Summary by Joseph Samuel Insler, MD

44

Based on “Principles of Addiction Medicine” Chapter by William E. Dickinson, DO, FASAM, FAAFP, ABAM, and Steven J. Eickelberg, MD, FASAM

SEDATIVE–HYPNOTIC INTOXICATION AND OVERDOSE

Sedative–hypnotic toxicity appears very similar to the presentation of alcohol intoxication. Slurred speech and ataxia are seen with moderate toxicity, and stupor and coma may develop with more severe exposure. A major cause for concern is the development of tolerance to the therapeutic effects but not to the lethal effects. This is particularly true for the older sedative–hypnotics, and results in a decreased therapeutic index. Benzodiazepines, on the other hand, appear to be much safer and rarely cause death by themselves, though there is a risk when combined with other CNS depressants.

Assessment and maintenance of the airway is critical in managing sedative–hypnotic overdose. Certain clinical situations may call for intubation and/or evacuation of the stomach’s contents.

Flumazenil is a competitive benzodiazepine receptor antagonist with the ability to reverse the effects of benzodiazepines. It is sometimes given after medical procedures to reverse the effects of short-acting benzodiazepines, and it may be given to treat overdoses when it is known that benzodiazepines were ingested alone. The use of flumazenil outside of these parameters raises the risk of a rapid benzodiazepine withdrawal and may precipitate arrhythmias and seizures.

SEDATIVE–HYPNOTIC WITHDRAWAL

The use of sedative–hypnotics can lead to psychological and physiologic dependence. Withdrawal symptoms will occur during what is called an abstinence syndrome and may occur at any dose, though certain variables may affect the severity and clinical relevance.

A clinically significant withdrawal syndrome is likely to occur after discontinuation of a high-dose sedative–hypnotic previously taken for 2 to 3 months or a low-dose sedative–hypnotic previously taken for 4 to 6 months. It should be noted, however, that withdrawal symptoms can occur sooner and are influenced by three main factors: dose, duration of use, and duration of drug action.

Signs and Symptoms of Discontinuation

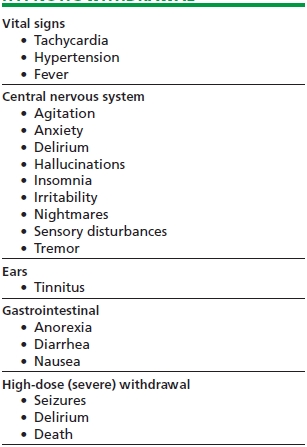

Table 44-1 lists the most common signs and symptoms of sedative–hypnotic withdrawal. The signs and symptoms of benzodiazepine discontinuation fall into four categories: (1) symptom recurrence or relapse, (2) rebound, (3), pseudowithdrawal, and (4) true withdrawal.

TABLE 44-1. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF SEDATIVE–HYPNOTIC WITHDRAWAL

Symptom recurrence or relapse pertains to the reemergence of the symptom for which the benzodiazepine was originally taken. This may include insomnia and anxiety, and it should be noted that these can reoccur without the presence of benzodiazepine dependence.

Rebound refers to the increase in severity of previously targeted symptoms shortly after benzodiazepine discontinuation.

Pseudowithdrawal can be compared to a placebo effect and occurs when the expectation of withdrawal leads to abstinence symptoms. True withdrawal occurs in individuals with benzodiazepine dependence who discontinue their use, and is notable for both physiologic and psychological symptoms.

True withdrawal stems from the morphologic changes induced by chronic benzodiazepine use and may be treated either by restarting the previous benzodiazepine or by giving a different one with cross-tolerance.

Any combination of the symptoms listed in Table 44-1 may occur during benzodiazepine withdrawal with varying severity throughout the initial 1 to 4 weeks of abstinence. Clinicians should remember that it is possible to have withdrawal consisting of solely subjective symptoms. Therefore, lack of objective clinical findings should not exclude a diagnosis of withdrawal.

Some individuals with long-term benzodiazepine use may experience a state referred to as prolonged withdrawal. This syndrome is notable for its unpredictable course and differing symptoms when compared to the acute withdrawal period and the time prior to initial benzodiazepine exposure.

Benzodiazepines induce neuronal inhibition through their action at the gamma-aminobutyric acid–benzodiazepine receptor (GABA-BDZ-R) complex. By activating GABA, benzodiazepines induce a chain of events that leads to the opening of membrane-bound chloride ion channels and the resulting hyperpolarization of the neuron.

Researchers have noted that continuous exposure to benzodiazepines leads to changes at the cellular level. These changes have been implicated in the development of tolerance and withdrawal symptoms.

As noted previously, the GABA system of the brain is thought to have an inhibitory role, while the glutamate system is thought to be primarily excitatory. These two systems are critical to maintaining balance within the brain. Chronic benzodiazepine use leads to neuroplastic changes in both systems in the body’s effort to maintain this balance. By increasing neuronal inhibition, benzodiazepines will lead to compensatory GABA down-regulation and glutamate up-regulation. When the benzodiazepine is stopped, the system is thrown off, and the excitatory activity of the glutamate system overwhelms the now diminished GABA system leading to the symptoms listed in Table 44-1.

Pharmacologic Characteristics Affecting Withdrawal

The elimination half-life is a critical variable when it comes to determining the onset of symptoms following discontinuation of use. Short-acting benzodiazepine withdrawal typically begins within 24 hours and peaks within 1 to 5 days. Long-acting benzodiazepine withdrawal occurs within 5 days and peaks at 1 to 9 days.

Higher doses and longer use increase both the likelihood and the severity of withdrawal symptoms. While it is possible for a withdrawal syndrome to occur with the cessation of low-dose benzodiazepines after <3 months, the symptoms are mild. More serious withdrawal syndromes are seen with high-dose benzodiazepine use beyond 6 weeks or with any dose for a significant period of time (such as a year).

Short-acting, high-potency benzodiazepines such as alprazolam and triazolam induce rapid tolerance and a more serious withdrawal syndrome.

Host Factors Affecting Withdrawal

In addition to the pharmacokinetics, there are other factors that contribute to the nature of benzodiazepine dependence and withdrawal. Individuals with psychiatric disorders commonly take benzodiazepines, and this group has been shown to have increased intensity of withdrawal symptoms. The literature reports a direct correlation between the degree of psychopathology and the intensity of the withdrawal symptoms.

The use of other substances can cloud the clinical picture during the benzodiazepine abstinence syndrome, and so it is important clinicians are aware of this and take the necessary precautions. Opioid withdrawal can exacerbate the adrenergic components of benzodiazepine withdrawal, while stimulant withdrawal may have the opposite effect. Comorbid alcohol abuse is common, and implicated in increased severity of withdrawal.

The literature reports an increased risk of benzodiazepine dependence and withdrawal severity among individuals with a paternal history of alcoholism.

Benzodiazepine withdrawal can significantly and adversely affect the course of numerous medical conditions, and so, withdrawal should be avoided—particularly in the acute or surgical setting. Continued benzodiazepine use rarely has acute adverse affects on medical comorbidities. Therefore, while decreasing the dose is an acceptable intervention, clinicians must be cognizant of the increased risks in this vulnerable population.

Elderly patients metabolize benzodiazepines at a significantly reduced rate. This can lead to more severe withdrawal symptoms and worse outcomes. Women are prescribed benzodiazepines twice as often as are men, and are more likely to become dependent. Some evidence supports increased severity of withdrawal in women.

PATIENT EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

Evaluating patients for benzodiazepine cessation requires several steps.

Step 1: Determine the reason the patient is seeking evaluation, and gather the appropriate collateral information necessary to best assess the clinical situation.

Step 2: Take a sedative–hypnotic use history, including dose, duration of use, substance used, and previous treatment interventions as well as treatment responses.

Step 3: Gather information on the history of alcohol and other drug use including past treatment and withdrawal symptoms.

Step 4: Take a thorough psychiatric history including previous diagnoses, hospitalizations, suicide attempts, and treatment. Be sure to ask if alcohol or drugs were used close to the time the diagnoses were made.

Step 5: Take a family history of substance use and psychiatric and medical illnesses.

Step 6: Gather the patient’s medical history

Step 7: Take a psychosocial history

Step 8: Perform a physical and mental status exam.

Step 9: Run a urine drug screen for substances of abuse, and check other laboratory values that are clinically indicated.

Step 10: Complete an individualized assessment focusing on factors that could influence the degree of withdrawal.

Step 11: Come up with a differential diagnosis.

Step 12: Determine the appropriate setting for treatment.

Step 13: Determine the most appropriate treatment method.

Step 14: Obtain informed consent.

Step 15: Begin the detoxification process. Be sure to monitor and adjust the treatment plan as needed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree