(1)

Department of Pathology, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast, UK

Abstract

Cervical adenocarcinomas are increasing in incidence and now account for approximately 25 % of cervical carcinomas in most developed countries. Most are associated with high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and are of the usual endocervical type. However, a minor proportion of unusual morphological subtypes of cervical adenocarcinoma are not HPV associated. This chapter covers the clinicopathological features of the various subtypes of cervical adenocarcinoma.

Keywords

CervixAdenocarcinomaHuman papillomavirusIntroduction

As discussed in the Chap. 3, premalignant and malignant endocervical glandular lesions are increasing in incidence with adenocarcinomas now accounting for approximately 25 % of cervical carcinomas in most developed countries [1]. The mean age of patients with cervical adenocarcinoma in most series is between 44 and 54 years. Several morphological subtypes of cervical adenocarcinoma are recognized in the 2003 World Health Organization (WHO) classification [2] (modification in Table 4.1). Of these, by far the most common is the endocervical (or usual) type of mucinous adenocarcinoma which accounts for approximately 80 % of cervical adenocarcinomas. Some recently recognized subtypes of primary cervical adenocarcinoma, such as gastric type, are not currently recognized by the WHO but are discussed in this chapter. Although the association is less strong than with cervical squamous carcinoma, the majority of cervical adenocarcinomas are associated with high risk HPV, most commonly types 16 and 18; HPV 18 is proportionally more common than with invasive squamous carcinomas [3–9]. However, unusual morphological subtypes of cervical adenocarcinoma, such as adenoma malignum, gastric type, mesonephric and clear cell are mostly unrelated to HPV [3–6]. While diffuse p16 positivity has been regarded as a surrogate marker of the presence of high risk HPV, non-HPV related cervical adenocarcinomas may also be positive with this marker, although staining is usually focal rather than diffuse [3, 4].

Table 4.1

Modification of World Health Organization (WHO) classification of cervical adenocarcinomas [2]

Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

Endocervical (usual) type |

Intestinal |

Signet-ring cell |

Minimal deviation |

Villoglandular |

Gastric type (not included in WHO Classification) |

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma |

Clear cell adenocarcinoma |

Serous adenocarcinoma |

Mesonephric adenocarcinoma |

Early invasive adenocarcinoma |

Other epithelial tumours |

Adenosquamous carcinoma |

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (not included in WHO classification) |

Glassy cell carcinoma |

Adenoid cystic carcinoma |

Adenoid basal carcinoma |

Carcinosarcoma |

Mixed |

Metastatic |

Early Invasive Adenocarcinoma

Early invasive adenocarcinoma of the cervix is increasingly being diagnosed. While some of this increase may reflect the rising incidence of cervical adenocarcinoma in general or earlier detection due to improvements in cervical screening programmes, there is also probably better recognition by histopathologists of the features of early invasion in premalignant cervical glandular lesions; the features of early invasion may be subtle. It is recommended that the term microinvasive carcinoma is not used (for cervical squamous carcinomas, adenocarcinomas and other epithelial tumour types) but rather the tumour should be measured accurately and the appropriate FIGO stage provided. This is because the term microinvasive carcinoma does not appear in the FIGO staging system for cervical cancer [10]. Furthermore, the term microinvasive carcinoma has different in different places. In the United Kingdom, microinvasive carcinoma is considered to be synonymous with FIGO stage IA1 and IA2 disease in some institutions while in others the term is restricted to FIGO stage IA1 tumours. In the United States, the term is largely synonymous with stage IA1 disease. The Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) has its own definition of microinvasive carcinoma which includes lesions up to a depth of 3 mm with no limit on the size of horizontal spread; neoplasms with lymphovascular invasion are excluded [11]. In order to avoid confusion, the British Association of Gynaecological Pathologists Working Group has recommended in the Royal College of Pathologists Dataset for Histological Reporting of Cervical Neoplasia a preference for avoiding the term microinvasive carcinoma and for using the specific FIGO stage as a descriptor [12, 13].

Morphological Features of Early Invasive Adenocarcinoma

Early invasion is, in general, more difficult to recognise in cervical glandular than squamous lesions and it is likely that there is significant interobserver variability in the diagnosis of early invasive adenocarcinoma. This is because there is often an admixture of cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia (CGIN) and adenocarcinoma and sometimes it is not straightforward to ascertain whether invasion is present and where CGIN ends and early invasion starts. This also makes accurate measurement of early invasive adenocarcinoma problematic (discussed below). However, there are a number of morphological features which help to distinguish CGIN from invasive adenocarcinoma [14, 15]. Simplistically, the distinction between CGIN and adenocarcinoma is based on the glandular architecture being too complex in the latter to conform to the normal endocervical glandular field; however, this in itself can be problematic in that the “normal” endocervical glandular architecture may be complex. It should also be recognised that, although rare, CGIN may involve a pre-existing benign endocervical glandular lesion, for example microglandular hyperplasia, where the architecture may be complex and this can result in obvious diagnostic difficulties.

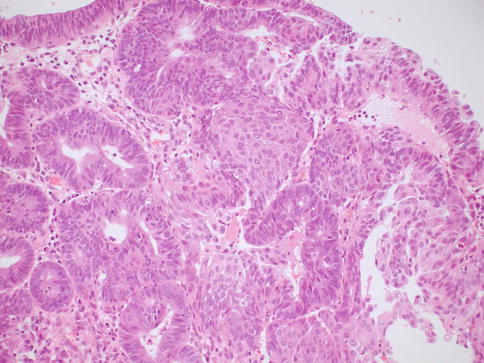

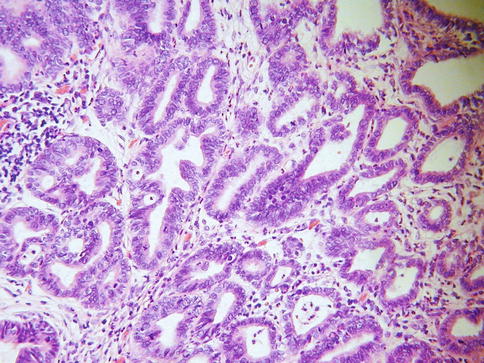

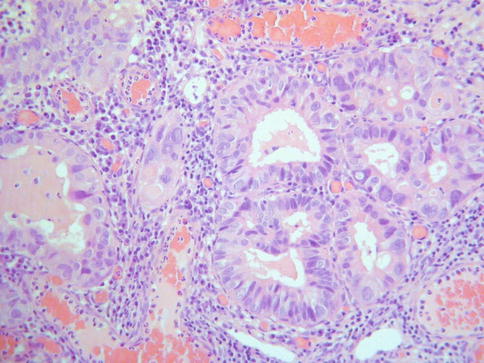

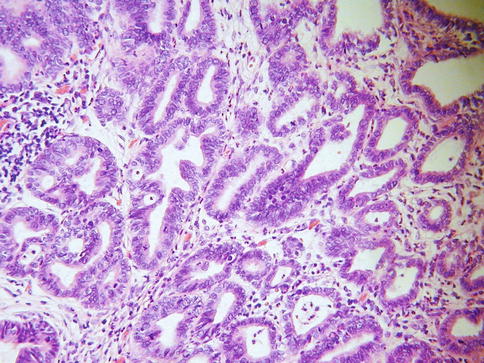

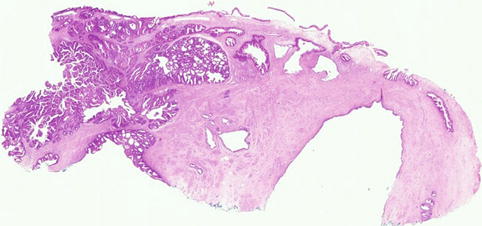

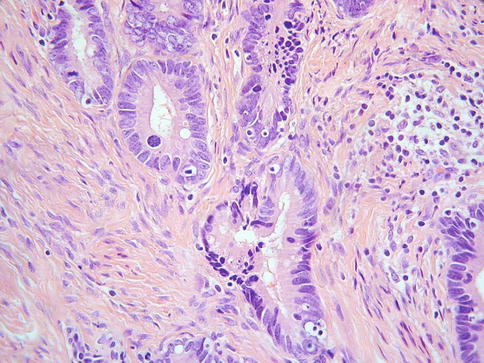

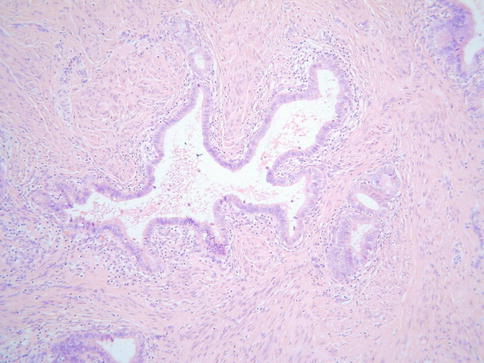

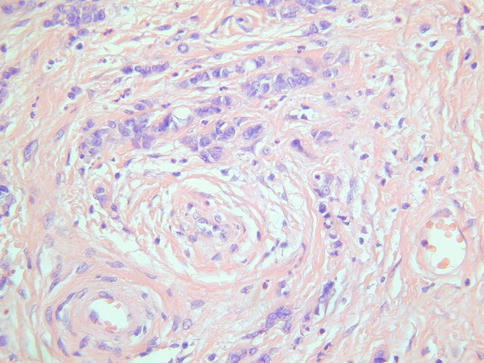

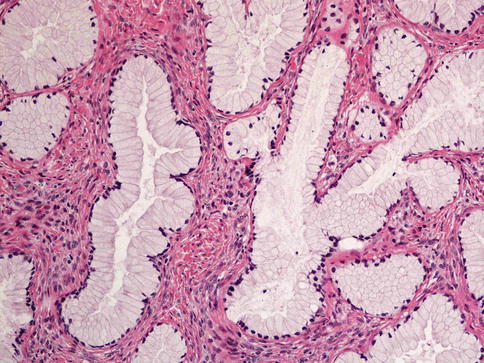

In some cases, although the adenocarcinoma is small there is an obvious infiltrative growth pattern which is often best appreciated on low power with irregular angulated or “crab-like” glands infiltrating the stroma with or without an associated desmoplastic, oedematous or inflammatory reaction (Fig. 4.1). This infiltrative pattern contrasts with CGIN where there is preservation of the normal lobular architecture, although the lobular architecture may be “accentuated”. There are other cases where, although there is no obvious infiltrative growth pattern or stromal reaction, a diagnosis of invasion is made on the sheer glandular architectural complexity which is beyond that compatible with the normal endocervical glandular field (Fig. 4.2). In such cases, there are often papillary, cribriform, labyrinthine and solid growth patterns [14, 15]. Although minor papillary and/or cribriform areas may be present in CGIN, any appreciable amount of papillary or cribriform architecture should suggest adenocarcinoma. Another morphological pattern of early invasion is the presence of small buds, glands or solid nests of cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (squamoid appearance) that emanate from glands involved by obvious CGIN (Fig. 4.3) [16]. This “squamoid” change is analogous to that often seen with early invasive squamous carcinoma. The cells with a squamoid appearance often have enlarged nuclei with prominent nucleoli and may be surrounded by an inflammatory reaction. Close proximity of abnormal glands to thick-walled stromal blood vessels may also be useful in helping to confirm an invasive lesion (Fig. 4.4), especially in cases where there is little in the way of a stromal response [17]. A stromal inflammatory, oedematous or desmoplastic response is not always apparent in early invasive adenocarcinomas, or indeed in some overt adenocarcinomas, but may be useful when present. However, it should be noted that the glands of CGIN may be surrounded by an inflammatory or oedematous stroma; as such, a true desmoplastic stromal reaction is more useful in diagnosing invasion than inflammation or oedema. Lymphovascular space invasion may be seen but is relatively uncommon in early invasive adenocarcinomas [18].

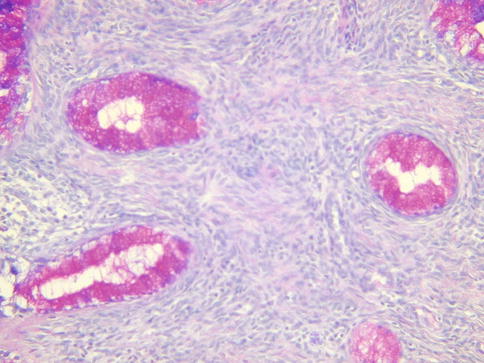

Fig. 4.1

Small adenocarcinoma with an obvious infiltrative growth pattern

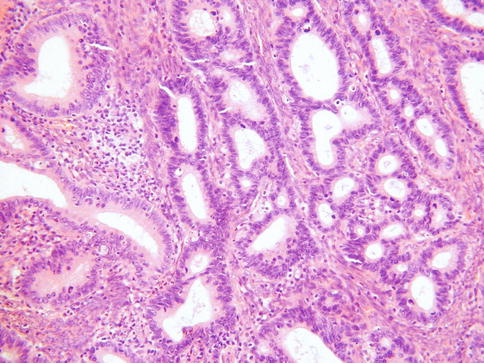

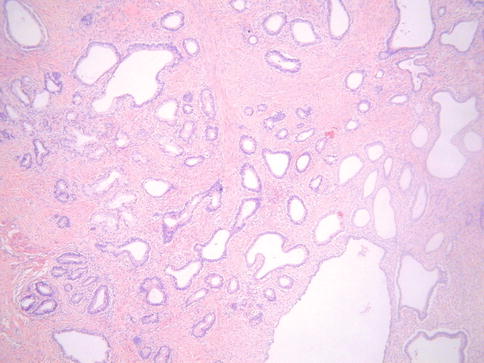

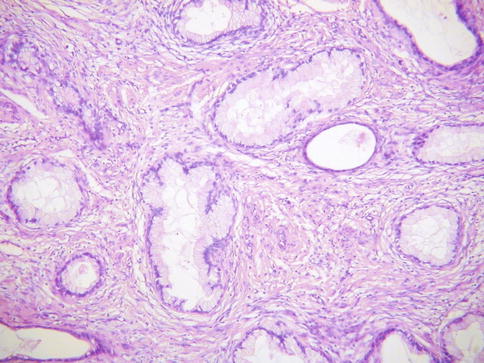

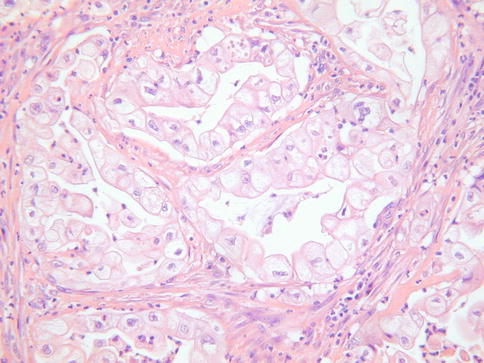

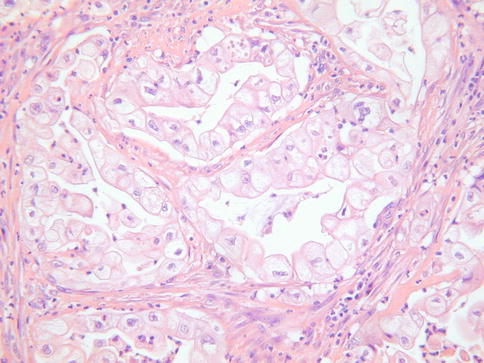

Fig. 4.2

Cervical adenocarcinoma where there is no obvious infiltrative growth pattern but the overall architecture is too complicated to conform to the normal endocervical glandular field

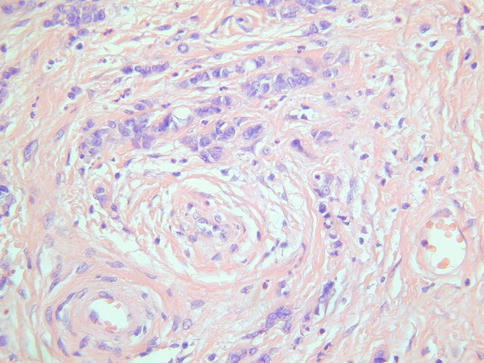

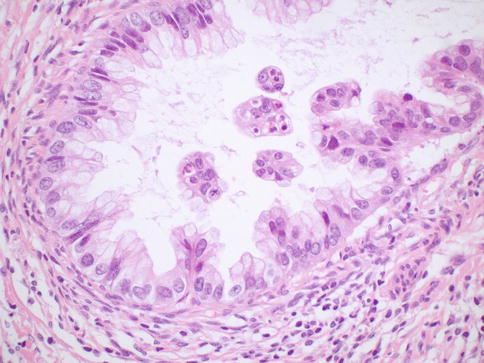

Fig. 4.3

Early invasive adenocarcinoma where small buds of cells with a squamoid appearance emanate from glands involved by CGIN

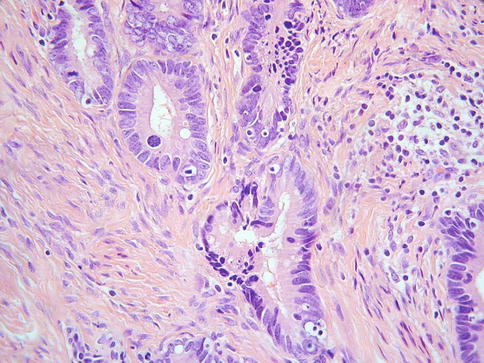

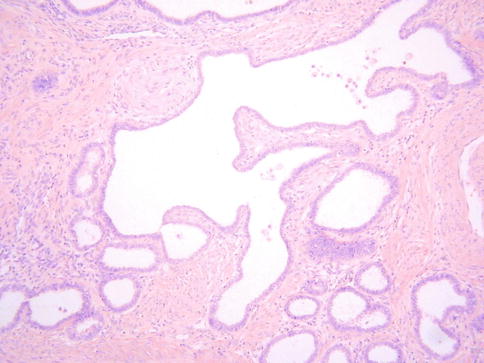

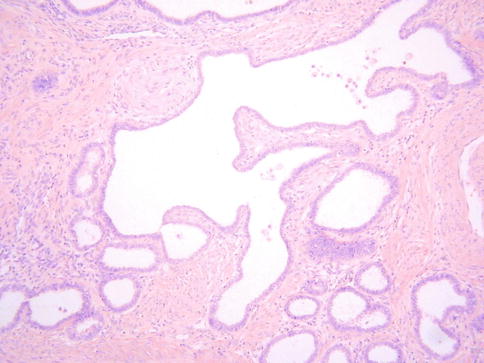

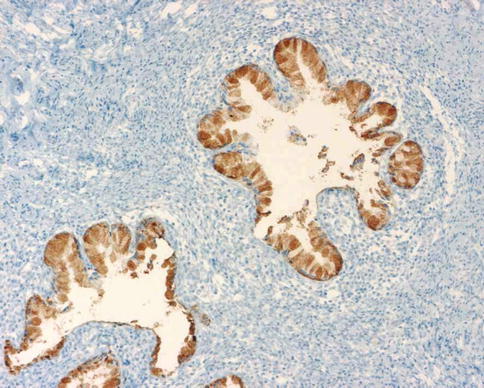

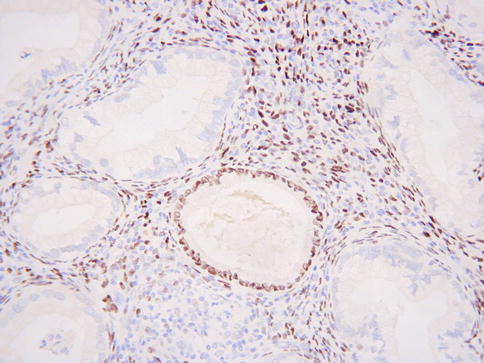

Fig. 4.4

Close proximity of glands to thick walled stromal blood vessels may be helpful in confirming an invasive adenocarcinoma

In general, immunohistochemistry is of little value in the diagnosis of early invasion in cervical glandular lesions. The value of basement membrane markers, such as laminin and type IV collagen, has been investigated but, although the results of various studies are somewhat contradictory [19, 20], these markers are of limited use in individual cases. Although the basement membrane is generally uniform and intact in CGIN (diffuse expression of these markers) and focally deficient in early invasive adenocarcinoma (focal loss of these markers), there are exceptions in that these proteins may be focally lost in some cases of CGIN and conversely invasive adenocarcinomas, even in lymph node metastases, may produce them. One study found that α smooth muscle actin was of some value in the distinction between CGIN and invasive adenocarcinoma in that there is an increase in staining surrounding invasive glands, probably secondary to stromal desmoplasia [21]; however, this marker is unlikely to be of value in individual problematic cases.

Measurement of Early Invasive Adenocarcinoma

The measurement of small invasive adenocarcinomas may be extremely difficult because of the problems in recognising early invasion and in ascertaining which foci constitute CGIN and which represent invasion. It cases where there is doubt, it is best to err on the side of caution and measure the whole of the lesion which is considered to possibly represent invasion. The depth of invasion of a cervical carcinoma is generally measured from the deepest point of invasion to the basement membrane of the surface or crypt epithelium from which the tumour arises. However, this may be extremely difficult with glandular lesions and, especially in cases where a diagnosis of invasion is made on the presence of extreme architectural complexity, measurement should be from the surface to the deepest aspect of the lesion; as such, tumour thickness rather than depth of invasion is measured in these cases and it is recognised that this may overestimate the depth of invasion [22]. The lesion should also be measured from one lateral extent to the other on the slide on which the extent is greatest and, as with other carcinomas, the third dimension is calculated by multiplying the number of blocks involved by the thickness of the blocks (calculated from the macroscopic description of the specimen). As with squamous lesions, there may be difficulties in measuring cases with multifocal or possible multifocal invasion, although multifocal invasion appears more uncommon in cervical adenocarcinomas than squamous carcinomas. If the multiple foci of invasion are clearly separate, these can be regarded as multifocal early invasive adenocarcinomas. In such cases, each individual focus of invasion is measured rather than the width of the whole lesion. However, as stated, this is relatively uncommon in adenocarcinomas and, if the foci are not clearly separate, the width of the whole lesion should be taken as the horizontal measurement [12].

FIGO stage 1A adenocarcinoma cannot be diagnosed in an incompletely excised lesion with CGIN or adenocarcinoma at a margin. With a small adenocarcinoma which is completely excised by LLETZ or cone, the closest margin should be stated and the distance of the adenocarcinoma and CGIN from the margin provided on the pathology report. The presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion should also be documented.

Management of Early Invasive Adenocarcinoma

Management of early invasive adenocarcinoma is individualised and depends on multiple factors such as the age of the patient, the tumour stage and precise measurements, parity, fertility issues and the patient’s wishes. There is good evidence that FIGO stage 1A1 adenocarcinomas can be treated by local excision (more than one local excision may be necessary to ensure the margins are clear of premalignant and malignant disease) with clear margins and follow up [18, 23–27]. Radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection is usually undertaken for FIGO 1A2 and small 1B1 adenocarcinomas, although trachelectomy is an option for such neoplasms when fertility preservation is an issue. If simple hysterectomy is being undertaken for a FIGO stage 1A1 adenocarcinoma, local excision with clear margins should be achieved before hysterectomy in order to ensure that a larger focus of invasion is not present. Studies have shown an extremely low risk of lymph node and parametrial involvement and of tumour recurrence or metastasis in cervical adenocarcinomas 2 cm or less in maximum dimension raising the possibility that such tumours could be safely treated by local excision [18, 23–27]; however, such management is not in widespread use and carefully designed studies are necessary to determine the efficacy and safety of such methods of treatment. In a literature review of 1,170 stage 1A cervical adenocarcinomas, there was no difference in survival between stage 1A1 and 1A2 neoplasms [26].

Cervical Adenocarcinoma

Gross Features of Primary Cervical Adenocarcinomas

There are no specific gross features of any of the morphological subtypes of primary cervical adenocarcinoma. A mass is usually present which may be polypoid, ulcerated or result in a “barrel-shaped” cervix. In some cases, there is little or no mucosal abnormality but diffuse thickening of the cervical wall. Cystic areas may be present, especially in adenoma malignum. Mesonephric adenocarcinomas usually arise deep within the lateral wall of the cervix from mesonephric remnants. However, at diagnosis, a location deep within the cervical wall is generally no longer apparent. Small adenocarcinomas may not be visible grossly. In larger neoplasms, there may be obvious gross invasion of the uterine corpus and/or extension outside the uterus.

Usual Type Cervical Adenocarcinoma (Mucinous Adenocarcinoma of Endocervical Type)

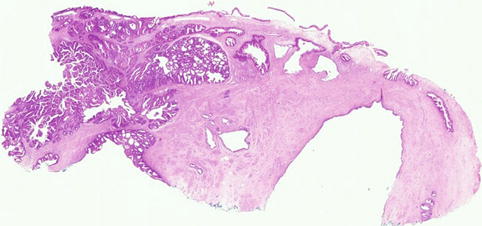

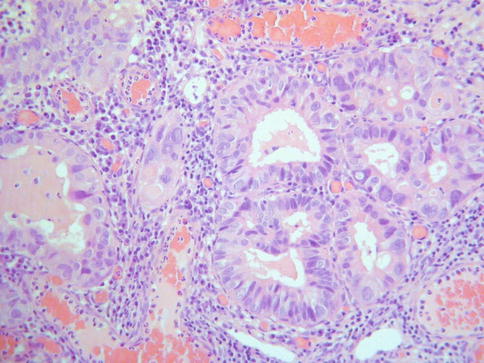

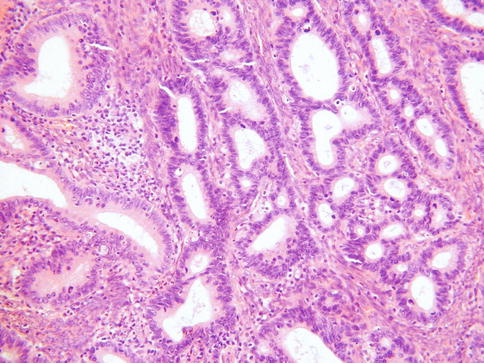

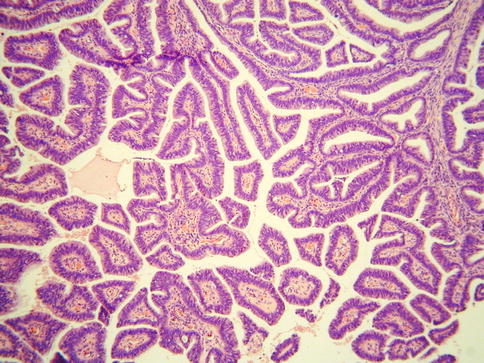

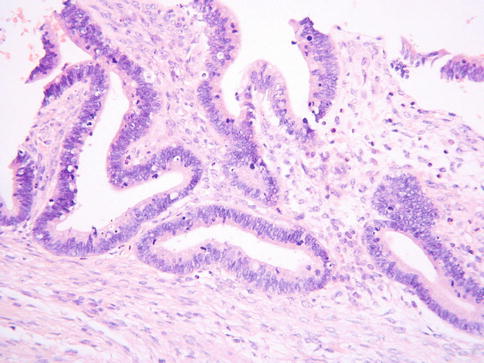

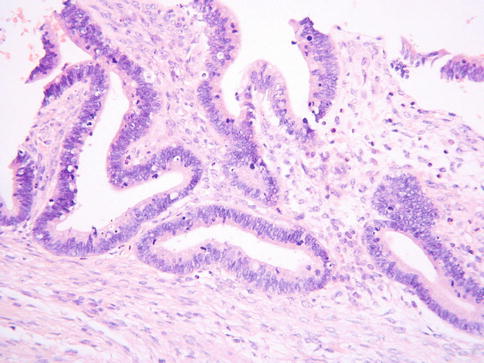

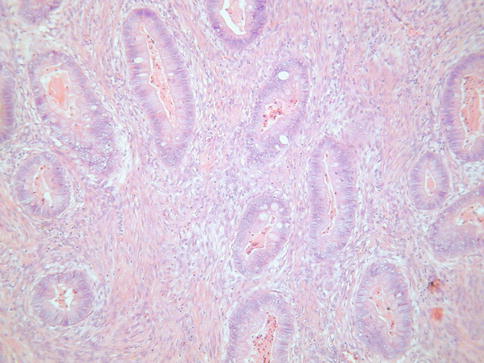

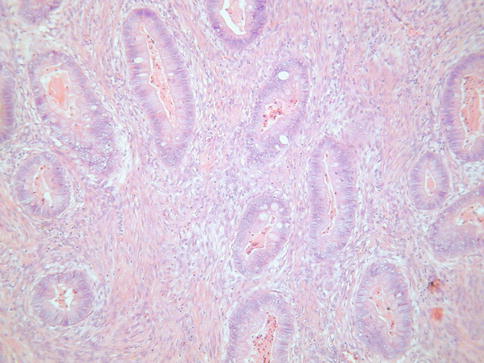

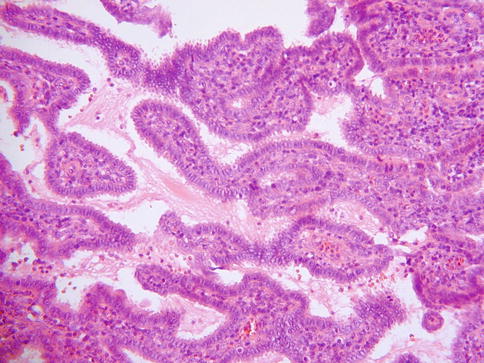

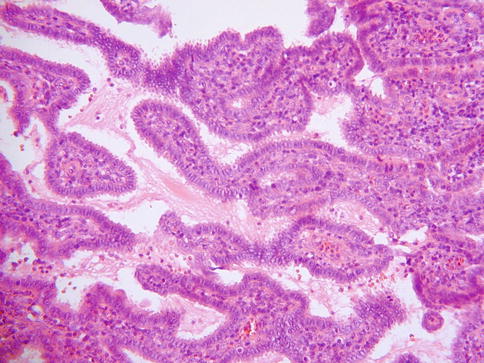

As discussed, this is the most common subtype of cervical adenocarcinoma. These neoplasms are referred to as mucinous adenocarcinoma of endocervical type by the WHO [2] but these are not overtly mucinous and others refer to these as usual type cervical adenocarcinoma which is the preferred designation [14, 15]. They are often associated with and arise from CGIN. CIN may also be present. Most of these neoplasms are HPV- associated. An association with hormonal use has also been suggested but this is not generally accepted [28]. As stated, most examples of this tumour type are not overtly mucinous and contain relatively inconspicuous intracytoplasmic mucin, although special stains may reveal sparse apical and intracytoplasmic accumulation [14, 15]. Architecturally, these neoplasms are often relatively well differentiated with glandular formation throughout much of the tumour (Fig. 4.5). Solid areas may occur but are relatively uncommon. The nuclei are hyperchromatic, sometimes with nucleoli, and there is often prominent mitotic and apoptotic activity, even when the neoplasms are architecturally well differentiated. The mitoses typically have a predominant luminal location and the apoptotic bodies are situated at the base of the cells (Fig. 4.6). The cytoplasm is usually lightly eosinophilic and ranges from scant to abundant. The glandular profiles are complex and at low power there is usually an obviously infiltrative growth pattern with angulated, branched, budded or cribriform glands, sometimes with “crab-like” profiles (Fig. 4.7). Some cases have a papillary architecture, especially towards the surface (Fig. 4.8), and should not be mistaken for other types of cervical adenocarcinoma which characteristically form papillae such as serous and villoglandular (see below). Intraluminal papillae occur in some cases. In some papillary variants of usual endocervical type adenocarcinoma, the tumour is predominantly located on the mucosal surface with an exophytic growth pattern and little in the way of stromal invasion. Such cases should not be diagnosed as CGIN but as exophytic adenocarcinomas since the architecture is too complex to conform to the normal endocervical glandular field. Even though there is no underlying stromal invasion, the tumour thickness and horizontal extent should be measured and the FIGO stage determined from these measurements. A stromal desmoplastic, inflammatory or oedematous reaction is usually present at least focally but some usual endocervical type adenocarcinomas are characterized by a so-called “naked” pattern of invasion and melt through the stroma without eliciting a reaction (Fig. 4.9). Lymphovascular and perineural invasion are often seen.

Fig. 4.5

Well differentiated cervical adenocarcinoma with good glandular differentiation

Fig. 4.6

Cervical adenocarcinoma containing luminal mitoses and basal apoptotic bodies

Fig. 4.7

Cervical adenocarcinoma with angulated and crab-like glands

Fig. 4.8

Cervical adenocarcinoma with prominent papillary architecture

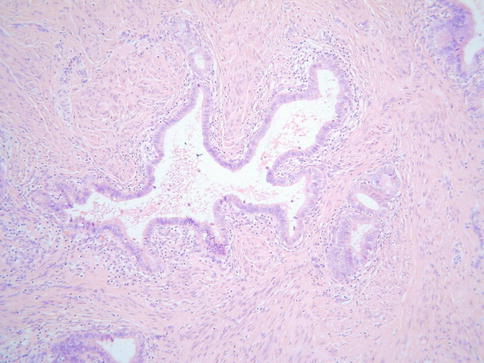

Fig. 4.9

Cervical adenocarcinoma exhibiting “naked” pattern of invasion with no stromal response

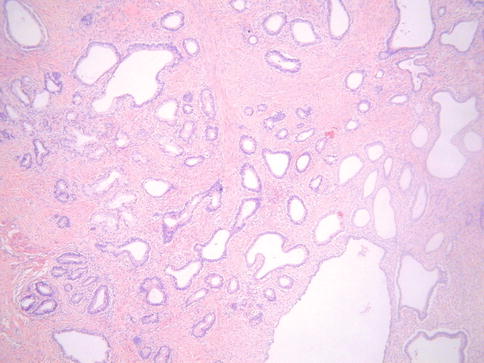

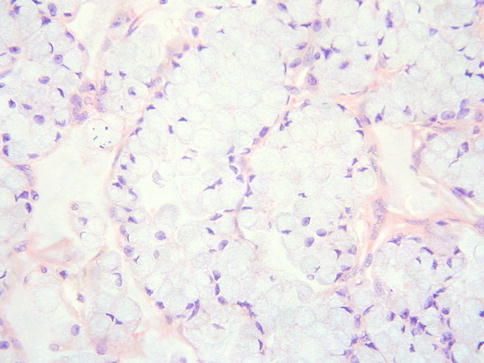

A rare microcystic variant of usual type adenocarcinoma has been described which at low power resembles dilated benign glands or tunnel clusters (Fig. 4.10) [29]. This variant of adenocarcinoma is distinguished from benign lesions by the presence, at least focally, of some combination of nuclear atypia, a stromal response, significant mitotic and apoptotic activity and cribriform foci [29]. Areas of typical adenocarcinoma may also be present. Occasional examples of usual type adenocarcinoma have a prominent microglandular architecture, sometimes with conspicuous acute inflammatory cells, and may mimic microglandular hyperplasia [30]. This phenomenon, which is more commonly seen in adenocarcinomas of the uterine corpus, is rare and is usually a focal finding. A rare variant has been described containing areas resembling breast lobular carcinoma with Indian-file, nested and targetoid growth patterns and intracytoplasmic lumina (Fig. 4.11); these neoplasms exhibit loss of E-cadherin staining which may account for the morphological appearances [31]. Choriocarcinomatous and hepatoid differentiation have rarely been reported [32, 33]. Occasional cervical neoplasms consist of an admixture of adenocarcinoma and a neuroendocrine carcinoma, either of small cell or large cell type.

Fig. 4.10

Micocystic variant of cervical adenocarcinoma

Fig. 4.11

Cervical adenocarcinoma resembling breast lobular carcinoma

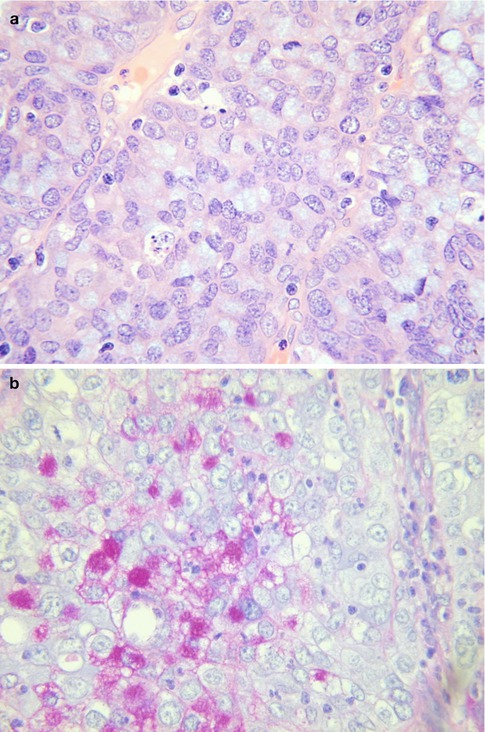

There is no universal grading system for cervical adenocarcinomas but it has been recommended that these neoplasms are graded using the FIGO system for endometrial adenocarcinomas [12]. Others use nuclear grading systems. A poorly differentiated cervical carcinoma with no evidence of squamous differentiation (intercellular bridges or keratinisation) but with conspicuous intracytoplasmic mucin, as demonstrated by mucin stains, should be categorized as a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma [2] (Fig. 4.12a, b).

Fig. 4.12

Poorly differentiated cervical adenocarcinoma with intracytoplasmic mucin (a). Mucin stain in poorly differentiated cervical adenocarcinoma (b)

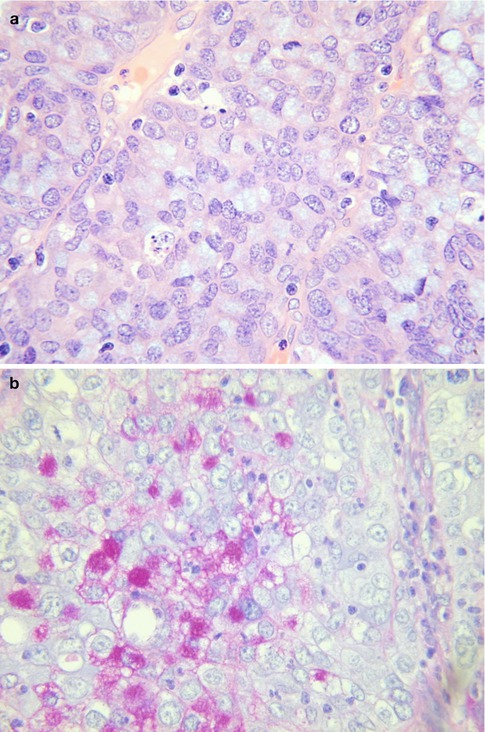

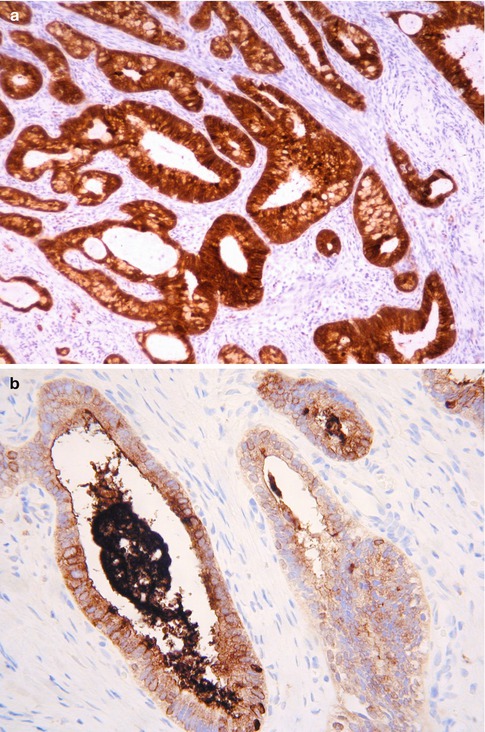

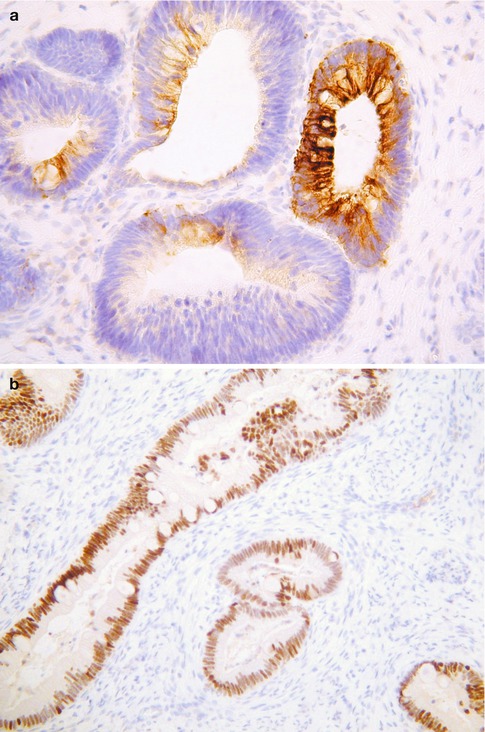

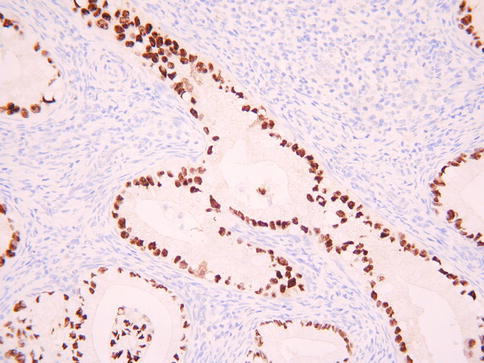

Most usual endocervical type adenocarcinomas are diffusely positive with CK7, CEA (cytoplasmic staining) and p16 (Fig. 4.13a, b). ER, PR and vimentin are usually negative or focally positive but occasional cases exhibit diffuse immunoreactivity, especially with ER; those cases which are diffusely immunoreactive with ER tend to be well differentiated but this is not invariable [34–38]. A panel of markers comprising CEA, p16, ER and vimentin, along with molecular tests for HPV, may be useful in the distinction between a usual endocervical type adenocarcinoma and a low grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus [34–38] (see section on “Distinction between endometrial and cervical adenocarcinoma”). Scattered chromogranin positive neuroendocrine cells are found in some usual endocervical type adenocarcinomas [39].

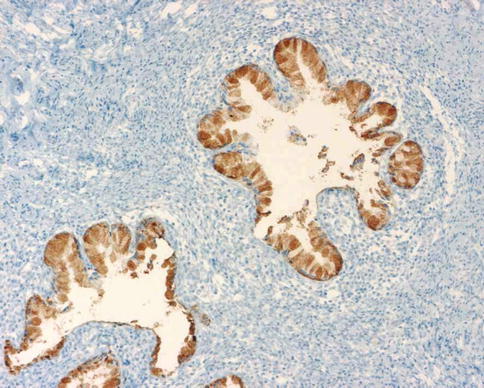

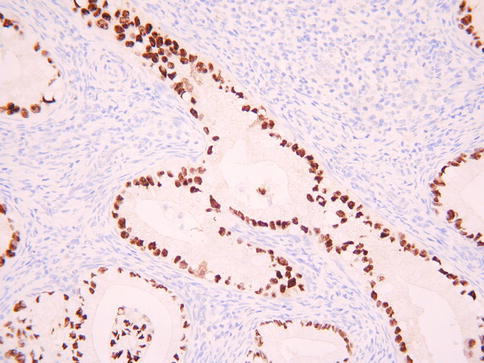

Fig. 4.13

Cervical adenocarcinoma which is diffusely positive with p16 (a) and CEA (b)

Occasional usual endocervical-type adenocarcinomas, some with limited tumour within the cervix, result in prominent endometrial or endo/myometrial involvement and may simulate a primary endometrial adenocarcinoma, even to the extent that there are foci which resemble atypical endometrial hyperplasia [40]. Such cases may be misdiagnosed as a primary endometrial adenocarcinoma with cervical extension or independent synchronous neoplasms. In such cases, molecular studies to look for HPV and immunohistochemistry may be useful in proving that this represents a primary cervical adenocarcinoma with extension to the uterine corpus (see section on “Distinction between endometrial and cervical adenocarcinoma”).

Another peculiar scenario which may result in diagnostic confusion is the ability of metastatic cervical adenocarcinomas in the ovary to mimic primary ovarian neoplasms of endometrioid or mucinous type. Some of these cases, similar to metastatic adenocarcinomas from other organs, exhibit a pronounced maturation phenomenon and contain areas mimicking borderline or even benign ovarian neoplasia (Fig. 4.14) [41, 42]. On occasions, the primary adenocarcinoma in the cervix is very small or even not recognisably invasive and the ovarian neoplasm may be discovered before there is known to be a lesion in the cervix [41, 42]. In such cases, the ovarian involvement may be secondary to transuterine and transtubal spread and the prognosis is relatively favourable compared to other stage IV cervical adenocarcinomas [41, 42]. Clues that one is dealing with a metastasis (these may not all be present) include the fact that the ovarian neoplasms are often bilateral and exhibit prominent surface involvement. There is often a “hybrid” of endometrioid and mucinous features. Extensive sampling often reveals foci more suggestive of a secondary such as destructive stromal invasion or extensive lymphovascular involvement. There may also be endometrial or endo/myometrial involvement. Molecular studies to demonstrate HPV and diffuse p16 staining may be of value in helping to confirm a cervical primary. ER staining may also assist when the differential includes a primary ovarian endometrioid neoplasm since the latter are usually diffusely positive while primary cervical adenocarcinomas are usually negative or exhibit focal immunoreactivity.

Fig. 4.14

Metastatic cervical adenocarcinoma in ovary exhibiting maturation phenomenon with areas resembling a benign or borderline mucinous neoplasm of the ovary

Management and Prognosis of Cervical Adenocarcinomas

The management of cervical adenocarcinomas is similar to corresponding stage cervical squamous carcinomas and the morphological subtype of adenocarcinoma does not play any significant role in affecting the management. Stage 1A1 adenocarcinomas can be managed by local excision (see section on “Management of early invasive adenocarcinoma”) while radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection is usually undertaken for stage 1A2 and 1B1 and sometimes stage 2A. Primary chemoradiation is usually administered for stage 1B2, 2B and above. It is controversial whether cervical adenocarcinomas have a worse prognosis stage for stage compared to squamous carcinomas and this is not proven. In a large study published in abstract form of 230 cases of cervical adenocarcinoma of all morphological subtypes, Eftekhar et al. found a 5 year survival of 76.6 % for all stages. The 5 year survival was 100, 89, 83, 49, 34 and 3.3 % for stage 1A, 1B1, 1B2, 2, 3 and 4 respectively [43]. The survival rate was 92, 73 and 66 % respectively for well, moderate and poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas. Patients with negative lymph nodes had a 5 year survival of 92 % compared to 65 % for those with positive nodes. In another study [44], the 5 year survival rates were 80.1, 59.7, 6.3 and 0.0 % respectively for patients with stage 1, 2, 3 and 4 cervical adenocarcinoma; the overall 5 year survival rate was 59.0 %. Univariate analysis indicated a poor prognosis for non-exophytic tumours, tumour diameter >4 cm, advanced clinical stage, mucinous adenocarcinoma and clear cell carcinoma and poorly differentiated tumour. The prognosis was also related to lymph node metastasis and deep myometrial invasion. Multivariate analysis indicated that in addition to clinical stage, myometrial invasion, lymph node metastasis and tumour shape were also independent prognostic factors [44]. The prognosis of the more unusual morphological subtypes of cervical adenocarcinoma, some of which probably have a worse outcome than usual endocervical type adenocarcinomas, is discussed in the appropriate sections.

Intestinal Type Mucinous Adenocarcinoma

This is an uncommon variant of primary cervical adenocarcinoma which is not well described in the literature and which morphologically resembles a colorectal adenocarcinoma. Some, but probably not all, arise from a villous adenoma. Morphologically, these neoplasms are characterized by goblet cells and “dirty” necrosis (Fig. 4.15) [45–49]. Paneth and neuroendocrine cells may be present. There is no adjacent CGIN. These neoplasms differ from those usual endocervical-type adenocarcinomas which arise from intestinal type CGIN. Only a small number of intestinal-type cervical adenocarcinomas have been studied by immunohistochemistry and most have been diffusely positive with CK7 and focally or diffusely positive with CK20 and CDX2 (Fig. 4.16a, b) [46, 48]. p16 staining has been variable [46, 48]. These tumours are probably not associated with HPV.

Fig. 4.15

Intestinal type cervical adenocarcinoma with goblet cells

Fig. 4.16

Intestinal type cervical adenocarcinoma exhibiting focal staining with CK20 (a) and diffuse staining with CDX2 (b)

Intestinal type cervical adenocarcinoma is distinguished from metastasis or direct spread from a colorectal primary by a combination of clinical and pathological parameters, including history, radiological appearances and pattern of cervical involvement. Colorectal adenocarcinomas involving the cervix are often predominantly located within the deep cervical stroma underlying normal endocervical glands. Immunohistochemistry may assist in that primary cervical intestinal-type adenocarcinoma is usually diffusely CK7 positive and only focally positive with CK20 while colorectal metastasis is usually diffusely positive with CK20 and CK7 negative, although rectal primaries may be CK7 positive [50]. Enteric type mucins (o-acetylated sialomucins) have been demonstrated in some primary cervical adenocarcinomas, including those not exhibiting any morphological evidence of intestinal differentiation [51].

Signet-Ring Cell Mucinous Adenocarcinoma

Primary cervical adenocarcinomas with a component of signet ring cells are very rare [52, 53]. The signet ring cells may be present throughout the tumour but are more commonly a focal phenomenon, usually in association with a usual endocervical-type adenocarcinoma (Fig. 4.17). If the entire neoplasm is composed of signet ring cells, a metastasis from the breast, stomach or elsewhere should be excluded. CK7, CEA and p16 are usually positive. Rare cervical squamous carcinomas may contain signet ring cells [54], as can clear cell carcinoma. Diathermy can result in signet ring-stromal cells but the nuclei are not atypical and epithelial markers are negative [55].

Fig. 4.17

Primary cervical adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells

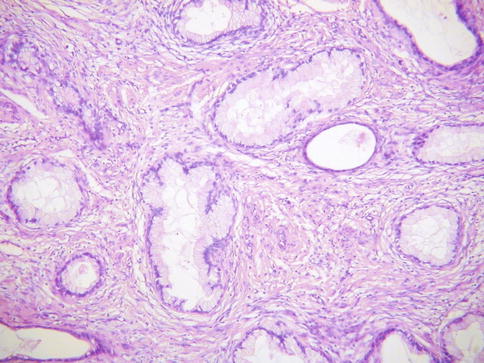

Mucinous Variant of Minimal Deviation Adenocarcinoma (Adenoma Malignum)

The mucinous variant of minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (MDA) (adenoma malignum) is a rare, but well known, type of cervical adenocarcinoma accounting for approximately 1–2 % of all primary cervical adenocarcinomas and occurring over a wide age range [56]. The term MDA was proposed by Silverberg and Hurt in 1975 [57]. There is a well known association with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, although a minority of tumours occurs in patients with this syndrome. This is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterised by intestinal hamartomatous polyps in association with mucocutaneous melanocytic macules and caused by germ-line mutation of the LKB1 (STK11) gene [58]. Abnormalities of LKB1 have been identified in some sporadic cases of cervical MDA unassociated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. For example, in one study somatic mutations involving this gene were demonstrated in 6 of 11 (55 %) cases of MDA [59]. MDAs with the mutation had a significantly poorer prognosis that those without. In another study, loss of heterozygosity of LKB1 was demonstrated in cases of MDA [60]. Cervical MDA is not related to HPV [3–5, 61, 62] and it has been suggested that these neoplasms arise in some cases from the benign endocervical glandular lesion, lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia [62–64].

In most cases, presentation is with symptoms similar to other cervical tumours, such as abnormal vaginal bleeding, but some patients present with profuse mucoid vaginal discharge. Clinically and grossly the cervix may be normal (making diagnosis difficult) or firm, enlarged and indurated. Cystic areas are present in some neoplasms. Radiological examination may reveal diffuse enlargement of the cervix with cystic areas [65].

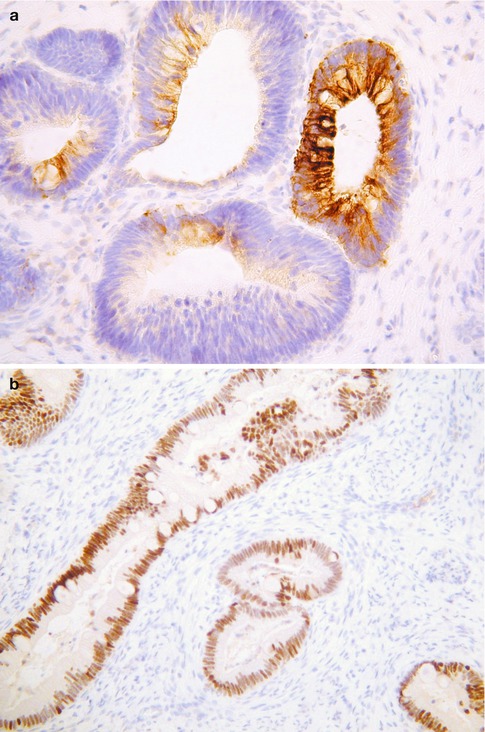

Histologically, MDA is characterized by an extremely well differentiated appearance and a haphazard arrangement of glands with irregular profiles which usually deeply infiltrate the cervical stroma (Fig. 4.18). There is an absence of the normal lobular endocervical glandular architecture, irregular spacing and claw or crab-shaped profiles. The glands are usually highly variable in size and shape; some may be cystic or exhibit papillary infolding. Most of the tumour cells contain abundant intracytoplasmic mucin with basal nuclei and exhibit minimal cytological atypia, mitotic and apoptotic activity. Stromal desmoplasia is usually present at least focally and is useful in confirming a malignant process (Fig. 4.19). Proximity of glands to thick walled stromal blood vessels may also be a useful diagnostic clue in helping to confirm a malignant process. Extensive sampling often reveals focal areas of overt nuclear atypia (Fig. 4.20). Perineural and lymphovascular space invasion also facilitate the diagnosis and help to exclude a benign lesion. In some cases, focal areas in keeping with lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia or atypical lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia are present (see Chap. 2, section on “Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia”) and it has been suggested that this represents a precursor lesion to some cases of MDA [62, 63].

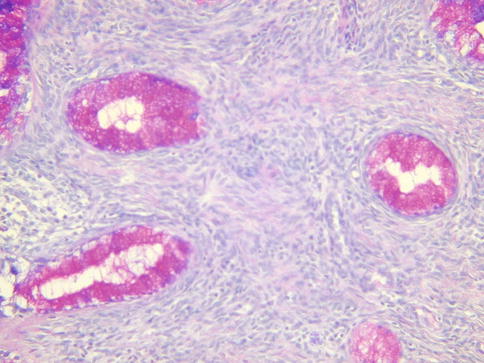

Fig. 4.18

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma of mucinous type (adenoma malignum) composed of glands lined by bland mucinous epithelium

Fig. 4.19

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma of mucinous type (adenoma malignum) consisting of bland glands with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin and surrounded by a desmoplastic stromal response

Fig. 4.20

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma of mucinous type (adenoma malignum) with focal areas exhibiting nuclear atypia

Because of the bland morphological features, there is a risk of underdiagnosis and mistaking MDA for normal endocervical glands or a benign endocervical glandular lesion, especially on a small biopsy specimen. However, there is also a risk of overdiagnosis of MDA since various benign endocervical glandular lesions, including lobular and diffuse endocervical glandular hyperplasia and others, may somewhat resemble MDA. It is helpful that most of the benign endocervical glandular lesions do not form a mass, although occasionally lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia forms a grossly visible lesion [64].

Some usual endocervical-type adenocarcinomas are well differentiated without marked nuclear atypia. These should not be misdiagnosed as MDA which is a highly differentiated adenocarcinoma characterized by the presence of cells with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin and little mitotic or apoptotic activity. It has been shown that there is significant interobserver variability amongst pathologists in the diagnosis of MDA [66].

MDA is considered to belong to a spectrum of benign, premalignant and malignant endocervical glandular lesions which exhibit gastric (pyloric) differentiation (see Table 2.1– Chap. 2) [65]. Other lesions considered to be part of this spectrum include type A tunnel clusters, simple gastric metaplasia, lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (complex gastric metaplasia) and gastric type adenocarcinoma [65, 67]. Immunohistochemically, MDA is often positive with HIK1083 and MUC6 (Fig. 4.21) [68–70], markers of pyloric gland mucins, although these markers are not, at present, in widespread use and are not totally specific for gastric type lesions. CEA is usually positive with cytoplasmic immunoreactivity, although this is not always the case and staining with this marker may be focal [34, 71]; only diffuse cytoplasmic staining is diagnostically useful in the distinction from benign endocervical glands since the latter may exhibit luminal immunoreactivity. p16 is usually negative or focally positive [3–5, 34]. ER and PR are usually negative (Fig. 4.22) and CA125 is negative or focally positive [69]. In contrast to the situation with benign endocervical glandular lesions, the desmoplastic stroma surrounding the glands of MDA is predominantly smooth muscle actin positive and ER negative [72]. A component of neuroendocrine cells is often seen in MDA when neuroendocrine markers are performed [56]. The tumour cells contain neutral mucins and stain red with combined Alcian-blue/PAS while normal endocervical glands stain a purple-violet colour due to their admixture of acid and neutral mucins (Fig. 4.23) [73]; however, in practice there is some overlap in the staining patterns.

Fig. 4.21

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma of mucinous type (adenoma malignum) which is positive with HIK1083

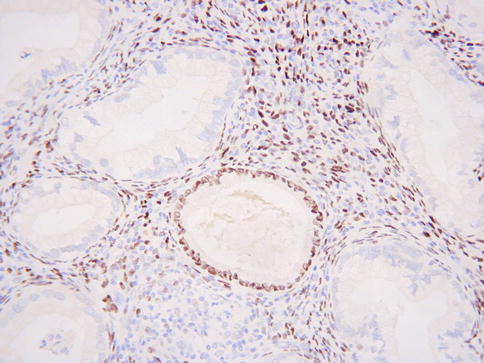

Fig. 4.22

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma of mucinous type (adenoma malignum) which is ER negative. A benign endocervical gland is positive

Fig. 4.23

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma of mucinous type (adenoma malignum) stains red with combined alcian blue/PAS

In cases of MDA with or without Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, mucinous lesions are occasionally present elsewhere in the genital tract, such as the ovary and fallopian tube; in such cases, it may be difficult to ascertain whether these represent independent synchronous lesions or bland metastasis from the cervical tumour [74, 75].

Overall, MDA has a poor prognosis, although it is not clear whether the prognosis is worse stage for stage compared to usual endocervical type adenocarcinomas. It is possible that the poor prognosis is due to a delay in diagnosis in some cases. In a literature review performed some years ago, it was found that only 30 % of patients (all stages) and 50 % of patients with stage 1 tumours were alive and disease free after 5 years [56].

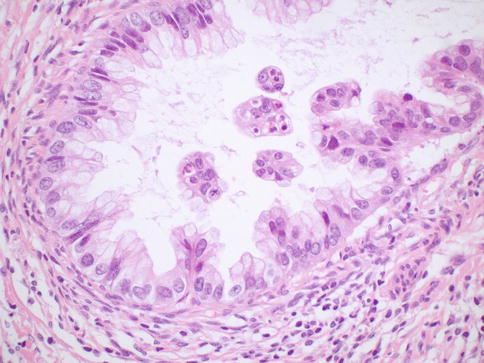

Gastric Type Cervical Adenocarcinoma

This variant of cervical adenocarcinoma has been described by Japanese investigators and is not included in the 2003 WHO classification of cervical neoplasms [76]. It is an uncommon, but not rare, type of primary cervical adenocarcinoma and, like MDA, is not HPV related and is considered to exhibit gastric differentiation [3–5, 77]. It may be more common in Japanese than Western populations. Other features in common with MDA include the fact that some cases are associated with and possibly arise from lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia and occasional occurrence in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. However, in contrast to MDA, primary gastric type adenocarcinoma is characterized by obvious malignant cytological features.

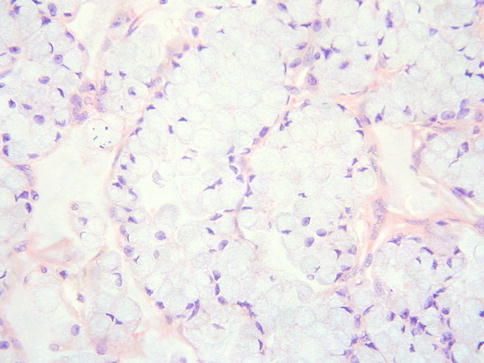

Histologically, gastric type adenocarcinoma is characterised by tumour cells with atypical nuclei and abundant clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm, typically with distinct cell borders (Fig. 4.24) [76]. There is sometimes a marked associated inflammatory infiltrate, including lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils. The tumour cells are often positive with HIK1083 and MUC6, markers of pyloric gland mucins [76]. They may be diffusely p53 (Fig. 4.25) and CEA positive and p16 is usually negative or focally positive [3–5, 76]. ER and PR are negative.

Fig. 4.24

Gastric type cervical adenocarcinoma with abundant clear cytoplasm and prominent cells membranes

Fig. 4.25

Gastric type cervical adenocarcinoma exhibiting diffuse nuclear staining with p53

Occasional neoplasms with an admixture of MDA and gastric type adenocarcinoma have been reported and it is likely that these constitute a spectrum of malignancies exhibiting gastric differentiation [78].

Although the clinical features have not been extensively studied, it is thought that gastric type adenocarcinoma is associated with aggressive behaviour and a poor prognosis, including a possible propensity for peritoneal and adnexal dissemination [76]. Kojima et al. found that gastric type adenocarcinomas had a 5 year disease free survival of 30 % compared to 74 % for usual endocervical-type adenocarcinomas [76].

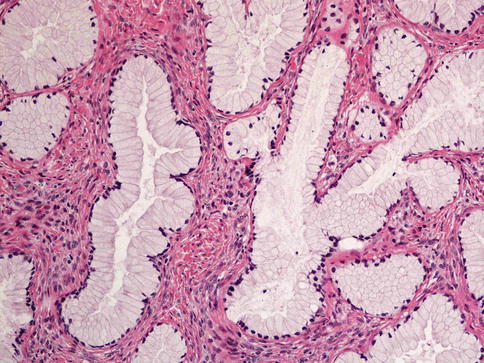

Villoglandular Adenocarcinoma

Villoglandular adenocarcinoma is a very uncommon and probably overdiagnosed variant of primary cervical adenocarcinoma which most commonly occurs in relatively young patients (average age 35) [79, 80]. It is likely that there is significant interobserver variability amongst pathologists in the diagnosis of villoglandular adenocarcinoma [81] and this diagnosis should not be made with any cervical adenocarcinoma with a papillary architecture since usual endocervical type adenocarcinomas, serous adenocarcinomas and other variants may have a focal or diffuse papillary architecture, especially towards the surface. Villoglandular adenocarcinomas are HPV related neoplasms [82] and it has been suggested that there is an association with hormonal preparations (67 % of patients in one series-79).

Grossly, villoglandular adenocarcinomas are exophytic polypoid lesions. Morphologically they are characterized by thick or thin papillae covered by columnar epithelium which generally contains little intracellular mucin (Fig. 4.26). Atypia is mild or at the most moderate. Mitoses are usually present but are not prominent. The cores of the papillae typically contain conspicuous numbers of inflammatory cells. There may be associated CGIN. Some cases are almost entirely exophytic with little or no invasion of the underlying tissues, although this is not always the case. Examples in which there is no invasion of the underlying cervical stroma may be misdiagnosed as CGIN but the overall architecture is too complex to conform to the normal endocervical glandular field. In those cases which exhibit invasion of the stroma, the “invasive” component may have a papillary architecture, comprising elongated branching glands, or resemble a usual endocervical-type adenocarcinoma. Measurement of those lesions which do not exhibit significant invasion of the stroma may be difficult but the tumour thickness should be measured as well as the lateral extent. A definitive diagnosis of villoglandular adenocarcinoma should only be made in an excision specimen since foci resembling villoglandular adenocarcinoma can be seen in other papillary adenocarcinomas.

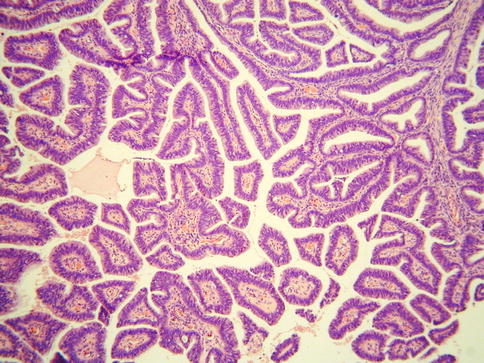

Fig. 4.26

Villoglandular cervical adenocarcinoma with pronounced papillary architecture and little in the way of nuclear atypia

In most cases, the tumour is confined to the cervix at diagnosis and villoglandular adenocarcinomas are widely assumed to have a good prognosis, although there are few large studies with long term follow up [79, 80, 83]. It has been suggested that conservative management, in the form of local excision, suffices in some patients. However, management should be individualized and those tumours which exhibit significant stromal invasion should be managed as for usual endocervical-type adenocarcinomas, especially since there are few reported case series with significant follow up. Conservative management should probably be reserved for those neoplasms which are purely villoglandular in type, confined to the surface or exhibit only superficial invasion of the stroma and in which there is no lymphovascular invasion.

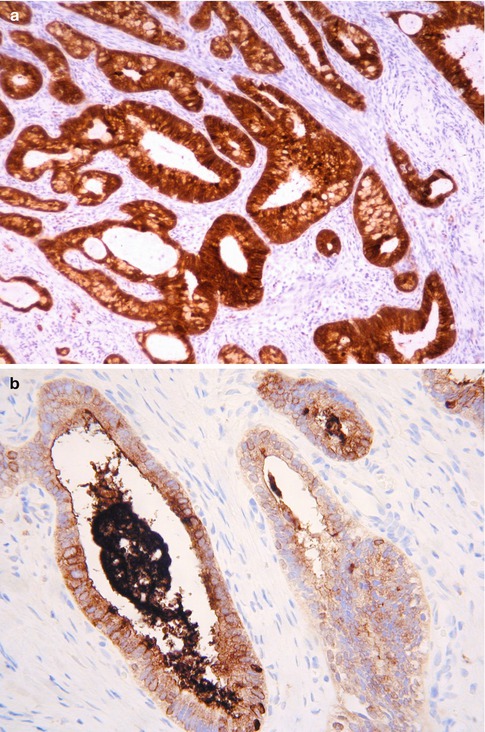

Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma

Some authorities previously considered that endometrioid adenocarcinomas of the cervix are common and account for up to 30 % of primary cervical adenocarcinomas [84, 85]. However, most cases diagnosed as primary cervical endometrioid adenocarcinomas probably represent usual endocervical type adenocarcinomas with minimal intracytoplasmic mucin, resulting in a pseudoendometrioid appearance, and true primary endometrioid adenocarcinomas of the cervix are rare. The diagnosis should probably be reserved for neoplasms which contain morphologically bland squamous elements (Fig. 4.27) [86], these being common in primary endometrioid adenocarcinomas of the uterine corpus and ovary. Primary endometrioid adenocarcinomas of the cervix are characterized by simple to complex glands lined by endometrioid type epithelium with stratified nuclei and minimal intracytoplasmic mucin and squamous elements in the form of morules or keratinizing squamous epithelium. When classical endometrioid features are present, spread from a primary neoplasm in the uterine corpus should be excluded.