(1)

Department of Pathology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

Keywords

Malignant lymphomaDiffuse large B-cell lymphoma with sclerosisAnaplastic large cell lymphomaMALT lymphomaMarginal zone lymphomaLymphoblastic lymphomaHodgkin lymphomaThe mediastinum is a common site of involvement for lymphoproliferative disorders. The most common types of lymphomas involving the mediastinum are Hodgkin lymphoma, diffuse large cell lymphoma, and lymphoblastic lymphoma, but almost any type of malignant lymphoma can involve the mediastinum. B-cell lymphomas are the most common type of lymphoma encountered in this location; they may commonly involve the mediastinal compartments as part of systemic disease. In more recent years, however, a primary B-cell lymphoma originating from B-cell precursors native to the thymus has been recognized and termed primary mediastinal diffuse large cell lymphoma. The majority of primary mediastinal lymphomas arise in the anterior mediastinal compartment, but lymphomas also can arise from lymph nodes in the middle or posterior compartment. Such lymphomas are most often of the B-cell type and can be of the follicular type or diffuse. Rarely, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, mantle zone lymphoma, plasmablastic lymphoma, and other rare types of lymphomas may also present as a primary tumor in the mediastinum.

7.1 Primary Mediastinal Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphomas (LBCLs) have been regarded as a discrete clinicopathologic entity that most commonly affects young adults in their third decade of life and shows a predilection for women. The tumors are usually bulky and present as a localized mass in the anterior mediastinum (Figs. 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 7.5, 7.6, 7.7, and 7.8). The mass is most often limited to the mediastinum but may invade locally into the lung, pleura, and pericardium. The absence of lymph node or bone marrow involvement is required to distinguish it from secondary involvement by systemic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The tumors characteristically express B-cell antigens but lack immunoglobulins; however, immunoglobulin genes are clonally rearranged. It has been postulated that the tumors may be derived from a native thymic B-cell population located in the thymic medulla. Although initially found to be a highly aggressive tumor, primary mediastinal LBCL responds well to intensive chemotherapy. Infiltration of adjacent thoracic structures carries a worse prognosis. Primary mediastinal diffuse large cell lymphoma can adopt a variety of unusual morphologic appearances that make diagnosis challenging. Application of immunohistochemical stains will generally allow proper identification and separation from other similar or related processes.

Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of the mediastinum can have many different and distinct morphologic appearances:

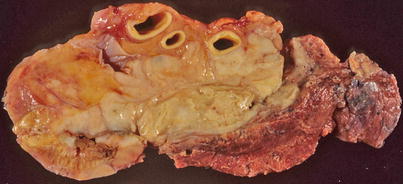

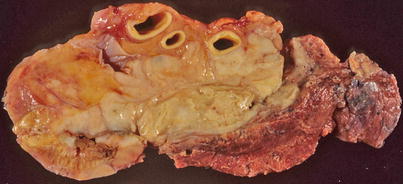

Fig. 7.1

Gross appearance of primary mediastinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) shows a solid, tan-white, homogeneous, and rubbery cut surface with focal areas of hemorrhage. In rare instances, the tumors may show secondary cystic changes. Advanced cases will show infiltration of the pleura and pericardium, with entrapment of mediastinal structures, including large vessels

Fig. 7.2

Cut surface of primary mediastinal DLBCL shows focal infiltration of the pleura and lung, with encasement of large vessels in the mediastinum

Fig. 7.3

A core biopsy of the mediastinum is often the first step for making the diagnosis of mediastinal DLBCL. A common artifact produced by the biopsy procedure is extensive crushing of the tumor cells, which makes the process difficult to recognize as a lymphoid malignancy

Fig. 7.4

Higher magnification of core biopsy of mediastinal DLBCL shows scattered round or oval cells with extensive crushing artifact embedded in abundant collagenous stroma

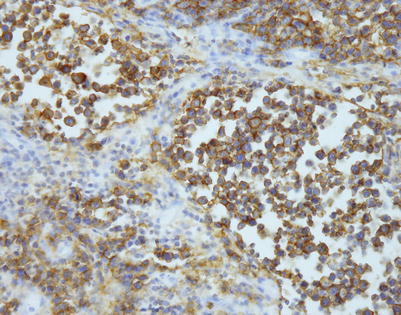

Fig. 7.5

Immunohistochemistry can be of great value in this setting by demonstrating strong positivity in the cellular clusters with lymphoid markers, such as CD45, CD20, and CD79a, and negative staining for other differentiation markers, such as cytokeratins, melanoma markers, and germ cell tumor markers

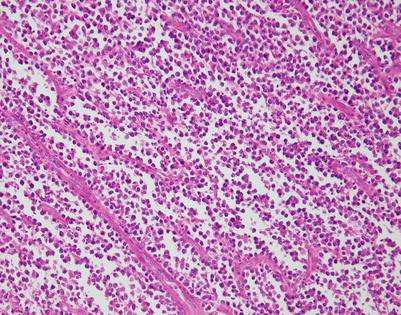

Fig. 7.6

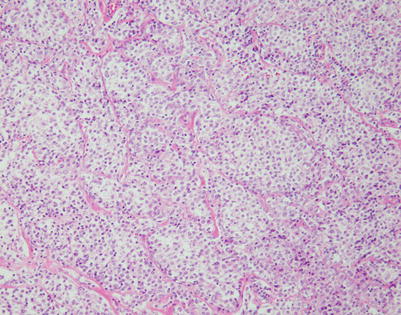

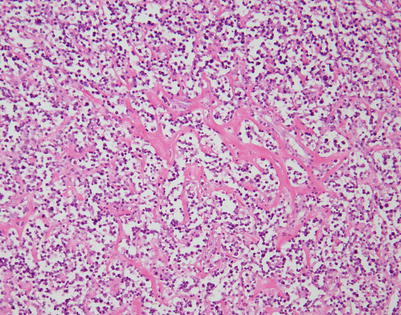

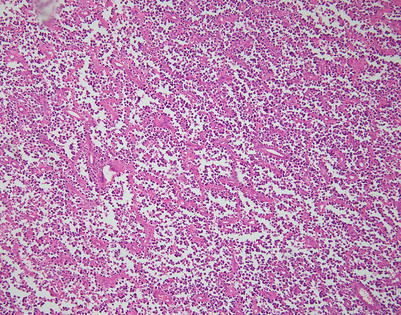

Mediastinal DLBCL on scanning magnification shows sheets of discohesive tumor cells dotted by a few small vessels reminiscent of DLBCL at other sites

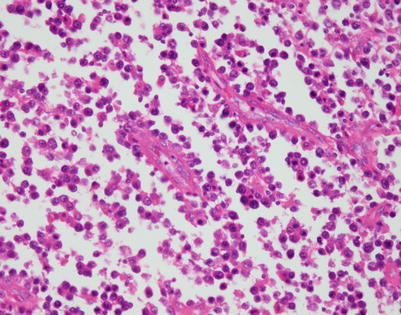

Fig. 7.7

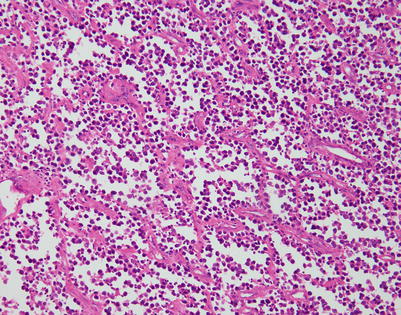

On higher magnification, mediastinal DLBCL displays a sheetlike pattern composed of a homogeneous population of large, lymphoid cells

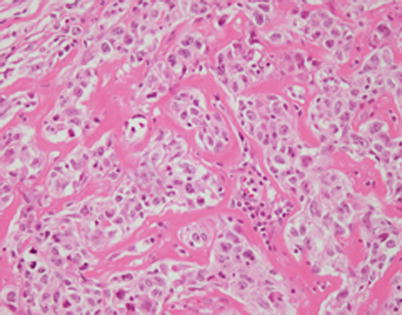

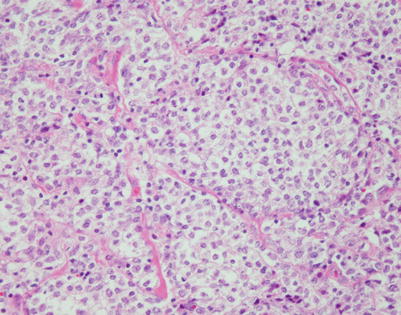

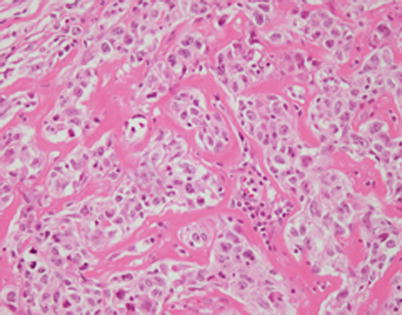

Fig. 7.8

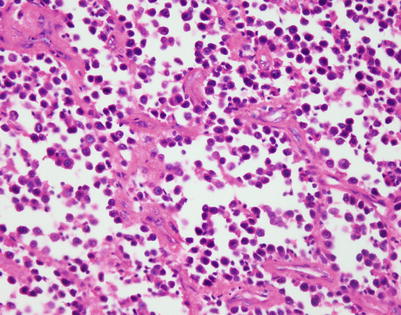

A high-power view of the field in Fig. 7.7 (mediastinal DLBCL) shows a population of large, lymphoid cells with clumped chromatin, eosinophilic nucleoli, and scattered mitotic figures

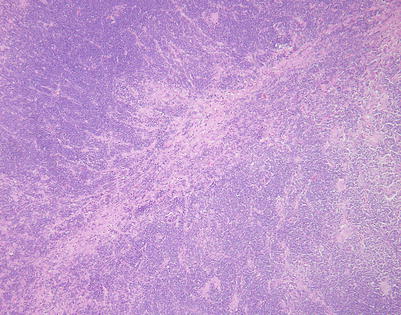

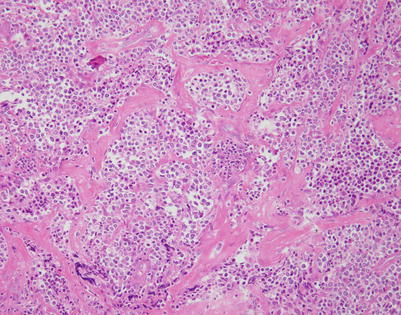

Fig. 7.9

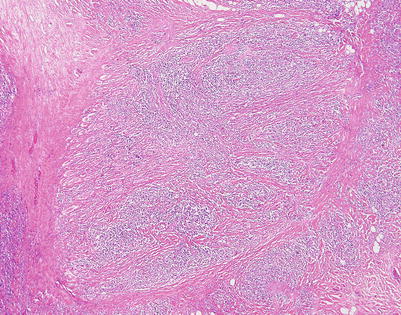

Mediastinal DLBCL often can display a significant amount of stromal sclerosis. In the past, such cases were termed “sclerosing diffuse large cell lymphoma of the mediastinum.” Because of the compartmentalizing effect of the fibrosis, the tumors were commonly mistaken for other types of malignancy, including thymic carcinoma, seminoma, melanoma, and metastases of tumors from other organs

Fig. 7.10

On higher magnification, the example in Fig. 7.9 shows nests of large tumor cells separated by broad bands of acellular collagen

Fig. 7.11

The fibrosing theme in mediastinal DLBCL can vary considerably from patient to patient and in different areas within the same neoplasm. This tumor shows a more haphazard pattern of diffuse sclerosis, without a highly compartmentalized appearance

Fig. 7.12

On higher magnification, the example in Fig. 7.11 shows a diffuse pattern of fibrosis that breaks up the cells into small, irregular strands and single-file configurations

Fig. 7.13

A higher magnification from the field in Fig. 7.11 illustrates the lymphoid nature of the tumor cells, with the large nuclei showing dense nuclear chromatin and prominent nucleoli

Fig. 7.14

Another example of mediastinal DLBCL with striking compartmentalization by fibrous septa. Bands of acellular collagen are seen circumscribing round to oval nests of large tumor cells

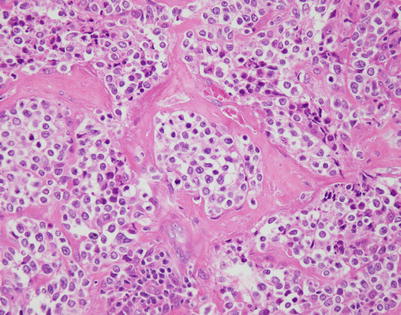

Fig. 7.15

At higher magnification, mediastinal DLBCL with fibrosis shows irregular round to oval nests of tumor cells separated by thin bands of fibrous connective tissue

Fig. 7.16

A higher magnification from the same area as in Fig. 7.15 shows large tumor cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and nuclear membrane irregularities surrounded by a rim of clear cytoplasm. The cells can resemble seminoma, melanoma, or carcinoma cells. Immunohistochemical stains are required to establish the correct diagnosis

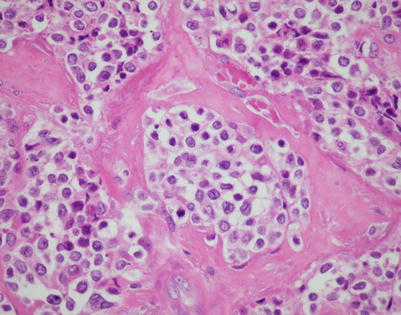

Fig. 7.17

A different pattern of sclerosis is seen in this mediastinal DLBCL, which shows a tumor island surrounded by broad bands of fibrous tissue. The tumor island itself shows subtle compartmentalization by more delicate, thin bands of fibrous tissue

Fig. 7.18

At higher magnification, the DLBCL in Fig. 7.17 shows a fine pattern of sclerosis resulting in smaller “nests” of tumor cells in which the cells appear small because of compression from the surrounding connective tissue

Fig. 7.19

Another example of stromal sclerosis in mediastinal DLBCL, in which irregularly distributed foci of stromal sclerosis separate broad expanses of tumor cells

Fig. 7.20

Higher magnification from the areas of fibrosis in mediastinal DLBCL shows discrete nests of large tumor cells surrounded by thick bands of acellular collagen

Fig. 7.21

A higher magnification from the same area as in Fig. 7.20 shows irregular strands and small nests of large tumor cells

Fig. 7.22

Higher magnification from the same case of mediastinal DLBCL shows detail of the tumor cells, with large nuclei displaying a clumped chromatin pattern; often, multiple nucleoli are surrounded by a scant rim of amphophilic cytoplasm

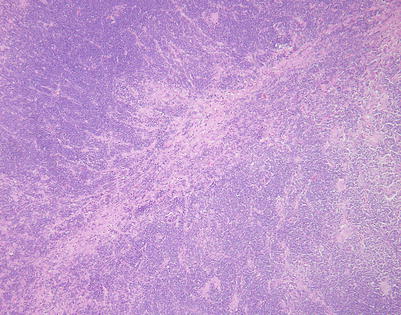

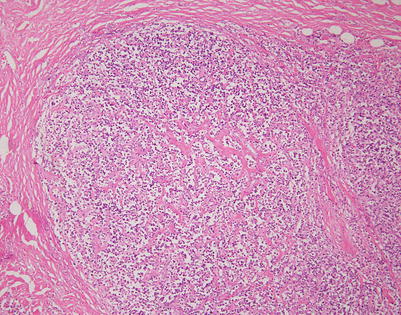

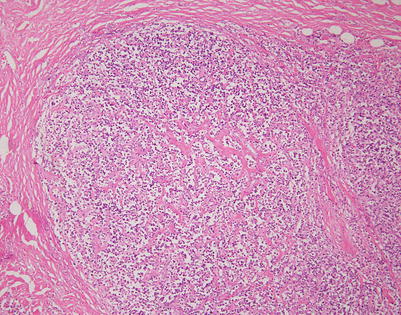

Fig. 7.23

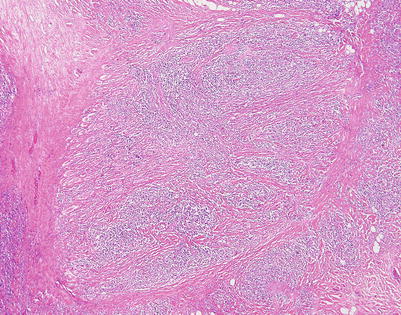

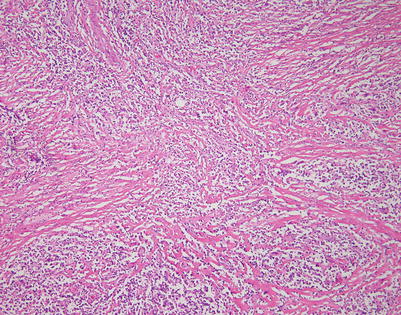

This example of mediastinal DLBCL shows a more advanced pattern of stromal sclerosis. Scanning magnification shows a residual nodule containing a round cell infiltrate surrounded by fibrous tissue

Fig. 7.24

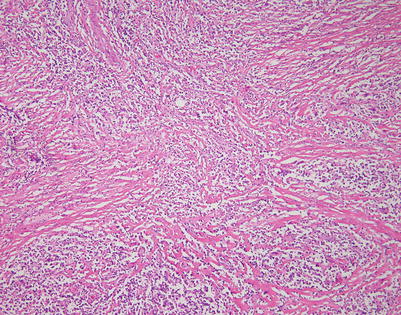

Higher magnification from mediastinal DLBCL shows a linear pattern of sclerosis, with parallel strands of acellular connective tissue deposited between the tumor cells

Fig. 7.25

A reticular pattern of fibrous deposition is seen on higher magnification in this mediastinal DLBCL. The tumor cells are compressed by the surrounding collagenous tissue, making them appear smaller

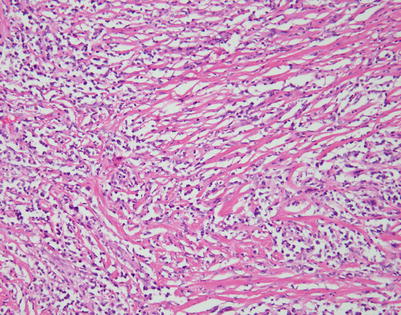

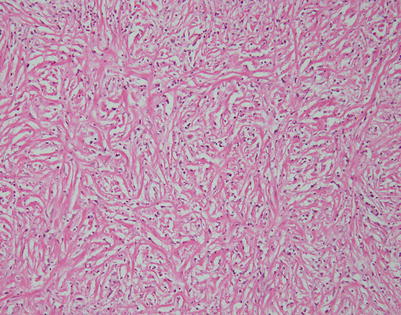

Fig. 7.26

This example of mediastinal DLBCL shows a diffuse reticular pattern of stromal sclerosis. The linear deposition of intercellular collagen results in ropelike strands of connective tissue that impart the lesion with a superficial resemblance to a solitary fibrous tumor

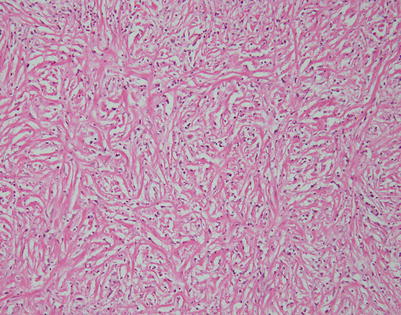

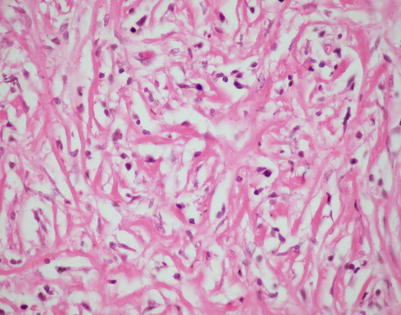

Fig. 7.27

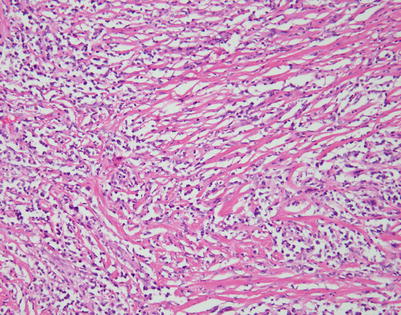

A higher magnification from the same mediastinal DLBCL as in Fig. 7.26 shows artifactual distortion of the tumor cells, which display elongated and hyperchromatic nuclei. It may be very difficult to recognize the lesion as lymphoid under these circumstances. Immunohistochemical stains for B-cell markers, however, will usually demonstrate the lymphoid nature of the tumor cells

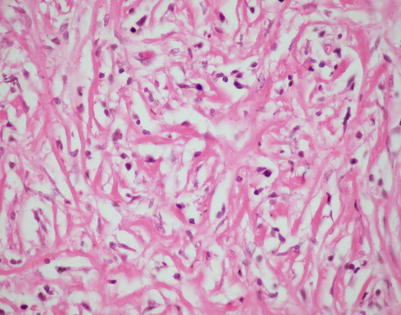

Fig. 7.28

Another example of an advanced stage of sclerosis in mediastinal DLBCL shows a pattern of circumferential deposition of collagen around individual tumor cells

Fig. 7.29

Higher magnification from the field in Fig. 7.28 shows atypical lymphoid cells lying in individual lacunae that are surrounded by dense, acellular collagenous tissue

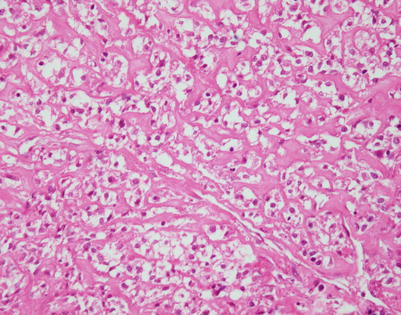

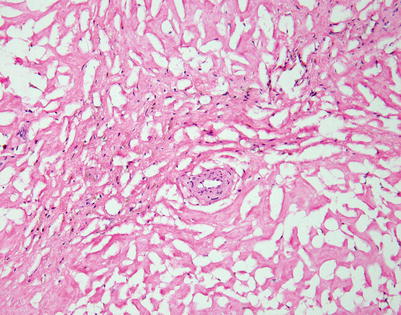

Fig. 7.30

The end stage of the fibrosing process in mediastinal DLBCL is characterized by almost complete disappearance of the tumor cells; a delicate scaffolding is composed of empty spaces surrounded by acellular collagen

Fig. 7.31

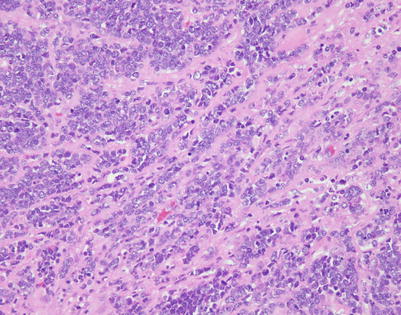

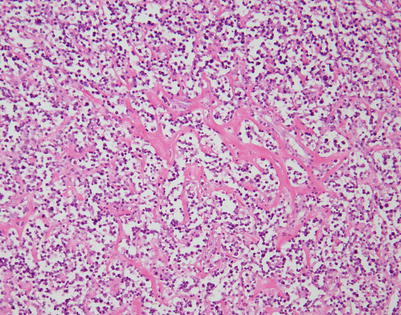

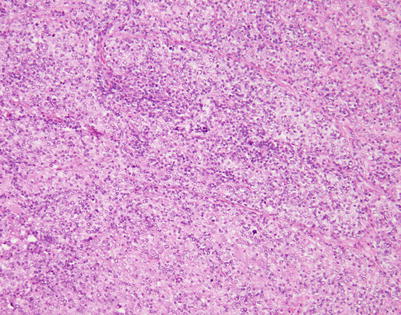

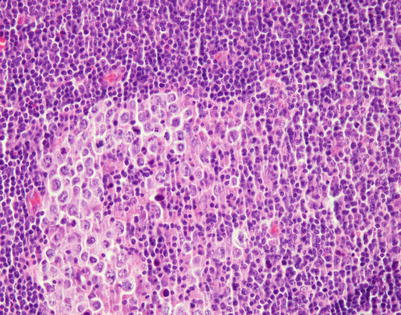

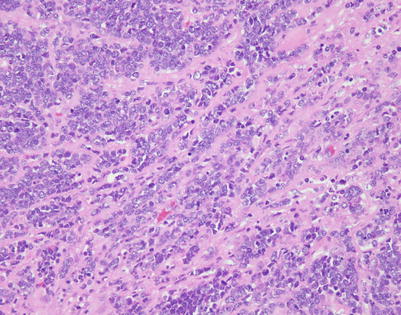

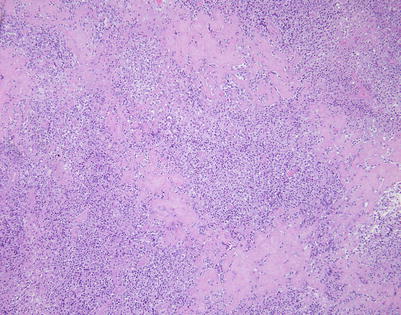

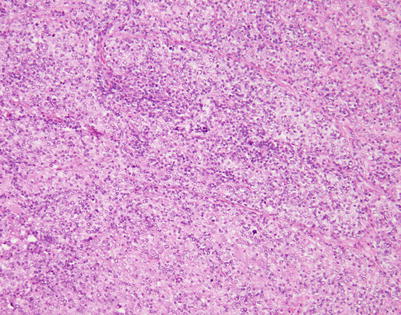

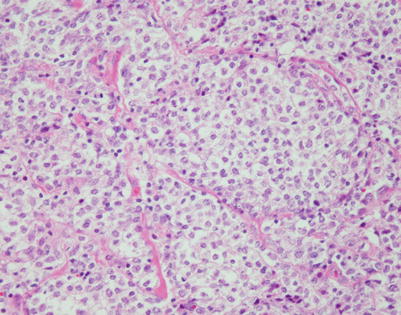

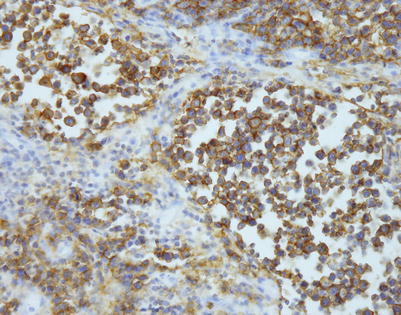

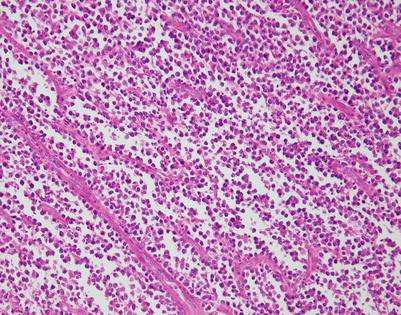

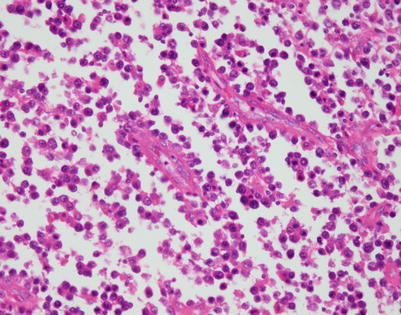

T-cell-rich mediastinal DLBCL is another variant of primary mediastinal lymphoma, characterized by an abundance of reactive T lymphocytes scattered in the background, admixed with the neoplastic large B-cell elements

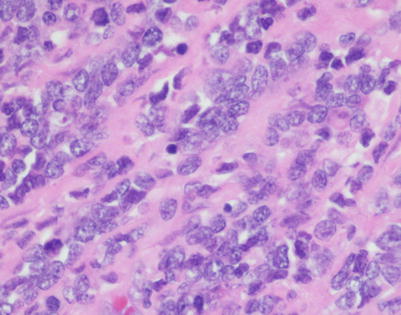

Fig. 7.32

At higher magnification, T-cell-rich mediastinal DLBCL shows numerous small T lymphocytes, which partially overshadow the larger B cells scattered in the background. Immunohistochemical stains will permit easy separation of the two cell types

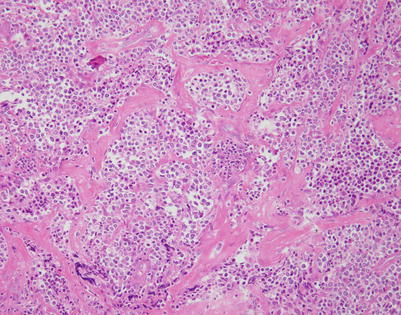

Fig. 7.33

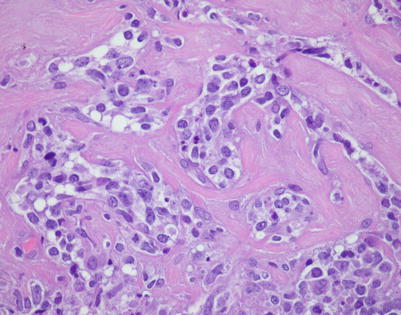

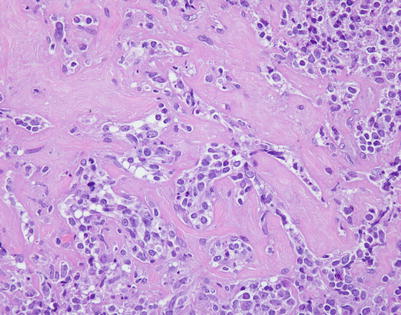

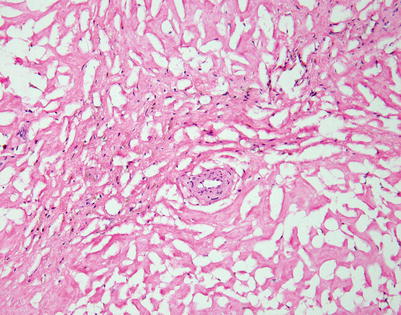

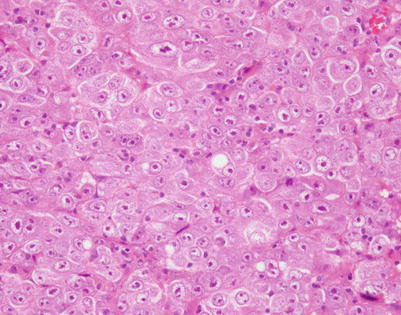

Rare mediastinal lymphomas can be characterized by large tumor cells that contain very prominent and abundant clear cytoplasm. Tumors displaying clear cell features can sometimes mimic metastases from other clear cell tumors such as clear cell renal cell carcinoma. The tumors can show fine fibrovascular septa, which separate the tumor cells into distinct lobules

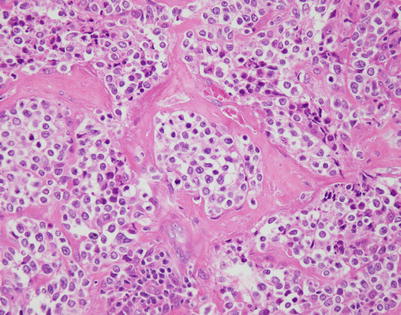

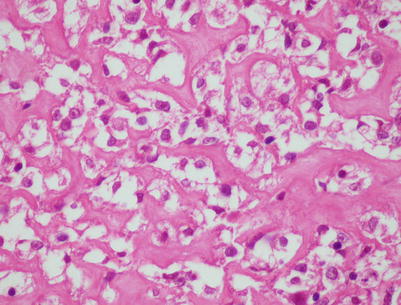

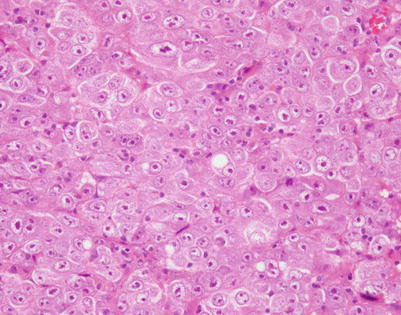

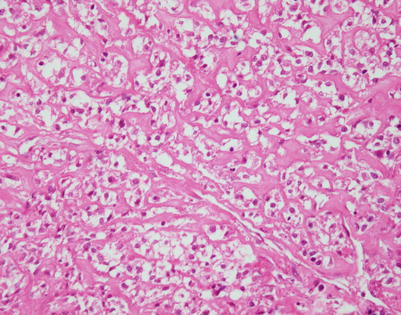

Fig. 7.34

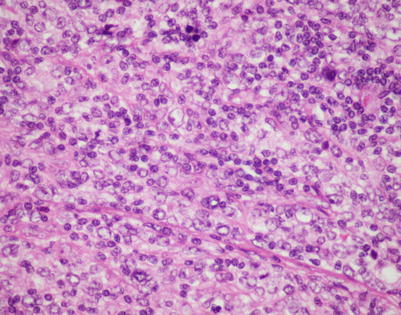

Higher magnification of mediastinal DLBCL, clear cell type, shows nests of large, round tumor cells with abundant clear cytoplasm. In this case, the tumor cells were strongly positive for CD45 and CD20

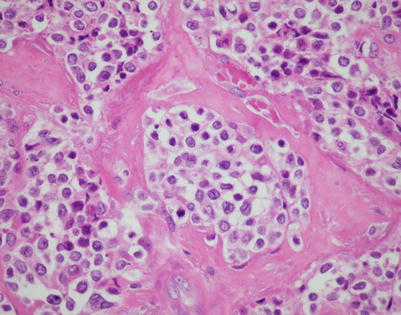

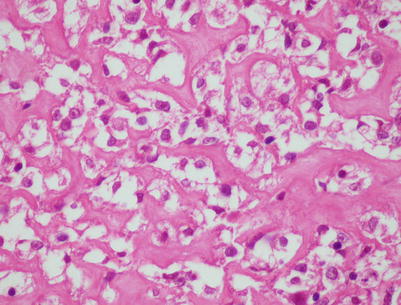

Fig. 7.35

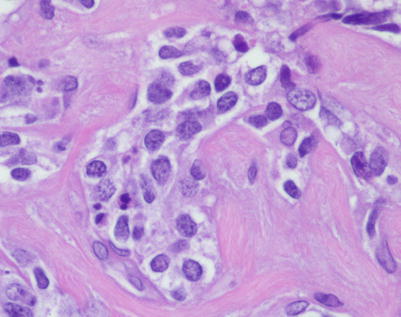

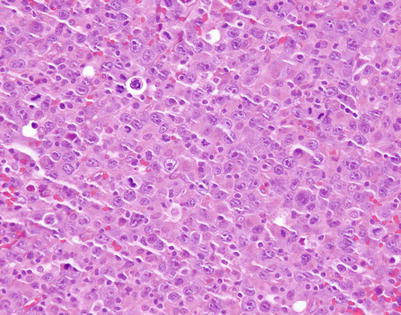

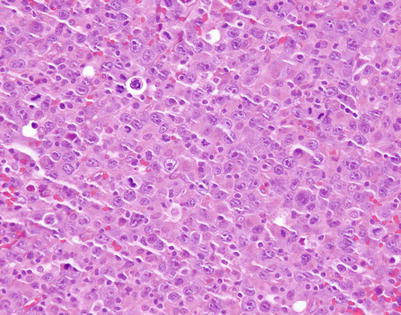

Mediastinal DLBCL can often show cells with large nuclei that have very prominent, inclusion-like eosinophilic nucleoli, similar to what the old literature termed “immunoblastic” lymphoma

Fig. 7.36

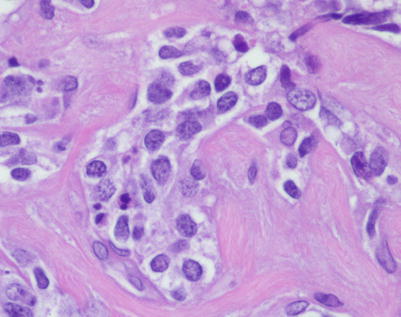

Higher magnification of mediastinal DLBCL with “immunoblastic” features shows cells with large nuclei and very prominent eosinophilic nucleoli surrounded by an ample rim of eosinophilic cytoplasm

Fig. 7.37

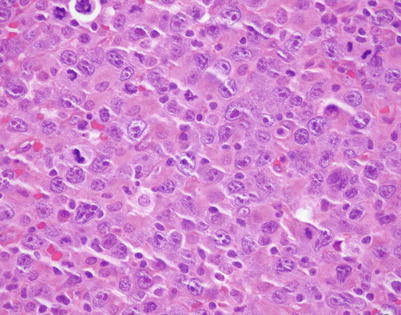

Another unusual type of large cell lymphoma that can arise in the mediastinum is the plasmablastic lymphoma, characterized by large lymphoid cells that closely resemble immunoblasts but in which the tumor cells have the immunophenotype of plasma cells. This tumor is most prevalent in HIV-positive individuals but may also be seen in other immunodeficiency states

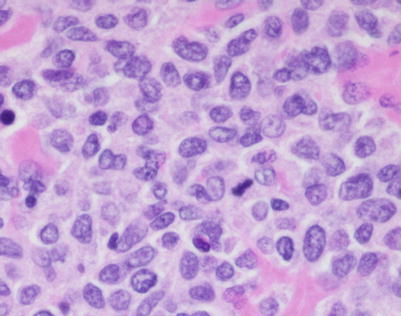

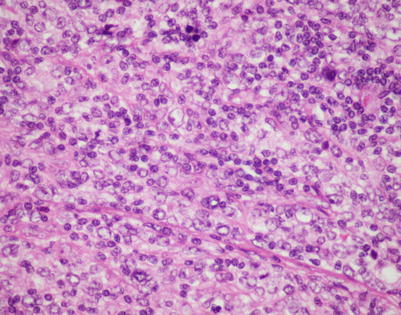

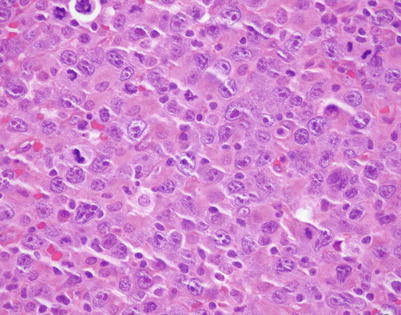

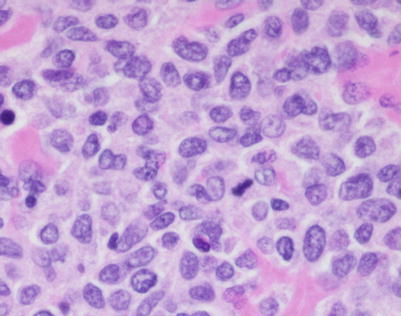

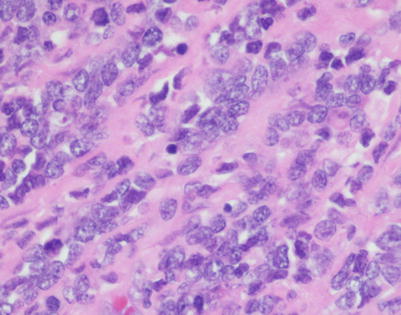

Fig. 7.38

Higher magnification of mediastinal plasmablastic lymphoma shows cells with large nuclei containing prominent (often multiple) eosinophilic nucleoli with a clumped chromatin pattern and an abundant rim of eosinophilic cytoplasm, imparting the cells with a plasmacytoid appearance. The tumors will be negative for the conventional B-cell markers but will show positivity for CD138, CD38, and MUM1. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small nuclear RNAs (EBERs) can be demonstrated by in situ hybridization in about 70 % of cases

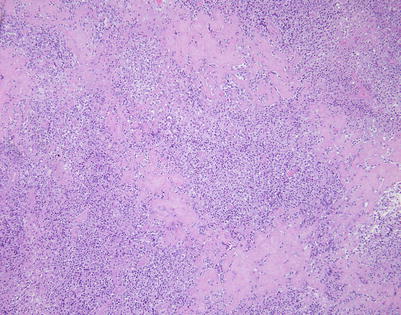

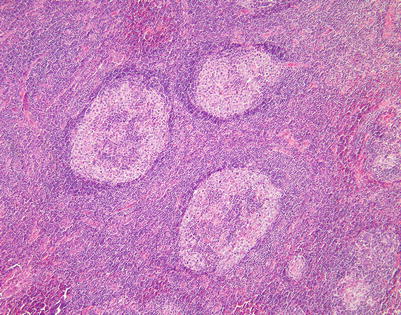

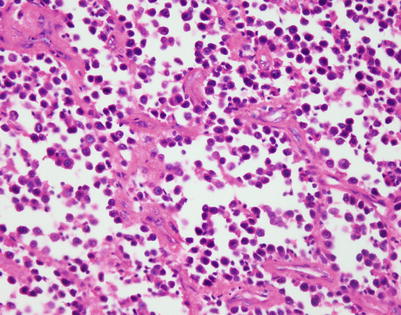

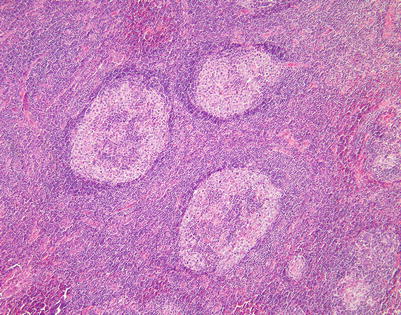

Fig. 7.39

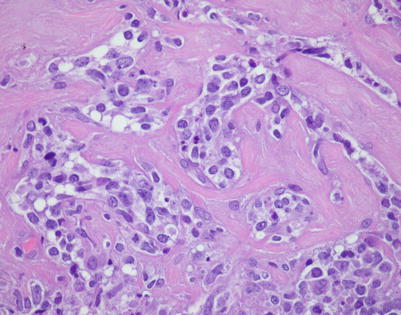

A highly unusual manifestation of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma is one characterized by marked tropism of the tumor cells for germinal centers (“germinotropic” lymphoma). The tumors are composed of sheets and small clusters of large, atypical lymphoid cells that tend to surround and encroach upon enlarged lymphoid follicles, partially or completely replacing the germinal centers

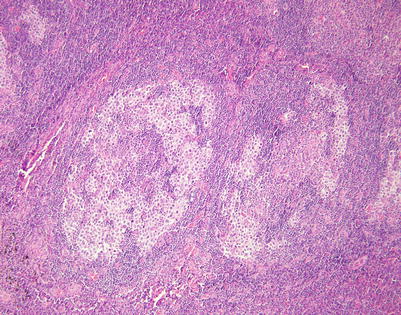

Fig. 7.40

Closer view of mediastinal DLBCL with marked tropism for germinal centers shows two enlarged lymphoid follicles with a “moth-eaten” appearance caused by the replacement of the small lymphocytes in the follicles by irregular clusters of large lymphoid cells. Notice the residual germinal center in the large follicle on the right

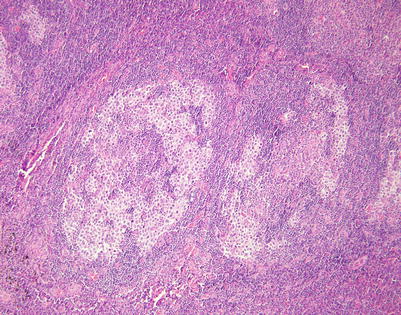

Fig. 7.41

At higher magnification, the field in Fig. 7.40 shows replacement of the large lymphoid follicle by clusters of large, atypical lymphoid cells, which are encroaching on the germinal center in the middle of the field

Fig. 7.42

Higher magnification from mediastinal DLBCL with marked tropism for germinal centers, highlighting the large, atypical lymphoid cells encroaching on the germinal center. The cells were strongly positive for B-cell markers (CD79a, CD20) and for CD45. It is important to distinguish these tumors from mediastinal seminoma, in which the tumor cells also tend to wrap around hyperplastic lymphoid follicles

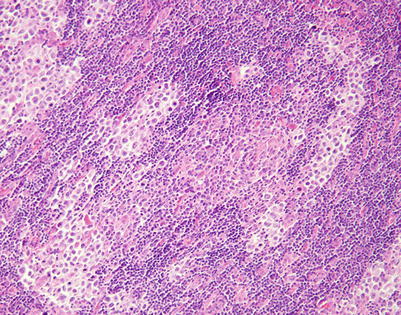

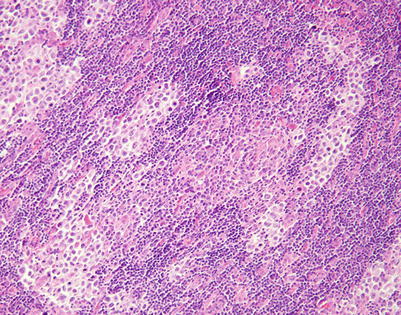

Fig. 7.43

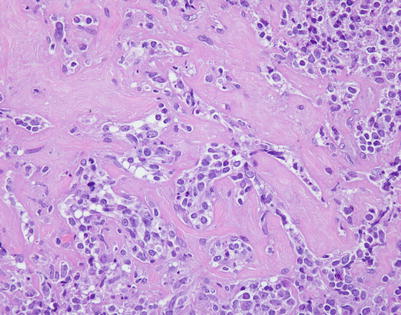

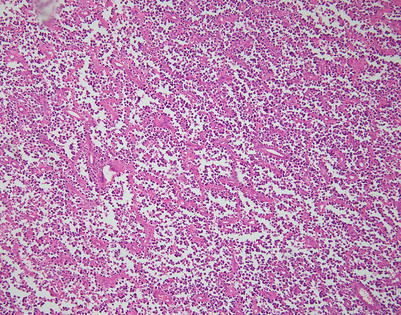

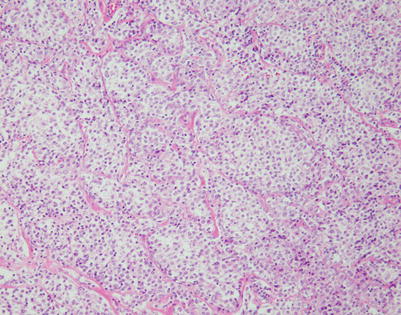

Another unusual morphologic appearance that mediastinal DLBCL can adopt is characterized by a pattern of discohesive tumor cells that seem to be breaking apart to form alveolar spaces, simulating alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

Fig. 7.44

Higher magnification of mediastinal DLBCL with an alveolar pattern shows discohesive tumor cells separated by thin strands of fibrovascular tissue. Many of the round tumor cells appear to be clinging to the lumen of the alveolar spaces; others appear to be detached and floating in the lumen

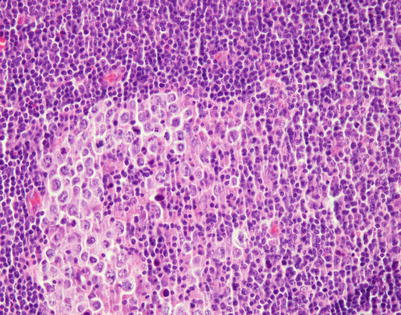

Fig. 7.45

Higher magnification from the field in Fig. 7.44 shows round tumor cells with hyperchromatic nuclei surrounded by a rim of densely eosinophilic cytoplasm reminiscent of rhabdomyoblastic cells. The tumors can be easily mistaken for a metastasis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

Fig. 7.46

Immunohistochemical stain for CD20 in mediastinal DLBCL with alveolar pattern shows strong membrane positivity of the tumor cells. Markers of myogenic differentiation (desmin, Myo-D1, myogenin) were negative in the tumor cells

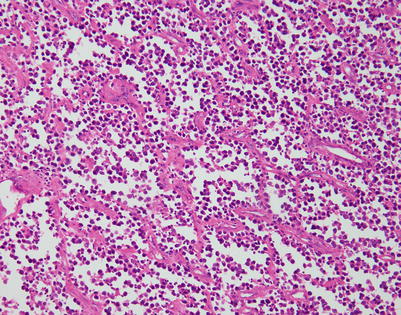

Fig. 7.47

Another example of mediastinal DLBCL with a discohesive growth pattern in which the “alveolar” spaces have become more elongated and show scattered round tumor cells, which appear to be lining or clinging to the walls of the spaces

Fig. 7.48

Higher magnification of mediastinal DLBCL with alveolar pattern, showing scattered atypical cells, some of which are clustering and forming small, abortive papillae. The tumor cells were strikingly positive for B-cell lymphoid markers and stained negative for all other differentiation markers, including myoid, epithelial, and melanocytic markers. It is important to consider lymphoma in the differential diagnosis of round blue-cell tumors in the mediastinum with a “nested” pattern

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree