The three basic cell types of carcinoma of the lung – small cell (about 15%, of all lung cancers), adenocarcinoma (40%), and squamous cell (35%) – have distinct clinical features and are associated with different paraneoplastic syndromes. Large cell carcinoma of the lung (10% to 15%) is the term reserved for those carcinomas not meeting histologic criteria of the three classic types.

Although some tumors have a mixed histologic picture, particularly squamous and adenocarcinomas, distinct clinical features are the rule. The mixed tumors may reflect stem cell malignancy with differentiation into separate cell lines.

Lung Cancer Metastases

All bronchogenic carcinomas have the potential for widespread metastases, frequently involving bone and brain, and are associated with a poor prognosis.

Lung cancer shows a peculiar predilection for metastasis to the adrenals and pituitary.

Lung cancer shows a peculiar predilection for metastasis to the adrenals and pituitary.

Metastases to pituitary and adrenals are relatively common, but clinical manifestations are rare.

The posterior pituitary is the part of the gland most commonly involved, explaining the association of lung cancer with diabetes insipidus (DI); principally small cell carcinomas, but nonsmall cell carcinomas also cause this syndrome.

The posterior pituitary is the part of the gland most commonly involved, explaining the association of lung cancer with diabetes insipidus (DI); principally small cell carcinomas, but nonsmall cell carcinomas also cause this syndrome.

Carcinoma of the breast is the other tumor associated with DI. Adrenal metastases from lung cancer, although very common, only rarely cause adrenal insufficiency.

Smoking is, of course, the major risk factor for all types of lung cancer, but a significant minority of patients with adenocarcinoma have no smoking history. Asbestos exposure is also a risk factor for all types of lung cancer and the risk is compounded by smoking. Asbestos is the major cause of mesothelioma.

Radiographically, lung cancer metastases to bone appear lytic but contain a small rim of osteoblastic activity and are therefore associated with an elevated alkaline phosphatase level (made by osteoblasts) and a positive bone scan.

Radiographically, lung cancer metastases to bone appear lytic but contain a small rim of osteoblastic activity and are therefore associated with an elevated alkaline phosphatase level (made by osteoblasts) and a positive bone scan.

Superior Vena Cava (SVC) Syndrome

Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome, obstruction of blood flow in the SVC, is an important complication of both small and nonsmall cell lung cancer.

Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome, obstruction of blood flow in the SVC, is an important complication of both small and nonsmall cell lung cancer.

Centrally located tumors, particularly those on the right side, are the usual cause. Lymphomas also may cause the SVC syndrome along with other diseases of the mediastinum including aneurysms, fibrosing disorders, and metastatic cancers.

The symptoms and signs are the predictable consequences of venous obstruction to the drainage of the head, neck, and upper thorax, including: plethora, facial edema and suffusion, increased venous pattern on the right chest, tortuous veins on funduscopic examination, and sometimes, papilledema in severe cases.

Digital Clubbing

Digital clubbing occurs in over one-half of patients with nonsmall cell carcinoma of the lung.

Digital clubbing occurs in over one-half of patients with nonsmall cell carcinoma of the lung.

Clubbing, a spongy elevation of the base of the nail that obliterates the usual angle formed by the nail with its base, is associated, additionally, with a variety of different diseases including suppurative intrathoracic processes, cyanotic congenital heart disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and biliary cirrhosis among others.

Clubbing is rare in small cell carcinoma of the lung and in uncomplicated TB.

Clubbing is rare in small cell carcinoma of the lung and in uncomplicated TB.

The most exuberant clubbing occurs in patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung.

The most exuberant clubbing occurs in patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung.

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Bronchogenic carcinomas are associated with a wide variety of paraneoplastic syndromes as noted in Table 13-1. Different cell types produce distinct syndromes with reasonable fidelity.

TABLE 13.1 Paraneoplastic Syndromes with Bronchogenic Carcinomas

Adenocarcinoma of the Lung

Adenocarcinomas of the lung tend to be peripheral in location (in contrast to the other types which tend to be central).

Adenocarcinomas of the lung tend to be peripheral in location (in contrast to the other types which tend to be central).

Bronchoalveolar carcinoma of the lung, a subtype of adenocarcinoma now referred to as carcinoma in situ because it does not invade the lung interstitium, is characterized by aerogenous spread via the bronchi; although the prognosis may be better than other types when localized, it may be associated with widespread disease throughout the lung fields, and a correspondingly poor prognosis.

Adenocarcinomas may develop in relation to parenchymal scars within the lungs – the so called “scar carcinoma.”

Adenocarcinomas may develop in relation to parenchymal scars within the lungs – the so called “scar carcinoma.”

These may occur in the area of old tuberculous scars.

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy, the subperiosteal deposition of new bone, occurs in association with exuberant clubbing, and is most common in association with adenocarcinoma of the lung.

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy, the subperiosteal deposition of new bone, occurs in association with exuberant clubbing, and is most common in association with adenocarcinoma of the lung.

A common clinical presentation is ankle pain and swelling although the wrists may occasionally be involved as well. Bone scan is diagnostic, showing subperiosteal enhancement in the long bones of the extremities.

It may be associated with a velvety thickening and pigmentation over the skin of the palms. The pathogenesis is not well understood but growth factors produced by the tumor are suspected to contribute.

Trousseau’s syndrome, migratory superficial thrombophlebitis, is associated with adenocarcinoma of the lung.

Trousseau’s syndrome, migratory superficial thrombophlebitis, is associated with adenocarcinoma of the lung.

Described by Armand Trousseau in the mid-19th century, and now recognized to be a manifestation of malignancy associated hypercoagulable state, thrombophlebitis may complicate adenocarcinoma of the lung. As a paraneoplastic syndrome the thrombophlebitis may antedate the clinical presentation of the tumor. Mucinous adenocarcinomas of the lung, the stomach, or the pancreas are the usual causes of this syndrome. Ironically, a few years after describing this entity Trousseau diagnosed it in himself and subsequently went on to die from pancreatic (some say gastric) carcinoma.

Arterial thromboses have been noted as well although some of those described may have been paradoxical emboli through a patent foramen ovale.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Lung

Originating centrally more commonly than in the periphery, squamous cell lung cancers frequently cavitate and may cause confusion with lung abscess.

Originating centrally more commonly than in the periphery, squamous cell lung cancers frequently cavitate and may cause confusion with lung abscess.

As compared with lung abscesses the walls of a cavitated squamous carcinoma appear thicker and have a shaggy appearance.

In an edentulous patient a cavitary lesion on chest x-ray is a carcinoma until proved otherwise.

In an edentulous patient a cavitary lesion on chest x-ray is a carcinoma until proved otherwise.

Lung abscesses usually occur in conjunction with poor oral hygiene and periods of diminished consciousness.

Squamous carcinomas originating in the apex of the lung (the “superior sulcus” or Pancoast tumor) are associated with a characteristic constellation of symptoms and signs known as Pancoast’s syndrome.

Squamous carcinomas originating in the apex of the lung (the “superior sulcus” or Pancoast tumor) are associated with a characteristic constellation of symptoms and signs known as Pancoast’s syndrome.

The clinical manifestations result from local invasion of surrounding tissues including the brachial plexus, the superior cervical (sympathetic) ganglion, ribs and vertebral bodies.

Gnawing pain in the neck, shoulder, and upper back, worse at night, may become unbearable; weakness and atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand and Horner’s syndrome reflect invasion of the ipsilateral nerve roots and the sympathetic paravertebral chain.

Gnawing pain in the neck, shoulder, and upper back, worse at night, may become unbearable; weakness and atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand and Horner’s syndrome reflect invasion of the ipsilateral nerve roots and the sympathetic paravertebral chain.

Disruption of the cervical components of the SNS causes miosis, ptosis, and anhydrosis – Horner’s syndrome.

Squamous cell cancer of the lung may be associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome known as humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy (HHM), caused by production and secretion of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) by the tumor.

Squamous cell cancer of the lung may be associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome known as humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy (HHM), caused by production and secretion of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) by the tumor.

Hypercalcemia in association with malignancy has several causes: bony dissolution secondary to extensive osteolytic metastatic disease; cytokine activation of osteoclast activity; the production of calcitriol; and the production of PTHrP which results in the HHM syndrome. PTHrP, a homolog of parathyroid hormone (PTH) that reproduces some of the biologic actions of PTH, is the most common cause of hypercalcemia in solid tumors (absent known bone metastases) and is the usual cause of hypercalcemia in patients with squamous cell carcinomas.

Small Cell Carcinoma of the Lung

A highly aggressive malignancy derived from pulmonary neuroendocrine cells, small cell carcinoma of the lung is usually widespread at the time of initial diagnosis.

A highly aggressive malignancy derived from pulmonary neuroendocrine cells, small cell carcinoma of the lung is usually widespread at the time of initial diagnosis.

Small cell carcinoma of the lung, previously known as oat cell carcinoma, is the malignant counterpart of the differentiated carcinoid tumor. It is extremely rare in those who have never smoked. Typically forming large central masses, small cell lung cancer is a common cause of SVC syndrome.

A number of distinct paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with small cell carcinoma of the lung, reflecting, perhaps, the neuroendocrine origin of this tumor.

A number of distinct paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with small cell carcinoma of the lung, reflecting, perhaps, the neuroendocrine origin of this tumor.

Syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion (SIADH), ectopic ACTH syndrome, Lambert–Eaton syndrome, and cerebellar degeneration are all well recognized entities complicating small cell lung cancer. Treatments that destroy the tumor reverse the paraneoplastic syndromes.

SIADH may be caused by any intrathoracic process that stimulates, inappropriately, the release of ADH from the posterior pituitary. Some tumors, however, produce and secrete ADH directly, as is the case with small cell carcinoma of the lung.

SIADH may be caused by any intrathoracic process that stimulates, inappropriately, the release of ADH from the posterior pituitary. Some tumors, however, produce and secrete ADH directly, as is the case with small cell carcinoma of the lung.

In the presence of hyponatremia and low serum osmolality, a urine osmolality greater than plasma or less than maximally dilute is diagnostic of SIADH. The urinary sodium is generally high reflecting dietary intake.

The ectopic ACTH syndrome secondary to small cell carcinoma of the lung differs from other causes of Cushing’s syndrome in several ways: weight loss rather than weight gain modifies the usual physical stigmata that depend on fat accumulation such as moon facies and buffalo hump; hypokalemic alkalosis, rare in other forms of Cushing’s syndrome, dominates the clinical course; and hyperpigmentation, due to very high ACTH levels, is usually present. Diabetes, hypertension, and muscle weakness are also prominent features.

The ectopic ACTH syndrome secondary to small cell carcinoma of the lung differs from other causes of Cushing’s syndrome in several ways: weight loss rather than weight gain modifies the usual physical stigmata that depend on fat accumulation such as moon facies and buffalo hump; hypokalemic alkalosis, rare in other forms of Cushing’s syndrome, dominates the clinical course; and hyperpigmentation, due to very high ACTH levels, is usually present. Diabetes, hypertension, and muscle weakness are also prominent features.

The ACTH levels in the ectopic ACTH syndrome associated with small cell carcinomas of the lung are very high resulting in the production of a variety of mineralocorticoids (such as deoxycorticosterone) which cause the hypertension and the hypokalemic alkalosis. Aldosterone is not increased.

The Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) superficially resembles myasthenia gravis (MG) but is distinct on both clinical and pathophysiologic grounds. In the majority of cases LEMS is a paraneoplastic syndrome most commonly associated with small cell carcinoma of the lung; it also can occur without detectable cancer although vigilance is required since LEMS may antedate the appearance of cancer by years.

The Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) superficially resembles myasthenia gravis (MG) but is distinct on both clinical and pathophysiologic grounds. In the majority of cases LEMS is a paraneoplastic syndrome most commonly associated with small cell carcinoma of the lung; it also can occur without detectable cancer although vigilance is required since LEMS may antedate the appearance of cancer by years.

MG is an autoimmune disease caused by antibodies directed at the skeletal muscle cholinergic receptor; as a consequence the receptor is degraded and the muscle response diminishes with repeated nerve stimulation. LEMS is also associated with an autoantibody but with a different target: the voltage-gated calcium channel on the prejunctional neuronal membrane. This antibody blocks the calcium channel and antagonizes the release of acetylcholine from the presynaptic neuron.

The clinical features of LEMS in comparison with MG include greater lower extremity involvement, less ocular and bulbar involvement, enhanced muscle contraction with repeated stimulation rather than fatigue of the response.

The clinical features of LEMS in comparison with MG include greater lower extremity involvement, less ocular and bulbar involvement, enhanced muscle contraction with repeated stimulation rather than fatigue of the response.

Antibodies to the voltage-gated calcium channel can be demonstrated in most patients with LEMS and are useful diagnostically similar to the percentage of patients with generalized MG that have cholinergic receptor autoantibodies; by contrast, only about 50% of patients with ocular MG have demonstrable antibodies to the cholinergic receptor.

Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration occurs most commonly with small cell carcinoma of the lung.

Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration occurs most commonly with small cell carcinoma of the lung.

The tumor is associated with autoantibodies directed against the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. Lymphoma and breast cancer have also been associated with cerebellar degeneration.

Imaging studies are not helpful in diagnosing cerebellar degeneration except for ruling out other diseases affecting the cerebellum.

Imaging studies are not helpful in diagnosing cerebellar degeneration except for ruling out other diseases affecting the cerebellum.

The clinical features of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration are typical of those found in cerebellar dysfunction of other causes: nausea, vomiting, dizziness, ataxia, inability to walk or stand, and diplopia among others.

The clinical features of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration are typical of those found in cerebellar dysfunction of other causes: nausea, vomiting, dizziness, ataxia, inability to walk or stand, and diplopia among others.

The Lambert–Eaton syndrome and other forms of paraneoplastic degeneration may sometimes accompany the cerebellar degeneration.

RENAL CELL CARCINOMA

Renal cell carcinoma (hypernephroma) is commonly associated with systemic manifestations, some of which reflect the biologic effects of cytokines released from the tumor, others as manifestations of classic paraneoplastic syndromes.

Renal cell carcinoma (hypernephroma) is commonly associated with systemic manifestations, some of which reflect the biologic effects of cytokines released from the tumor, others as manifestations of classic paraneoplastic syndromes.

At the present time only a small minority of patients demonstrate the classic triad of hematuria, flank pain, and an abdominal mass at presentation. Systemic symptoms often dominate the clinical picture and the diagnosis is frequently made by imaging techniques which demonstrate a renal mass.

Fever, night sweats, and cachexia are common manifestations of renal cell carcinoma that reflect cytokine release. Anemia and thrombocytosis are common as well secondary to the chronic inflammatory state.

Fever, night sweats, and cachexia are common manifestations of renal cell carcinoma that reflect cytokine release. Anemia and thrombocytosis are common as well secondary to the chronic inflammatory state.

Local spread into the vena cava and adjacent lymph nodes, and metastases to lung, bone, liver, and brain are common complications. The inflammatory state may also result in secondary (AA) amyloidosis.

The paraneoplastic complications of renal cell carcinoma include hypercalcemia, erythrocytosis, and hypertension.

The paraneoplastic complications of renal cell carcinoma include hypercalcemia, erythrocytosis, and hypertension.

Hypercalcemia reflects both bony metastases and the secretion of PTHrP by the tumor.

Hypercalcemia reflects both bony metastases and the secretion of PTHrP by the tumor.

The metastases appear lytic on bone films but, like lung tumor metastases, an osteoblastic rim elevates the alkaline phosphatase and results in a positive radionuclide bone scan.

Erythropoietin production by the tumor is relatively common but erythrocytosis is only noted in a small minority of patients, a consequence, perhaps, of cytokine suppression of erythropoiesis.

Erythropoietin production by the tumor is relatively common but erythrocytosis is only noted in a small minority of patients, a consequence, perhaps, of cytokine suppression of erythropoiesis.

Hypertension also complicates renal cell carcinoma, likely a consequence of renin production by tumor cells or by compressed adjacent kidney parenchyma.

Hypertension also complicates renal cell carcinoma, likely a consequence of renin production by tumor cells or by compressed adjacent kidney parenchyma.

MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Myeloma, a plasma cell malignancy, classically presents with bone pain and anemia. Lytic lesions in bone, a normal alkaline phosphatase, and an “M” spike on serum protein electrophoresis is virtually diagnostic of multiple myeloma, but the diagnosis is usually confirmed by bone marrow aspirate showing an excess of (immature) plasma cells and by measurement and quantification of immunoglobulin levels.

Myeloma, a plasma cell malignancy, classically presents with bone pain and anemia. Lytic lesions in bone, a normal alkaline phosphatase, and an “M” spike on serum protein electrophoresis is virtually diagnostic of multiple myeloma, but the diagnosis is usually confirmed by bone marrow aspirate showing an excess of (immature) plasma cells and by measurement and quantification of immunoglobulin levels.

Clonal expansion of plasma cells in the bone marrow, paraprotein spike in excess of 3 g, and increases in circulating and urinary light chains make the diagnosis.

The bone lesions in myeloma are purely lytic, so alkaline phosphatase is not elevated and bone scans are unrevealing.

The bone lesions in myeloma are purely lytic, so alkaline phosphatase is not elevated and bone scans are unrevealing.

The lytic lesions are caused by the production of osteoclast-activating factors, a variety of cytokines that stimulate osteoclasts and inhibit osteoblasts.

Pathologic fractures are an important complication of myeloma; they may involve vertebrae and/or long bones.

Persistent low back pain, often mistaken for degenerative lumbosacral spine disease, is a frequent presentation, especially in the elderly.

Persistent low back pain, often mistaken for degenerative lumbosacral spine disease, is a frequent presentation, especially in the elderly.

The coincidental finding of anemia (normochromic, normocytic) in a patient with unrelenting low back pain indicates the need for further workup.

The lumbar spine is most commonly involved in compression fractures due to myeloma, although any area of the spine may be affected. Osteoporotic fractures, in contrast, most commonly involve the thoracic spine.

The lumbar spine is most commonly involved in compression fractures due to myeloma, although any area of the spine may be affected. Osteoporotic fractures, in contrast, most commonly involve the thoracic spine.

Hypercalcemia occurs in a significant proportion of cases due to bony dissolution in conjunction with immobilization due to pain.

Hypercalcemia occurs in a significant proportion of cases due to bony dissolution in conjunction with immobilization due to pain.

Glucocorticoids are an important component of the treatment of the hypercalcemia.

Renal Involvement in Myeloma

Renal insufficiency in myeloma is common and involves several distinct pathogenetic mechanisms: light chain cast nephropathy (“myeloma kidney”) is the most common.

Renal insufficiency in myeloma is common and involves several distinct pathogenetic mechanisms: light chain cast nephropathy (“myeloma kidney”) is the most common.

Myeloma kidney is due to intratubular obstruction by filtered light chains that precipitate in the renal tubules and damage the tubular epithelium.

Bence Jones proteinuria, now of historical interest, was a test for myeloma that depended on the precipitation of the urinary light chains when the urine was heated followed by solubilization of the protein precipitate as the heating was continued. Direct determination of clonal light chains in plasma and urine has replaced the test for Bence Jones proteins.

Radiologic contrast media may precipitate light chains in the urine and result in acute renal failure; x-ray contrast media should be avoided in all patients with suspected myeloma.

Radiologic contrast media may precipitate light chains in the urine and result in acute renal failure; x-ray contrast media should be avoided in all patients with suspected myeloma.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be avoided as well.

Additional causes of azotemia in patients with myeloma include amyloidosis (AL), hypercalcemia, and mesangial deposition of light chains.

Additional causes of azotemia in patients with myeloma include amyloidosis (AL), hypercalcemia, and mesangial deposition of light chains.

Severe renal involvement is a poor prognostic sign in patients with myeloma.

Impaired Antibody Production in Myeloma

All patients with myeloma have deficient antibody production, an acquired form of hypogammaglobulinemia despite elevated globulin levels. As such they are subject to severe and sometimes recurrent infections, most often with encapsulated organisms.

All patients with myeloma have deficient antibody production, an acquired form of hypogammaglobulinemia despite elevated globulin levels. As such they are subject to severe and sometimes recurrent infections, most often with encapsulated organisms.

Since antibody-mediated opsonization is critical to host defenses against encapsulated organisms all patients with functional hypogammaglobulinemia are at risk for infections with pneumococci and Klebsiella, staphylococci, and Escherichia coli. The usual sites of infection are the lungs (pneumonia) and the kidneys (pyelonephritis).

Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are at similar risk since they are functionally hypogammaglobulinemic as well.

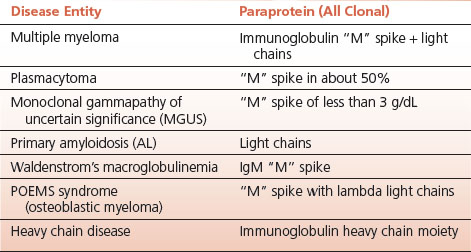

TABLE 13.2 Plasma Cell Dyscrasias and Related Paraproteins

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree