and Alena Skalova2

(1)

Departamento de Ciências Biomédicas e Medicina, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal

(2)

Department of Pathology, Medical Faculty Charles University, Plzen, Czech Republic

14.1 Definition, Site and Incidence

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC) is a recently described new distinctive salivary gland tumour defined by specific genetic alteration: the ETV6 gene rearrangement [31]. As the name implies, MASC is characterised by histological and immunohistochemical resemblance to secretory carcinoma of the breast, which is a rare breast cancer occurring mainly but not exclusively in young patients and carrying a favourable clinical outcome [22, 33]. Histologically, both MASC and secretory breast cancer are composed of uniform cells with bland-looking vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic vacuolated cytoplasm, arranged in tubular, microcystic and solid growth patterns with abundant PAS-positive secretions. Furthermore, both tumours are strongly S-100 protein, vimentin, mammaglobin and cytokeratin positive. Moreover, MASC of the salivary glands, similarly as secretory carcinoma of the breast, harbours a recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25) which leads to a fusion gene between the ETV6 gene on chromosome 12 and the NTRK3 gene on chromosome 15 [31, 33].

Inspired by seminal paper [31], several other groups recently reviewed their salivary gland tumour files and found more cases of MASC confirming thus an existence of MASCs of the salivary glands as originally described and showed that expression of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion is a frequent event in these tumours [3, 7–9, 12, 13, 17, 20, 27]. Moreover, eight new cases of MASC have been documented as case reports within the last 2 years [10, 15, 18, 24, 26]. Historically, most MASC were categorised as acinic cell carcinomas (ACC) or adenocarcinomas not otherwise specified [8, 31]. Cytological features of MASC have been reported mimicking those of low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, including sheets of bland epithelial cells and isolated mucinous cells [21], ACC or pleomorphic adenoma [1] and papillary low-grade neoplasms, including papillary ACC [14].

Whilst morphological features of MASC are now well recognised, the clinical significance of distinguishing MASC remains unclear. In terms of clinical outcome, there is no statistically significant difference in disease-free survival and overall survival between MASC and AciCC. There are, however, some differences with respect to site and gender. In contrast to AciCC, MASC has slight male predilection [7, 31]. MASC is more commonly reported in extraparotid sites than AciCC [2]. Regarding clinical behaviour, MASC appears to have greater potential to develop lymph node metastases [7].

14.2 Histopathology

Grossly, the tumours are rubbery, with a white-tan to grey cut surface. Occasionally, on cut surface the tumours may appear cystic, containing yellow-whitish fluid.

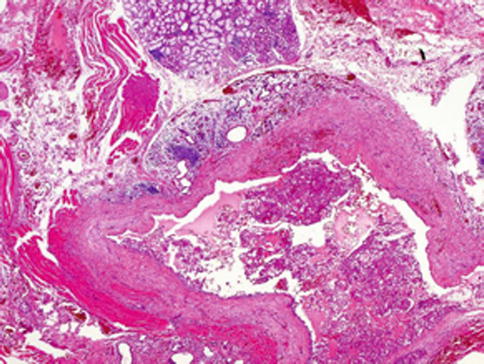

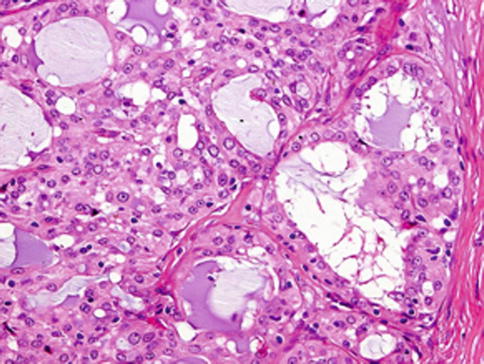

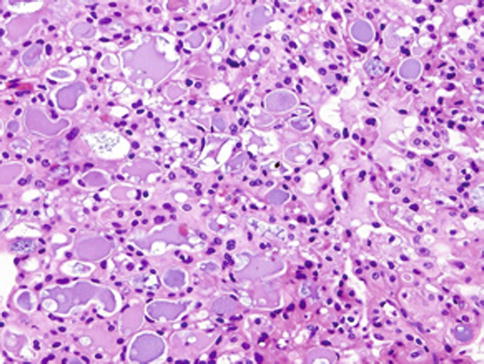

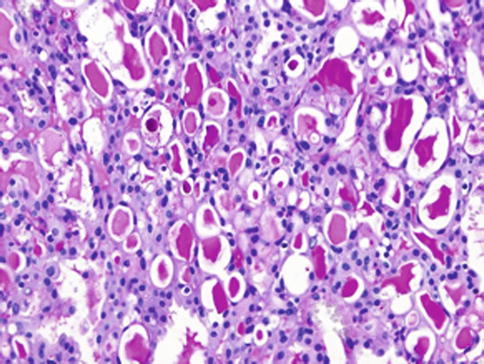

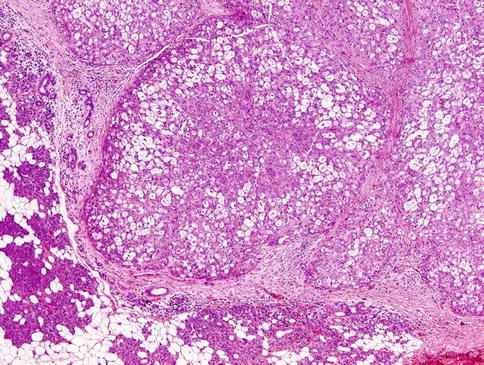

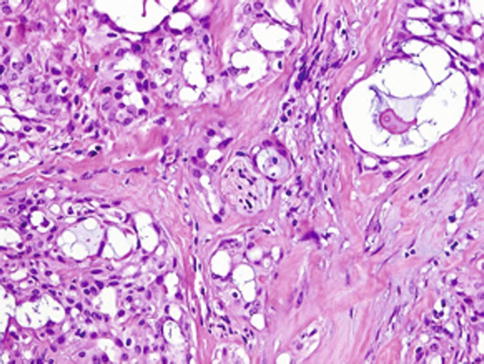

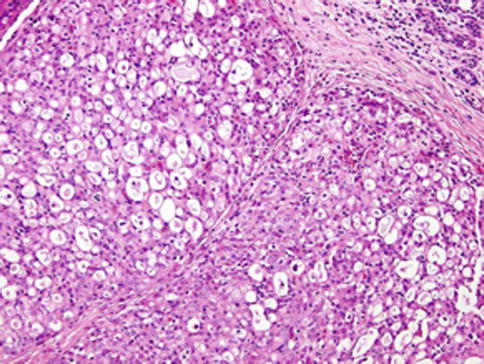

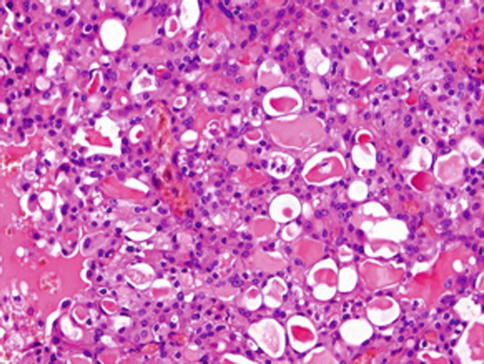

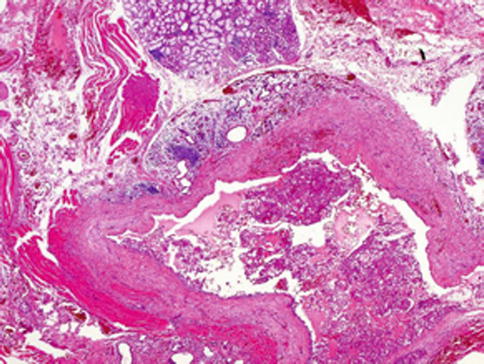

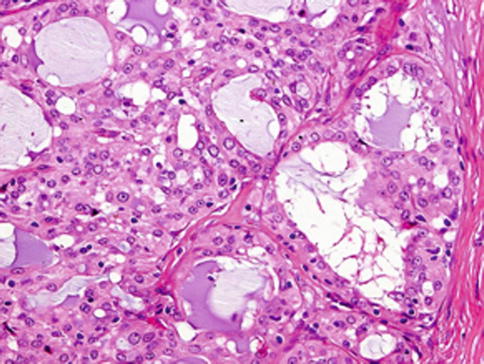

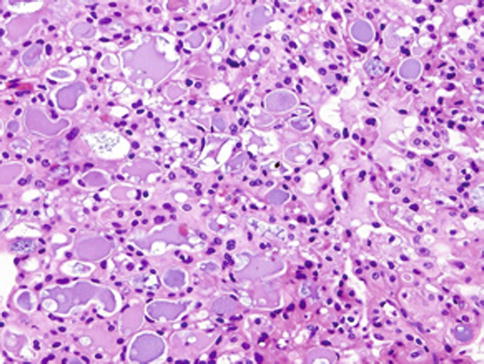

Histologically, the borders of the tumours are usually circumscribed but not encapsulated (Fig. 14.1), and invasion within the salivary gland is often present. Perineural invasion can be sometimes present (Fig. 14.2), but the tumours usually do not have evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Necrosis is typically not identified. The extension to extraglandular tissues can be seen in some cases. Microscopic features of MASC closely mimic intercalated duct cell predominant acinic cell carcinomas. The lesions show a variety of architectural patterns. They often have a lobulated growth pattern divided by fibrous septa. In most cases, MASC is composed of microcystic/solid and tubular structures (Fig. 14.3) with abundant eosinophilic homogeneous or bubbly secretory material (Fig. 14.4) [31]. Less commonly, the tumours are dominated by one large cyst with multilayered lining, which can display tubular, follicular, macro- and microcystic or papillary architecture, with occasional solid areas (Fig. 14.5) [9]. The tumour cells have low-grade vesicular round to oval nuclei with finely granular chromatin and distinctive centrally located nucleoli (Fig. 14.6). The cytoplasm is pale, focally clear to pink with granular or vacuolated quality [31]. Unilocular or multilocular cystic spaces, focal presence of isolated mucinous cells and expression of high molecular weight keratins (HMWK) in some cases of MASC may resemble mucoepidermoid carcinoma [9, 19]. A greater degree of invasion, perineural involvement, oral cavity location and papillary-cystic architecture are also present [2, 9]. Some cases had involvement of ducts, possibly suggesting an origin from ductal epithelial cells [9, 19]. Abundant bubbly secretion is present within microcystic and tubular spaces (Fig. 14.7). The colloid-like secretory material stains positively for periodic acid-Schiff with and without diastase as well as for alcian blue (Fig. 14.8). In contrast to acinic cell carcinoma, serous acinar differentiation is not a feature of MASC, and the cells of MASC are devoid of PAS-positive secretory zymogen cytoplasmic granules.

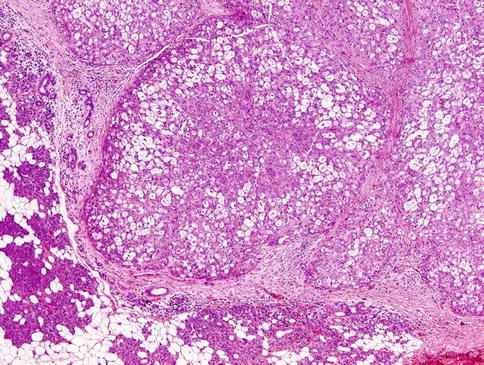

Fig. 14.1

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). The tumours are usually circumscribed but not encapsulated. MASC has lobulated pattern and is surrounded by fibrous pseudocapsule. The parotid gland tissue is seen (left lower)

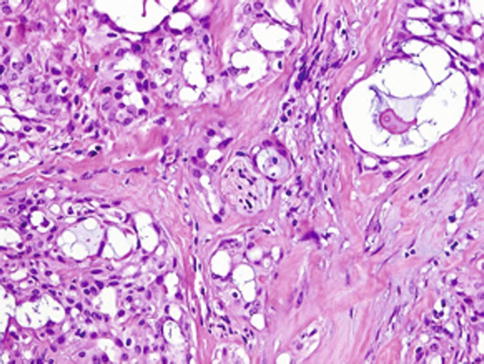

Fig. 14.2

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). Perineural invasion can be sometimes present

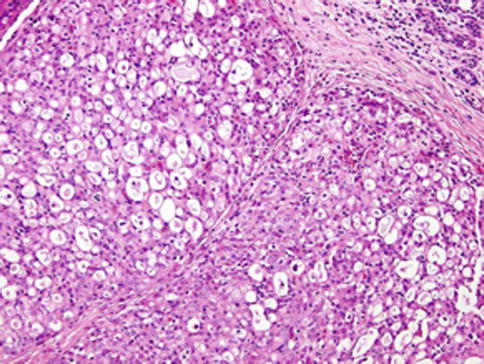

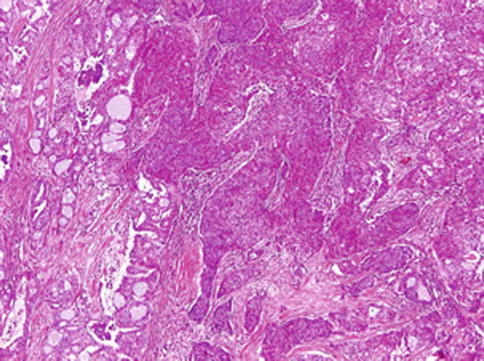

Fig. 14.3

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). MASC is composed of microcystic/solid and tubular structures

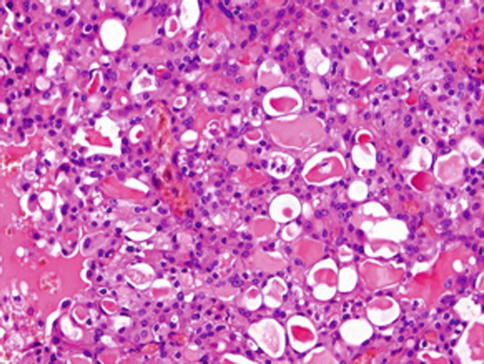

Fig. 14.4

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). Abundant eosinophilic homogeneous or bubbly secretory material is a characteristic feature

Fig. 14.5

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). In minority of cases, the tumours are encapsulated and dominated by one large cyst with multilayered lining

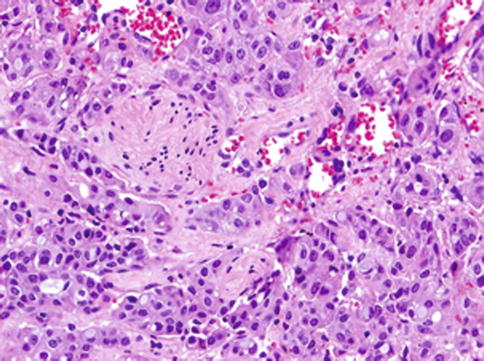

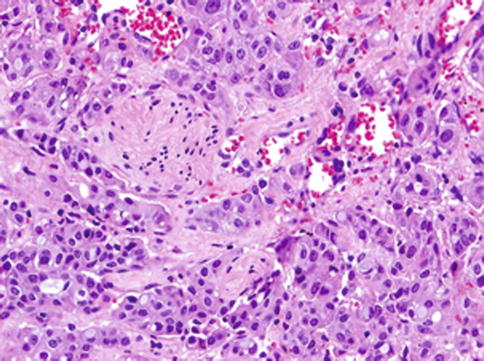

Fig. 14.6

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). The tumour cells have low-grade vesicular round to oval nuclei with finely granular chromatin and distinctive centrally located nucleoli

Fig. 14.7

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). Abundant bubbly secretion is present within microcystic and tubular spaces

Fig. 14.8

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). The colloid-like secretory material stains positively for periodic acid-Schiff with and without diastase as well as for alcian blue

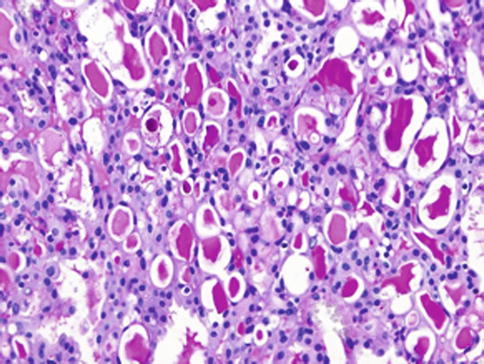

Cellular atypia is usually mild, and mitotic figures are in most cases rare. In three cases of MASC, the high-grade (HG) component appeared as a distinct population of anaplastic cells with high mitotic rate arranged in trabecular and solid growth patterns with common perineural invasion (Fig. 14.9). Irregular-shaped tumour islands with large geographic comedo-like necrosis infiltrated desmoplastic stroma (Fig. 14.10). In contrast to the low-grade component of conventional MASC, the tumour cells of the HG component display apparent nuclear polymorphism and distinctive nucleoli, and they fail to reveal any secretory activity (Fig. 14.11). Invasion of the skin was observed in all three cases [30].

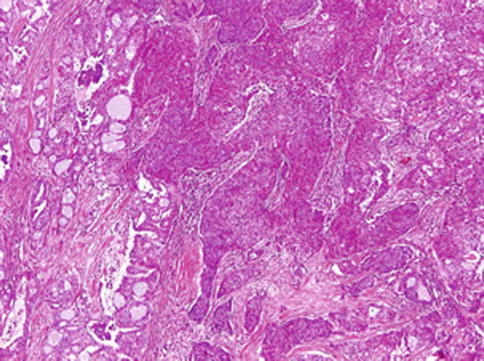

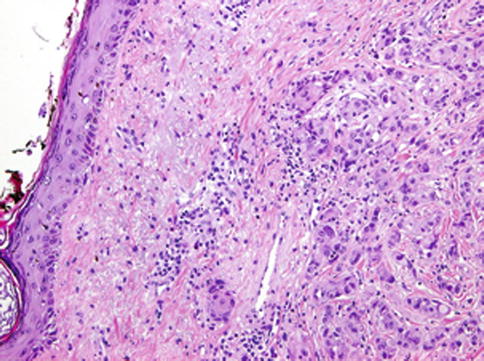

Fig. 14.9

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma with high-grade transformation (HG-MASC). The tumour is composed of two distinct patterns sharply delineated. The high-grade (HG) component appears as a distinct population of anaplastic cells with high mitotic rate arranged in trabecular and solid growth patterns

Fig. 14.10

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma with high-grade transformation (HG-MASC). The tumours reveal an invasive growth pattern and perineural invasion is apparent

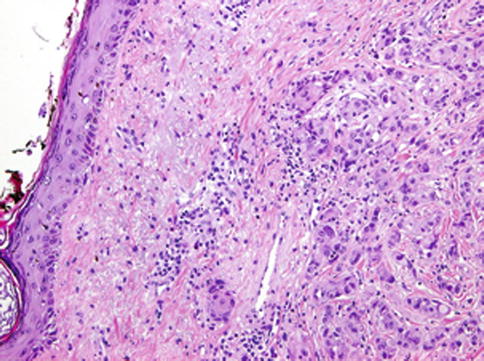

Fig. 14.11

Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma with high-grade transformation (HG-MASC). Tumour cells of the HG component display apparent nuclear polymorphism, they have distinctive nucleoli and they fail to reveal any secretory activity. Invasion of the skin is seen

14.3 Molecular Pathology

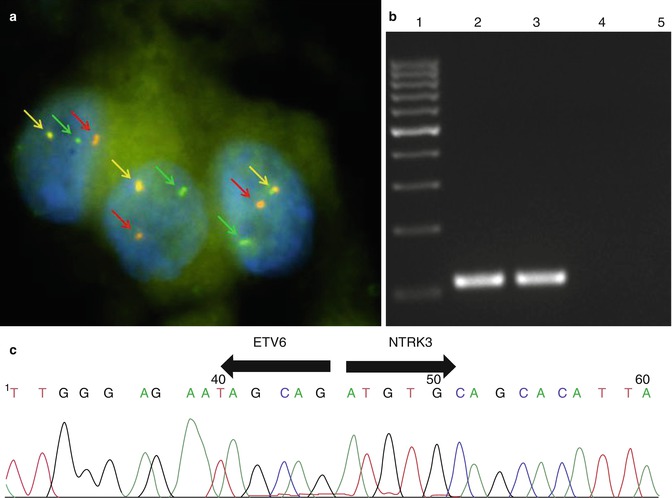

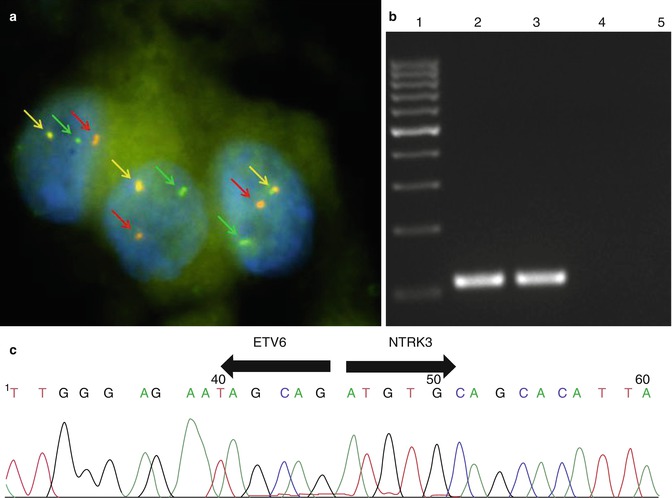

MASC of salivary glands, similarly as secretory carcinoma of the breast, harbours a recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25) which leads to a fusion gene between the ETV6 gene on chromosome 12 and the NTRK3 gene on chromosome 15 (Fig. 14.12). The biological consequence of the translocation is the fusion of the transcriptional regulator (ETV6) with membrane receptor kinase (NTRK3) that activates kinase through ligand-independent dimerisation and thus promotes cell proliferation and survival. The presence of ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene has not been demonstrated in any other salivary gland tumour so far. The ETV6-NTRK3 translocation is not entirely specific for MASC, as it has been identified in a range of neoplasms including congenital fibrosarcoma, congenital cellular mesoblastic nephroma and acute myeloid leukaemia [34]. Moreover, in the context of breast malignancies, the presence of ETV6-NTRK3 translocation seems to be restricted to secretory breast cancer [33]. Similarly, ETV6-NTRK3 translocation has not been detected in any salivary gland tumour other than MASC so far.

Fig. 14.12

MASC harbours a recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25) which leads to a fusion gene between the ETV6 gene on chromosome 12 and the NTRK3 gene on chromosome 15. (a) Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) using LSI ETV6 (TEL) (12p13) Dual Color, Break Apart Rearrangement Probe (VYSIS/Abbott Molecular). Green and red arrows show split signals indicating break of ETV6 gene. Yellow arrows show nonaltered chromosome. (b) Expression of ETV6-NTRK3 fusion transcript detected by RT-PCR. 1 marker, 2 positive MASC sample, 3 positive amplification control, 4 negative amplification control, 5 non-template control. (c) Sequence analysis of ETV6-NTRK3 fusion transcript. Arrows show the translocation breakpoint

14.4 Immunohistochemical Findings

All MASCs show diffuse and strong CK7, CK8, CK18, S-100 protein and vimentin staining. In addition, in most cases there is significant positivity for CK19 (11/12), gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP-15) (8/11) and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (9/11). The tumour cells also showed strong positive expression of STAT5a and mammaglobin in all tested cases. Basal cell/myoepithelial cell markers, such as p63, calponin, CK14, smooth muscle actin and CK5/6, are negative in vast majority of cases [31]; however, in some other cases, the p63 protein antibody did highlight an incomplete rim of non-neoplastic cells surrounding the tumour cells. Most of the tumours showed this finding only focally, with the majority of the tumour not being intraductal [9, 19]. All cases were negative for calponin, smooth muscle actin and CK14. Proliferative activity was variable with MIB1 indices ranging between 5 and 28 % in most cases [19, 31]. All cases of MASC are positive for mammaglobin; the staining is strong and diffuse in both the cytoplasm and intraluminal secretory material [3, 31]. Diffuse and strong mammaglobin and S-100 protein immunoreactivity are used to differentiate MASC from its histomorphological mimics, in particular acinic cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma NOS. However, co-expression of mammaglobin and S-100 protein can be seen in many salivary gland tumours other than MASC, especially in adenoid cystic carcinoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma [23], but none of these MASC mimics are positive for the ETV6 translocation characteristic for diagnosing of MASC.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree