression may require antidepressant treatment.

HALLUCINOGENS

Hallucinogens fall into two different chemical groups: serotonin or tryptamine related (including LSD, psilocybin, or N,N-dimethyltryptamine) and phenylethylamine or amphetamine related (including 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylethylamine [mescaline], 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine [DOM, STP], or 3,4,5-trimethoxyamphetamine). 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “Ecstasy”) has characteristics of both a hallucinogen and a stimulant and is considered below.

Hallucinogens have in common the ability to dramatically change sensory perceptions. Mood can vary from euphoria and feelings of spiritual insight to depression, anxiety, and terror. Hallucinations are common although reality testing usually remains intact. Panic reactions are more common in those who have limited experience with hallucinogens. Hallucinogens may trigger transient psychotic symptoms; however, development of a psychotic disorder is rare. Hallucinogen users, unlike patients with schizophrenia, usually retain at least partial insight and typically have visual rather than auditory perceptual disturbances. Hallucinogen ingestion may result in an acute toxic delirium.

Sympathomimetic effects are common, particularly pupillary dilation, hyperreflexia, piloerection, tachycardia, and increased blood pressure. Dry skin, increased muscle tone, agitation, and seizures are warning signs of a potential hyperthermic crisis. Complications that require treatment are rare in the absence of overdose.

After ensuring medical stability, the patient should be placed in a quiet environment with minimal sensory stimulation but should be observed. Physical restraints are contraindicated because they may exacerbate anxiety and increase the risk of rhabdomyolysis. The “talk-down” or reassurance technique may be helpful. For patients who do not respond to reassurance alone, benzodiazepines such as lorazepam or diazepam are the drugs of choice. If benzodiazepines are insufficient, a high-potency antipsychotic such as haloperidol may be needed. Phenothiazines should be avoided because they have been associated with poor outcomes and may exacerbate unsuspected anticholinergic poisoning.

Patients usually recover after several hours. Psychosis not resolving within 1 to 2 days suggests ingestion of a longer-acting drug such as phencyclidine (PCP) or DOM. Symptoms persisting beyond a few days raise the possibility of a preexisting or concurrent psychiatric or neurologic condition.

Withdrawal symptoms, including fatigue, irritability, and anhedonia, are reported by about 10% of hallucinogen users; however, there is no evidence to suggest a clinically significant hallucinogen withdrawal syndrome. There is no role for medication in the treatment of hallucinogen withdrawal.

MARIJUANA

The initial psychological effects of marijuana intoxication include relaxation, euphoria, slowed time perception, altered sensory perception, and increased appetite. Undesired effects include impaired concentration, anterograde amnesia, and motor incoordination. Marijuana-associated psychosis exhibits derealization/depersonalization and visual, rather than auditory, hallucinations.

Medical effects of marijuana intoxication include conjunctival injection, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, dry mouth, poor motor coordination, head jerks, and impairment of smooth pursuit eye movements. There are no well-established cases of human fatality from exclusively marijuana overdose. Marijuana smoking has been associated with atrial fibrillation and other tachydysrhythmias. Adverse effects of intoxication tend to be self-limited and usually can be managed without medication. Psychosis usually responds to low doses of second-generation antipsychotics.

Withdrawal symptoms are reported by up to half of heavy marijuana users, and withdrawal is now a recognized clinical syndrome in the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Symptoms are primarily psychological, including irritability, anxiety, depression, restlessness, anorexia, insomnia, and vivid or disturbing dreams. Physical symptoms are much less common—gastrointestinal distress, diaphoresis, chills, nausea, shakiness, and muscle twitches. The syndrome is usually mild and comparable to tobacco withdrawal. Withdrawal symptoms can serve as negative reinforcement for relapse among users trying to maintain abstinence. Management of withdrawal rarely requires treatment for intrinsic medical or psychiatric reasons (Table 46-3).

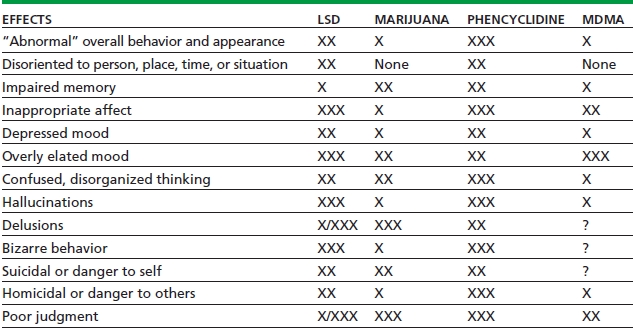

TABLE 46-3. ACUTE PSYCHOLOGIC AND BEHAVIORAL EFFECTS OF INTOXICATION WITH LSD, MARIJUANA, PCP, OR MDMA

Relative weighting: X, mild; XX, moderate; XXX, marked; /, common/rare; ?, insufficient research.

MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine.

DISSOCIATIVE ANESTHETICS

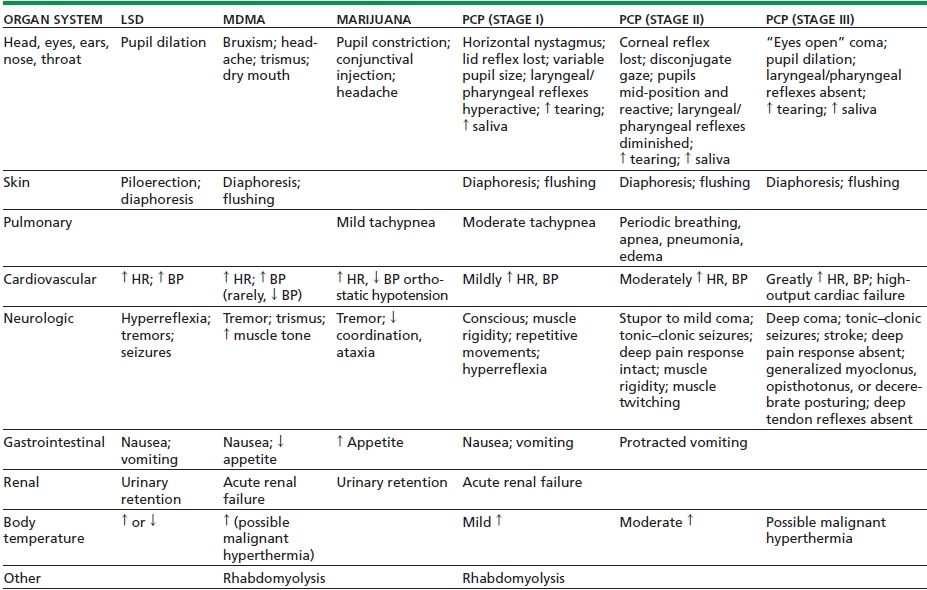

PCP and ketamine are noncompetitive antagonists of the NMDA-glutamate excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter receptor. Direct effects on other neurotransmitter systems may occur at high doses. Dextromethorphan (DXM) also antagonizes the NMDA-glutamate receptor and is widely available as an ingredient in over 100 different over-the-counter cough and cold medicines. At the recommended antitussive dose of 15 to 30 mg every 6 to 8 hours, adverse reactions are rare. About 5% to 10% of those with white European ancestry are unable to demethylate DXM to dextrorphan. Such individuals are at increased risk of toxicity from excess concentrations of DXM (Table 46-4).

TABLE 46-4. ACUTE MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS OF INTOXICATION WITH LSD, MDMA, MARIJUANA, OR PCP

MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine; HR, heart rate; BP, blood pressure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree