Malt Lymphoma

Scott R. Owens, MD

Key Facts

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Most gastric MALT lymphomas associated with gastritis caused by Helicobacter pylori infection

Clinical Issues

85% of all GI MALT lymphomas in stomach

Majority present with low-stage disease (I-II)

H. pylori eradication therapy 1st-line treatment for gastric MALT

Most (as many as 80% of gastric cases) respond to H. pylori eradication with regression of lymphoma

Cases with t(11;18)(q21;q21) resistant to H. pylori eradication therapy

Up to 50% of primary gastric lymphomas are MALT lymphoma

Microscopic Pathology

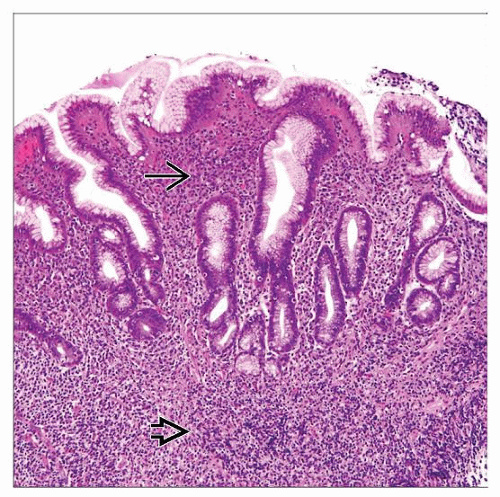

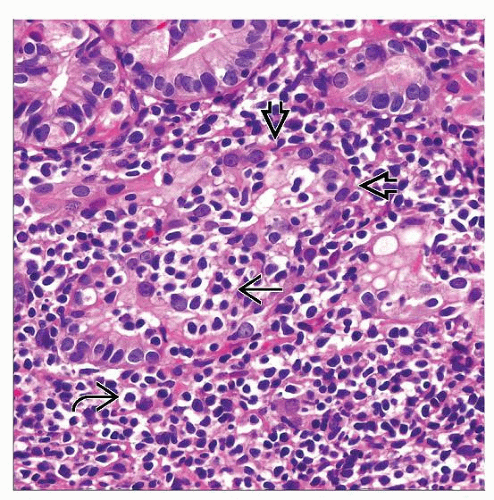

Neoplastic lymphocytes recapitulate “marginal zone” of reactive follicle

Plasmacytic differentiation seen to some extent in ˜ 1/3 of cases; occasionally predominant cell type

Lymphoepithelial lesions highly characteristic of (but not specific for) MALT lymphoma

Top Differential Diagnoses

H. pylori gastritis

Distinction of severe gastritis from early MALT lymphoma often very challenging

Diagnostic Checklist

Lymphomas composed of predominantly large cells should be diagnosed as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (not high-grade MALT lymphoma)

TERMINOLOGY

Abbreviations

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma

Synonyms

Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (EMZL) of MALT

Definitions

Low-grade lymphoma composed of various types of predominantly small B lymphocytes

Small- to intermediate-sized centrocyte-like cells

Monocytoid cells

Large, centroblast- or immunoblast-like cells

Plasma cells

ETIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS

Infectious Agents

Most gastric MALT lymphomas associated with gastritis caused by Helicobacter pylori infection

H. pylori strains with CagA gene are most immunogenic

H. pylori organisms difficult to find as process evolves from gastritis to lymphoma

Serologic studies for H. pylori antibodies may be helpful

Evidence suggests association of extragastric MALT lymphomas with H. pylori as well

Immunoproliferative small intestinal disorder (IPSID)

Subtype of MALT lymphoma related to infection with Campylobacter jejuni

Antigenic Stimulation

Chronic antigen exposure → acquisition or expansion of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

Termed “acquired” MALT

Contains well-developed lymphoid follicles/germinal centers with surrounding lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate

In contrast to “native” MALT, such as Peyer patches in distal ileum

Continued antigenic stimulus → further expansion of B-cell population

Possible clonal expansion → lymphoma

Process thought to be driven by activated T cells

CLINICAL ISSUES

Epidemiology

Incidence

7-8% of all B-cell lymphomas

Age

Median 61 years

Gender

M:F = 1:1.2

Ethnicity

IPSID occurs in patients in subtropical and tropical locales

Site

GI tract most common site of MALT lymphoma

Up to 50% of primary gastric lymphomas are MALT lymphoma

85% of all GI MALT lymphomas in stomach

Isolated duodenal involvement uncommon

May be involved in conjunction with gastric lymphoma

Small intestinal involvement often multifocal

Distal small intestine (ileum) more frequently involved than proximal (may reflect larger native MALT population in ileum)

May involve wall circumferentially over long segments or create large, discrete mass

Obstruction uncommon as infiltrate not associated with desmoplastic stromal response

Colonic involvement relatively rare (cecum and rectum most frequent)

Other sites of extranodal involvement (e.g., elsewhere in GI tract) relatively common in gastric MALT (about 25%)

Presentation

Abdominal pain

Ulcer

Deep mass

Weight loss

Endoscopic Findings

May be difficult to distinguish from severe gastritis, especially in early cases

Cases without significant endoscopic findings difficult to follow after treatment

Mass

Ulcer

Thickened mucosal folds &/or diffuse wall thickening

Laboratory Tests

H. pylori serology

Serum protein electrophoresis

Natural History

Majority present with low-stage disease (I-II)

Bone marrow involvement uncommon at presentation

Treatment

Options, risks, complications

H. pylori eradication therapy 1st-line treatment for gastric MALT

Involves regimen of multiple medications, including antibiotics

Resolution of lymphoma can take months (up to 24 months reported)

Evidence that certain extragastric MALT lymphomas may respond to this therapy as well

More aggressive 2nd-line therapies should be reserved for truly refractory cases

Adequate time must be given for resolution

Response of lymphoma on follow-up biopsy specimens should not be anticipated for several months

IPSID may respond to broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy

Surgical approaches

Resection not usually performed

Multifocality and diffuse nature of infiltrate makes complete resection difficult

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree