Major Depressive Disorder

KEY CONCEPTS

![]() Extensive treatment guidelines are available to assist in the treatment of major depressive disorder, including medication management. Clinicians treating individuals with major depressive disorder should be familiar with these guidelines.

Extensive treatment guidelines are available to assist in the treatment of major depressive disorder, including medication management. Clinicians treating individuals with major depressive disorder should be familiar with these guidelines.

![]() When evaluating a patient for the presence of depression, it is essential to rule out medical causes of depression and drug-induced depression.

When evaluating a patient for the presence of depression, it is essential to rule out medical causes of depression and drug-induced depression.

![]() The goal of pharmacologic treatment of depression is the resolution of current symptoms (i.e., remission) and the prevention of further episodes of depression (i.e., relapse or recurrence).

The goal of pharmacologic treatment of depression is the resolution of current symptoms (i.e., remission) and the prevention of further episodes of depression (i.e., relapse or recurrence).

![]() When counseling patients with depression who are receiving antidepressant medications, the patient should be informed that adverse effects might occur immediately, while resolution of symptoms may take 2 to 4 weeks or longer. Adherence to the treatment plan is essential to a successful outcome, and tools to help increase medication adherence should be discussed with each patient.

When counseling patients with depression who are receiving antidepressant medications, the patient should be informed that adverse effects might occur immediately, while resolution of symptoms may take 2 to 4 weeks or longer. Adherence to the treatment plan is essential to a successful outcome, and tools to help increase medication adherence should be discussed with each patient.

![]() Antidepressants are generally considered equally efficacious in groups of patients with major depressive disorder. Therefore, other factors, such as age, side effect profile, and past history of response, are used to guide the selection of antidepressants.

Antidepressants are generally considered equally efficacious in groups of patients with major depressive disorder. Therefore, other factors, such as age, side effect profile, and past history of response, are used to guide the selection of antidepressants.

![]() When determining if a patient has been nonresponsive to a particular pharmacotherapeutic intervention, it must be determined whether the patient has received an adequate dose for an adequate duration and whether the patient has been medication adherent.

When determining if a patient has been nonresponsive to a particular pharmacotherapeutic intervention, it must be determined whether the patient has received an adequate dose for an adequate duration and whether the patient has been medication adherent.

![]() Pharmacogenetic tests (e.g., the FDA-approved AmpliChip to evaluate CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms) are now commercially available. However, there are no standard or well-accepted recommendations for the use of pharmacogenetic testing as it relates to antidepressant treatment of major depressive disorder.

Pharmacogenetic tests (e.g., the FDA-approved AmpliChip to evaluate CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms) are now commercially available. However, there are no standard or well-accepted recommendations for the use of pharmacogenetic testing as it relates to antidepressant treatment of major depressive disorder.

![]() When evaluating response to an antidepressant, in addition to target signs and symptoms, the clinician must consider quality-of-life issues, such as role, social, and occupational functioning. In addition, the tolerability of the agent should be assessed because the occurrence of side effects may lead to medication nonadherence, especially given the chronicity of the disease and need for long-term medication management.

When evaluating response to an antidepressant, in addition to target signs and symptoms, the clinician must consider quality-of-life issues, such as role, social, and occupational functioning. In addition, the tolerability of the agent should be assessed because the occurrence of side effects may lead to medication nonadherence, especially given the chronicity of the disease and need for long-term medication management.

A diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) is given when an individual experiences one or more major depressive episodes without a history of manic, mixed, or hypomanic episodes. A major depressive episode is defined by the criteria listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).1 Depression is associated with significant functional disability, morbidity, and mortality. Newer generations of antidepressants, such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are effective and better tolerated than older agents, such as the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). In addition, substantial efforts have been undertaken to improve the ability of clinicians to recognize and appropriately treat the signs and symptoms of depression. This chapter focuses exclusively on the diagnosis and treatment of MDD.

![]() In the absence of well-accepted evidence-based medicine for the medication management of MDD, the reader is referred to the Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder, which is available at www.psych.org. This extensive document (now available in its third iteration) is a practical guide to the management of depression based on the best available data as well as clinical consensus.2

In the absence of well-accepted evidence-based medicine for the medication management of MDD, the reader is referred to the Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder, which is available at www.psych.org. This extensive document (now available in its third iteration) is a practical guide to the management of depression based on the best available data as well as clinical consensus.2

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The true prevalence of depressive disorders in the United States is unknown. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication found that 16.2% of the population studied had a history of MDD in their lifetime, and more than 6.6% had an episode within the past 12 months.3 Women have a higher risk of depression than men from early adolescence until their mid-50s, with a lifetime rate that is 1.7 to 2.7 times greater.4 Although depression can occur at any age, adults 18 to 29 years of age experience the highest rates of major depression during any given year.3 The estimated lifetime prevalence of major depression in individuals aged 65 to 80 recently was reported to be 20.4% in women and 9.6% in men.5 Depressive disorders are common during adolescence, with comorbid substance abuse, suicide attempts, and deaths occurring frequently in these young patients.6,7 Depressive disorders and suicide tend to occur within families. For example, approximately 8% to 18% of patients with major depression have at least one first-degree relative (father, mother, brother, or sister) with a history of depression, compared with 5.6% of the first-degree relatives of those without depression.8 Furthermore, first-degree relatives of patients with depression are 1.5 to 3 times more likely to develop depression than normal controls.1,8,9 A recent meta-analysis found that the heritability of liability for major depression was 37%, whereas the remaining 63% of the variance in liability was due to individual-specific environment.10 Therefore, MDD is relatively common, occurs more frequently in women than in men, and prevalence is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors.

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of depressive disorders is too complex to be totally explained by a single social, developmental, or biologic theory. Several factors appear to work together to cause or precipitate depressive disorders. The symptoms reported by patients with MDD consistently reflect changes in brain monoamine neurotransmitters (NTs), specifically norepinephrine (NE), serotonin (5-HT), and dopamine (DA).11–13 See Figure 51-1 for a visual explanation of how these monoamine NTs are regulated at the level of the neuron and within the synapse.

FIGURE 51-1 Monoamine neurotransmitter (NT) regulation at the neuronal level. NTs carry messages between cells. Each NT generally binds to a specific receptor, and this coupling initiates a cascade of events. NTs are reabsorbed back into nerve cells by reuptake pumps (i.e., transporter molecules) at which point they may be recycled for later use or broken down by enzymes. For their primary mechanism of action, most antidepressants are thought to inhibit the transporter molecules and allow more NT to remain in the synapse. (Data from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Office of Science Policy and Communications, Science Policy Branch; figure reproduced from the Mind Over Matter educational series.)

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Several years before the introduction of antidepressants, the cause of depression was linked to decreased brain levels of the NTs NE, 5-HT, and DA, although the actual cause remains unknown. This biogenic amine hypothesis evolved as a result of several observations made in the early 1950s. It was noted that the antihypertensive drug reserpine depleted neuronal storage granules of NE, 5-HT, and DA and produced clinically significant depression in 15% or more of patients.14

Although the reuptake blockade of monoamines (e.g., NE, DA, and 5-HT) occurs immediately on administration of an antidepressant, the clinical antidepressant effects (i.e., measurable improvement) are generally delayed by weeks.11,15 This delay may be the result of a cascade of events from receptor occupancy to gene transcription.16 This delay in onset of action has caused researchers to focus on the adaptive changes induced by antidepressants.12 Accordingly, theories that focus on adaptive (or chronic) changes in amine receptor systems have emerged. In the mid-1970s, it was recognized that chronic, but not acute, administration of antidepressants to animals caused desensitization of NE-stimulated cyclic adenosine monophosphate synthesis. In fact, for most antidepressants, downregulation of β-adrenergic receptors accompanies this desensitization.17 Studies of many antidepressants have demonstrated that either desensitization or downregulation of NE receptors corresponds to a clinically relevant time course for antidepressant effects.11 Other studies have revealed desensitization of presynaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors following chronic administration of antidepressants.18 Thus, a theory based on changes in receptor sensitivity provides a cogent explanation of the delayed onset of therapeutic response of antidepressant drugs.11 The dysregulation hypothesis incorporates the diversity of antidepressant activity with the adaptive changes occurring in receptor sensitization over several weeks. In this theory, emphasis is placed on a failure of homeostatic regulation of NT systems rather than on absolute increases or decreases in their activities. According to this hypothesis, effective antidepressant agents restore efficient regulation to the dysregulated NT system.19

It is apparent that no single NT theory of depression is adequate. The 5-HT/NE link hypothesis maintains that both the serotonergic and noradrenergic systems are involved in an antidepressant response.17 This hypothesis is also consistent with the rationale of the postsynaptic alteration theory of depression, which emphasizes the importance of β-adrenergic receptor downregulation for achieving an antidepressant effect.17 Furthermore, both serotonergic and noradrenergic medications downregulate β-adrenergic receptors, and there is a link between 5-HT and NE.17 This implies that medications that are effective in the treatment of depression act at both of these NT systems.

Traditional explanations of the biologic basis of depressive disorders have focused largely on NE and 5-HT; however, most of the evidence that coalesced into the biogenic amine hypothesis of depression does not clearly distinguish between NE and DA. There is an abundance of evidence suggesting that DA transmission is decreased in depression and that agents that increase dopaminergic transmission have been found to be effective antidepressants.20 Specifically, studies suggest that increased DA transmission in the mesolimbic pathway accounts for at least part of the mechanism of action of antidepressant medications.20 The mechanisms by which antidepressant drugs alter DA transmission remain unclear, but may be mediated indirectly by primary actions at NE or 5-HT terminals. The complexity of the interaction between 5-HT, NE, and possibly DA is gaining greater appreciation, but a more in-depth understanding of the precise mechanism is needed.

More recent insight into the possible mechanisms underlying depressive disorders comes from studies on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF is a growth factor protein that regulates the differentiation and survival of neurons. A growing body of evidence suggests this process might be disrupted in depressive disorders. More specifically, chronic stress and an associated increase in glucocorticoids such as cortisol may cause a disruption of BDNF expression in the hippocampus. This process may be prevented, or possibly even reversed, by antidepressant medications.21 This is a relatively recent theory, which has not been firmly established. However, if proven valid, it demonstrates that antidepressants may help prevent deleterious effects of chronic stress and depressive symptoms.

Biologic Markers

Investigators continue to search for biologic or pharmacodynamic (PD) markers to assist in the diagnosis and treatment of depressed patients. Although no biologic marker has been discovered, several biologic abnormalities are present in many depressed patients. Approximately 45% to 60% of patients with major depression have a neuroendocrine abnormality, including hypersecretion of cortisol or a lack of cortisol suppression after dexamethasone administration (i.e., a positive dexamethasone suppression test). In fact, it has been suggested that the inability of the brain to suppress the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the associated stress response could lead to the pathophysiology and symptoms of depression.22 According to this theory, there is a disruption somewhere in the normal negative feedback system that controls cortisol levels (see Fig. 59-3 for a visual display of this negative feedback system). There are many potential negative consequences of excess circulating cortisol, including disruption in BDNF expression as discussed above.

Unfortunately, the high rate of false-positive and false-negative results associated with neuroendocrine abnormalities in depressed patients limits the usefulness of testing for these markers, and has led to their relative lack of use in clinical practice. However, they still provide a clue as to the potential pathophysiology of depressive disorders, which may lead us to more effective treatment options.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

![]() When a patient presents with depressive symptoms, it is necessary to investigate the possibility of a contributing medical or drug-induced etiology. All depressed patients should have a complete physical examination, mental status examination, and basic laboratory workup, including a complete blood count with differential, thyroid function tests, and electrolyte determinations, to identify any potential medical problems. A listing of all possible medical conditions associated with depression is beyond the scope of this chapter. The DSM-IV-TR describes a diagnostic category for both “Mood Disorder due to a General Medical Condition” and “Substance-Induced Mood Disorder,”1 which are common causative factors for depressive symptoms. For example, up to 40% of patients with certain neurologic disorders (e.g., stroke, Alzheimer’s disease) develop depressive symptoms at some point during the course of their illness.1 Furthermore, individuals experiencing withdrawal from substances of abuse (e.g., cocaine) commonly present with depressive symptoms.23

When a patient presents with depressive symptoms, it is necessary to investigate the possibility of a contributing medical or drug-induced etiology. All depressed patients should have a complete physical examination, mental status examination, and basic laboratory workup, including a complete blood count with differential, thyroid function tests, and electrolyte determinations, to identify any potential medical problems. A listing of all possible medical conditions associated with depression is beyond the scope of this chapter. The DSM-IV-TR describes a diagnostic category for both “Mood Disorder due to a General Medical Condition” and “Substance-Induced Mood Disorder,”1 which are common causative factors for depressive symptoms. For example, up to 40% of patients with certain neurologic disorders (e.g., stroke, Alzheimer’s disease) develop depressive symptoms at some point during the course of their illness.1 Furthermore, individuals experiencing withdrawal from substances of abuse (e.g., cocaine) commonly present with depressive symptoms.23

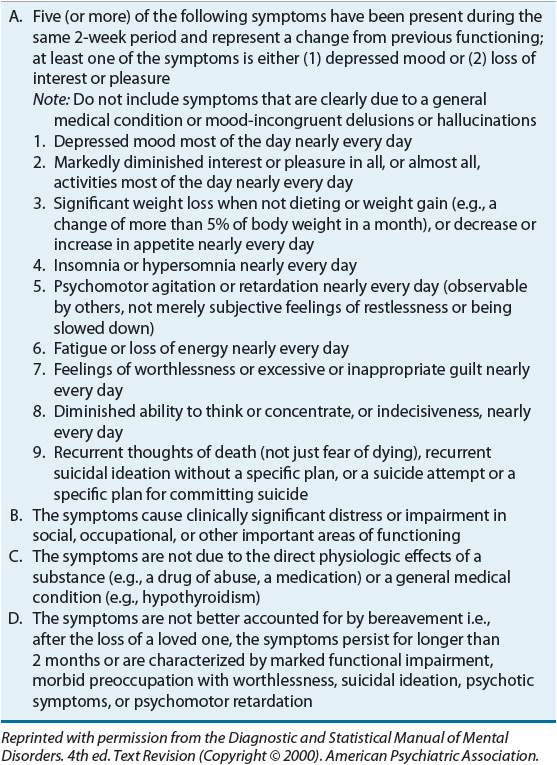

Table 51-1 lists medications commonly associated with causing or exacerbating depressive symptoms.2,24,25 A complete medication review should be performed because several medications (in addition to those listed in Table 51-1) may contribute to depressive symptoms. Once a medical condition or concomitant medication has been ruled out as the cause of the depressive symptoms, the patient should be evaluated for MDD. According to the DSM-IV-TR, a single major depressive episode is characterized by five or more of the symptoms described in Table 51-2. At least one of the symptoms is depressed mood (often an irritable mood in children or adolescents) or loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities.1 These symptoms must have been present nearly every day for at least 2 weeks and must represent a change from the patient’s previous level of functioning. The 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual omits the bereavement exclusion that appears as item D in Table 51-2. Some feel that this omission opens the door to misdiagnosis of normal grief as major depressive disorder. The diagnostic code for major depressive disorder is determined by whether this is a single or recurrent depressive episode, current severity, presence of psychotic features, and remission status. The diagnosis can be followed by specifiers that apply to the current episode. The possible specifiers include anxious distress, mixed features (i.e., presence of some manic/hypomanic features), melancholic features, atypical features, mood-congruent psychotic features, catatonia, peripartum onset, and seasonal pattern. The clinician must consider presenting symptoms, their duration, and the patient’s current level of social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Significant stressors or life events may trigger depression in some individuals but not others, and there may be an important precipitant at the beginning of the disorder.1 A patient diagnosed with MDD may have one or more recurrent episodes of major depression during his or her lifetime.

TABLE 51-1 Selected Medications Associated with Drug-Induced Depressive Symptoms

TABLE 51-2 DSM-IV-TR Criteria for Major Depressive Episode

Depression Rating Scales

Instruments to assess the severity of depressive symptoms can be used for both clinical and research purposes. For example, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) is a clinician-administered scale that is commonly used in drug trials given its sensitivity to change.26 Other depression rating scales are self-administered. For example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) takes only 5 to 10 minutes to complete by the respondent.27 For a more detailed explanation for both of these instruments, as well as other rating scales and evaluation approaches, please refer to eChapter 19.

Emotional Symptoms

A major depressive episode is characterized by a persistent, diminished ability to experience pleasure. A loss of interest and pleasure in usual activities, hobbies, or work is common. Patients appear sad or depressed, and they are often pessimistic and believe that nothing will help them feel better. The presence of feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt may identify patients at risk for suicide.28 Anxiety symptoms are present in almost 90% of depressed outpatients. Patients often have guilt feelings that are unrealistic, and these may reach delusional proportions. Patients may feel that they deserve punishment and may view their present illness as a punishment. A patient suffering from major depression with psychotic features may hear voices (auditory hallucinations) saying that he or she is a bad person and that he or she should commit suicide. Depression with psychotic features may require hospitalization, especially if the patient becomes a danger to self or others.

Physical Symptoms

Physical symptoms often motivate patients, especially the elderly, to seek medical attention. Chronic fatigue is a common complaint, with a decreased ability to perform normal daily tasks. Fatigue often appears worse in the morning and does not improve with rest. Complaints of pain, especially headache, often accompany fatigue.

Sleep disturbances generally present as frequent early morning awakening with difficulty returning to sleep. This may coexist with difficulty falling asleep and frequent nighttime awakening. Less frequently, depressed patients complain of increased sleep (hypersomnia), although they experience daytime exhaustion or fatigue.

Appetite disturbances, including complaints of decreased appetite, often result in substantial weight loss, especially in the elderly.29 Some patients lose 2 lb (0.9 kg) or more per week without dieting. Other patients, especially in the ambulatory setting, may overeat and gain weight, although they actually may not enjoy eating. Some patients exhibit GI complaints, others cardiovascular complaints, especially palpitations. Patients frequently present with a loss of sexual interest or libido.30

Intellectual or Cognitive Symptoms

Intellectual or cognitive symptoms include a decreased ability to concentrate, slowed thinking, and a poor memory for recent events. Patients may appear confused and indecisive. Depression should be considered when cognitive symptoms are present in the elderly.29

Psychomotor Disturbances

Patients may appear noticeably slowed or retarded in physical movements, thought processes, and speech (psychomotor retardation). Conversely, depression may be accompanied by psychomotor agitation, manifesting as purposeless, restless motion (e.g., pacing, wringing of hands, or outbursts of shouting).

SUICIDE RISK EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists suicide as the 11th leading cause of death among Americans and the 2nd leading cause of death among 25- to 34-year-olds. In 2006, there were 91 suicides per day in the United States.31 All patients diagnosed with MDD should be assessed for suicidal thoughts. Factors associated with an increased risk for suicide include psychiatric and substance use disorders, adolescence and younger age adults, physical illness, recent stressful life event, childhood trauma, hopelessness, and male gender.32 Those with a higher level of risk have high degrees of suicidal intent and describe more specific plans, in particular, plans that are violent and irreversible.32 It is important to remember that the risk of suicide in those recovering from major depression may increase as they develop the energy and capacity to act on a plan made earlier in a course of illness. Additionally, despite factors to help identify those at greatest risk, it remains very difficult to predict suicidality in any given individual. Therefore, when suicidal intent is suspected, it is important to ask, “Are you thinking about harming or killing yourself?” If the risk is significant, the patient must be referred immediately to an appropriate healthcare professional. Additionally, certain depression rating scales, such as the MADRS discussed above, include questions that target suicidality, which may help identify those patients at risk.

In September 2004, the FDA required manufacturers of antidepressants to add a boxed warning stating that antidepressants increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in short-term studies in children and adolescents with depressive disorders. These risks have become a new source of concern among those treating their patients with antidepressants. In order to help deal with the confusion these risks have caused, experts have recommended the following33:

1. It is especially important to closely monitor patients for suicidal ideation and behavior at the beginning of treatment and among younger patients.

2. Discuss the possibility that adverse events may occur, including behavioral agitation or anger, and encourage patients to seek help should this occur.

3. Deal with the subject of suicide directly.

It is important to note that there is little evidence to suggest that withholding antidepressant treatment decreases the risk of eventual suicide and may actually increase the risk. Furthermore, it may be that longer-term medication is needed for any protective effects against suicidality.33

In May 2007, the FDA released additional requests to the makers of antidepressants that the black box warning regarding suicidality be expanded to include warnings about the increased risk of suicidality (thinking and behavior) in young adults 18 to 24 years of age, during the initial stages of treatment.

In contrast to some of the concerns discussed above, recent evidence suggests that fluoxetine and venlafaxine may be associated with a “protective” effect from suicidality among adults and older patients; however, among youth, the medications lacked this apparent protective effect. It should be noted that Gibbons et al. did not find that fluoxetine and venlafaxine increased the risk of suicidality among youth.34 The complex relationships between antidepressant use and suicidality will continue to be explored with the hopes of more unequivocal recommendations.

TREATMENT

Desired Outcomes

The goals of treatment are to reduce the symptoms of acute depression, facilitate the patient’s return to a level of functioning like that before the onset of illness, and prevent further episodes of depression. Whether or not to hospitalize the patient is often the first decision that is made in consideration of the patient’s risk of suicide, physical state of health, social support system, and presence of a psychotic depression.

General Approach to Treatment

![]() There are three phases of treatment for patients with MDD: (a) the acute phase lasting approximately 6 to 12 weeks in which the goal is remission (i.e., absence of symptoms); (b) the continuation phase lasting 4 to 9 months after remission is achieved, in which the goal is to eliminate residual symptoms or prevent relapse (i.e., return of symptoms within 6 months of remission); and (c) the maintenance phase lasting at least 12 to 36 months in which the goal is to prevent recurrence (i.e., a separate episode of depression).2,35 The risk of recurrence increases as the number of past episodes increases. The duration of antidepressant therapy depends on the risk of recurrence. Some investigators recommend lifelong maintenance therapy for persons at greatest risk for recurrence (persons younger than 40 years of age with two or more prior episodes and persons of any age with three or more prior episodes).2

There are three phases of treatment for patients with MDD: (a) the acute phase lasting approximately 6 to 12 weeks in which the goal is remission (i.e., absence of symptoms); (b) the continuation phase lasting 4 to 9 months after remission is achieved, in which the goal is to eliminate residual symptoms or prevent relapse (i.e., return of symptoms within 6 months of remission); and (c) the maintenance phase lasting at least 12 to 36 months in which the goal is to prevent recurrence (i.e., a separate episode of depression).2,35 The risk of recurrence increases as the number of past episodes increases. The duration of antidepressant therapy depends on the risk of recurrence. Some investigators recommend lifelong maintenance therapy for persons at greatest risk for recurrence (persons younger than 40 years of age with two or more prior episodes and persons of any age with three or more prior episodes).2

![]() Educating the patient and their support system (e.g., family and friends) regarding the delay in antidepressant effects and the importance of adherence should occur before and during the entire course of treatment. The treatment of MDD generally includes non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic strategies, which are discussed in further detail below.

Educating the patient and their support system (e.g., family and friends) regarding the delay in antidepressant effects and the importance of adherence should occur before and during the entire course of treatment. The treatment of MDD generally includes non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic strategies, which are discussed in further detail below.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

In addition to pharmacologic interventions, psychotherapy should be employed whenever the patient is able and willing to participate. Psychotherapy alone is not recommended for the acute treatment of patients with severe and/or psychotic MDD. However, if the depressive episode is mild to moderate in severity, psychotherapy may be the first-line therapy.36 The effects of psychotherapy and antidepressant medications are considered to be additive. Combined treatment may be advantageous for patients with partial responses to either treatment alone and for those with a chronic course of illness. However, for uncomplicated, nonchronic MDD, combined treatment may provide no unique advantage.36 Although not extensively evaluated, cognitive therapy, behavioral therapy, and interpersonal psychotherapy appear equally effective.36 Maintenance psychotherapy as the sole treatment to prevent recurrence generally is not recommended. Often, medication alone may prevent a depressive recurrence during the maintenance phase.36

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a safe and effective treatment for certain severe mental illnesses, including MDD. Patients with depression are candidates for ECT when a rapid response is needed, risks of other treatments outweigh potential benefits, there is a history of poor response to antidepressants and a history of good response to ECT, and the patient expresses a preference for ECT.37 Guidelines developed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) include indications and contraindications for the appropriate use of ECT, procedures for obtaining informed consent, and issues in administering ECT.37 A more recent nonpharmacologic approach is repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which has demonstrated efficacy in treating MDD and does not require anesthesia as does ECT.38

Pharmacologic Therapy

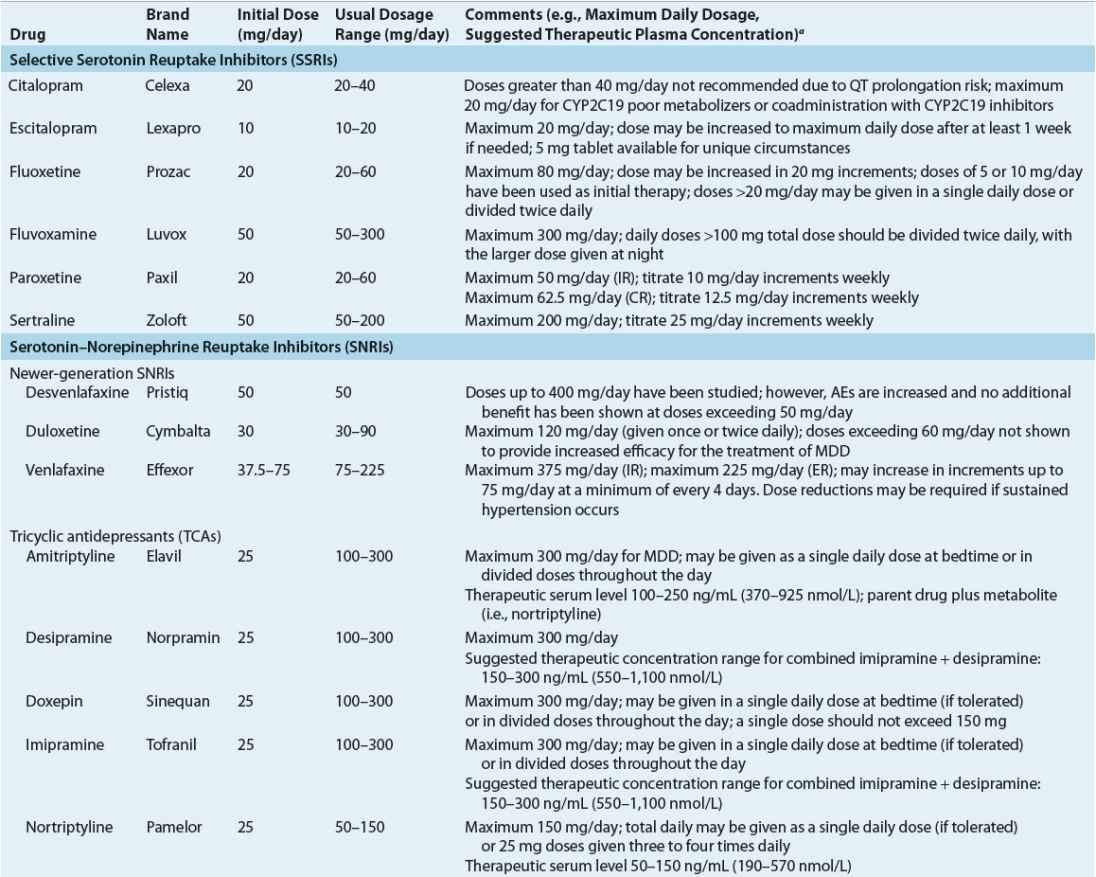

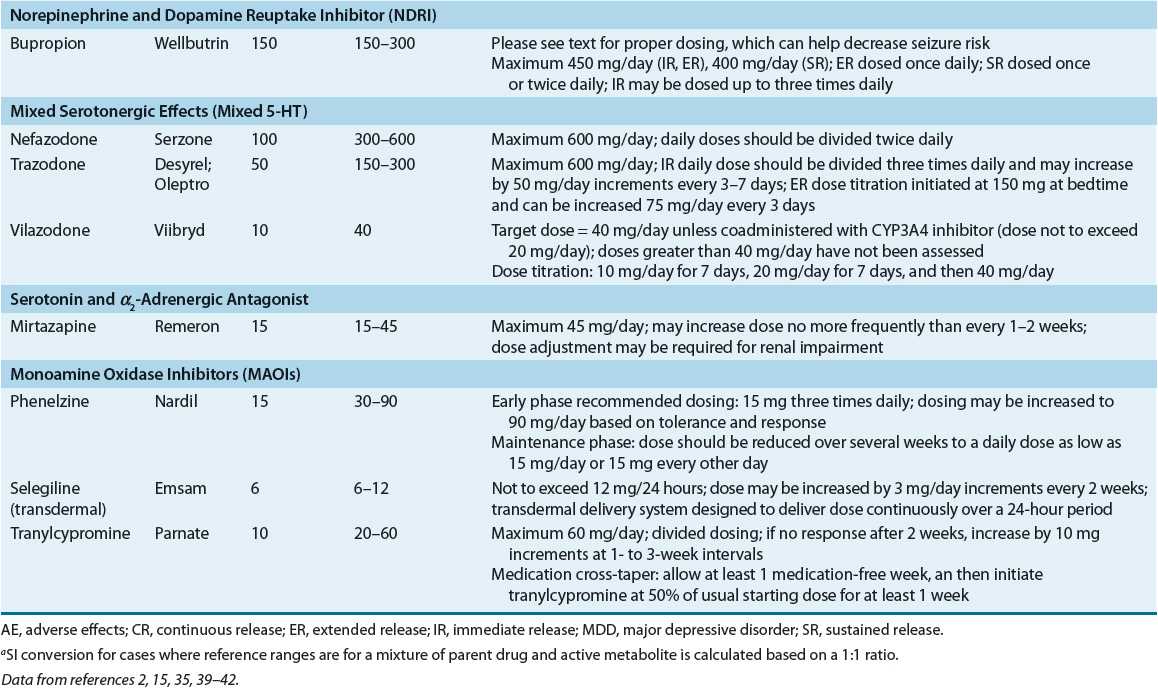

Antidepressants can be classified in several ways, including by chemical structure and the presumed mechanism of antidepressant activity. Although the link between the presumed mechanism of drug action and antidepressant response is tenuous, this classification has the advantage of being based on established pharmacology and clearly explains some of the common, but expected, adverse effects. The knowledgeable clinician can use these facts to tailor treatment to individual patient needs and thereby optimize treatment outcome. Currently available antidepressants, including dosing guidance, are provided in Table 51-3.2,15,35,39–42

TABLE 51-3 Adult Dosing Guidance for Currently Available Antidepressant Medications

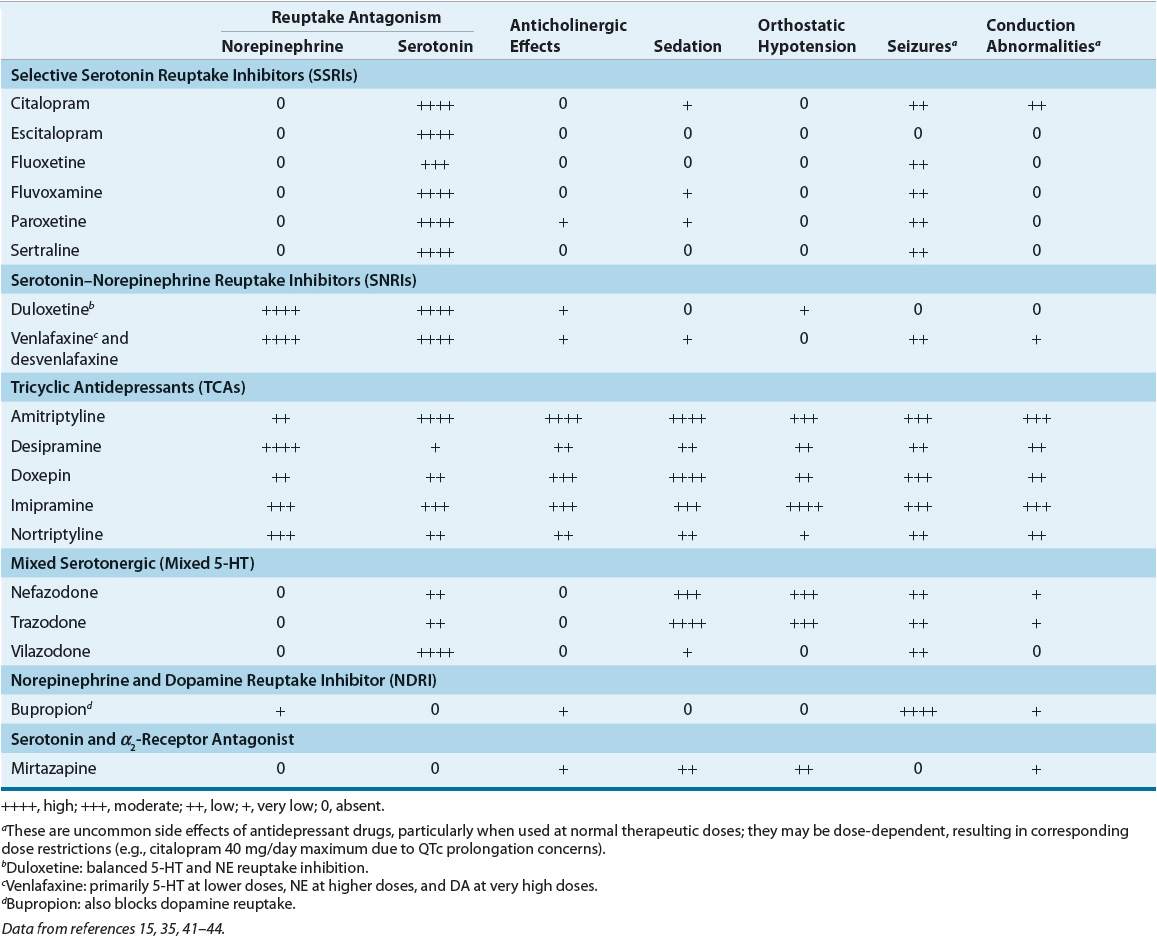

![]() Studies have found that antidepressants are of equivalent efficacy in groups of patients when administered in comparable doses. Because one cannot predict which antidepressant will be the most effective in an individual patient, the initial choice is made empirically. Factors that often influence the choice of an antidepressant include the patient’s history of response, history of familial antidepressant response, patient’s concurrent medical illnesses and medications, presenting symptoms (e.g., fatigue as compared with psychomotor agitation), potential for drug–drug interactions, adverse events profile, patient preference, and drug cost. Although the pathophysiology of major depression remains elusive, the clinician can now select from multiple approved drug therapies with presumed different mechanisms of action2 as highlighted in Table 51-4.15,35,41–44 Failure to respond to one antidepressant class or one antidepressant drug within a class does not predict a failed response to another drug class or another drug within the same class. Approximately 65% to 70% of patients with varying types of depression improve with drug therapy, compared with 30% to 40% who improve with placebo.

Studies have found that antidepressants are of equivalent efficacy in groups of patients when administered in comparable doses. Because one cannot predict which antidepressant will be the most effective in an individual patient, the initial choice is made empirically. Factors that often influence the choice of an antidepressant include the patient’s history of response, history of familial antidepressant response, patient’s concurrent medical illnesses and medications, presenting symptoms (e.g., fatigue as compared with psychomotor agitation), potential for drug–drug interactions, adverse events profile, patient preference, and drug cost. Although the pathophysiology of major depression remains elusive, the clinician can now select from multiple approved drug therapies with presumed different mechanisms of action2 as highlighted in Table 51-4.15,35,41–44 Failure to respond to one antidepressant class or one antidepressant drug within a class does not predict a failed response to another drug class or another drug within the same class. Approximately 65% to 70% of patients with varying types of depression improve with drug therapy, compared with 30% to 40% who improve with placebo.

TABLE 51-4 Relative Potencies of Norepinephrine and Serotonin Reuptake Blockade and Selected Side Effect Profile of Antidepressants

Antidepressant Medication Classes

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

The efficacy of SSRIs is superior to placebo and comparable to other classes of antidepressants in treating patients with major depression.2,35 SSRIs are generally chosen as first-line antidepressants due to their safety in overdose and improved tolerability. Furthermore, the decision as to which SSRI to use within the class is typically based on the nuances of each medication, such as differences in drug interaction profile and pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters (e.g., half-life), or due to cost considerations. These concepts will be discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs)

Tricyclic Antidepressants Although TCAs are effective in treating all depressive subtypes, their use has diminished greatly due to the availability of equally effective therapies that are much safer in overdose and better tolerated. All TCAs potentiate the activity of NE and 5-HT by blocking their reuptake. However, the potency and selectivity of TCAs for the inhibition of reuptake of NE and 5-HT vary greatly among these agents (Table 51-4). Because TCAs affect other receptor systems including the cholinergic, neurologic, and cardiovascular systems, adverse events are reported frequently during TCA therapy.15

Newer-Generation SNRIs Venlafaxine inhibits 5-HT reuptake at low doses, and NE reuptake at higher doses; thus, it is referred to as an SNRI. Desvenlafaxine, the primary active metabolite of venlafaxine, is also an SNRI and has been approved to treat depressive disorders. Duloxetine is an SNRI with both 5-HT and NE reuptake inhibition across all doses. Some studies suggest that the SNRIs may be associated with higher rates of response and remission than other antidepressants; however, most of these studies involved venlafaxine, and not all studies support this conclusion.43 A recent report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) found that discontinuation rates secondary to lack of efficacy are 34% lower (odds ratio = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.47 to 0.93) for venlafaxine compared with those for SSRIs.45

Mixed Serotonergic Medications (Mixed 5-HT)

Trazodone and nefazodone have dual actions on serotonergic neurons, acting as both 5-HT2 antagonists and 5-HT reuptake inhibitors. They may also enhance 5-HT1A-mediated neurotransmission.15 Trazodone blocks α1-adrenergic and histaminergic receptors leading to increased side effects (e.g., dizziness and sedation) that limit its use as an antidepressant. Recently, a longer-acting extended-release preparation of trazodone was approved by the FDA. However, its place in the treatment of MDD is yet to be determined. Nefazodone’s use as an antidepressant has declined as well after reports of hepatic toxicity began to emerge. The FDA-approved nefazodone labeling includes a black box warning describing rare cases of liver failure.46 Trazodone and nefazodone are effective agents in treating major depression; however, both of them carry risks that limit their usefulness as antidepressants.

Recently, vilazodone became the first combination SSRI and 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist to be approved for the treatment of MDD based on two 8-week, placebo-controlled MDD trials.47 Vilazodone’s place in therapy has yet to be determined.

Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor (NDRI)

Bupropion has no appreciable effect on the reuptake of 5-HT, but it inhibits both the NE and DA reuptake pumps.18,44 These pharmacologic properties make bupropion unique among all currently available antidepressants.

Serotonin and α2-Adrenergic Receptor Antagonists

Mirtazapine enhances central noradrenergic and serotonergic activity through the antagonism of central presynaptic α2-adrenergic autoreceptors and heteroreceptors.48 Furthermore, it antagonizes 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors as well as histamine receptors. The antagonism of 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors has been linked to lower anxiety and GI side effects, respectively. Blockade of histamine receptors is associated with the sedative properties of mirtazapine.18

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors

MAOIs increase the concentrations of NE, 5-HT, and DA within the neuronal synapse through inhibition of the MAO enzyme. Similar to TCAs, chronic therapy causes changes in receptor sensitivity (i.e., downregulation of β-adrenergic, α-adrenergic, and serotonergic receptors).49 The MAOIs phenelzine and tranylcypromine are nonselective inhibitors of MAO-A and MAO-B. A selegiline transdermal patch was approved by the FDA for treatment of MDD that allows inhibition of MAO-A and MAO-B in the brain, yet has reduced effects on MAO-A in the gut39 (see tyramine interactions with MAOIs below).