M

Masklike facies

A total loss of facial expression, masklike facies results from bradykinesia usually due to extrapyramidal damage. The rate of eye blinking is reduced to 1 to 4 blinks per minute, producing a characteristic “reptilian” stare. Although a neurologic disorder is the most common cause, masklike facies can also result from certain systemic diseases and the effects of drugs and toxins. The sign commonly develops insidiously, at first mistaken by the observer for depression or apathy.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Ask the patient and his family or friends when they first noticed the masklike facial expression and any other signs or symptoms. Find out what medications the patient is taking, if any, and ask about any changes in dosage or schedule. Determine the degree of facial muscle weakness by asking the patient to smile and to wrinkle his forehead. Typically, the patient’s responses are slowed.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Dermatomyositis. Masklike facies reflects muscle soreness, weakness, and destruction extending from the face and neck to the shoulder and pelvic girdle. Dysphagia and dysphonia develop. Characteristic cutaneous signs involve edema and dusky lilac suffusion of the eyelid margin or periorbital tissue; an erythematous rash on the face, neck, upper back, chest, arms, and nail beds; and violet (Gottron’s) papules dorsal to the interphalangeal joint.

♦ Facial palsy. Masklike facies is a hallmark of bilateral Bell’s palsy and is characterized by periaural pain, hyperacusis, and disturbance of taste.

♦ Guillain-Barré syndrome. Bilateral facial weakness may occur in this disorder and is accompanied by hypoactive reflexes, paresthesia in the extremities, and limb weakness. Respiratory insufficiency may also occur, which requires pulmonary function testing and respiratory support.

♦ Myasthenia gravis. Ptosis and generalized facial muscle weakness are common in this disorder and may be accompanied by diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, and limb weakness. Weakness typically worsens with repetitive use of muscles, and also later in the day. Pulmonary function tests may be needed to rule out impending respiratory crisis.

♦ Parkinson’s disease. Masklike facies occurs early but is commonly overlooked. This mask includes raised eyebrows and smooth facial muscles. More noticeable signs include muscle rigidity, which may be uniform (lead-pipe rigidity) or jerky (cogwheel rigidity), and an insidious tremor, which usually begins in the fingers (pillroll tremor), increases during stress or anxiety, and decreases during purposeful movement or sleep. Typically, the patient exhibits stooped posture and propulsive gait, speaks in a monotone, and may develop drooling, dysphagia, and dysarthria.

♦ Scleroderma. A late sign, masklike facies develops along with a smooth, wrinkle-free appearance, “pinching” of the mouth and, possibly, contractures as facial skin becomes tight and inelastic. Other late features include pain, stiffness, and swelling of joints and foreshortened fingers. Skin on the fingers and then on the hands and forearms thickens and becomes taut and shiny. GI dysfunction produces frequent reflux and heartburn; weight loss; diarrhea or constipation; and malodorous floating stools.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Carbon monoxide poisoning. Masklike facies usually develops several weeks after acute poisoning. The patient may also have rigidity, dementia, impaired sensory function, choreoathetosis, generalized seizures, and myoclonus.

♦ Drugs. Phenothiazines (particularly piperazine derivatives) and other antipsychotic drugs commonly cause masklike facies as well as other extrapyramidal effects. In addition, metoclopramide and metyrosine can sometimes cause masklike facies. This sign usually improves when the drug dosage is reduced or the drug therapy discontinued.

♦ Manganese poisoning (chronic). Masklike facies develops gradually, along with a resting tremor and personality changes. The patient may also experience Huntington’s disease, propulsive gait, dystonia, and rigidity. Later, extreme muscle weakness and fatigue occur.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

If the patient’s facial weakness results from Guillain-Barré syndrome or myasthenia gravis, be prepared to initiate emergency respiratory support.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Masklike facies occurs in the juvenile form of Parkinson’s disease.

PATIENT COUNSELING

If the patient’s masklike facies results from Parkinson’s disease, explain to his family that the sign may hide facial clues to depression—a common symptom of Parkinson’s disease.

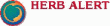

McBurney’s sign

A telltale indicator of localized peritoneal inflammation in acute appendicitis, McBurney’s sign is tenderness elicited by palpating the right lower quadrant over McBurney’s point. McBurney’s point is about 2″ (5 cm) above the anterior superior spine of the ilium, on the line between the spine and the umbilicus where pressure produces pain and tenderness in acute appendicitis. Before McBurney’s sign is elicited, the abdomen is inspected for distention, auscultated for hypoactive or absent bowel sounds, and tested for tympany.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Ask the patient to describe the abdominal pain. When did it begin? Does coughing, movement, eating, or elimination worsen or help relieve it? Also ask about the development of any other signs and symptoms such as vomiting and a low grade fever. Ask the patient to point with a finger to the spot where the pain is worst.

Continue light palpation of the patient’s abdomen to detect additional tenderness, rigidity, guarding, or pain. Observe the patient’s facial expression for signs of pain, such as grimacing or wincing. (See Eliciting McBurney’s sign, page 438.) Auscultate the abdomen, noting decreased bowel sounds.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Appendicitis. McBurney’s sign appears within the first 2 to 12 hours after the onset of appendicitis, after initial pain in the epigastric and periumbilical area shifts to the right lower quadrant (McBurney’s point). This persistent pain increases with walking or coughing. Nausea and vomiting may occur from the start. Boardlike abdominal rigidity and rebound tenderness that worsen as the condition progresses accompany cutaneous hyperalgia, fever, constipation or diarrhea, tachycardia, retractive respirations, anorexia, and moderate malaise.

Rupture of the appendix causes sudden cessation of pain. Then, signs and symptoms of peritonitis develop, such as severe abdominal pain, pallor, hypoactive or absent bowel sounds, diaphoresis, and high fever.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Draw blood for laboratory tests such as a complete blood count, including a white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and blood cultures, and prepare the patient for abdominal X-rays to confirm appendicitis. Make sure the patient receives nothing by mouth, and expect to prepare the patient for an appendectomy. Administration of a cathartic or an enema

may cause the appendix to rupture and should be avoided.

may cause the appendix to rupture and should be avoided.

To elicit McBurney’s sign, help the patient into a supine position, with his knees slightly flexed and his abdominal muscles relaxed. Then, palpate deeply and slowly in the right lower quadrant over McBurney’s point—located about 2″ (5 cm) from the right anterior superior spine of the ilium, on a line between the spine and the umbilicus. Point pain and tenderness, a positive McBurney’s sign, indicates appendicitis.

|

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

McBurney’s sign is also elicited in children with appendicitis.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

In elderly patients, McBurney’s sign (as well as other peritoneal signs) may be decreased or absent.

McMurray’s sign

Often an indicator of medial meniscal injury, McMurray’s sign is a palpable, audible click or pop elicited by rotating the tibia on the femur. It results when gentle manipulation of the leg traps torn cartilage and then lets it snap free. Because eliciting this sign forces the surface of the tibial plateau against the femoral condyles, such manipulation is contraindicated in patients with suspected fractures of the tibial plateau or femoral condyles.

A positive McMurray’s sign augments other findings commonly associated with meniscal injury, such as severe joint line tenderness, locking or clicking of the joint, and decreased range of motion.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

After McMurray’s sign has been elicited, find out if the patient is experiencing acute knee pain. Then ask him to describe any recent knee injury. For example, did his injury place twisting external or internal force on the knee, or did he experience blunt knee trauma from a fall? Also, ask about previous knee injury, surgery, prosthetic replacement, or other joint problems such as arthritis, which could have weakened the knee. Ask if anything aggravates or relieves the pain and if he needs assistance to walk.

Have the patient point to the exact area of pain. Assess the leg’s range of motion, both passive and with resistance. Next, check for cruciate ligament stability by noting anterior or posterior movement of the tibia on the femur (drawer sign). Finally, measure the quadriceps muscles in both legs for symmetry. (See Eliciting McMurray’s sign.)

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Meniscal tear. McMurray’s sign can usually be elicited with this type of injury. Associated signs and symptoms include acute knee pain at the medial or lateral joint line (depending on injury site) and decreased range of motion or locking of the knee joint. Quadriceps weakening and atrophy may also occur.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Prepare the patient for knee X-rays, arthroscopy, and arthrography, and obtain any previous X-rays for comparison. If trauma precipitated the knee pain and McMurray’s sign, an effusion or hemarthrosis may occur. Prepare the patient for aspiration of the joint. Immobilize and apply ice to the knee, and apply a cast or a knee immobilizer.

Eliciting McMurray’s sign requires special training and gentle manipulation of the patient’s leg to avoid extending a meniscal tear or locking the knee. If you’ve been trained to elicit McMurray’s sign, place the patient in a supine position and flex his affected knee until his heel nearly touches his buttock. Place your thumb and index finger on either side of the knee joint space and grasp his heel with your other hand. Then rotate the foot and lower leg laterally to test the posterior aspect of the medial meniscus.

|

Keeping his foot in a lateral position, extend the knee to a 90-degree angle to test the anterior aspect of the medial meniscus. A palpable or audible click—a positive McMurray’s sign—indicates injury to meniscal structures.

|

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

McMurray’s sign in adolescents is usually elicited in meniscal tear caused by sports injury. It may also be elicited in children with congenital discoid meniscus.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Instruct the patient to elevate the affected leg and to perform up to 200 straight-leg raises per day. As appropriate, teach him how to use crutches. Also, tell him the prescribed dosage and schedule of any analgesics or anti-inflammatories. Help him adjust to lifestyle changes by providing support and including significant others in teaching.

Melena

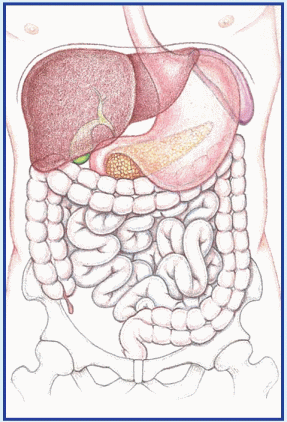

A common sign of upper GI bleeding, melena is the passage of black, tarry stools containing digested blood. Characteristic color results from bacterial degradation and hydrochloric acid acting on the blood as it travels through the GI tract. At least 60 ml of blood is needed to produce this sign. (See Comparing melena to hematochezia, page 440.)

Severe melena can signal acute bleeding and life-threatening hypovolemic shock. Usually, melena indicates bleeding from the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum, although it can also indicate bleeding from the jejunum, ileum, or ascending colon. This sign can also result from swallowing blood, as in epistaxis; from taking certain drugs; or from ingesting alcohol. Because false melena may be caused by ingestion of lead, iron, bismuth, or licorice (which produces black stools without the presence of blood), all black stools should be tested for occult blood.

If the patient is experiencing severe melena, quickly take orthostatic vital signs to detect hypovolemic shock. A decline of 10 mm Hg or more in systolic pressure or an increase of 10 beats/minute or more in pulse rate indicates volume depletion. Quickly examine patient for other signs of shock, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, and cool, clammy skin. Insert a large-bore I.V. catheter to administer replacement fluids and allow blood transfusion. Obtain hematocrit, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, and partial thromboplastin time. Place the patient flat with his head turned to the side and his feet elevated. Administer supplemental oxygen as needed.

If the patient is experiencing severe melena, quickly take orthostatic vital signs to detect hypovolemic shock. A decline of 10 mm Hg or more in systolic pressure or an increase of 10 beats/minute or more in pulse rate indicates volume depletion. Quickly examine patient for other signs of shock, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, and cool, clammy skin. Insert a large-bore I.V. catheter to administer replacement fluids and allow blood transfusion. Obtain hematocrit, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, and partial thromboplastin time. Place the patient flat with his head turned to the side and his feet elevated. Administer supplemental oxygen as needed.Comparing melena to hematochezia

With GI bleeding, the site, amount, and rate of blood flow through the GI tract determine if a patient will develop melena (black, tarry stools) or hematochezia (bright red, bloody stools). Usually, melena indicates upper GI bleeding, and hematochezia indicates lower GI bleeding. However, with some disorders, melena may alternate with hematochezia. This chart helps differentiate these two commonly related signs.

|

Sign | Sites | Characteristics |

Melena | Esophagus, stomach, duodenum; rarely, jejunum, ileum, ascending colon. | Black, loose, tarry stools. Delayed or minimal passage of blood through GI tract. |

Hematochezia | Usually distal to or affecting the colon; rapid hemorrhage of 1 L or more is associated with esophageal, stomach, or duodenal bleeding. | Bright red or dark, mahogany-colored stools; pure blood; blood mixed with formed stool; or bloody diarrhea. Reflects lower GI bleeding or rapid blood loss and passage of undigested blood through GI tract. |

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient’s condition permits, ask when he discovered his stools were black and tarry. Ask about the frequency and quantity of bowel movements. Has he had melena before? Ask about other signs and symptoms, notably hematemesis or hematochezia, and about use of anti-inflammatories, alcohol, or other GI irritants. Also, find out if he has a history of GI lesions. Ask if the patient takes iron supplements, which may also cause black stools. Obtain a drug history, noting the use of warfarin or other anticoagulants.

Next, inspect the patient’s mouth and nasopharynx for evidence of bleeding. Perform an abdominal examination that includes auscultation, palpation, and percussion.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Colon cancer. On the right side of the colon, early tumor growth may cause melena accompanied by abdominal aching, pressure, or cramps. As the disease progresses, the patient develops weakness, fatigue, and anemia. Eventually, he also experiences diarrhea or obstipation, anorexia, weight loss, vomiting, and other signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction.

With a tumor on the left side, melena is a rare sign until late in the disease. Early tumor growth commonly causes rectal bleeding with intermittent abdominal fullness or cramping and rectal pressure. As the disease progresses, the patient may develop obstipation, diarrhea, or pencilshaped stools. At this stage, bleeding from the colon is signaled by melena or bloody stools.

♦ Ebola virus. Melena, hematemesis, and bleeding from the nose, gums, and vagina may occur later with this disorder. Patients usually report abrupt onset of headache, malaise, myalgia, high fever, diarrhea, abdominal pain, dehydration, and lethargy on the fifth day of illness. Pleuritic chest pain, dry hacking cough, and pharyngitis have also been noted. A maculopapular rash develops between days 5 and 7 of the illness.

♦ Esophageal cancer. Melena is a late sign of this malignant neoplastic disease that’s three times more common in men than women. Increasing obstruction first produces painless dysphagia, then rapid weight loss. The patient may experience steady chest pain with substernal fullness, nausea, vomiting, and hematemesis. Other findings include hoarseness, persistent cough (possibly hemoptysis), hiccups, sore throat, and halitosis. In the later stages, signs

and symptoms include painful dysphagia, anorexia, and regurgitation.

and symptoms include painful dysphagia, anorexia, and regurgitation.

♦ Esophageal varices (ruptured). This lifethreatening disorder can produce melena, hematochezia, and hematemesis. Melena is preceded by signs of shock, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and cool, clammy skin. Agitation or confusion signals developing hepatic encephalopathy.

♦ Gastric cancer. Melena and altered bowel habits may occur late with this uncommon cancer. More common findings include insidious onset of upper abdominal or retrosternal discomfort and chronic dyspepsia, which are unrelieved by antacids and exacerbated by food. Anorexia and slight nausea often occur, along with hematemesis, pallor, fatigue, weight loss, and a feeling of abdominal fullness.

♦ Gastritis. Melena and hematemesis are common. The patient may also experience mild epigastric or abdominal discomfort that’s exacerbated by eating; belching; nausea; vomiting; and malaise.

♦ Malaria. Melena may accompany persistent high fever and orthostatic hypotension in severe malaria. Other features include hemoptysis, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, oliguria, and headache, seizures, delirium, or coma. These findings are interspersed throughout the malarial paroxysm—chills, then high fever, and then profuse diaphoresis.

♦ Mallory-Weiss syndrome. This condition is characterized by massive bleeding from the upper GI tract due to a tear in the mucous membrane of the esophagus or the junction of the esophagus and the stomach. Melena and hematemesis follow vomiting. Severe upper abdominal bleeding leads to signs and symptoms of shock, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and cool, clammy skin. The patient may also report epigastric or back pain.

♦ Mesenteric vascular occlusion. This lifethreatening disorder produces slight melena with 2 to 3 days of persistent, mild abdominal pain. Later, abdominal pain becomes severe and may be accompanied by tenderness, distention, guarding, and rigidity. The patient may also experience anorexia, vomiting, fever, and profound shock.

♦ Peptic ulcer. Melena may signal life-threatening hemorrhage from vascular penetration. The patient may also develop decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, hematochezia, and left epigastric pain that’s gnawing, burning, or sharp and may be described as heartburn or indigestion. With hypovolemic shock come tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, dizziness, syncope, and cool, clammy skin.

♦ Small-bowel tumors. These tumors may bleed and produce melena. Other signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, distention, and increasing frequency and pitch of bowel sounds.

♦ Thrombocytopenia. Melena or hematochezia may accompany other manifestations of bleeding tendency: hematemesis, epistaxis, petechiae, ecchymoses, hematuria, vaginal bleeding, and characteristic blood-filled oral bullae. Typically, the patient displays malaise, fatigue, weakness, and lethargy.

♦ Typhoid fever. Melena or hematochezia occurs late in this disorder and may occur with hypotension and hypothermia. Other late findings include mental dullness or delirium, marked abdominal distention and diarrhea, marked weight loss, and profound fatigue.

♦ Yellow fever. Melena, hematochezia, and hematemesis are ominous signs of hemorrhage, a classic feature, which occurs along with jaundice. Other findings include fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, epistaxis, albuminuria, petechiae and mucosal hemorrhage, and dizziness.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs and alcohol. Aspirin, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, or alcohol can cause melena as a result of gastric irritation.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Monitor vital signs, and look closely for signs of hypovolemic shock. For general comfort, encourage bed rest, and keep the patient’s perianal area clean and dry to prevent skin irritation and breakdown. A nasogastric tube may be necessary to assist with drainage of gastric contents and decompression. Prepare him for diagnostic tests, including blood studies, gastroscopy or other endoscopic studies, barium swallow, and upper GI series. Prepare the patient for blood transfusions as indicated by his hematocrit.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Neonates may experience melena neonatorum due to extravasation of blood into the alimentary canal. In older children, melena usually results from peptic ulcer, gastritis, or Meckel’s diverticulum.

Menorrhagia

Abnormally heavy or long menstrual bleeding, menorrhagia may occur as a single episode or a chronic sign. In menorrhagia, bleeding is heavier than the patient’s normal menstrual flow; menstrual blood loss is 80 ml or more per monthly period. A form of dysfunctional uterine bleeding, menorrhagia can result from endocrine and hematologic disorders, stress, and certain drugs and procedures.

Evaluate hemodynamic status by taking orthostatic vital signs. Insert a large-gauge I.V. catheter to begin fluid replacement if the patient shows an increase of 10 beats/minute in pulse rate, a decrease of 10 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure, or other signs of hypovolemic shock, such as pallor, tachycardia, tachypnea, and cool, clammy skin. Place the patient in a supine position with her feet elevated, and administer supplemental oxygen as needed.

Evaluate hemodynamic status by taking orthostatic vital signs. Insert a large-gauge I.V. catheter to begin fluid replacement if the patient shows an increase of 10 beats/minute in pulse rate, a decrease of 10 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure, or other signs of hypovolemic shock, such as pallor, tachycardia, tachypnea, and cool, clammy skin. Place the patient in a supine position with her feet elevated, and administer supplemental oxygen as needed.Use menstrual pads to obtain information related to the quality and quantity of bleeding. Then prepare the patient for a pelvic examination to help determine the cause of bleeding.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

When the patient’s condition permits, obtain a history. Determine her age at menarche, the average duration of menstrual periods, and the interval between them. Establish the date of the patient’s last menses, and ask about any recent changes in her normal menstrual pattern. Have the patient describe the character and amount of bleeding. For example, how many pads or tampons does the patient use? Has she noted clots or tissue in the blood? Also ask about the development of other signs and symptoms before and during the menstrual period.

Next, ask if the patient is sexually active. Does she use a method of birth control? If so, what kind? Could the patient be pregnant? Be sure to note the number of pregnancies, the outcome of each, and any pregnancy-related complications. Find out the dates of her most recent pelvic examination and Papanicolaou smear and the details of any previous gynecologic infections or neoplasms. Also, be sure to ask about any previous episodes of abnormal bleeding and the outcome of any treatment. If possible, obtain a pregnancy history of the patient’s mother, and determine if the patient was exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. (This drug has been linked to vaginal adenosis.)

Be sure to ask the patient about her general health and medical history. Note particularly if the patient or her family has a history of thyroid, adrenal, or hepatic disease; blood dyscrasias; or tuberculosis because these may predispose the patient to menorrhagia. Also, ask about the patient’s past surgical procedures and any recent emotional stress. Find out if the patient has undergone X-ray or other radiation therapy, because this may indicate prior treatment for menorrhagia. Obtain a thorough drug and alcohol history, noting the use of anticoagulants or aspirin. Perform a pelvic examination, and obtain blood and urine samples for pregnancy testing.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Blood dyscrasias. Menorrhagia is one of several possible signs of a bleeding disorder. Other possible associated findings include epistaxis, bleeding gums, purpura, hematemesis, hematuria, and melena.

♦ Endometriosis. Menorrhagia may be a sign of this disorder, in which endometrial tissue is found outside the lining of the uterine cavity. However, the classic symptom is dysmenorrhea. Other findings depend on the location of the ectopic tissue outside the uterus but may include dyspareunia, suprapubic pain, dysuria, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, cyclic pelvic pain, and infertility. Often a tender, fixed adnexal mass is palpable on bimanual examination.

♦ Hypothyroidism. Menorrhagia is a common early sign and is accompanied by such nonspecific findings as fatigue, cold intolerance, constipation, and weight gain despite anorexia. As hypothyroidism progresses, intellectual and motor activity decrease; the skin becomes dry, pale, cool, and doughy; the hair becomes dry and sparse; and the nails become thick and brittle. Myalgia, hoarseness, decreased libido, and infertility commonly occur. Eventually, the patient develops a characteristic dull, expressionless face and edema of the face, hands, and feet.

Also, deep tendon reflexes are delayed, and bradycardia and abdominal distention may occur.

♦ Uterine fibroids. Menorrhagia is the most common sign, but other forms of abnormal uterine bleeding as well as dysmenorrhea or

leukorrhea, can also occur. Possible related findings include abdominal pain, a feeling of abdominal heaviness, backache, constipation, urinary urgency or frequency, and an enlarged uterus, which is usually nontender.

leukorrhea, can also occur. Possible related findings include abdominal pain, a feeling of abdominal heaviness, backache, constipation, urinary urgency or frequency, and an enlarged uterus, which is usually nontender.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Use of a hormonal contraceptive may cause sudden onset of profuse, prolonged menorrhagia. Anticoagulants have also been associated with excessive menstrual flow. Injectable or implanted contraceptives may cause menorrhagia in some women.

♦ Intrauterine devices. Menorrhagia can result from the use of intrauterine contraceptive devices.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Continue to monitor the patient closely for signs of hypovolemia. Encourage the patient to maintain adequate fluid intake. Monitor intake and output, and estimate uterine blood loss by recording the number of sanitary napkins or tampons used during an abnormal period and comparing this with usage during a normal period. To help decrease blood flow, encourage the patient to rest and to avoid strenuous activities. Obtain blood samples for hematocrit, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and international normalized ratio levels.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Irregular menstrual function in young girls may be accompanied by hemorrhage and resulting anemia.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

In postmenopausal women, menorrhagia cannot occur. In such patients, vaginal bleeding is usually caused by endometrial atrophy. Malignancy must be ruled out.

Metrorrhagia

Metrorrhagia—uterine bleeding that occurs irregularly between menstrual periods—is usually light, although it can range from staining to hemorrhage. Usually, this common sign reflects slight physiologic bleeding from the endometrium during ovulation. However, metrorrhagia may be the only indication of an underlying gynecologic disorder and can also result from stress, drugs, treatments, and intrauterine devices.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Begin your evaluation by obtaining a thorough menstrual history. Ask the patient when she began menstruating and about the duration of menstrual periods, the interval between them, and the average number of tampons or pads she uses. When does metrorrhagia usually occur in relation to her period? Does she experience other signs or symptoms? Find out the date of her last menses, and ask about any other recent changes in her normal menstrual pattern. Get details of any previous gynecologic problems. If applicable, obtain a contraceptive and obstetric history. Record the dates of her last Papanicolaou smear and pelvic examination. Ask the patient when she last had sex and whether or not it was protected. Next, ask about her general health and any recent changes. Is she under emotional stress? If possible, obtain a pregnancy history of the patient’s mother. Was the patient exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol? (This drug has been linked to vaginal adenosis.)

Perform a pelvic examination if indicated, and obtain blood and urine samples for pregnancy testing.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Cervicitis. This nonspecific infection may cause spontaneous bleeding, spotting, or posttraumatic bleeding. Assessment reveals red, granular, irregular lesions on the external cervix. Purulent vaginal discharge (with or without odor), lower abdominal pain, and fever may occur.

♦ Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Abnormal uterine bleeding not caused by pregnancy or major gynecologic disorders usually occurs as metrorrhagia, although menorrhagia is possible. Bleeding may be profuse or scant, intermittent or constant.

♦ Endometrial polyps. In most patients, this disorder causes abnormal bleeding, usually intermenstrual or postmenopausal; however, some patients do remain asymptomatic.

♦ Endometriosis. Metrorrhagia (usually premenstrual) may be the only indication of this disorder, or it may accompany cyclical pelvic discomfort, infertility, and dyspareunia. A tender, fixed adnexal mass may be palpable on bimanual examination.

♦ Endometritis. This disorder causes metrorrhagia, purulent vaginal discharge, and

enlargement of the uterus. It also produces fever, lower abdominal pain, and abdominal muscle spasm.

enlargement of the uterus. It also produces fever, lower abdominal pain, and abdominal muscle spasm.

♦ Gynecologic cancer. Metrorrhagia is commonly an early sign of cervical or uterine cancer. Later, the patient may experience weight loss, pelvic pain, fatigue and, possibly, an abdominal mass.

♦ Syphilis. Primary- or secondary-stage syphilis may cause metrorrhagia and postcoital bleeding. In primary syphilis, one or more usually painless chancres erupt on the genitalia and possibly other areas. In secondary syphilis, generalized lymphadenopathy may appear, along with a rash on the arms, trunk, palms, soles, face, and scalp.

♦ Uterine leiomyomas. Besides metrorrhagia, these tumors may cause increasing abdominal girth and heaviness in the abdomen, constipation, and urinary frequency or urgency. The patient may report pain if the uterus attempts to expel the tumor through contractions and if the tumors twist or necrose after circulatory occlusion or infection, but many women with leiomyomas are asymptomatic.

♦ Vaginal adenosis. This disorder commonly produces metrorrhagia. Palpation reveals roughening or nodules in affected vaginal areas.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Anticoagulants and oral, injectable, or implanted contraceptives may cause metrorrhagia.

♦ Surgery and procedures. Cervical conization and cauterization may cause metrorrhagia.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Encourage bed rest to reduce bleeding. Give an analgesic for discomfort.

Miosis

Miosis—pupillary constriction caused by contraction of the sphincter muscle in the iris— occurs normally as a response to fatigue, increased light, or administration of a miotic; as part of the eye’s accommodation reflex; and as part of the aging process (pupil size steadily decreases from adolescence to about age 60). However, it can also stem from an ocular or neurologic disorder, trauma, use of a systemic drug, or contact lens overuse. A rare form of miosis—Argyll Robertson pupils—can stem from tabes dorsalis and diverse neurologic disorders. Occurring bilaterally, these miotic (often pinpoint), unequal, and irregularly shaped pupils don’t dilate properly with mydriatic use and fail to react to light, although they do constrict on accommodation.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Begin by asking the patient if he has experienced other ocular symptoms, and have him describe their onset, duration, and intensity. Does he wear contact lenses? During your history, be sure to ask about trauma, serious systemic disease, and use of topical and systemic drugs.

Next, perform a thorough eye examination. Test visual acuity in each eye, with and without correction, paying particular attention to blurred or decreased vision in the miotic eye. Examine and compare both pupils for size (many persons have a normal discrepancy), color, shape, reaction to light, accommodation, and consensual light response. Examine both eyes for additional signs, and then evaluate extraocular muscle function by assessing the six cardinal fields of gaze.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Cerebrovascular arteriosclerosis. Miosis is usually unilateral, depending on the site and extent of vascular damage. Other findings include visual blurring, slurred speech or possibly aphasia, loss of muscle tone, memory loss, vertigo, and headache.

♦ Cluster headache. Ipsilateral miosis, tearing, conjunctival injection, and ptosis commonly accompany a severe cluster headache, along with facial flushing and sweating, bradycardia, restlessness, and nasal stuffiness or rhinorrhea.

♦ Corneal foreign body. Miosis in the affected eye occurs with pain, a foreign-body sensation, slight vision loss, conjunctival injection, photophobia, and profuse tearing.

♦ Corneal ulcer. Miosis in the affected eye appears with moderate pain, visual blurring and possibly some vision loss, and diffuse conjunctival injection.

♦ Horner’s syndrome. Moderate miosis is common in this neurologic syndrome and occurs ipsilaterally to the spinal cord lesion. Related ipsilateral findings include a sluggish pupillary reflex, slight enophthalmos, moderate ptosis, facial anhidrosis, transient conjunctival injection, and vascular headache. When the

syndrome is congenital, the iris on the affected side may appear lighter.

syndrome is congenital, the iris on the affected side may appear lighter.

♦ Hyphema. Usually the result of blunt trauma, hyphema can cause miosis with moderate pain, visual blurring, diffuse conjunctival injection, and slight eyelid swelling. The eyeball may feel harder than normal.

♦ Iritis (acute). Miosis typically occurs in the affected eye along with decreased pupillary reflex, severe eye pain, photophobia, visual blurring, conjunctival injection and, possibly, pus accumulation in the anterior chamber. The eye appears cloudy, the iris bulges, and the pupil is constricted on ophthalmic examination.

♦ Neuropathy. Two forms of neuropathy occasionally produce Argyll Robertson pupils. With diabetic neuropathy, related effects include paresthesia and other sensory disturbances, extremity pain, orthostatic hypotension, impotence, incontinence, and leg muscle weakness and atrophy.

With alcoholic neuropathy, related effects include progressive, variable muscle weakness and wasting, various sensory disturbances, and hypoactive deep tendon reflexes.

♦ Parry-Romberg syndrome. This facial hemiatrophy typically produces miosis, sluggish pupillary reflexes, enophthalmos, nystagmus, ptosis, and different-colored irises.

♦ Pontine hemorrhage. Bilateral miosis is characteristic, along with rapid onset of coma, total paralysis, decerebrate posture, absent doll’s eye sign, and a positive Babinski’s sign.

♦ Tabes dorsalis. This tertiary form of syphilis is marked by Argyll Robertson pupils, a wide base ataxic gait, paresthesia, loss of proprioception, analgesia, thermanesthesia, Charcot’s joints, incontinence and, possibly, impotence.

♦ Uveitis. Anterior uveitis commonly produces miosis in the affected eye, moderate-to-severe eye pain, severe conjunctival injection, photophobia, and pus in the anterior chamber.

With posterior uveitis, miosis is accompanied by gradual onset of eye pain, photophobia, visual floaters, visual blurring, conjunctival injection and, commonly, distorted pupil shape.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Chemical burns. An opaque cornea may make miosis hard to detect. However, chemical burns may also cause moderate-to-severe pain, diffuse conjunctival injection, inability to keep the eye open, visual blurring, and blistering.

♦ Drugs. Such topical drugs as acetylcholine, carbachol, echothiophate iodide, and pilocarpine are used to treat eye disorders specifically for their miotic effect. Such systemic drugs as barbiturates, cholinergics, anticholinesterases, clonidine hydrochloride (overdose), opiates, and reserpine also cause miosis, as does deep anesthesia.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Because any ocular abnormality can be a source of fear and anxiety, reassure and support the patient. Clearly explain any diagnostic tests ordered, which may include a complete ophthalmologic examination or a neurologic workup.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Miosis is common in neonates, simply because they’re asleep or sleepy most of the time. Bilateral miosis occurs with congenital microcoria, an uncommon bilateral disease transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait and marked by the absence of the dilator muscle of the pupil. At birth, these infants have pupils less than 2 mm and seem to gaze far away.

Moon face

Moon face, a distinctive facial adiposity, usually indicates hypercortisolism resulting from ectopic or excessive pituitary production of corticotropin, adrenal adenoma or carcinoma, or long-term glucocorticoid therapy. Its typical characteristics include marked facial roundness and puffiness, a double chin, a prominent upper lip, and full supraclavicular fossae. Although the presence of moon face doesn’t help differentiate causes of hypercortisolism, it does indicate a need for diagnostic testing.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Ask the patient when he first noticed his facial adiposity, and try to obtain a preonset photograph to help evaluate the extent of the change.

Ask about weight gain and any personal or family history of endocrine disorders, obesity, or cancer. Has the patient noticed any fatigue, irritability, depression, or confusion? If the patient is a female of childbearing age, determine the date of her last menses and whether she’s experienced any menstrual irregularities.

If the patient is receiving a glucocorticoid, ask the name of the drug, dosage and schedule, route of administration, and reason for therapy. Also ask if the dosage has ever been modified and, if so, when and why.

Take the patient’s vital signs, weight, and height. Assess the patient’s overall appearance for other characteristic signs of hypercortisolism, including virilism in a female or gynecomastia in a male. Also assess for purple striae on the skin, muscle weakness due to loss of muscle mass from increased catabolism, and skeletal growth retardation in children.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Hypercortisolism. Moon face varies in severity, depending on the degree of cortisol excess and weight gain. The patient typically exhibits buffalo hump, truncal obesity with slender arms and legs, and thin, transparent skin with purple striae and ecchymoses. Other cushingoid features include acne, diaphoresis, fatigue, muscle wasting and weakness, poor wound healing, elevated blood pressure, and personality changes.

In addition to these findings, a woman may experience hirsutism and amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea; a man may experience gynecomastia and impotence.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Most cases (more than 99%) of moon face result from prolonged use of a glucocorticoid, such as cortisone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, or prednisone.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Relieve the patient’s concern about his body image by explaining that moon face and other disconcerting cushingoid effects can usually be corrected by treating the underlying disorder or by discontinuing or modifying glucocorticoid therapy. Explain to the patient that he should only discontinue or modify glucocorticoid therapy as directed by the physician.

Clearly explain to the patient any diagnostic tests ordered. These may include serum and urine 17-hydroxycorticosteroid studies; a 2-day, low-dose dexamethasone test followed by a 2-day, high-dose dexamethasone test; plasma corticotropin studies; and a corticotropin-releasing hormone test.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Moon face is rare in children. In an infant or a young child, it usually indicates adrenal adenoma or carcinoma or, rarely, cri du chat syndrome. After age 7, it usually indicates abnormal pituitary secretion of corticotropin in bilateral adrenal hyperplasia.

Mouth lesions

Mouth lesions include ulcers (the most common type), cysts, firm nodules, hemorrhagic lesions, papules, vesicles, bullae, and erythematous lesions. They may occur anywhere on the lips, cheeks, hard and soft palate, salivary glands, tongue, gingivae, or mucous membranes. Many are painful and can be readily detected. Some, however, are asymptomatic; when they occur deep in the mouth, they may be discovered only through a complete oral examination. (See Common mouth lesions.)

Mouth lesions can result from trauma, infection, systemic disease, drug use, or radiation therapy.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Begin your evaluation with a thorough history. Ask the patient when the lesions appeared and whether he has noticed any pain, odor, or drainage. Also ask about associated complaints, particularly skin lesions. Obtain a complete drug history, including drug allergies and antibiotic use, and a complete medical history. Note especially any malignancy, sexually transmitted disease, I.V. drug use, recent infection, or trauma. Ask about his dental history, including oral hygiene habits, frequency of dental examinations, and the date of his most recent dental visit.

Next, perform a complete oral examination, noting lesion sites and character. Examine the patient’s lips for color and texture. Inspect and palpate the buccal mucosa and tongue for color, texture, and contour; note especially any painless ulcers on the sides or base of the tongue. Hold the tongue with a piece of gauze, lift it, and examine its underside and the floor of the mouth. Depress the tongue with a tongue blade, and examine the oropharynx. Inspect the teeth and gums, noting missing, broken, or discolored teeth; dental caries; excessive debris; and bleeding, inflamed, swollen, or discolored gums.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree