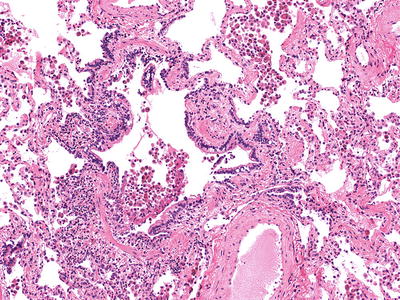

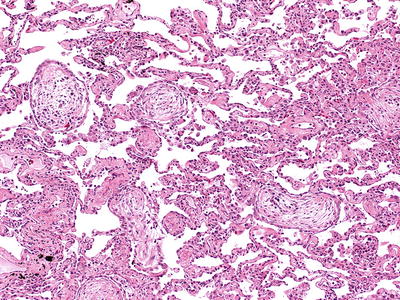

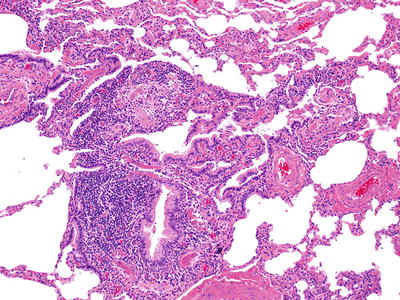

Fig. 28.1.

Intralobar seques tration. Lower segment of lobe shows end-stage changes with marked, fibrosis, and remodeled airways.

Microscopic

♦

Young patients: pathology may be normal

♦

Older patients: pathology shows chronic obstructive pneumonia; honeycomb changes are common

Extralobar

Clinical

♦

60% are found in children <1 year; 90% on left side; M:F = 4:1

♦

Frequently found with repair of diaphragmatic defect

♦

60% have other congenital anomalies such as diaphragmatic hernia and pectus excavatum (funnel chest)

Macroscopic

♦

Spongy, pyramidal mass outside of normal pleura; invested by own pleura

♦

Systemic anomalous arterial supply; venous drainage through systemic or portal systems

Microscopic

♦

May appear normal; may resemble congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM)

Bronchogenic Cysts

Clinical

♦

Supernumerary lung buds from foregut; commonly found in subcarinal or middle mediastinum location

♦

Usually incidental findings on chest imaging

Macroscopic

♦

Usually unilocular cysts with smooth margins; no communication with tracheobronchial tree

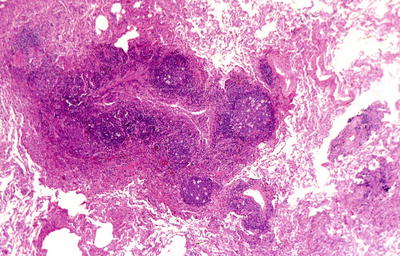

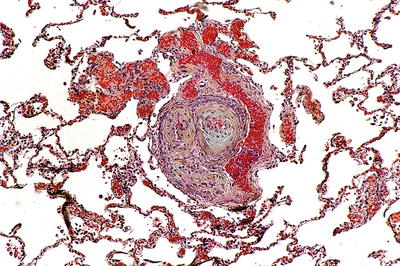

Microscopic (Fig. 28.2)

♦

Respiratory epithelium with smooth muscle, cartilage, and submucosal glands

♦

Squamous metaplasia, purulent exudate, chronic inflammation, and fibrosis if infected

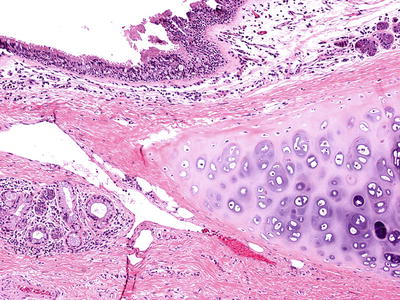

Fig. 28.2.

Bronchogenic cyst. Cyst lining contains normal ciliated respiratory epithelium submucosal glands (lower left) and hyaline cartilage, features seen in normal bronchials.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Lung abscess

Frequent bronchial communication

♦

Enteric cysts

Lined by gastric epithelium

♦

Esophageal cysts

Squamous epithelium.

Wall contains double layer of smooth muscle and no cartilage.

Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

Clinical

♦

Stillborn with anasarca and newborn with acute respiratory distress

♦

Most communicate with tracheobronchial tree

Macroscopic

♦

Five types of lesion

Type 0 – Malformation of proximal tracheobronchial tree; acinar dysplasia or dysgenesis

Type I

Most frequent type (>65% of CPAM s)

One or more large cysts; cured with surgical removal

May progress to lepidic type adenocarcinoma in older children/adults

Type II

Multiple, small, uniform cysts 0.5–2.0 cm; poor prognosis

Rhabdomyomatous dysplasia is a rare subgroup

Type III – Spongy tissue; no cysts; large bulky lesion with mediastinal shift; poor prognosis

Type IV – Large (up to 7 cm) thin-walled cystic lesions usually in periphery of lobe

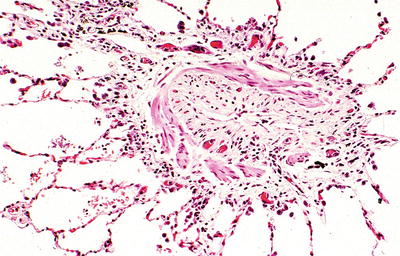

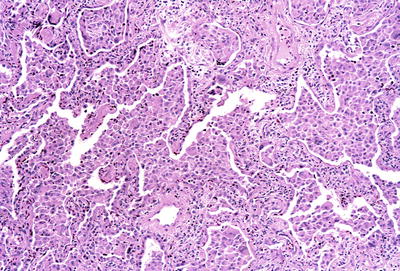

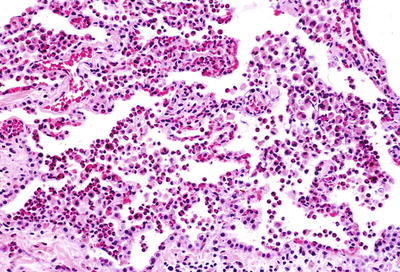

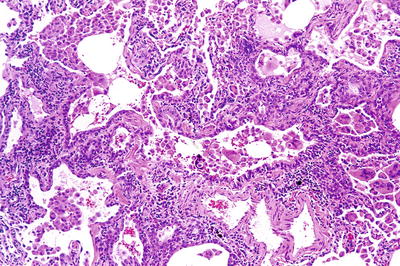

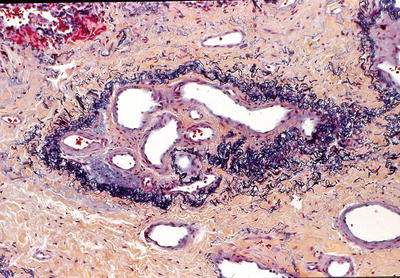

Microscopic (Fig. 28.3)

♦

Type 0 – Bronchial-like structure with respiratory epithelium, smooth muscle, and cartilaginous plates

♦

Type I – Pseudostratified, primitive epithelium; cartilaginous islands; may progress to lepidic adenocarcinoma

♦

Type II – Ciliated cuboidal or columnar epithelium

♦

Type III – Randomly distributed bronchial-like structures with ciliated cuboidal epithelium

♦

Type IV – Thinned type I and type II alveolar lining cells

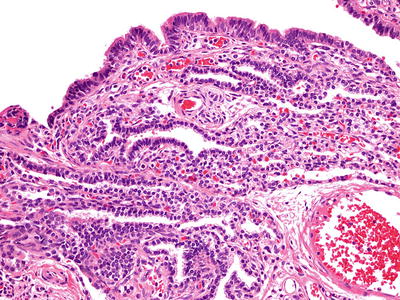

Fig. 28.3.

Type I congen ital pulmonary airway malformation. Pseudostratified respiratory-like epithelium and, in some areas, are more cuboidal epithelium line the cyst spaces. There are mixed inflammatory cells within the interstitium.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Extralobar sequestration

Located outside of pleura

Have a separate arterial blood supply

Diffuse Pulmonary Lymphangiomatosis

Clinical

♦

Occurs in young children; presents with wheezing and dyspnea; slowly progressive

♦

Sporadic

Macroscopic

♦

Firm, lobulated lung

Microscopic

♦

Proliferation of dilated, endothelial-lined spaces; may have smooth muscle in walls

♦

Expands pleura and interlobular septa

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

Occurs only in women of reproductive years

Smooth muscle is HMB45+

♦

Lymphangiectasis

Dilated channels but not increased number

Can be a component of chromosomal disorders (Turner or Down syndrome)

Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia (BPD)

Clinical

♦

Early BPD has features of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) with hypoxemia and the need for assisted ventilation for at least 28 days

♦

Established BPD causes chronic respiratory disease, with significant wheezing, and retractions and may have an associated pulmonary hypertension

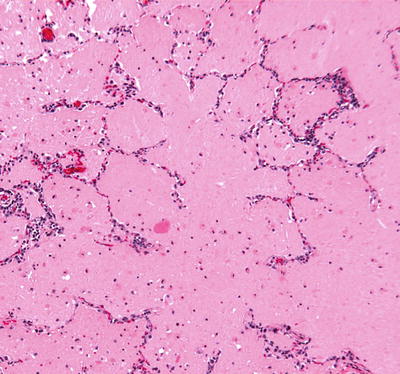

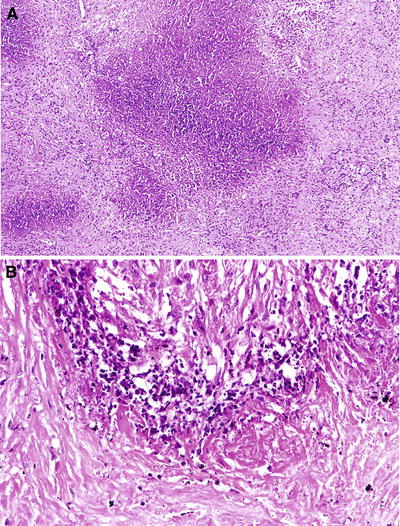

Macroscopic (Fig. 28.4A)

♦

Early BPD in nonsurfactant-treated infants resembles RDS with firm, congested, and heavy lungs

♦

Late BPD has pleural cobblestoning caused by underlying parenchymal areas that alternate between overdistension and fibrosis

Microscopic (Fig. 28.4B)

♦

Early BPD has hyaline membranes with necrotizing bronchiolitis, atelectasis, and interstitial edema

♦

Late BPD has lobules which alternate between interstitial fibrosis and distension. Lobules with distension have constrictive bronchiolitis as a sequela of the necrotizing bronchiolitis from the early BPD

Fig. 28.4.

Bronchopulm onary dysplasia (A, B). Late BPD shows a cobblestoning gross appearance (A) due to underlying alternating areas of overdistension and fibrosis (B). Courtesy of Beverly Dahms M.D., Case Western Reserve University.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Early BPD is similar to DAD

♦

Late BPD has features of emphysema, interstitial fibrosis, and constrictive bronchiolitis

Infantile (Congenital) Lobar Emphysema

Clinical

♦

Most frequent lung malformation

♦

Lobar overinflation within the first 6 months of life; presents with respiratory distress

♦

M:F = 1.8:1

Macroscopic

♦

Lung is overinflated

♦

Most commonly found in the left upper lobe

Microscopic

♦

Alveolar ducts and alveoli are distended (classic form)

♦

Absolute increase in the number of alveoli (hyperplastic form)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Congenital pulmonary airway malformation, type IV

♦

Congenital lobar inflation

Normal number of alveoli

Interstitial Pulmonary Emphysema

Clinical

♦

Occurs in two forms:

Acute interstitial pulmonary emphysema (AIPE)

Persistent interstitial pulmonary emphysema (PIPE)

♦

Found in infants over ventilated and in infants of low birth weight

♦

Incidence decreased with the use of synthetic surfactant and high-frequency oscillatory ventilation

♦

Complications include pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and pneumopericardium

Macroscopic

♦

AIPE: Spherical cysts in interstitial air spaces

♦

PIPE: Irregular and channel-like cysts in interstitial air spaces

Microscopic

♦

Air within the connective tissue and possibly the lymphatics, of the perivascular and interlobular septa

♦

Cysts formed have no lining

♦

Adjacent parenchyma may display changes of hyaline membrane disease (HMD) of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD)

♦

AIPE: No fibrosis or giant cell reaction in cyst wall

♦

PIPE: Fibrosis and giant cell reaction in cyst wall

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Pulmonary lymphangiectasis or lymphangiomatosis may mimic microscopically, but antibody D2-40 will label lymphatic endothelium and help to distinguish

Pediatric Interstitial Lung Disease

Clinical

♦

Interstitial lung disease presenting in the pediatric popular (<18 years of age) is quite rare

♦

In children <2 years of age, the term childhood interstitial lung disease in infancy (chILD) is used

♦

Causes of chILD include surfactant dysfunction mutations, including surfactant protein B and surfactant protein C, ABCA3, and TTF1 (NKX2.1) gene mutations, and storage disorders

Macroscopic

♦

Varies depending upon interstitial disease involvement; consolidation, fibrosis, and hemorrhage

Microscopic

♦

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) are most commonly seen

♦

DIP in children is not linked to smoking

♦

PAP, chronic interstitial pneumonia usually seen in surfactant gene mutation-related chILD

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Varies with the entity

Airways and Obstructive Diseases

Emphysema

Clinical

♦

Pink puffer

♦

Four major types found in four different clinical settings

Centrilobular (proximal acinar)

Smokers; upper lobes most affected

Panacinar (panlobular)

Alpha-1-protease inhibitor deficiency (ZZ); lower lobes most affected

Can be seen in talc IV drug abuse and in Ritalin use

Localized (distal acinar)

May contribute to spontaneous pneumothoraces and bullae formation in tall, asthenic male adolescent

Paracicatricial (irregular) emphysema

Most common type; around area of fibrosis

Macroscopic

♦

May manifest as bullae-alveolar spaces >1 cm or blebs-representing airspaces made by dissection through connective tissue

Microscopic

♦

Alveolar wall destruction distal to terminal bronchioles

♦

No fibrosis

♦

Four major types

Centrilobular (proximal acinar): proximal part of acini (Fig. 28.5A, B)

Fig. 28.5.

Emphysema (A, B, centrilobular; C, panacinar). Upper Fig. 28.5 (continued) lobe tissue destruction with bulla formation is characteristic of centrilobular emphysema (A). In this form, alveolar wall area destroyed in the area surrounding the bronchovascular area at the proximal and center of the respiratory lobule (B). In panacinar emphysema, tissue destruction results in a more even loss of alveolar walls throughout the lobule (C).

Panacinar: acini are uniformly involved (Fig. 28.5C)

Localized: peripheral acinar involved

Paracicatricial emphysema: emphysema adjacent to fibrosis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Congenital lobar overinflation

No destruction of alveoli

♦

Honey comb lung

Fibrosis with metaplastic columnar epithelium

Large Airway Disease

Chronic Bronchitis

Clinical

♦

“Blue bloater”

♦

Most comm on etiology is cigarette smoking

Macroscopic

♦

Excessive mucous secretion within airways

Microscopic

♦

Goblet cell hyperplasia, thickened basement membrane, submucosal gland hyperplasia, smooth muscle hypertrophy

♦

Reid index: thickness of mucous gland layer/thickness of bronchial wall (normal <0.4)

Asthma

Clinical

♦

Nonproductive cough and wheezing; atopic, nonatopic, exercise, and occupational types

♦

Affects 5% of all children; 65% of asthmatics have symptoms before age 5

♦

M:F = 2:1

Macroscopic

♦

Mucous plugging of airways; overdistention with abundant air trapping

♦

May see saccular bronchiectasis, especially upper lobe

Microscopic

♦

Thickened basement membranes; mucous plugs; goblet cell hyperplasia

♦

Submucosal gland hypertrophy; may show eosinophilic infiltrate

♦

Smooth muscle hypertrophy

♦

Curschmann spirals, Charcot–Leyden crystals, Creola bodies

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Chronic bronchitis

Histology very similar to asthma, except found only in smokers

Bronchiectasis

Clinical

♦

Causes include postinflammatory, postobstructive; seen in setting of cystic fibrosis, ciliary disorders, immunologic deficiencies, and idiopathic

♦

Recurrent pneumonias with productive cough; hemoptysis; recurrent fevers

Cystic fibrosis

Macroscopic (Fig. 28.6A)

♦

Diffuse or localized enlarged, fibrotic cartilaginous airways; dilated airways extend to pleural surface; commonly filled with mucopurulent material

Microscopic (Fig. 28.6B)

♦

Ectatic dilated airways; chronically inflamed wall; follicular bronchitis may be present

♦

Acute and organizing pneumonia is common

Fig. 28.6.

Bronchiecta sis. Diffuse airway enlargement, fibrosis, and remodeling occur in this lung with cystic fibrosis (A). The airways are irreversibly distended and surrounded by a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. The overlying respiratory epithelium many times shows a metaplastic squamous epithelium (B).

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Mucinous tumors of the airways

Malignant epithelium

Small Airway Disease

Respiratory Bronchiolitis (Smoker’s)

Clinical

♦

Incidental fin dings in smokers

Microscopic (Fig. 28.7)

♦

Pigmented macrophages within terminal bronchioles and surrounding alveoli

♦

Mild chronic inflammation, fibrosis

Fig. 28.7.

Respiratory bronchiolitis. Pigmented macrophages accumulate around a small airway with chronic remodeling changes consisting of increased smooth muscle and mild fibrosis.

Follicular Bronchiolitis

Clinical

♦

Rare small airway disease; usually associated with collagen vascular diseases, including Sjögren disease and rheumatoid arthritis, and with immunodefic iencies

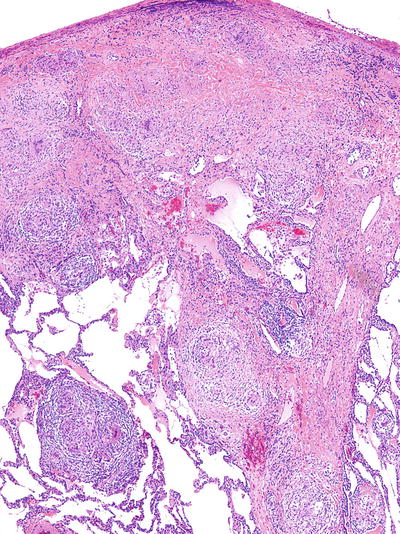

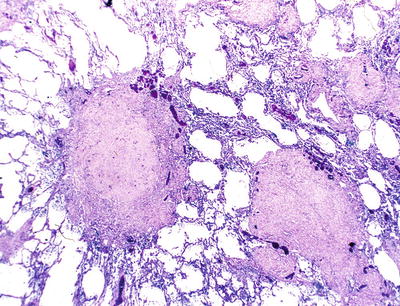

Microscopic (Fig. 28.8)

♦

Marked chronic inflammatory infiltrate surrounding small bronchioles; germinal centers are frequent; acute inflammatory cells within lumen can be seen

♦

Can be considered part of Diffuse Lymphoid Hyperplasia (see DLHP/LIP below)

Fig. 28.8.

Follicular bronchiolitis. A marked chronic inflammatory infiltrate with germinal centers surrounds small airways.

Constrictive (Obliterative) Bronchiolitis

Clinical

♦

Complication of lung or bone marrow transplantation; drug toxicity; connective tissue disease and idiopathic disease

Microscopic (Fig. 28.9)

♦

Bronchiolar and peribronchiolar fibrosis with narrowing and eventual obliteration of the lumen; may be preceded by a lymphocytic bronchiolitis

Fig. 28.9.

Constrictive (obliterative) bronchiolitis. Collagenous-type fibrosis narrows and eventually obliterates the lumen of the small airways.

Diffuse Panbronchiolitis

Clinical

♦

Seen almost exclusively in Japan; association with HLA BW54

♦

Etiology unknown; erythromycin offers some benefit

Microscopic

♦

Dense peribronchiolar infiltrate with characteristic foamy macrophages within the walls of the small bronchioles

Interstitial Diseases

Acute Lung Injury

Diffuse Alveolar Damage/Acute Interstitial Pneumonia

Clinical

♦

Pathologic correlate of adult respiratory distress syndrome; acute onset of dyspnea, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates, and rapid respiratory failure

♦

Causes include pulmonary edema, septic shock, oxygen toxicity, drugs (including chemotherapeutics), radiation, and trauma

♦

Idiopathic variant is known as acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP ) – Hamman–Rich syndrome

Macroscopic

♦

“Respirator lung”-dense, red/gray diffuse consolidation

Microscopic (Fig. 28.10A, B)

♦

Temporally uniform injury

♦

Two phases: acute and organizing

Acute: interstitial edema, type I pneumocyte sloughing and hyaline membranes.

Organizing: proliferating type II pneumocytes and interstitial fibroblasts with focal airspace organization.

Bronchiolar epithelial necrosis, reepithelialization and organization within airways.

Acute and organizing thrombi within vessels are common

Fig. 28.10.

Acute and org anizing diffuse alveolar damage. Hyaline membranes in the alveolar spaces (A) and are eventually organized into and widen the interstitium (B).

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Organizing pneumonia including cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP)/bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP)

More subacute clinical course.

Process is patchy around bronchioles.

Hyaline membrane s are not seen.

Organization is intraluminal.

Organizing Pneumonia (COP)/Bronchiolitis Obliterans Organizing Pneumonia (BOOP)

Clinical

♦

A general term found in three clinical scenarios: postinfection repair process, systemic diseases such as collagen vascular disease (bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP )), and idiopathic (cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP ) )

♦

Subacute onset of cough, dyspnea, and fever; multiple patchy airspace opacities, usually bilateral, on chest imaging

♦

Treated with steroids; excellent prognosis

Microscopic (Fig. 28.11)

♦

Temporally uniform injury

♦

Patchy, immature fibroblastic proliferations within bronchiolar lumina and peribronchiolar airspaces; usually sharply demarcated with adjacent normal parenchyma

♦

Foamy macrophages are commonly found in airspaces surrounding fibrosis

♦

Interstitial chronic inflammation and type II pneumocyte hyperplasia in area of fibrosis

Fig. 28.11.

Cryptogenic or ganizing pneumonia (COP)/bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP). Organizing fibrosis in the form of fibroblastic proliferation is present within the bronchiolar and alveolar airspaces. The adjacent alveolar walls are relatively unremarkable.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Diffuse alveolar damage/acute interstitial pneumonia

More acute clinical course.

More diffuse process, involving both bronchioles and alveoli.

Organizing fibrosis is interstitial

♦

Usual interstitial pneumonia

Temporally heterogeneous injury.

Interstitial fibrosis is predominantly subpleural and paraseptal with scattered fibroblastic foci.

Collagen deposition honeycomb foci can be found.

Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

Respiratory Bronchiolitis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease (RB-ILD)

Clinical

♦

Smokers’ disease

♦

Dyspnea, cough, mild restrictive defects

♦

Chest imaging usually normal; may present as interstitial infiltrates

Microscopic

♦

Finely granular-pigmented macrophages accumulate within lumens of distal bronchioles and surr ounding alveoli

♦

Mild chronic inflammation and fibrosis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Desquam ative interstitial pneumonia

Mild interstitial fibrosis

♦

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH)

Characteristic nodules with Langerhans cells (S-100 protein+, CD1a+)

Peribronchiolar-based Langerhans cells

Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonitis (DIP)

Clinical

♦

Usually in middle-aged adults, 90% are smokers; insidious onset of dyspnea

♦

Chest imaging: bilateral, lower lobe, ground-glass opacities

♦

Favorable response to corticosteroids

♦

Mean survival = 12 years

Microscopic (Fig. 28.12)

♦

Striking pigmented macrophages within alveolar spaces; type II pneumocyte hyperplasia with subtle interstitial fibrosis

♦

Diffuse process; temporally uniform

Fig. 28.12.

Desquamative i nterstitial pneumonitis. Abundant pigmented macrophages fill the alveolar spaces. Reactive type II pneumocytes line the alveolar walls.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

DIP-like reaction of UIP

Temporally heterogeneous pattern of injury

♦

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH)

Patchy distribution; predominantly bronchiolar

Tightly packed macrophages (Langerhans cells)

Can be found in patients <40 years old

♦

Respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease

No interstitial fibrosis

Less mac rophage accumulation and more airway centered

Usual Interstitial Pneumonitis

Clinical

♦

Insidious onset of dyspnea with chronic, progressive downhill course

♦

Most patients are 40–70 years old; collagen vascular diseases are commonly present

♦

60% of patients die; mean survival 3 years

Microscopic (Fig. 28.13 B, C)

♦

Temporally heterogeneous pattern of injury; “variegated” low-power appearance; fibrosis worse in subpleural and paraseptal regions

♦

Infiltrate is chronic with plasma cells; germinal centers commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis

♦

Most fibrosis is dense collagen; intervening fibromyxoid foci are seen; large, ectatic airspaces with mucin pooling usually found in more advanced areas; areas of normal lung present centrally in lobule

♦

Smooth muscle hypertrophy and DIP-like reaction around bronchioles are common

♦

Vascular changes of intimal fibroplasia and medial hypertrophy are common

Fig. 28.13.

Usual interstitial pne umonia with honeycomb changes (A, B) and fibroblastic foci (C). Honeycomb airspaces filled with mucous are present in the base of the lobe (A). The chronic inflammation and fibrosis in this pattern of injury have a variegated low-power appearance (B) with characteristic fibroblastic foci intervening between the normal and the fibrotic areas of the lung (C).

Differential Diagnosis

♦

DIP

Macrophage accumulation is diffused.

Injury is temporally uniform

♦

COP/BOOP

Injury is temporally uniform

Clinical course is subacute

Fibroblastic foci are more pronounced

Areas of dense collagen deposition are absent

♦

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia/fibrosis (NSIP)

Injury is temporally uniform

Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia/Fibrosis

Clinical

♦

Dyspnea and cough over several months; bilateral interstitial infiltrates on chest imaging

♦

Middle-aged adults; underlying connective tissue disease is common; idiopathic

♦

Cellular form is usually steroid responsive with good prognosis

♦

Fibrotic form may act similar to UIP

Microscopic (Fig. 28.14)

♦

Two types

Cellular

Interstitial chronic inflammation with lymphocytes and plasma cells

Preserved lung architecture

Fibrosing

Patchy or diffuse temporally uniform interstitial fibrosis

Fig. 28.14.

Nonspecific interst itial pneumonia. A chronic, lymphocytic infiltrate is present in the alveolar walls, and the overall lung architecture is preserved in this cellular type of NSIP.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Usual interstitial pneumonia

Injury is temporally heterogeneous with fibroblastic foci

Collagen deposition and honeycomb changes are seen

Diffuse Lymphoid hyperplasia/Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia here

Extrinsic Allergic Alveolitis (Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis)

Clinical

♦

Insidious onset of dyspnea with dry cough, fatigue, and malaise

♦

Exposure source not identified in 67% of cases diagnosed by pathology; diffuse interstitial infiltrates on chest X-ray

♦

Corticosteroids help after exposure has been eliminated

Microscopic (Fig. 28.15)

♦

Triad of features: interstitial pneumonitis; chronic bronchiolitis with areas of organizing pneumonia and ill-formed, nonnecrotizing granulomas or giant cells in parenchyma

Fig. 28.15.

Extrinsic alle rgic alveolitis/hypersensitivity pneumonitis. A prominent cellular bronchiolitis along with an interstitial pneumonitis is a major component.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Usual interstitial pneumonia

Injury is temporally heterogeneous.

Granulomas usually not seen

♦

Sarcoidosis

Interstitial pneumonia, if present, is very mild.

Granulomas are well formed in lymphatic distribution

♦

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia

Pathology is more diffusely distributed.

Does not have areas of organizing pneumonia.

Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Clinical

♦

Four clinical categories:

Simple: Loeffler syndrome; mild; self-limiting

Tropical: found in tropics due to filarial infestation

Acute: acute, febrile illness with respiratory failure; unknown etiology

Chronic: subacute illness; blood eosinophilia; F > M; patchy, peripheral infiltrate (photographic negative of pulmonary edema); etiologic agents (drugs, fungal, parasites, inhalants, and idiopathic)

Microscopic (Fig. 28.16)

♦

Filling of alveolar spaces with eosinophils and variable number of macrophages

♦

Eosinophilic abscesses and necrosis of cellular infiltrate; organizing pneumonia is common

♦

Features of DAD have been seen in acute form; mild, nonnecrotizing vasculitis of small arterioles and venules common

Fig. 28.16.

Eosinophilic pn eumonia. There are abundance eosinophils with scattered alveolar macrophages that fill the alveolar spaces.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Churg– Strauss syndrome

Necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis is present

♦

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH)

Infiltrate is interstitial and usually peribronchiolar.

Seen only in smokers

♦

Desquamative interstitial pneumonitis

Eosinophilic abscesses and necrosis of infiltrate rarely seen

Vasculitis not seen

Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Clinical

♦

Occurs almost exclusively in smokers; M:F = 4:1; symptoms may be minimal; fourth decade

♦

Chest imaging: multiple, bilateral nodules 0.5–1.0 cm in upper lung lobes with cystic lesions

Microscopic (Fig. 28.17A, B)

♦

Discrete, nodular/stellate lesions; bronchiolocentric

♦

Langerhans cell: convoluted (kidney-bean) nuclei

Fig. 28.17.

Pulmonary Lang erhans cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma). The cellular phase of this disease shows prominent bronchiolocentric inflammation that has a somewhat stellate shape (A); histiocytes with a kidney-bean-type appearance are present (B).

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Langerhans cells: S100+, CDla+, HLR-DR+

Electron Microscopy

♦

Birbeck granule (“tennis racket” morphology)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

DIP

Inter stitial lesion

♦

Respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease

Does not destroy bronchiole

Minimal fibrosis

No Langerhans cells

Sarcoidosis

Clinical

♦

Most common in young, African-American female (20–35 years old)

♦

Deficient T-cell response (cutaneous T-cell anergy and decreased helper T cells)

♦

Associations: functional hypoparathyroidism; hypercalciuria ± hypercalcemia; erythema nodosum; uveitis

♦

Kveim test: granulomatous reaction following injection of human spleen extract

♦

Serum ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme)

♦

Radiologic stage

Stage 0: Normal chest X-ray

Stage 1: Hilar/mediastinal adenopathy

Stage 2: Hilar/mediastinal adenopathy + interstitial pulmonary infiltrate

Stage 3: Interstitial pulmonary infiltrate only

Stage 4: End-stage fibrosis with honeycombing

Microscopic (Fig. 28.18)

♦

Interstitial noncaseating granulomata distributed in lymphatic and bronchovascular pathways; vascular and pleural involvement common

Fig. 28.18.

Sarcoidosis. Predom inantly nonnecrotizing granulomas with giant cells follow the subpleural and interlobular septa in a lymphatic type distribution.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Chronic berylliosis

Elevated beryllium levels on tissue quantitation

Clinical history of beryllium exposure

♦

Extrinsic allergic alveolitis

Ill-formed granulomata; interstitial distribution

Accompanying interstitial pneumonia

Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis

Clinical

♦

Etiologies: dusts, drug, immunodeficiency, leukemia, kaolin

♦

Bronchoalveolar lavage: treatment of choice

♦

Idiopathic or associated with infection

♦

Anti-GM-CSF circulating antibody found in idiopathic variant

Microscopic Features (Fig. 28.19)

♦

Accumu lation of granular eosinophilic material in alveoli; PAS+ material

Fig. 28.19.

Pulmonary alveolar pro teinosis. An eosinophilic material fills the alveolar spaces; the alveolar walls are essentially unremarkable.

Electron Microscopy

♦

Lamel lar body

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Pulmonary edema

Interstitial/septal edema

♦

Mycobacterial, nocardial, or Pneumocystis pneumonia

Positive special stains or microbiologic cultures

Anti-Basement Membrane Antibody [ABMA] Disease (Goodpasture syndrome)

Clinical

♦

M: F = 9:1; bimodal distribution of presentation (peaks at 30 and 60 years)

♦

Smokers; DRw15, DQw6

♦

Cytotoxic, antibody-mediated, immune reaction; antibodies to type IV collagen in serum cross-react to both kidney and lung

♦

Hemoptysis, anemia, azotemia, and diffuse lung infiltrates

Microscopic

♦

Extensive intra-alveolar hemorrhage; nonspecific type II pneumocyte hyperplasia

♦

Small vessel vasculitis may be present

♦

Iron encrustation of elastic fibers within interstitium and vessels may be present

♦

Mild interstitial fibrosis can be seen

Immunofluorescence:

♦

Linear staining of glomerular and pulmonary basement membranes for IgG

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other causes of small vessel vasculitis

Absence of ABMA in tissue by immunofluorescence

♦

Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis

Child and adolescent.

Immunofluorescent linear pattern is absent.

No acute hemorrhage.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Hemosiderosis

Clinical

♦

Exclusively in children <16 years; M:F = 1:1

♦

Hemoptysis, hypoxemia, chest infiltrates; iron deficiency anemia

♦

Stachybotrys chartarum may be an etiologic agent

♦

Poor prognosis with death in majority at 2–5 years

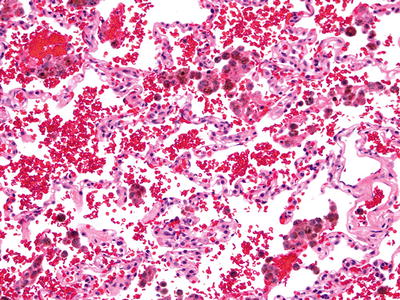

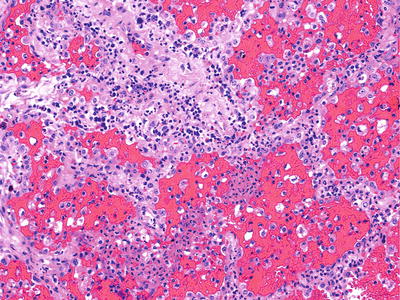

Microscopic (Fig. 28.20)

♦

Intra-alveolar hemorrhage without capillaritis; alveolar wall thickening and type II pneumocyte hyperplasia

♦

Bronchoalveolar lavage with hemosiderin-laden macrophages in large numbers

Fig. 28.20.

Idiopathic pu lmonary hemosiderosis. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages are abundant adjacent to mildly thickened alveolar septa with type II pneumocytes.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

ABMA Disease

Linear immunofluorescence pattern (IgG)

Kidney involvement

Pneumoconioses

♦

A n onneoplastic reaction of the lungs to inhaled mineral or organic dust

Silicosis

Clinical

♦

Reaction in lung to inhaled crystalline silica: stonecutting, quarry work, or sandblasting

♦

0.5–2 micron fibers: most fibrogenic

♦

Predisposed toward tuberculosis (TB)

Macroscopic

♦

Firm, discrete, rounded lesions with variable amounts of black pigment

♦

Nodules in lymphatic distribution: around bronchovascular bundles, in subpleural and interseptal areas

Microscopic (Fig. 28.21)

♦

Discrete foci of concentric layers of hyalinized collagen; dust-filled histiocytes are abundant; birefringent particles usually present

♦

When necrosis is present, consider complicating infection by mycobacterial tuberculosis

Fig. 28.21.

Silicotic n odule. Multiple hyalinized nodules are adjacent to bronchioles.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Inactive mycobacterial or fungal infections

Giant cells and palisading histiocytes are usually seen

♦

Hyalinizing pulmonary granuloma

Collagen bundles are disorganized.

Birefringent material is unusual.

Asbestos-Related Reactions

Clinical

♦

Reactions of the lung to asbestos with accompanying cations (i.e., iron, calcium, magnesium, sodium); serpentine and amphibole are the most common types

♦

Fibrosis occurs 15–20 years after exposure and can progress after exposure stops

Macroscopic

♦

Firm, fibrotic lungs with areas of honeycomb change

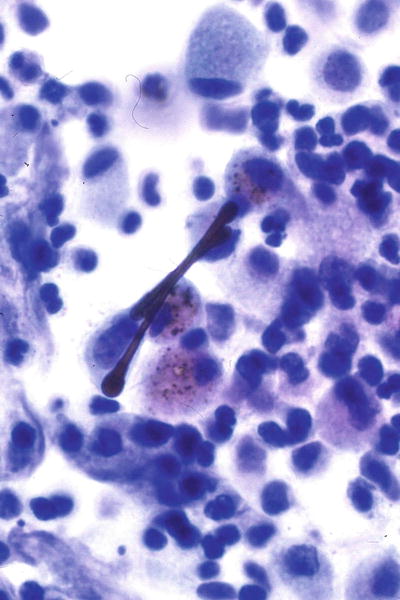

Microscopic (Fig. 28.22)

♦

Marked interstitial fibrosis with minimal inflammatory infiltrate; UIP-like reactions common

♦

Presence of asbestos bodies, fibrosis, and exposure history is needed for definitive diagnosis

♦

Hyalinizing pleural plaques, pleural fibrosis, and rounded atelectasis can also be seen

Fig. 28.22.

Asbestos-r elated reactions – ferruginous body. Asbestos fiber within the core surrounded by a proteinaceous iron-containing coat takes on a dumbbell shape.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Usual interstitial pneumonia

Temporally heterogeneous

Lack of asbestos bodies

Coal Worker’s Pneumoconiosis (CWP)

Clinical

♦

Simple: single nodule, <2 cm

♦

Complicated: >2 cm, including progressive massive fibrosis

♦

Caplan syndrome: rheumatoid nodule with CWP (progressive massive fibrosis)

Microscopic (Fig. 28.23B)

♦

Hyalinized nodule with anthracotic pigment in lung and lymph nodes

♦

Macules adjacent to bronchioles; may have centrilobular emphysema

Fig. 28.23.

Progressive ma ssive fibrosis/coal worker’s pneumoconiosis. Black/tan mass involves majority of the upper lobe (A); hyalinized nodule adjacent to the airway with emphysema (B).

Hard Metal Pneumoconiosis

Clinical

♦

Exposure to tungsten carbide and cobalt, usually in grinding, drilling, cutting, or sharpening

♦

Dyspnea with restrictive pulmonary function tests

Microscopic (Fig. 28.24)

♦

Giant cell interstitial pneumonitis with interstitial fibrosis, peribronchiolar giant cells, and DIP-like reaction

♦

Giant cells are multinucleated and commonly engulf other inflammatory cells

Fig. 28.24.

Hard metal pneumoconio sis/giant cell pneumonitis. Peribronchiolar infiltrate with macrophages and scattered giant cells and prominent smooth muscle is seen in small airways.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Viral bronchiolitis/pneumonitis

No history of tungsten carbide/cobalt exposure

♦

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

Increased interstitial and peribronchiolar inflammatory infiltrate

Nonnecrotizing granulomas

Berylliosis

Clinical

♦

Acute: Massive exposures produce acute respiratory distress syndrome-like pictures

♦

Chronic: Progressive dyspnea and cough with imaging studies similar to sarcoidosis; may progress to interstitial fibrosis

Macroscopic

♦

Nodules (up to 2 cm) with associated emphysema

Microscopic

♦

Nonn ecrotizing granulomas in a lymphatic distribution

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Sarcoidosis

No history of beryllium exposure

♦

Infections (mycobacterial or fungal)

Necrotizing granulomas

More airway distribution

Vascular Conditions

Vasculitides (Also See Chapter XX)

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA)

Clinical

♦

Triad: upper airway, lower airway (lung), and kidney; saddle nose; rarely lung only (so-called limited)

♦

40% of patients in remission are c-ANCA+ (anti-proteinase 3); 90% of patients with active disease are c-ANCA+

♦

Chest imaging: multiple well-demarcated peripheral nodules, lower lobes; rarely as a solitary pulmonary lobule

Microscopic (Fig. 28.25)

♦

Triad: parenchymal (basophilic) necrosis, vasculitis, granulomatous inflammation

♦

Variants: eosinophil-rich, bronchiolocentric, solitary, capillaritis, and diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage

♦

Parenchymal necrosis may be in form of microabscesses or geographic necrosis

♦

Vasculitis may affect arteries, veins, or capillaries

Fig. 28.25.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis. (A) Geographic necrosis. (B) Collagenous necrosis. A large area of basophilic necrosis (A) is lined by histiocytes and scattered giant cells (B).

Differential Diagnosis (Table 28.1)

♦

Lympho matoid granulomatosis

Atypical cytology

♦

Granulomatous infections

Well-formed, nonnecrotizing granulomas

Eosinophilic necrosis

♦

Rheumatoid nodules

Found only in the setting of clinical rheumatoid arthritis

Usually subpleural

♦

Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis

Well-formed nonnecrotizing granulomas in lymphatic distribution in lung adjacent to necrobiotic nodule

Table 28.1.

Diffe rential Diagnosis of Granulomatous Lesions

NSG | GPA | Infection | Churg–Strauss syndrome | Rheumatoid nodule | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sarcoidal granuloma | ++ | − | ++ | + | − |

Vasculitis | ++ | ++ | +/− | ++ | − |

Necrosis | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

Hilar adenopathy | +/− | − | ++ | − | − |

Cavitation | + | ++ | + | ++ | + |

Asthma/peripheral eosinophilia | − | − | − | + | − |

Tissue organismal stains (fungal/mycobacterial) | − | − | + | − | − |

Churg–Strauss Syndrome (Allergic Angiitis Granulomatosis)

Clinical

♦

Asthma, eosinophilia, systemic vasculitis, mono- or polyneuropathy

♦

Nonfixed lung infiltrate, paranasal sinus abnormalities; p-ANCA+

Microscopic

♦

Eosinophilic infiltrates, granulomatous inflammation, and necrotizing vasculitis

Differential Diagnosis (Table 28.1)

♦

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia

Nongranulomatous

♦

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

Bronchocentric

♦

Drug- induced vasculitis

♦

Polyarteritis nodosa

Rarely involves the lung

♦

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Geographic necrosis

Necrotizing Sarcoid Granulomatosis (NSG)

Clinical

♦

F:M = 2.2:1; variable age presentation; cough, chest pain, weight loss, fever

♦

No systemic vasculitis

♦

Chest imaging: bilateral lung nodules, usually lower lobe; hilar adenopathy is present in <10% of cases

Microscopic

♦

Lymphoplasmacytic or granulomatous vasculitis; parenchymal necrosis without necrotizing vasculitis; numerous caseating sarcoid-like granulomas

Differential Diagnosis (Table 28.1)

♦

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA)

No sarcoidal granulomas

♦

Infection:

Vasculitis not a prominent component

Positive organismal stains

♦

Churg–Strauss syndrome (allergic angiitis granulomatosis)

No hilar adenopathy

History of asthma

Peripheral eosinophilia

Necrotizing Capillaritis

Clinical

♦

Associated conditions: collagen vascular disease, especially systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener granulomatosis, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, cryoglobulinemia, Behçet disease, drug reactions (sulfonamides), and Goodpasture disease

Microscopic (Fig. 28.26)

♦

Focal necrosis of alveolar septa with neutrophilic infiltration, capillary fibrin thrombi, and interstitial hemorrhage/hemosiderosis

♦

Often associated with foci of DAD

Fig. 28.26.

Necrotizing capill aritis. A neutrophilic infiltrate involves the alveolar septa capillaries.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Acute hemorrhagic bronchopneumonia

Neutrophils predominate in alveolar space

Pulmonary Hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension (PH)

Clinical

♦

Idio pathic pulmonary hypertension

F:M 1.7:1

♦

Familial (FPAH)

Germline mutations in BMPR2 (chromosome 2q31-32)

♦

Associated with:

Collagen vascular disease

Congenital cardiac shunts

Portal hypertension

HIV infection

Drugs and toxins

Aminorex fumarate

Microscopic (Fig. 28.27)

♦

Path ologic changes from low grade to high grade

Muscularization of pulmonary arteries

Cellular intimal proliferation

Intimal concentric laminar fibrosis

Plexiform lesions

Plexiform and angiomatoid lesions

Necrotizing arteritis

Fig. 28.27.

Pulmonary hyperte nsion – plexogenic arteriopathy. A plexogenic lesion contains a remodeled artery wall with abnormal vascular spaces lined by myofibroblasts.

Pulmonary Veno-Occlusive Disease with Secondary Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

Clinical

♦

Rare form of pulmonary hypertension; 33% occur in children

♦

Causes: drug toxicity, especially chemotherapeutics, viral infections

Microscopic (Fig. 28.28)

♦

Congestive changes with hemosiderin-laden macrophages

♦

Pulmonary hypertensive changes

♦

Intimal fibrosis and thrombosis of veins; recanalization is common

Fig. 28.28.

Pulmonary veno-occ lusive disease (PVOD). A vein containing prominent intimal fibrosis and recanalization (colander lesion) is characteristically found in this disease.

Pulmonary Capillary Hemangiomatosis

Clinical

♦

Rare cause of pulmonary hypertension; most patients between 20 and 40 years old

Microscopic

♦

Abnormal proliferation of capillary-like vessels in alveolar septa; patchy hemosiderin

♦

May have secondary venous changes with intimal fibrosis

Thrombotic Arteriopathy

Clinical

♦

Sudden shortness of breath with pleuritic pain

Macroscopic (Fig. 28.29)

♦

Hemorrhagic wedge-shaped peripheral lesions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree