Chapter Forty-Three. Malposition and cephalic malpresentations

Occipitoposterior position of the vertex

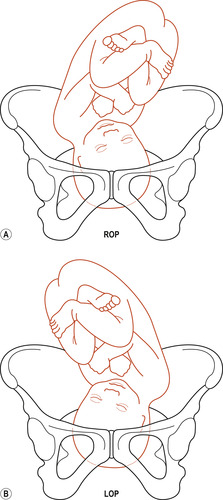

In occipitoposterior position of the vertex, the occiput occupies one of the two posterior quadrants of the mother’s pelvis and the sinciput points towards the opposite anterior quadrant (Fig. 43.1). Malposition is common and affects about 10% of all labours. The outcome of such labours is generally normal with rotation of the occiput to the anterior and normal vertex delivery. However, there may be prolonged labour and mechanical difficulties associated with the delivery.

|

| Figure 43.1 Right and left occipitoposterior positions. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Causes

There is no single satisfactory cause for occipitoposterior position. However, if the forepelvis is small, as found in android and anthropoid pelves, the head may take up a posterior position. Other possible causes include a pendulous abdomen, a flat sacrum or an anterior placenta (Lewis 2004).

Attitude

Instead of the normal well-flexed attitude with the limbs and head flexed on the trunk and the rounded back pointing towards the mother’s soft abdominal wall, the fetal spine faces the forward curve of the maternal lumbar spine and good flexion is not possible. The fetal spine is straightened, the head is held in a deflexed position known as the ‘military position’ and the anterior fontanelle is found directly over the internal os. The term ‘bregmatic presentation’ is sometimes used (Lewis 2004). This position of the head brings larger diameters into relationship with the pelvic brim and engagement of the head may not occur.

Risks

• Obstructed labour if either deep transverse arrest or brow presentation result.

• Maternal perineal trauma such as a third-degree tear and bruising.

• Cord prolapse if there is early spontaneous rupture of the membranes and ill-fitting presenting part.

• Neonatal cerebral haemorrhage due to upward moulding of the fetal skull. The falx cerebri may be pulled away from the tentorium cerebelli, resulting in a tear of the great vein of Galen.

• Chronic fetal hypoxia, if present, results in venous distension, which increases the likelihood of haemorrhage.

Diagnosis in pregnancy

Occipitoposterior position is the most common cause of a non-engaged head in late pregnancy in primigravidae. The woman may complain that the baby has too many hands and feet and that she has to pass urine more frequently in the absence of infection (El Halta 1996). Abdominal examination will confirm the diagnosis:

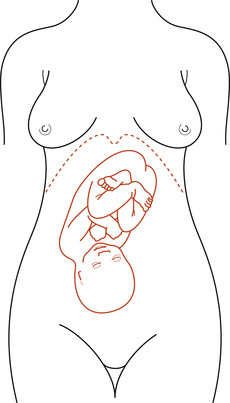

• On inspection: the abdomen appears flattened. There may be a saucer-shaped depression below the umbilicus between the fetal head and limbs (Fig. 43.2A).

|

| Figure 43.2 (A) Abdominal contour with occipitoposterior position, showing depression at umbilicus. (B) Rounded abdominal contour with occipitoanterior position. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

• On palpation: the fetal head is high and deflexed. It may feel large if the occiput is more lateral but small if the occiput is quite posterior and the bitemporal diameter is palpated. Fetal limbs may be felt on both sides of the midline of the uterus and the fetal back may be felt out in the flank (Fig. 43.3).

|

| Figure 43.3 In occipitoposterior positions the anterior shoulder is well out from the midline and fetal limbs are readily palpable. This may cause a mistaken diagnosis of multiple pregnancy. (From Beischer N A, Mackay E V 1986 Obstetrics and the Newborn. Baillière Tindall, London, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

• On auscultation: the fetal heart may be heard at or just above the umbilicus or out in one flank.

Diagnosis in labour

Abdominal examination, as described above, will indicate the presence of an occipitoposterior position although the head may be flexed and become engaged.

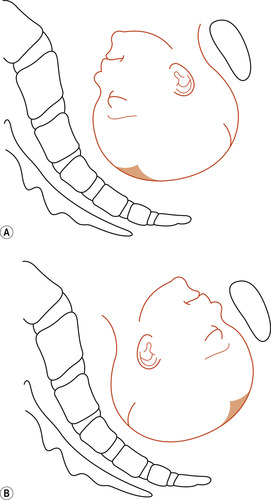

On vaginal examination, palpation of the anterior fontanelle is a diagnostic aid in determining occipitoposterior position (ALSO 2005). If the head is reasonably well flexed, the anterior fontanelle will be felt anteriorly and it may be possible to feel the posterior fontanelle. When the head is deflexed, the anterior fontanelle is almost central and easy to feel by its shape and size (Fig. 43.4B).

|

| Figure 43.4 Position of the anterior and posterior fontanelles. (A) Occipitoanterior. (B) Occipitoposterior. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

The first stage of labour

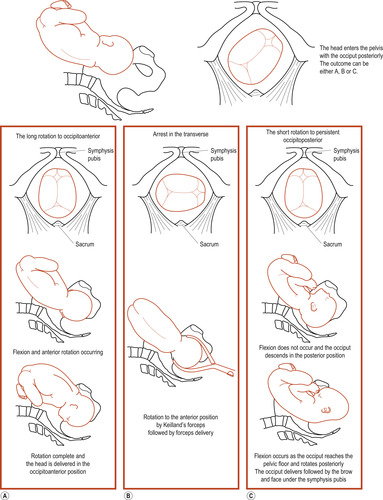

Fetal malposition of occipitoposterior is associated with more painful, prolonged and obstructed labour and a difficult delivery (Hunter et al 2007). The course of labour partly depends on the degree of descent and flexion that takes place (Fig. 43.5). This in turn is influenced by the strength of uterine contractions. If the head flexes, it is likely that labour will proceed normally. The engaging diameter is the suboccipitofrontal (10 cm). When the occiput reaches the pelvic floor and rotates  ths of a circle, the baby is born with the occiput anterior.

ths of a circle, the baby is born with the occiput anterior.

ths of a circle, the baby is born with the occiput anterior.

ths of a circle, the baby is born with the occiput anterior. |

| Figure 43.5 Outcome of an occipitoposterior position. The head enters the pelvis with the occiput posteriorly. The outcome can be A, B or C. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

If the head remains deflexed, problems may arise. The engaging diameter is the occipitofrontal (11.5 cm). The head may be non-engaged at the commencement of labour and early rupture of the membranes may occur. If the presenting part is high and not well applied to the cervix, there is a risk of cord prolapse.

Labour is prolonged because of poor stimulation of the cervix and dilation is slow and uneven. Contractions may be excessive but uncoordinated and painful and the woman experiences severe backache. Encouraging the mother to take up a knee–chest position for 45 min may help rotation of the vertex to an anterior position (El Halta 1996). Augmentation of labour may be necessary (see Chapter 41). Care must be taken to prevent maternal loss of confidence, ketosis and dehydration and fetal distress. There may be difficulty in micturition with retention of urine and the woman needs encouragement to empty her bladder frequently. Catheterisation may be necessary if the woman is unable to pass urine.

The role of maternal position

Hunter et al (2007) discuss the benefits of upright and leaning-forward postures in order to encourage the fetal head to engage in the optimal occipitoanterior position. Avoidance of a reclining position with the knees higher than the hips will reduce the incidence of occipitoposterior position of the fetal head at the commencement of labour (Sutton 2001). Taking up an all-fours posture may reduce the pressure of the fetus on the maternal spine and help to reduce backache. It may also aid rotation of the fetus to an occipitoanterior position (Simkin & Ancheta 2005).

It has been suggested that in the antenatal period if a woman adopts a hands-and-knees posture leaning forward then this might promote a favourable position of the baby (Hunter et al 2007). Three trials (2794 women) were included in a systematic review (Hunter et al 2007) to explore this issue. Two trials were focused on the antenatal period. In one trial (100 women), four different postures (four groups of 20 women) were combined for comparison with the control group of 20 women. Findings were that in the lateral or posterior position the presenting part of the fetus was less likely to persist following 10 min in the hands-and-knees position compared to a sitting position. In a second trial (2547 women), advice to assume the hands-and-knees posture for 10 min twice daily in the last weeks of pregnancy had no effect on the baby’s position at delivery or on any of the other pregnancy outcomes.

Simkin & Ancheta (2005) detail the advantages of ambulation and forward-leaning positions in labour. Freedom to move around in the first stage of labour and the maintenance of an upright position such as can be achieved by sitting astride a chair and leaning on its back have been shown to be beneficial to women with an occipitoposterior presentation. Descent of the fetal head is encouraged and good uterine contractions should follow. Progress is more likely to be normal, culminating in long internal rotation of the occiput (see below). In the second stage of labour, the squatting position increases the anteroposterior diameter of the outlet and may aid rotation, descent and delivery.

The third trial in the systematic review of Hunter et al studied the use of hands-and-knees position in labour. The sample comprised 147 labouring women at 37 or more weeks’ gestation, where the fetal occipitoposterior position was confirmed by ultrasound. Randomisation occurred: 70 women (intervention group) assumed hands-and-knees positioning for a period of at least 30 min compared to 77 women (control group) who did not assume hands-and-knees positioning in labour. There was no statistical significance in the reduction of occipitoposterior or transverse positions at delivery and operative deliveries. However, there was a significant reduction in back pain. The authors conclude from the evidence in the systematic review (Hunter et al 2007) that adopting these positions as a recommended intervention could not be endorsed. However, they stated that if the women find these positions comfortable then they should adopt them and especially in labour where maternal backache is reduced.

Relieving backache

To relieve the backache, many women find the kneeling position beneficial. This position may also aid rotation of the head to an occipitoanterior position. Massaging the woman’s back in the lumbosacral region may also help to relieve the backache and a warm bath has been found to be helpful. Epidural analgesia is the most effective method of relieving the pain. In the second stage of labour, perineal trauma is minimised by an upright position (Aasheim et al 2007).

A difficult problem for the woman in the late first stage of labour is feeling a strong urge to push before full cervical dilatation. Pushing presses the fetal head against the cervix and oedema may occur, thus lengthening the transitional stage of labour. Simkin & Ancheta (2005) suggest that the adoption of the kneeling position with the head resting on the forearms may lessen the pressure on the cervix.

The second stage of labour

The five main possible outcomes of an occipitoposterior position are:

1. Long internal rotation of the occiput and delivery as an occipitoanterior.

2. Deep transverse arrest of the head.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree